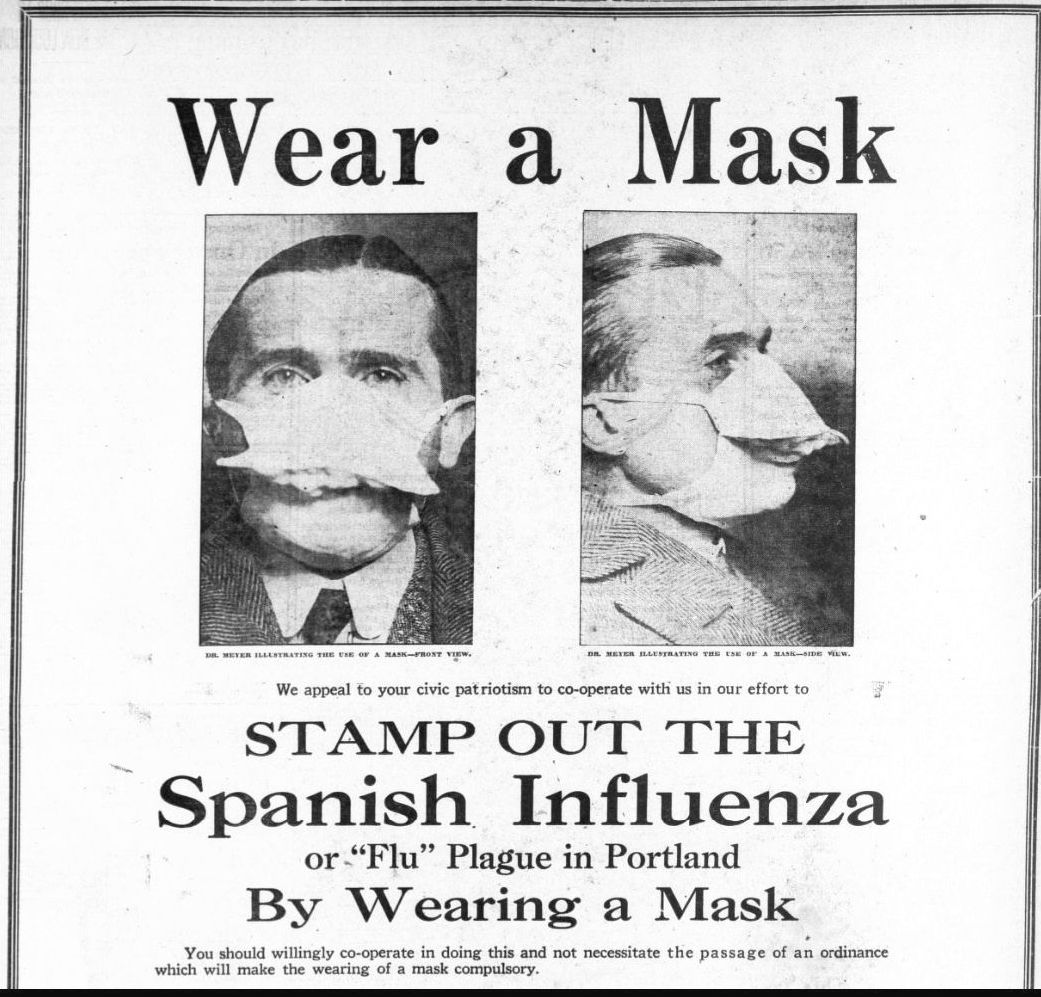

Masks and "social distancing" are nothing new. Over the centuries, Americans have suffered terribly from smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, pellagra, influenza, polio, and other pandemics.

-

Winter 2021

Volume66Issue1

We have become all too familiar in the last year with face masks, social distancing, lost income, empty streets, and the gnawing fear of being the next to be stricken. Recently, our downtown cities resembled London during the Great Plague — “the streete thin of people, the shops shut up, and all in mournful silence, as not knowing whose turne might be next,” as John Evelyn penned in his diary in 1665.

The reality in 2020 may have shocked our fellow citizens, but it's not a new phenomenon in America. In fact, a pandemic has appeared in almost every generation since the earliest settlements on the continent.

Many of these pandemics profoundly changed society. Smallpox enabled Cortés to conquer Mexico and its vastly larger Aztec army. A few years later it arrived in New England, carried by a European sailor shipwrecked on Cape Cod, as Charles Mann wrote in "A Pox on the New World" in American Heritage. The terrible disease quickly spread among Native American tribes, causing high fever, chills, and scarring of the skin in those who survived. Indians “died in heapes, as they lay in their houses,” the merchant Thomas Morton recalled.

