USS Nevada was the only battleship to get underway during the attack at Pearl Harbor. The recent discovery of the ship's hull revived interest in her dramatic story.

-

Winter 2021

Volume66Issue1

Editor's Note: After serving in the Navy during Vietnam, Ed Offley reported on Naval issues for three decades for The Ledger-Star in Norfolk and The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and was Editor-in-Chief of Stars & Stripes. He has written five books, including a favorite of ours, Scorpion Down: Sunk by the Soviets, Buried by the Pentagon. We are delighted to publish a two-part report on the dramatic history of the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36), which survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and went on to serve in the Aleutians, Atlantic convoy escort duty, the Allied liberation of Normandy and southern France, and the climactic battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. The second part of the essay is "Revenge of the Nevada" in the June 2021 American Heritage.

On May 11 this year, an unmanned submersible slowly plied its way along the Pacific seabed nearly three miles below the surface of the ocean, hunting its prey. The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) carried a video camera and lights to illuminate a target if found.

For several weeks the search had been underway for the World War II battleship USS Nevada (BB-36), lost in the depths for more than seven decades. Suddenly fragments of a large ship appeared on digital screens in the control room of the mother ship Pacific Constructor high up on the surface: an immense hull resting upside down on the seabed; its bow section close by, with teak planking and an anchor chain clearly visible; further on rested another hull fragment.

The ROV continued its search, soon edging around the third major section. There, painted in white and still clearly visible, hull number 36 came into clear view. The Nevada had been found. But that discovery was not the search team’s only accomplishment.

In announcing the sighting of the warship, scientists and engineers from the marine robotics firm Ocean Infinity and its partner, the underwater archeological firm SEARCH Inc., also resurrected a forgotten chapter in American naval history: the long saga in peace and war of the USS Nevada. It is a story that began at the turn of the 20th century, spanned two world wars, and culminated at the dawn of the nuclear age. The ship’s rich history deserves attention, especially the unprecedented, heroic action of its crew on the U.S. Navy’s darkest day.

