There was widespread fraud, especially in the swing state of Florida. We are talking, of course, about 1876.

-

Winter 2021

Volume66Issue1

Editor’s Note: Roy Morris Jr. is a contributing editor for MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History and the author of nine books, including a definitive history of the 1876 Presidential election, Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876, in which portions of this essay first appeared.

Incumbent President Donald Trump, seeking to explain his reelection loss to Democratic candidate Joe Biden, tweeted three weeks after the 2020 election that it had been “the most corrupt election in American history.” There was no concrete proof of that charge, according to various state and federal courts, campaign officials and election certification boards.

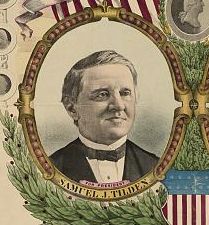

But even if Trump’s accusations had proven true, the 2020 election still could not have laid claim to being the nation’s most corrupt presidential election. That dubious distinction long since had gone to the 1876 presidential contest between Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio and Democratic nominee Samuel J. Tilden of New York. No other presidential election even comes close.

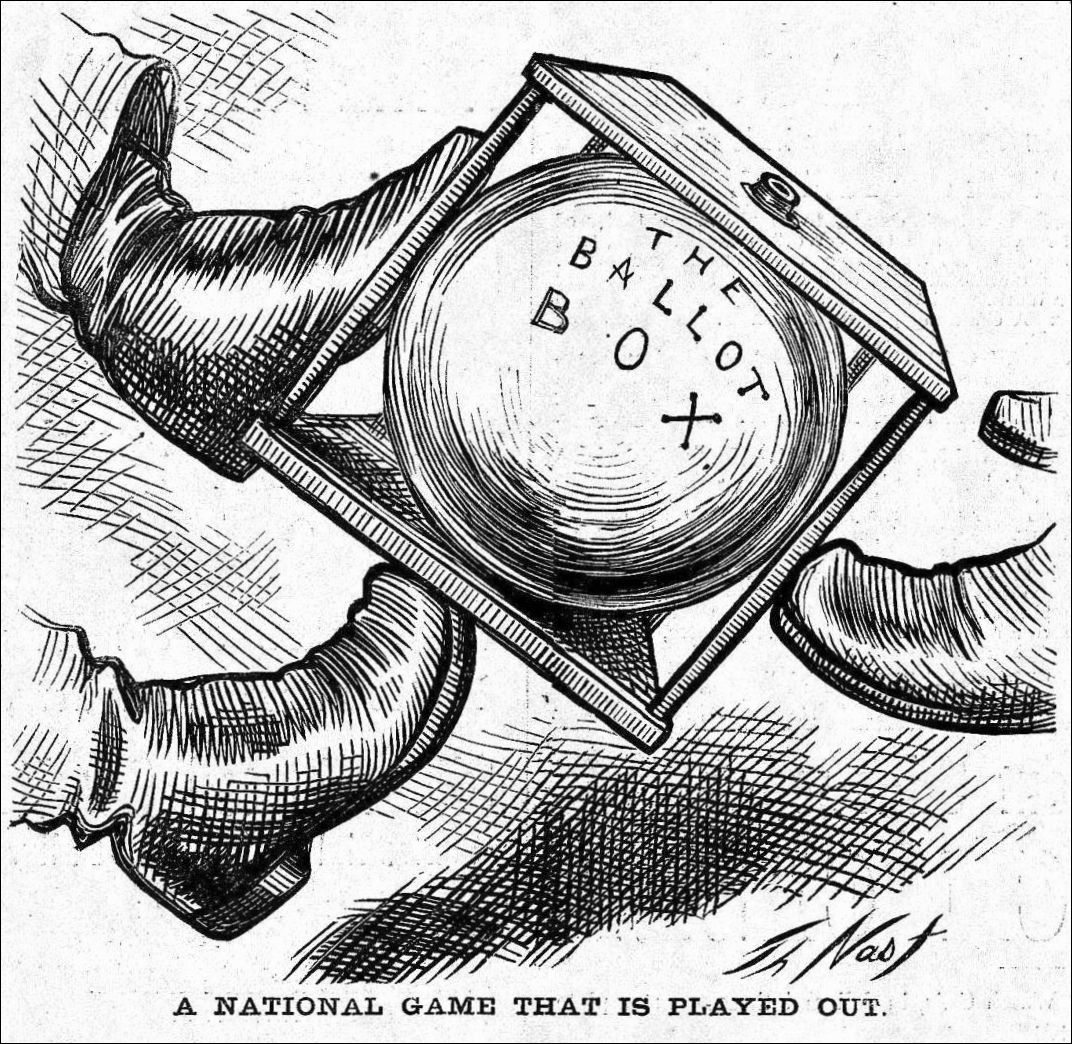

Like the razor-thin election of 2000 between George W. Bush and Al Gore, the 1876 race also involved a few hundred votes in the state of Florida and was ultimately decided by the vote of a single Republican member of the U.S. Supreme Court. In both those elections there were charges of fraud, intimidation, lost ballots, and racism. Hordes of political operatives descended hungrily on the state, while the nation waited, anxiously if not breathlessly, for the winning candidate to be determined. When it was over, four months after election day, the candidate who probably had lost the election in Florida and definitely had lost the popular vote nationwide nevertheless was declared the winner, not just of Florida’s electoral votes but of the presidency itself.

The result was a singularly sordid presidential election, perhaps the most bitterly contested in the nation’s history, and one whose eventual winner was decided not in the nation’s multitudinous polling booths but in a single meeting room inside the Capitol, not by the American people en masse but by a fifteen-man Electoral Commission that was every bit as partisan and petty as the shadiest ward heeler in New York City or the most unreconstructed Rebel in South Carolina. It was an election that did little credit to anyone, except perhaps its ultimate loser.

As Karl Marx famously observed, history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. But if some presidential elections—including the aftermath of this year’s race—have sometimes resembled a farce, the 1876 election was nothing less than a tragedy. Ironically, in a year that saw the United States celebrating the centennial of its birth, the American political system nearly broke apart under the powerful oppositional pull of party politics, personal ambitions, and lingering sectional animosities.