In evolutionary history, the native populations on the American continents had few pandemic diseases before Europeans arrived— no smallpox, influenza, measles, or malaria. So there was little inherent immunity from these new diseases, or understanding about how they spread. Sometimes individuals who seemed healthy but were infected would flee to neighboring villages, carrying the disease with them.

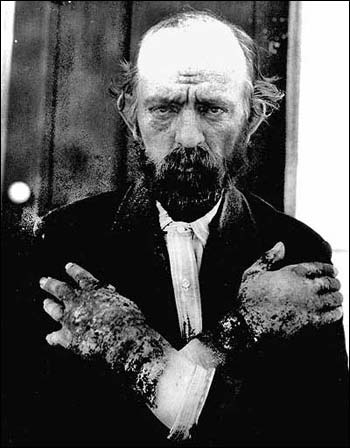

As smallpox crossed the continent, it wiped out entire Indian tribes, an estimated 70 percent of the total population of North America. Anger over the introduction of disease fueled Indian animosity against white settlers. But the reduction of native populations in New England enabled European settlements to survive in the decades that followed these pandemics.

Prof. Alfred W. Crosby of the University of Texas also wrote about the sad history of smallpox and Native Americans in American Heritage. The epidemic “struck the coast of New England, devastating the tribes like an autumnal nor’easter raking leaves from the trees.” One colonist informed the Wampanoag tribe that Europeans had the plague as their ally, in addition to gunpowder. “The God of the English has it in store, and could send it at his pleasure, to the destruction of his or our enemies.”

The Great Plague in England killed an estimated 100,000 people in 1665 and 1666, including a quarter of the population of London, and caused many immigrants to flee to the New World. But the plague bacterium went with them, carried by fleas on rats which swarmed in the holds of ships.

In 1721 a smallpox epidemic infected half the inhabitants of Boston and killed 844. Dr. Laurence Farmer wrote in American Heritage that the famed preacher Cotton Mather tried to convince the town’s physicians to experiment with a new method called “Inoculation,” which he had learned about from African slaves. But the experts were incensed and none would countenance it. The idea of puncturing the skin of a healthy person and inserting pus from the blisters of a smallpox sufferer appalled the doctors and most of Boston were roused against Mather. The debate raged for weeks and reached a crescendo after Mather convinced one doctor, Zabdiel Boylston, to inoculate his young son and two of his slaves. A bomb was thrown into Mather’s home, but the fuse failed to ignite it.

Eventually, 240 persons in Boston underwent inoculation and only six died, or one-seventh the mortality of others who contracted the disease. Eventually, Boylston traveled to London and published the results of his efforts as Historical Account of the Small-Pox Inoculated in New England. He became a fellow of the Royal Society two years later and was much honored when he returned to Boston including by his great-nephew, John Adams, who later insisted on being inoculated himself with his family.

Malaria was another scourge that would have a profound impact in the Americas. Endemic in Europe for thousands of years, it was responsible for the shifting fortunes of city states in ancient Greece. Malaria became known as the “Roman fever” because it was so common in the Italian peninsula and may have led to the fall of the Roman empire in the fifth century. During the Renaissance the disease got its new name from mal aria ('bad air' in Medieval Italian), as it was thought to be spread in miasmas or fumes, especially in swampy areas. In England, this “marsh fever” decimated populations in low-lying coasts.

When the malaria parasite showed up in the American colonies, it had a profound effect here as well. The Anglo population was so decimated in the southern colonies in following years that demand increased for slaves from Africa, who were believed to be immune from the disease.

In 1779 during the American Revolution, Lord Cornwallis moved much of the British army to the southern Colonies and the following spring captured Charleston. Patriots won some important battles at Kings Mountain and Cowpens, but the real counterattack was led by the malaria parasite, which sickened half of the British army. Cornwallis retreated to Yorktown, where most of the other half of his army fell sick. The British surrendered and retreated home, defeated as much by an invisible foe as by the rebels.

Dr. Farmer also wrote for American Heritage about the yellow fever epidemic in 1793 that drove George Washington and members of the Cabinet and Congress out of Philadelphia. The capital of the young American republic was the most populous and prosperous metropolis in the United States at the time, but it soon looked like a ghost town with houses and shops deserted and boarded up, but even with “social distancing” one in ten residents died of the cruel disease. Its symptoms started suddenly, with shaking and a high fever, then headaches, vomiting, and delirium. By the third or fourth day the victim’s entire skin was yellow. Doctors treated their patients with bleeding and other ineffectual remedies. Not until October did the rate of dying abate.