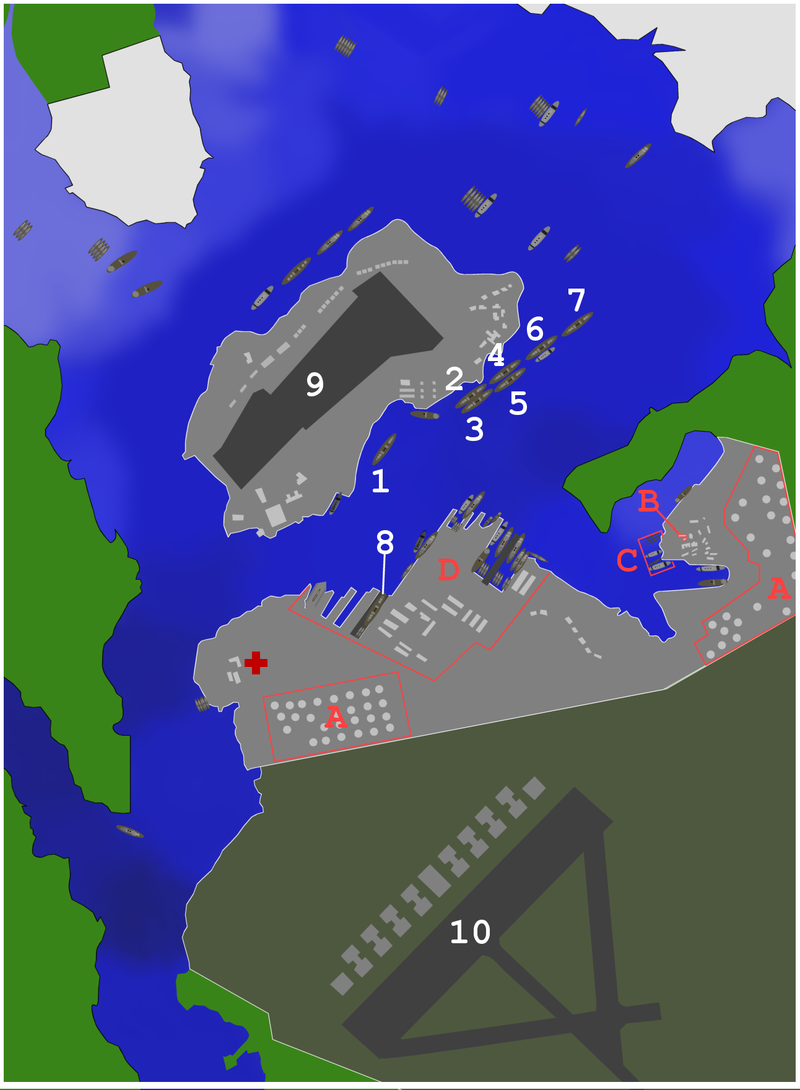

DECEMBER 7, 1941. In the last moments of peace, the crowded naval anchorage at Oahu was quiet and calm. A gentle breeze wafted in from the northeast as the sun rose above Mount Tantalus and the rest of the Ko’olau range that forms the island’s geological spine. The piers and mooring quays at Pearl Harbor were filled with over seventy warships of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, including eight battleships, eight cruisers and thirty destroyers, as well as several dozen auxiliaries.

The only major warships missing were the fleet’s three aircraft carriers: USS Enterprise (CV-6) and its cruiser and destroyer escorts had left Pearl Harbor on November 28 to deliver extra aircraft to the Marines on Wake Island; seven days later, USS Lexington (CV-2) with its escorts left to deliver aircraft to Midway Island. The third carrier, USS Saratoga (CV-3), was in San Diego for prescheduled maintenance.

Normally, half the battleships would be at sea while the others were in port, but because the two carriers had opted for speed as they steamed for Midway and Wake, they had left the slower battleships behind. Thus, Nevada, USS Arizona (BB-39) and USS Oklahoma (BB-37) on December 5 had detached from the Lexington task force to join the rest of the fleet in Pearl Harbor.

Anchored at Berth F-8 just beyond the far northern end of Ford Island, Nevada’s sailors had an unobstructed view looking down Battleship Row, where six more of the fleet’s battlewagons and fleet oiler USS Neosho (AO-23) were moored. The repair ship USS Vestal (AR-4) was tied alongside Arizona at the next quay, Berth F-7, followed by four battleships moored in two pairs – USS Tennessee (BB-43) and USS West Virginia (BB-48) at Berth F-6, and Maryland (BB-46) and Oklahoma at F-5. Then came fleet oiler Neosho at F-4, followed by USS California (BB-44) at the westernmost quay in use, Berth F-3. Further down and on the other side of the main channel, two dozen other ships were tied up to the piers or in drydock at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard, including the eighth battleship, USS Pennsylvania (BB-38). Another 40 destroyers and auxiliaries were anchored in the lochs to the north and west of Ford Island.

No one aboard ship that morning could have realized that this scene of tranquility was about to erupt into an inferno of chaos, destruction and death. Less than two hours later, the Nevada – led by a reserve lieutenant commander, and aided by a handful of young ensigns and a skeleton crew – would be steaming down the channel past Ford Island through choking clouds of burning bunker oil as the rest of the Pacific battleship force burned, while dozens of enemy dive bombers swarmed down in attack; nor that their desperate race for the open sea would become a legend of courage under fire, and a rare ray of good news amid the catastrophe of the Japanese attack.