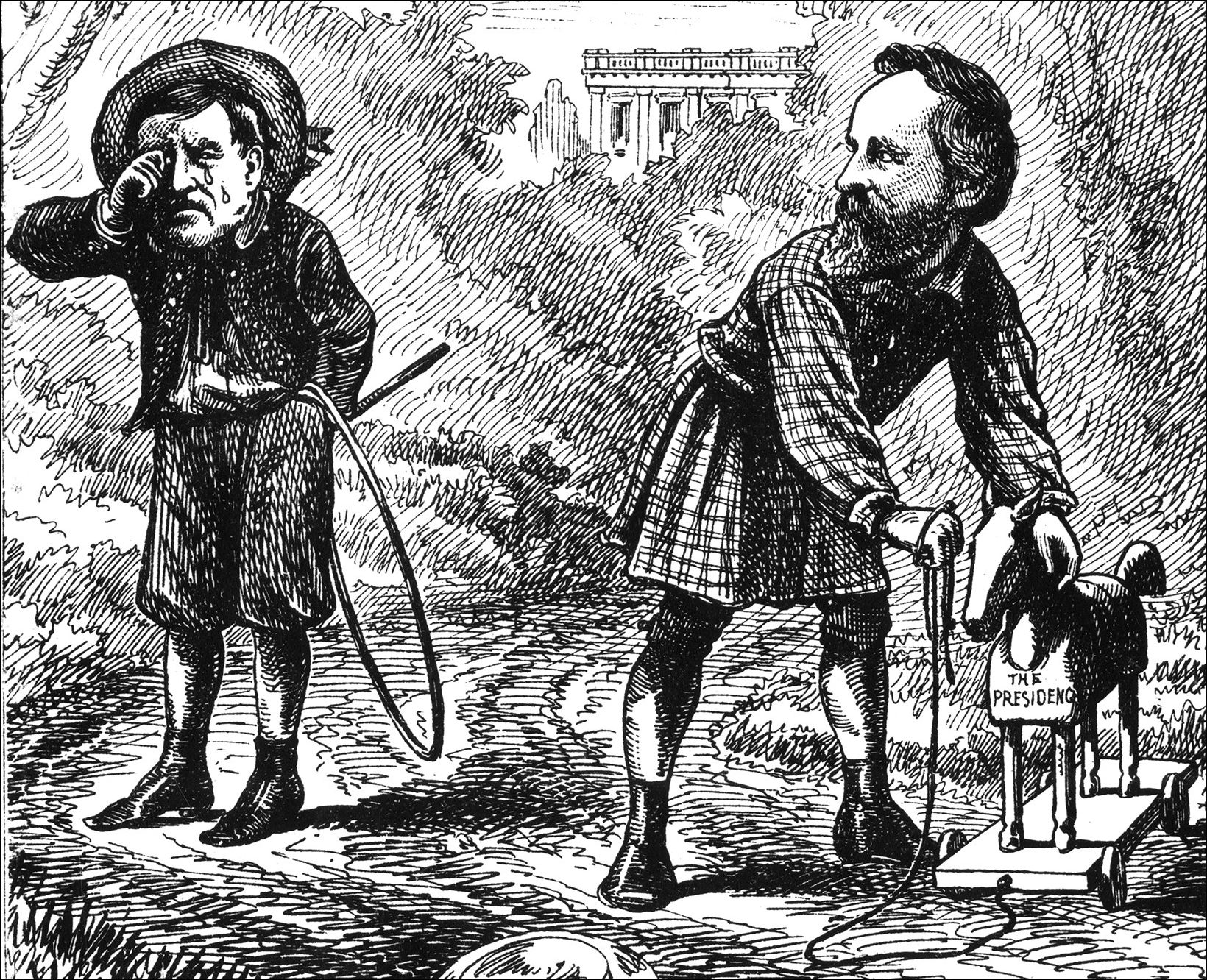

In a larger sense, there were no real winners in 1876. Rutherford B. Hayes did eventually take the presidential oath of office — not once but twice, in the space of three days, as events transpired — but in both personal and political terms he was as much a loser as the man he defeated.

The shameless ways in which Samuel Tilden’s electoral triumph eventually was overturned so compromised Hayes that, had he not already declared that he would serve only one term as president, he still would have been virtually a lame duck from the day he took office. As it was, his legal and moral title to the presidency was never accepted as legitimate by at least half the country, and he has been tarred ever since with such unflattering nicknames as “His Fraudulency,” “the Great Usurper,” and “Rutherfraud B. Hayes.”

As for Tilden, no one, not even fellow Democrat Al Gore in 2000, came so close to becoming president without actually being declared the winner. Gore received 540,000 more popular votes than George W. Bush, while Tilden got, proportionally, the modem equivalent of 1.3 million more popular votes than Hayes. Some of those votes, however, came from three southern states — Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina — where Tilden’s apparent victory margins were immediately contested by the Republicans, who still controlled the statehouses there and, more importantly, the returning boards that would formally certify the election results in each state.

Although Tilden, like Gore, officially lost the state of Florida, he almost certainly won the state of Louisiana, only to have it stripped from his electoral column in one of the most brazen political thefts in American history. If Gore was stopped figuratively at the gates of the White House, then Tilden, needing only one more electoral vote to win the election, was stopped at the very door to the Executive Mansion. Each man had a plausible claim to victory, but Tilden’s was much more plausible. Indeed, both he and Hayes went to bed on election night believing that Tilden had won.