During the Spanish-American War, fourteen times as many men died of tropical diseases as from enemy action. The losses were so severe that President McKinley was weighing the humiliation of withdrawing from Cuba when word came of Spain's surrender, wrote wrote Jane Colihan in “The Spanish-American War: Conquering Yellow Fever." After Maj. Walter Reed proved that certain mosquitoes caused yellow fever, Maj. William Gorgas began a campaign to eradicate them and within a year there were no cases in Havana for the first time in over a century. The medical breakthrough enabled the U.S. to then build the Panama Canal, although vaccines would not be developed for yellow fever until the 1930s.

The first epidemic of Asiatic cholera struck the United States in 1832. American Heritage’s founding editor, Bruce Catton, wrote how the disease struck mostly in the poorer sections of cities. Many wealthier people thought this was God’s doing, since people in the slums lived in unsanitary conditions. “It was impossible to do anything about it, because even the wisest men did not know what to do and partly because of the old belief that cholera came from vice and vice came from poverty and poverty was pretty largely self-inflicted,” Catton says many people thought.

But then the disease spread even to quintessential American towns such as Kenosha and Sandusky before eventually playing out. One positive development from the cholera epidemic was that many municipal authorities realized they ”ought to do something about slums, filthy streets, contaminated water systems, and overcrowded housing” in the poorer parts of cities, says Catton.

There were continued outbreaks of yellow fever after it had devastated Philadelphia in 1793. Norfolk, Charleston, Mobile, and Galveston all suffered from epidemics and New Orleans was visited with four outbreaks in the 1850s that left a total of 20,000 dead.

Bernie Weisberger recalls how yellow fever came north up the Mississippi from New Orleans and attacked Memphis in 1878, changing the city forever. Before it had run its course, the epidemic that year ravaged other cities, big and small, in the Mississippi, Ohio, and Tennessee river valleys – two hundred places in all, and 20,000 dead. But Memphis was hit most savagely. Many people moved away and ever returned and some observers believe the city never really recovered. Memphis emerged as a sanitary, modern city, but a measure of sophistication and cosmopolitanism it enjoyed before the devastation had disappeared.

Stories of the efforts of doctors and researchers to find causes for the various epidemics – and treatments – can read like a “who-done-it.” But the sad tale of Typhoid Mary, told by Mark Sufrin in American Heritage, really is a murder mystery. In August 1906 the daughter of a New York banker developed symptoms of typhoid fever – a high fever and low pulse rate, nosebleeds, nausea, and diarrhea. Then her mother and other members of the household fell ill. An inspector was brought in to try to find out a cause, and he checked out all the usual sources of infection such as sanitation and water supply. But the cook who the mother had hired from a New York employment agency had disappeared and couldn’t be found for an interview.

The inspector dug into Mary Mallon’s history of employment and found dozens cases of typhoid fever in her past from Manhattan to Maine. When he finally located and confronted Mary, but she attacked him with a large fork. Eventually, policemen were brought in and she was detained. But the contagion spread until nearly twenty-three thousand died in the United States in the year alone that year.

An epidemic largely forgotten today that killed thousands in the U.S. was the scourge of pellagra, which became a national scandal in 1914. No experts could determine why this disease spread across the country, especially in the south. Patent medicines to combat the disease flourished as doctors tried more than 200 remedies, from arsenic to electroshock. Experts did discover that the disease had been around longer than thought. In fact, pellagra rather than typhoid may have killed hundreds of Union prisoners in Andersonville prison in 1864.

The mystery was finally solved by “a medical Sherlock Holmes who fought ignorance, politics, and injustice as well as the disease,” says Daniel Akst in "The Forgotten Plague." The story of how Dr. Joseph Goldberger, an epidemiologist with the U.S. Surgeon General’s office, solved this medical mystery reads like a detective novel.

Sadly, Goldberger also had to fight the scourge of anti-Semitism as he worked. Despite clear results from his research, “his findings weren’t accepted,” writes Akst. “He was attacked at medical conferences, in the press, and even from the pulpit.” Doctors were convinced pellagra was caused by an infection or something people ate. Goldberger, on the other hand, believed it was caused by something they didn’t eat.

The medical establishment continued to assail Goldberger, believing that pellagra resulted from such sources as “corn bread, Italians, amoebae, cane sugar, and infection.” An official commission set up to investigate the epidemic announced in 1916 after four years of work that it was caused by infection, not diet – directly contradicting Goldberger’s conclusions. “NOT DEPENDENT UPON DIET, Best Way to Combat the Disease Is with Efficient Sewerage Systems,” read the headline in The New York Times.