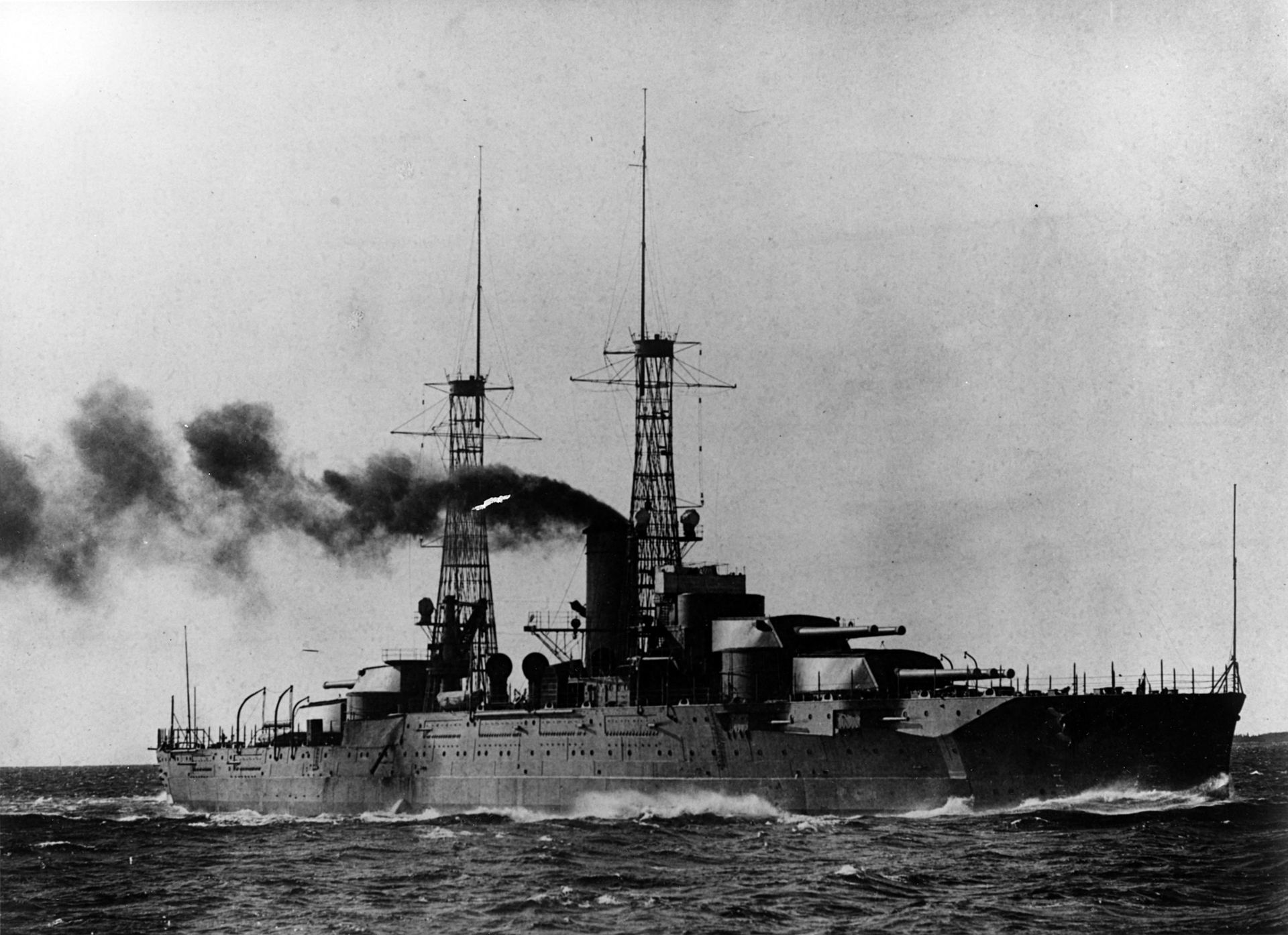

IN EARLY December 1941, the Nevada was one of seventeen operational battleships in the U.S. Navy, and in her twenty-fifth year of service. She was the fourth oldest operational battleship, and the oldest present at Pearl Harbor. Laid down on November 4, 1912 at the Fore River Shipbuilding Co. shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts, upon her commissioning in 1916 Nevada was lauded as the most powerful warship in the world. She was also at that point the endgame result of a worldwide naval arms race that began long before the young sailors who first manned its rails that year had been born.

With the advent in the 1880s of steel-hulled warships propelled by steam and brandishing naval guns firing explosive shells, the major naval powers fell into a relentless competition to build battleships that would out-perform adversaries and allies alike. During the twenty-year span between 1894 and 1914, the U.S. Navy constructed and operated thirty-seven coal-fired battleships comprising three distinct generations of naval technology. This began with the relatively primitive USS Texas and her doomed sister ship USS Maine (which triggered the Spanish-American War when she exploded and sank in Havana harbor). Initially designated as “armored cruisers,” the two ships were later reclassified as “coastal battleships.” The U.S. Navy’s victories in Manila Bay and at Santiago de Cuba were possible because the obsolete, aging Spanish squadrons were even less capable than the American navy, which had commissioned four 10,000-ton Indiana-class battleships prior to the outbreak of hostilities.

During the eight years after the Spanish surrender, American shipyards produced fourteen new battleships comprising a second generation of naval technology. In armament alone, the new ships were clearly superior.

While the doomed Maine had a pair of 12”/35-cal. main guns that fired a 510-pound shell a maximum of 12,000 yards (under six nautical miles), the later battleships sported four 12”/45-cal. guns in a pair of twin turrets that could shoot an 870-pound armor-piercing shell out to a maximum range of 20,000 yards (nearly ten nautical miles). The newer battleships were also designed for open ocean operations, with a maximum cruising range of 5,000 nautical miles, a 33-percent increase over the first-generation coastal battleships. Yet when President Theodore Roosevelt dispatched eighteen of these warships on an extended, around-the-world cruise as “The Great White Fleet,” they too had already been rendered obsolete. The British in 1906 had commissioned a battleship whose capabilities dwarfed those of all other navies.