The chairman of the Republican National Committee believed it, too; he went to bed with a bottle of whiskey. Had it not been for the dramatic, late-night intervention of two canny Republican politicos and a bitterly partisan newspaper editor, the election would never have been contested in the first place, and the nation would not have been subjected to four long months of bold-faced political chicanery masquerading as statesmanship.

Tilden and Hayes were not the only losers in 1876. By formally acquiescing to what historian Paul Johnson has aptly termed “a legalized fraud,” leaders of both parties in Congress heedlessly fostered an atmosphere of mutual suspicion, antagonism, and hatred that lingered over the political landscape for the better part of a century. The election and its aftermath gave rise in the South to the infamous Jim Crow laws that officially sanctioned the social and political disenfranchisement of millions of southern blacks.

The Republican party in the South was overthrown, and the unprecedented experiment in social engineering known as Reconstruction came to an abrupt, if largely predetermined, end. It would be another ninety years before southern blacks stepped free from the shackles of legalized segregation and a radically different Republican party reemerged as a viable political force in the South. At the same time, more than four million Democratic voters, in the North as well as the South, saw their ballots effectively rendered meaningless; and the shining cause of political reform, which Tilden long had championed and for which the American people openly hungered, guttered out in the shadows of a cynical political compromise that few people wanted and fewer still respected.