It would take several decades for the medical community to come around to the realization that Goldberger was right and that a deficient diet caused pellagra. But sadly he died of cancer in 1929 before that came to pass. In a further disappointment, Goldberger was nominated for the Nobel Prize five times, but never won. At least at his death newspapers generally lauded him, although they often printed condescending headlines such as “Jew Discovered Cause of Pellagra” and “The Wandering Jew who Whipped Pellagra.”

The worst epidemic ever to hit the United States is still, of course, the so-called “Spanish flu.” The tragic story of this medical forest fire was told in American Heritage by the famed historian Joseph Persico in "The Great Flu Epidemic of 1918." Influenza had been around for a long time, even wiping out an Athenian army in 412 B.C. according to none other than Hippocrates himself. It afflicted soldiers during the Revolution and again in the Civil War, but by 1918 it ranked about tenth as a cause of death influenza in the U.S., well behind heart disease, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and cancer.

At the onset of the flu pandemic, efforts of epidemiologists to shut down large gatherings were thwarted. In Kansas City, Missouri, were “Boss” Tom Pendergast refused to close saloons and other the places of amusement, some 1,800 persons would eventually die of influenza. Ultimately, the final reckoning was 548,452 lives lost in the United States, nearly ten times as many Americans from the disease as had been killed in eighteen months of World War I.

Another terrible scourge of the time was polio, which first hit the United States with full force in the summer of 1916. As the former Editor of American Heritage, Geoffrey Ward reports, six thousand Americans died of polio that year, most of them children, and at least twenty-seven thousand more were permanently affected. “Italian immigrants were blamed early on,” says Ward. “So were cats, ice cream, automobile exhaust; one theory held that sharks had inhaled poison gas drifting seaward from the Western Front, then somehow brought it with them all the way across the Atlantic.”

Ward, who is himself a survivor of polio, credits Franklin Roosevelt and his well-publicized struggle against paralysis for helping to remove its stigma. And FDR invested most of his personal fortune in a treatment center at Warm Springs, Georgia, which led to the establishment of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in 1937. While there were setbacks and embarrassments in the war on polio, he believes it was “one of the great American success stories” of the century.

Other essays in American Heritage deal with pandemics of a different kind. In “The Persistence of the Serpent,” long-time contributor Bernie Weisberger looks at the century-long efforts of the American Sexual Health Association to fight sexually transmitted diseases. It has been a long battle against entrenched attitudes. One doctor feared that eradicating venereal disease would put mankind “wholly under the domination of the animal passions.”

Dr. John Meyer looks at how lung cancer rose from obscurity to take its place among the nation’s leading killers. He points out that in 1919, a doctor called in medical students to look at a case of lung cancer, a disease so rare that most of them would supposedly never see it again. In the early years of the 20th Century, most smokers chose cigars. “The cigarette was seen as somewhat effete and faintly subversive,” points out Dr. Meyer. “Smoking was an almost wholly male custom.”

The increasingly widespread use of cigarettes over the next decades would have profound effect on the nation’s health. Although a 1932 paper in the American Journal of Cancer accurately blamed the tars in cigarettes for the formation of the disease, it was not until the Sloan-Kettering Report in 1953 announced that researchers had produced skin cancers in mice by painting the tars from tobacco smoke on their backs.

Tobacco companies fought back, of course. The R. J. Reynolds launched a campaign claiming that “more doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette!” The number of deaths from lung cancer per thousand Americans rose ten-fold. In 2020, an estimated 228,820 Americans will be diagnosed with lung cancer, and 135,720 deaths will be attributed to the disease according to the American Cancer Society. It is far and away the leading cause of cancer deaths in our society, more than colorectal, breast and prostate cancers combined, and cigarette smoking is responsible for an estimated 85 percent of the cases.

Today, we honor the health care workers who risk their lives – and even the health of their families – to fight a terrible pandemic. And it reminds us of Dr. Benjamin Rush, selflessly trying to save Philadelphians from yellow fever in 1793. Or epidemiologist George Soper working tirelessly to track down Typhoid Mary. Or Dr. Joseph Goldberger fighting ignorance, anti-Semitism, and the medical establishment to bring an end to pellagra, a scourge mysteriously killing thousands and afflicting hundreds of thousands more across the U.S.

These are true American heroes. As the great Roman statesman Cicero said, “Nothing brings men nearer to the gods than giving health to their fellow creatures.”