HMS Dreadnought was a massive 18,000-ton battleship armed with ten 12”/45-cal. main guns that fired an 850-pound armor-piercing shell out 25,000 yards. The first battleship powered by steam turbines, it was the fastest in the world, capable of cruising at a maximum speed of 21 knots for 6,600 nautical miles. Its appearance triggered a renewed naval arms race on every ocean. Between 1908 and 1914, the navies of eight maritime powers launched more than sixty Dreadnought-equivalent battleships, including ten flying the American flag. The culmination came in 1908, when American shipbuilding experts held a series of planning conferences to design a battleship that would leapfrog ahead of the Dreadnought design.

The new battleship would have one major innovation: the ship’s boilers would be fired by oil instead of coal. Requiring less storage space on board, oil would also increase the ship’s operating range by as much as 40 percent, for a maximum of 10,000 miles at 10 knots. The new warship’s 30,500-ton displacement would also enable it to mount its ten 14”/45-cal. main guns in four turrets – a pair of triple-gun mounts and two twin turrets, creating a significant reduction in weight from the five twin turrets mounted on its immediate predecessors. Navy leaders opted to name this new “super-Dreadnought” after the thirty-sixth state to join the Union, and by coincidence, it would wear that same number on its hull: USS Nevada (BB-36).

As a crowd of several thousand shipyard workers, family members and dignitaries gathered for the ship’s launching on July 11, 1914. Shipyard tugs nudged the Nevada toward the pier where, over the next twenty months, she would take final form as the Navy’s first “super-Dreadnought.” One observer watching keenly as the ship slid down the ways into the Weymouth Fore River that day was the 32-year-old assistant secretary of the Navy. This would not be the only time that the Nevada would share a moment in history with Franklin D. Roosevelt.

During a two-year period spent in post-commissioning shakedown and routine training, America entered World War I on April 6, 1917. Nevada briefly deployed to the British Isles the following fall to join six other American battleships serving with the Royal Navy. The war ended without Nevada encountering the German High Seas Fleet, and she returned to the United States.

Over the next two-and-one-half decades, the battleship carried out a broad array of routine peacetime training missions with the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets. One of the ship’s career highlights came in 1925, when it joined an American naval armada on an extended five-month, 15,800-mile trans-Pacific cruise to Hawaii, Samoa, Australia and New Zealand. The cruise achieved the Navy’s twin goals of exchanging salutes and joint training with the allies “down under” while signaling to the Japanese Imperial Navy (from a distance) that American warships could operate in any part of the Pacific.

Another major milestone in Nevada’s career came in late 1927, when the ship entered Norfolk Naval Shipyard for a two-year modernization that dramatically altered her physical appearance. The two “cage” masts were replaced with soaring tripod masts, each topped off with a three-level observation and fire control station for guiding the main and secondary gun batteries. With spotter floatplanes now being used to guide the ship’s gunfire, shipwrights installed two 30-foot hydraulic catapults on her stern.

Other improvements were less visible but still significant: The hull was thickened with anti-torpedo blisters to minimize the threat of a warhead explosion. Six new and more efficient Bureau Express boilers rejuvenated her propulsion system. Her ten main guns were modified to increase barrel elevation from 15 to 30 degrees, boosting their effective firing range from 23,000 to 34,000 yards. And in recognition of the potential threat to the ship from enemy aircraft, shipwrights installed eight single-barrel 5”/25-cal. anti-aircraft guns. This was a step in the right direction, but far from sufficient, as the Navy would later learn to its regret.

For eleven years after leaving the Norfolk shipyard in 1930, Nevada operated as a unit of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Its routine training missions carried the ship from its home port in San Pedro, California to Panama, San Francisco, Puget Sound, Hawaii, Midway and other Pacific operating areas, with occasional forays into the Caribbean and Atlantic via the Panama Canal. And on December 5, 1941, the ship entered port for what its crew anticipated would be a quiet week of liberty ashore.

A CHANCE decision by a young naval officer in the pre-dawn quiet of December 7 made Nevada’s historic sortie during the Japanese attack possible. While standing the 0400-0800 watch as Officer of the Deck, Ensign Ernest H. Dunlap decided as a matter of routine to light off one of the ship’s six Bureau Express boilers. Under normal conditions, when Nevada tied up in port the engineers would shut down all but one of the ship’s boilers, using the one remaining online to provide power and electricity. Making his rounds on the sleeping ship that morning, Dunlap glanced at the ship’s engineering log and noticed that boiler No. 2 had been in use ever since the ship docked two days earlier. The 26-year-old Birmingham, Alabama native ordered fires lit under Boiler No. 6, and planned to switch the load once it reached full steam pressure.