The election itself, in many ways, was the last battle of the Civil War. When Judson Kilpatrick, Hayes’s old Union army comrade, advised him to wage “a bloody shirt campaign, with money,” in Kilpatrick’s home state of Indiana, he might just as well have been speaking of the country as a whole. The Republican party, embattled and embarrassed by the myriad scandals of President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration, fell back on the tried-and-true method of sectional division known evocatively as “waving the bloody shirt.” With the Civil War less than a dozen years in the past, and a resurgent Democratic party in the South threatening to retake control of the region, the Republicans insistently urged their supporters to “vote as you shot.”

Behind this nakedly emotional appeal lay the pervasive worry on the part of northern veterans that the benefits they had won on the battlefield — not least of which was the right of 700,000 former slaves to vote freely and openly in political elections — were about to be lost at the polling booth.

On the other side of the coin was the palpable desire of Democrats everywhere to “throw the rascals out,” as New York Sun editor Charles A. Dana memorably demanded, to exact some revenge, however belated, for the numerous indignities inflicted on them by Republicans. Such indignities ranged from unsubstantiated charges of disloyalty in the North to military defeat and occupation in the South. Both northern and southern Democrats were united in their hatred of the corrupt Grant administration and in their belief that Tilden would usher in a new era of honest government and personal accountability.

The battle lines were dearly drawn and intensely defended. If it is true, as Karl von Clausewitz said, that war is merely politics by other means, then the reverse is also true. More than any other election in American history, the election of 1876 was war by other means.

Like many close and bitterly fought presidential elections, the Hayes-Tilden contest of 1876 was a riveting personal struggle between two unique, humanly flawed individuals with very different strengths and weaknesses. Tilden, nine years older and a good deal more experienced in national politics than Hayes, was a highly organized if somewhat cerebral politician with longstanding credentials as a proven reformer. His appeal was intellectual, not personal, and his tendency to aloof self-containment would cause him to be strangely passive at the most inopportune time — when the presidency itself was hanging in the balance.

Hayes, conversely, was a placid, outgoing individual with an unshakable belief in his own essential rectitude. This characteristic would serve him well when he confronted — and carefully overlooked — evidence of electoral misbehavior by some of his closest friends and supporters. Unhindered by doubt and buoyed by an inner strength he had discovered as a volunteer soldier in the Civil War, Hayes ironically proved to be a better practical politician than Tilden, who had spent virtually his entire life preparing for the presidency. It would prove to be a crucial difference.

In the century and a quarter since the election of 1876 took place, the Hayes-Tilden contest has receded in the national memory. Partly this is due to the peculiarly American habit of historical indifference, of always looking ahead rather than looking back, where, as Satchel Paige once warned, “something might be gaining on you.”

Partly, too, it is due to the equivocal way in which modem historians have generally treated the election. Recognizing that partisans on both sides were guilty of engaging in ethically questionable and sometimes illegal activities to suppress or reduce the votes of their opponents, historians have carefully straddled the line between corrupt Republican election practices and violent Democratic campaign abuses.

The tendency of historians in recent years, influenced to a degree by heightened sensitivity to the racial implications of the election, has been to excuse Republican fraud as a necessary antidote to Democratic intimidation. Even if Hayes (so the thinking goes) stole the election from Tilden, he was only stealing back what the Democrats already had stolen from him. We do not subscribe to such moral relativism: many wrongs do not make one right.

Primarily, however, the relative obscurity of the 1876 election is due to its peaceful resolution, an outcome which at the time seemed far from inevitable. Indeed, one ill-chosen word from Tilden might well have ignited another Civil War, this time between rival political parties rather than discrete geographical regions.

Both Hayes and Grant made it clear that they were prepared to go to any lengths to prevent the Democrats from returning to power. Tilden was not. “We have just emerged from one Civil War,” he said. “It will never do to engage in another; it would end in the destruction of free government.”

That Tilden had the good grace and inherent patriotism to avert such a social catastrophe was the one inspiring element in a distinctly uninspiring election.

How Hayes and Tilden, two essentially decent men, came to play reluctant leading roles in the most corrupt presidential election in American history is a story that still deserves to be remembered today, both for its inherent dramatic interest and for its cautionary relevance to recent events.

History, after all, is memory, whether its lineaments be tragedy or farce.