Normally it would take the Nevada lighting off its five dormant boilers nearly three hours to raise enough steam to get underway. Fortunately for the battleship, Dunlap’s act ordering the second boiler online cut the time to just forty-five minutes after the Japanese attack began. But in that forty-five minutes, Pearl Harbor had already become an inferno.

Crossing a 4,000-mile swath of the North Pacific in twelve days under strict radio silence, the six aircraft carriers of the Kido Butai (carrier strike force) reached their launch point 230 miles north of Oahu at 6 a.m. on December 7. In quick, coordinated launches, the Japanese sent the first attack wave of 183 aircraft toward the ships at Pearl Harbor and six military airfields on the island. The first wave included fifty-one Aichi Val dive-bombers with a single 550-pound bomb that were targeted on three airfields and any warship targets of opportunity. A force of forty-five Mitsubishi Zero fighters would provide air cover. The main brunt of the attack force consisted of eighty-nine Nakajima Kate aircraft assigned to attack the American battleships: forty each carrying a single 1,750-pound aerial torpedo, and another forty-nine configured as high-altitude bombers with a solitary 1,750-pound armor-piercing bomb.

Lieutenant Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, a 39-year-old aviator with over 3,000 flight hours and an expert in high-level bombing, was overall commander of the aerial strike force. He personally led the first wave. Piloting one of the lead Kate bombers, Fuchida at 0753 gazed down at the crowded naval anchorage, and in the absence of any anti-aircraft gunfire or swarming American fighters, signaled First Air Fleet Commander-in-Chief Vice Admiral Chiuchi Nagumo on the carrier flagship Akagi the fateful dispatch signaling complete strategic surprise: “Tora, Tora, Tora.” Crewmen on the Nevada – like everyone else on Oahu – were just minutes away from the heart-stopping moment when peace exploded into war.

For Ensign Joseph K. Taussig Jr., the transition would be particularly brutal. Sound asleep in his stateroom that morning, he was awakened by a junior quartermaster of the watch, who whispered, “Mr. Taussig, it’s 0700. You have the forenoon watch, sir.” The 21-year-old Naval Academy graduate and son of a vice admiral hastily dressed and ate breakfast. It was going to be his first time ever standing watch as Nevada’s officer of the deck. It would also be his last.

Arriving on the quarterdeck at 0745, Taussig waited as Ensign Dunlap, the outgoing OOD, finished writing his entries in the ship’s log. He noticed a liberty party of a dozen sailors nearby, patiently waiting for a motor launch to pull up and take them ashore at 0800. He would later recall his biggest worry was “whether the correct-sized national ensign had been ordered for the raising of colors at 0800.”

Aft on the fantail, the Nevada’s band had already formed up to play the national anthem when at 0758, Bandmaster Oden McMillen glanced up and saw several aircraft approaching at low level from Southeast Loch directly to port. Just as McMillen raised his baton and the band launched into the national anthem, two Japanese Kate torpedo bombers flashed by. The gunner on the first plane opened fire with a rear-mounted machine gun, fortunately missing the musicians.

Taussig also saw the Kate torpedo bombers approaching. He watched as the first one dropped a torpedo into the harbor. “My reaction was merely to think of the welcome break in the Sunday morning tedium that we would have watching the salvage operation of digging the torpedo out of the mud,” Taussig recalled. Suddenly, multiple deafening explosions and soaring plumes of water erupted where the first of twelve aerial torpedoes slammed into the Oklahoma and West Virginia.

The Nevada was not on combat alert when the attack started, but neither was the ship or her crew completely asleep. The ship was equipped with eight .50-cal. machine guns mounted four each atop the two tripod masts in what sailors called the “bird baths.” Operated by the ship’s Marine detachment, the two positions were manned around the clock as a standard security precaution. Their gunners opened fire within a minute of the attack at 0802, shooting down one Kate that crashed within 100 yards of the ship.

As the battleship went to General Quarters, junior officers raced to assume duty stations normally manned by their superiors. In the absence of Captain F.W. Scanland, who was ashore along with most of Nevada’s senior officers, command of the ship fell to the senior officer aboard, Lieutenant Commander Francis J. Thomas. Another junior officer, Lieutenant Lawrence Ruff, was attending mass on board the hospital ship USS Solace anchored just 400 yards away off the north end of Ford Island when the first torpedo bombers came swooping in. At the sight of the first explosions, Ruff and others jumped into the Solace’s motor launch, which carried them back to the Nevada. Scrambling up to the bridge, he found Thomas and volunteered to supervise the bridge watch while Thomas commanded the ship from the Battle Two control station belowdecks.

Meanwhile, Taussig raced aft and climbed six levels to his combat station as air defense officer. His battle station was the ship’s starboard Mark 19 fire control director, an armored turret that controlled the fire of the 5”/25-cal. anti-aircraft guns on that side. Dunlap raced for the portside gun director.

When Taussig climbed into the director, he immediately saw that his guns were already firing under “local control,” aimed by each gun crew directly. “As I climbed through the door of the director, I was conscious that the cross hairs on my check sight were on an airplane, and I saw that it was hit almost immediately and went down trailing smoke,” he later recalled.

Now guided by Taussig, the five-inch guns began concentrated fire at the Japanese, adding to the ever-growing din of exploding bombs and torpedoes up and down Battleship Row. Taussig’s gunners later reported downing another Kate, which disintegrated when a shell set off its torpedo warhead.

Then the Japanese struck Nevada. Just as Thomas and Ruff began organizing an ad hoc maneuvering watch to get underway, the battleship shuddered from stem to stern. An aerial torpedo slammed into the port bow fifteen feet below the waterline between the two forward gun turrets. It blew a hole in the side 45 feet long and 30 feet high. When the ship quickly began listing to port, Thomas ordered counter-flooding of four void compartments on the starboard side. That stabilized the ship for the time being. They anxiously waited for the steam in Boiler No. 6 to reach full pressure, and for the duty engineering gang to get the other four boilers online. Since Nevada was not obstructed by another ship moored alongside, the acting CO was confident his team could get Nevada underway before the Japanese could strike a fatal blow.

All around Pearl Harbor, the attacking Japanese aircraft were wreaking havoc. Just four minutes after the first Kate roared overhead, Nevada’s sailors on deck watched in horror as two berths down channel, their sister ship, Oklahoma, slowly capsized after absorbing five torpedoes in her port side. Directly astern of the stricken battleship, West Virginia took seven torpedoes and also began rolling over, but quick counterflooding kept the ship erect. It slowly sank upright into the harbor mud.

At the same moment, a wave of horizontal bombers began dropping their ordnance on Battleship Row. Thomas noted in the ship’s deck log that several bombs fell close aboard the Nevada’s bow. Another three bombs struck Arizona in quick succession at its mooring just 100 feet away, and two more fell on Vestal tied alongside. The blasts started several fires, and a large plume of burning fuel oil began spreading toward Nevada. Before Thomas could even consider how to keep the flaming oil from threatening his ship, came the biggest wallop of all.

At 0805, the world seemed to vanish in an explosion and fire that both blinded and deafened Nevada watchstanders on deck: A Japanese bomb – actually a 1,760-pound armor-piercing artillery shell mounted with aerial fins – plummeted into Arizona’s forward hull, pierced through three decks, and exploded. It set off more than 100 tons of black powder, destroying the battleship and killing all but 335 of its 1,512-man crew. In seven seconds, the broken hull of Arizona lay on the harbor bed, its forward tripod mast leaning over as if bowing in defeat. A towering black cloud of smoke rose to the sky.

Joe Taussig would have no clear memory of the Arizona tragedy, or the simultaneous shock sailors everywhere felt as they watched Oklahoma slowly capsize. He was slewing the Mark 19 director around searching for a target when a Japanese fighter strafed Nevada. One of its 50-cal. bullets struck him in the left thigh, nearly severing his leg. “There was no pain, and because I was clutching the sides of the hatch as the director slewed around, I did not fall down,” Taussig recalled years later. “My left foot was grotesquely under my left armpit, but in the detachment of shock, I was not aware that this was particularly bad.”

Fellow crewmen lifted Taussig out of the director and placed him on a basket stretcher. Pharmacist’s Mate 2nd Class Ned B. Curtis, manning an aid station nearby, bandaged his wounded leg and doused him with morphine, later lowering Taussig to the main deck as Japanese warplanes strafed the ship. Joe Taussig’s war had lasted just ten minutes.

While Thomas monitored conditions from Battle Two, and Nevada’s bridge watch, including Lieutenant Ruff with Quartermaster Chief Robert Sedberry at the helm, waited for the engineering gang to get the steam boilers up to pressure, elsewhere in the ship other crewmen were desperately trying to keep their equipment functioning or carry out their specific tasks to help the ship get underway.

In the battleship’s forward dynamo room, Warrant Machinist Donald K. Ross and his small team were monitoring the electrical generator to ensure that it was correctly delivering power throughout the ship. When Thomas gave the order at 0820 to “single up” all mooring lines, one deck supervisor took matters into his own hands. Noticing that the sailors on Quay F-8 responsible for casting off the ship’s lines were taking shelter from a Japanese fighter strafing the berth, Boatswain Chief Edwin J. Hill jumped down from the ship, cast off the lines himself, then dove into the water and swam back to Nevada. The 5-inch gun crews and machine gunners high atop Nevada’s tripod masts continued to fire at the enemy aircraft overhead.

Thomas noted in the ship’s deck log that at 0820 hours the Japanese attack “slackened somewhat.” The acting Nevada CO could not have been more wrong. What he did not know was that the first attack wave had finished their passes along Battleship Row, but a second wave of 170 warplanes, including eighty Val dive bombers designated to attack any surviving ships, were closing in on Oahu.

Another blow then nearly halted Nevada in her tracks. A Japanese bomb from a Kate glanced off the bridge structure, penetrated the deck and exploded, killing or injuring a number of sailors and setting fires to the bridge and compartments beneath the forecastle. Far below, the engine room gang rushed to secure two boilers as water began flowing into the fire rooms. Several minutes later they were able to relight one of them, and by 0839, the ship had built up sufficient steam to get underway.

Nevada began slowly backing out from Berth F-8. Carefully edging around a nearby fuel pipeline, the battleship moved into the south channel and headed for the narrow Pearl Harbor entrance channel two miles away, and the open sea beyond. As the ship passed the smoking ruin of Arizona, deckhands saw three survivors swimming in the water and tossed them lines. Once aboard, they joined one of the starboard five-inch gun crews.

Aboard the battleship, crewmen struggled to keep her vital systems operating. Damaged by the first bomb hit, the forward dynamo room quickly filled with smoke and steam from a ruptured line. The temperature in the compartment soared to well over 120 degrees, and Ross ordered the rest of his crew to evacuate. He continued monitoring the dynamo as it churned electricity to the rest of the ship. At one point, blinded by the heat, steam and choking on smoke, the 30-year-old Kansas native fell unconscious. Crewmen rescued and revived the warrant officer, who rose to his feet, secured the forward dynamo room, and rushed aft to man the aft dynamo until he again lost consciousness from heat exhaustion.

Nevada passed slowly down Battleship Row, where sailors drenched in oil, grease and sweat frantically worked on the stricken behemoths to put out fires and rescue shipmates trapped by flooding and fire. As the ship passed capsized Oklahoma, several of her crew stood up and cheered loudly. Naval historian Gordon W. Prange would describe Nevada’s passage in elegiac terms:

By now Pearl Harbor was a hellpit of smoke – gray, brown, white, lemon yellow, black, and again black – acrid, foul, mushrooming billows erupting skyward, folding in and opening out like a mass of storm clouds. Out of this pall came a sight so incredible that its viewers could not have been more dumbfounded had it been the legendary Flying Dutchman – Nevada, heading into the channel, a hole the size of a house in her bow, her torn flag rippling defiance.

That scene lifted the hearts of countless American sailors as they struggled to respond to the devastating nightmare. Unfortunately, the spectacle of an American battleship underway at the height of the attack also pumped the adrenalin of scores of Japanese Val pilots overhead.

Circling high above the conflagration in his command aircraft, Fuchida saw the Nevada moving down the channel and instantly realized that if his second-wave dive bombers could sink her in the narrow channel to the sea, the rest of the Pacific Fleet would be hopelessly bottled up. “Ah, good!” he recalled thinking years later. “Now just sink that ship right there.”

At 0850, at least a half-dozen Val dive bombers swarmed the Nevada as it passed the sinking California at the lower end of Battleship Row. In the din of anti-aircraft fire and exploding bombs, several scored direct hits on the ship’s forecastle. The blast from one of them blew Boatswain Chief Hill and his group of deckhands over the side, killing them instantly.

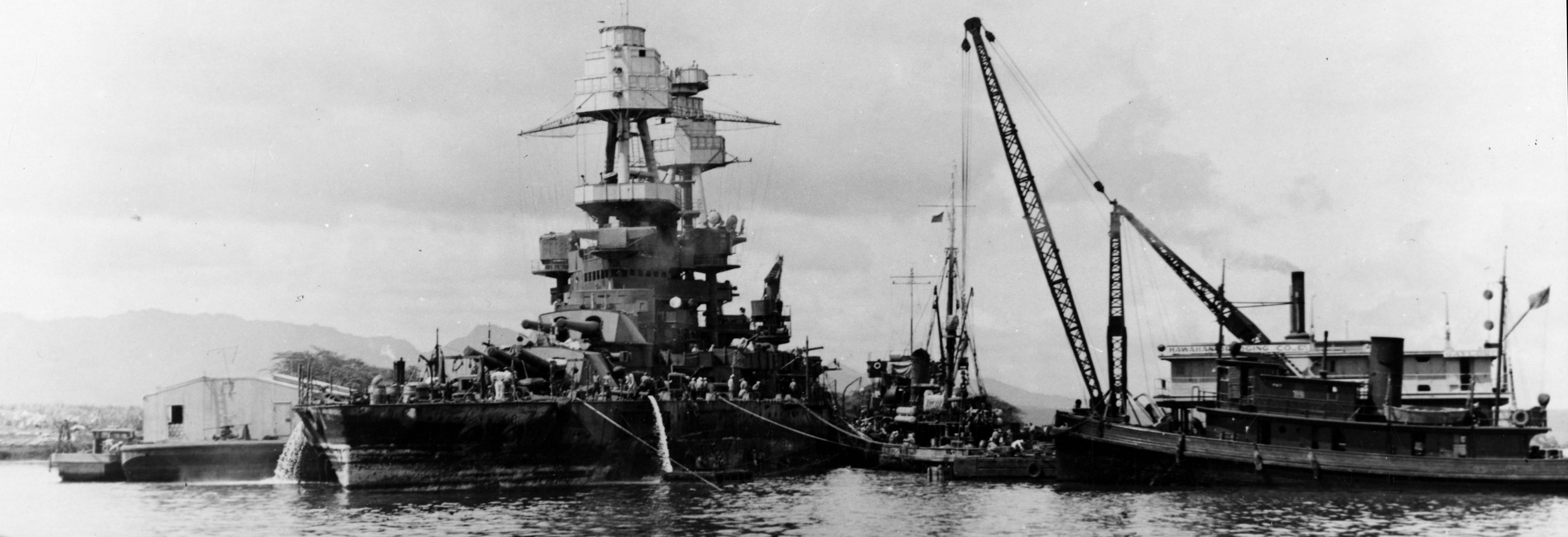

There were at least a dozen near-misses that sprayed shrapnel and water across the ship’s decks, but five scored hits. Salvage crews later determined that three bombs struck and penetrated the ship forward of main Turret No. 1, while another pair fell between the ship’s massive exhaust stack and the boat deck immediately aft. With fires spreading uncontrollably and flooding accelerating, the senior port admiral flashed Nevada a message ordering it not to attempt passage through the narrow entrance channel. At 0910 Thomas decided to beach the battleship bow first on the east side of the channel entrance between the shipyard’s Floating Drydock No. 2 and Hospital Point.

But before Nevada’s crew could take any more steps to secure their severely damaged ship at this temporary spot, a spectacular explosion erupted just several hundred yards away. A bomb from a Japanese Val struck the destroyer Shaw (DD-373) in Drydock 2. The impact set off the destroyer’s forward ammunition magazines in a massive fireball, demolishing the front half of the ship and sinking the floating drydock. Flaming debris flew as far as a half-mile away, much of it raining down on Nevada.

Unable to anchor because a bomb had destroyed the windlass and other equipment, Thomas decided to move the ship to Wapio Point on the western side of the entrance channel. Five minutes after Captain Scanland managed to return aboard his ship at 0915, two harbor tugs nudged the Nevada free from Hospital Point and it backed at two-thirds speed across the waterway, intentionally grounding itself stern first. The ship continued to settle into the mud, its flooding and fires still out of control.

Two hours after the Japanese first struck at 0755, the last of the second wave aircraft flew off to rejoin the Kido Butai north of Oahu. Still on fire and gradually sinking as the seawater infiltrated her hull, the ship had sustained 50 fatalities and 109 crewmen wounded. For the Nevada, it was the end of the Japanese raid. But it was also, for the battleship, the beginning of a very long war. She was repaired and upgraded, and went on to serve in the Aleutians, Atlantic convoy escort duty, the Allied liberation of southern France and Normandy, where she served as a flagship, and in the climactic battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Epilogue: In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Lieutenant Commander Thomas and Ensigns Taussig and Dunlap were among fifteen members of Nevada’s crew awarded the Navy Cross, the service’s second-highest decoration for valor. So too was Pharmacist’s Mate Curtis. Boatswain Chief Hill was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. And Warrant Machinist Ross was one of only five living recipients of the Medal of Honor for his heroic service on December 7, 1941.

The second part of this essay is "Revenge of the Nevada" in the June 2021 American Heritage.