Eighty minutes before Pearl Harbor, Japanese troops stormed ashore at Kota Bharu in Malaysia and fired the first shots of World War II in Asia.

-

Winter 2023

Volume68Issue1

Editor's Note: Photographs are by the author, unless otherwise credited.

Zafrani brings bullets.

His cousin, sitting at the desk of the Tourist Information Center, had called him up, told him to hurry over. There’s an American guy here who wants to see where World War II in Asia really began.

I wait for Zafrani in this cheery red-and-yellow building with the typical bumbung pajang roof across from a small circular park that welcomes one and all to Kota Bharu, “The Islamic City,” from the bleak Thai border city of Sungai Kolok.

Before I crossed over, I spent an hour in that town waiting for a bus or tuk-tuk to take me to Harmony Bridge, which spans the river running between Thailand and Malaysia. Walked around in the neighborhood near the station, killing time, half anticipating a shattering blast, shrapnel, blood, and pieces of people strewn on the street. But the Muslim separatists are quiet today.

In this part of Thailand — the three southernmost provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala — more than 7,000 people have been murdered since 2004. The killers want a separate state. Sometimes, they shoot or slice up Buddhist schoolteachers because they're Buddhist.

I’m headed to see British pillboxes and the beach where the Japanese landed, the place where the march through Malaya and into Singapore started.

Zafrani Araffin arrives in about 30 minutes. He’s a short, chunky fellow in his 40s with deep tan skin and a bearing as sweet as I've ever encountered. I ask him what he does for work. “My job is at a bank.” I can tell he doesn't want to talk about it. His passion is the history that almost no one else in Kota Bharu or Kelantan state or Malaysia or anywhere else on the globe knows or cares about.

“The Second World War in Asia started here,” Zafrani explains. “The Japanese attacked British forces at Kuala Pak Amat beach about 80 minutes before they bombed Pearl Harbor. Look at these bullets! I found them on the beach.” Zafrani glows with pride.

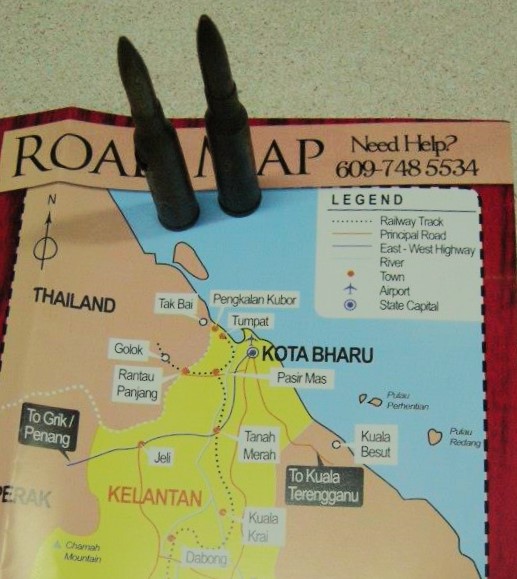

He has come with his older brother, Amran. They're Muslim. They could not be friendlier. I could not be luckier. Zafrani promises to take me on a tour tomorrow. I have my Kota Bharu road map on the desk. He hands me two 6.5 x 50-millimeter bottle-necked, semi-rimmed cartridges from a Type 30 Arisaka infantry rifle. I don't know what to do with them.

Is he giving me some of the first shots fired in a war that left almost 30,000,000 people dead?

On December 3, 1941, Major General Takumi Hiroshi led his 23rd Infantry Brigade down from Hainan island in China, through the Gulf of Tonkin. When the Japanese attacked Thailand, Thai forces in Nakhon Si Thammarat, Songkhla, and Pattani put up a good fight for a day. Then the fascist Thai Field Marshal Phibun in Bangkok made a deal with the devil, allowing Hirohito's troops to use Thailand as a corridor to Burma, Malaya, and Singapore, in exchange for which Thailand would not be taken over, and it got to annex part of northern Burma and reacquire sultanates in the north of Malaya that it had earlier signed over to the British.

One day of resistance by a few score brave soldiers. And then the collaboration. The Death Railway. The Asian reign of misery ended by two atomic bombs.

The next morning, my guide is brimming over with enthusiasm, like a kid going to his first pro baseball game. A few minutes into the ride, he tells me: “I’ll take you to a pillbox.”

In about 10 minutes, we slow down near a drab two-story shopping center. Zafrani pulls up to a curb facing a park across the street and points to a white stone tower. “Veterans of the Takumi Detachment had that put up several years ago. You can go look at it while I do some shopping.” He has seen this thing enough, probably driven past it thousands of times. I check it out. The clock at the top of the 20-foot-high structure is long gone. In 1988, Japanese vets consecrated it in memory of their comrades who died in the sand as they crawled on Kuala Pak Amat beach under fire from the mainly colonial Indian forces blasting away through slits in the pillboxes.

There are two small, black, polished-marble plaques at eye level –- one in Japanese, the other in English.

MAY THE CLOCK

STRIKE THE TIME

FOR

EVERLASTING

PEACE AND LIBERTY

Some local folks weren’t going for that post-war peace mantra of Japan. They put up a ladder, climbed to the top, and tore off the clock. Now, no one comes here. No one sits on the benches. There is no bell to toll for anyone.

This park is near the air base that the Japanese took after a 23-hour battle with Australian and Indian forces under the banner of Britain. Next, Zafrani brings me to the outskirts of the Sultan Ismail Petra Airport, formerly the R.A.F. Kota Bharu Airfield. In the distance behind a barbed wire fence is a dark gray, lonesome, perfectly square pillbox about eight feet high with a row of oil palm trees behind it. We can’t get any closer to it, so we ride on. He is intent, and I start to wonder if he might’ve just been messing with me by saying our destination was going to be a bunker.

As we head away from the airport, he tells me he’ll be taking me back here at the end of The Tour so that we can go into the terminal, up to the restaurant level, and I can survey the land where the R.A.F. got walloped and Japan got its foothold in Malaya. Maybe I can even get a little short film playing in my head of a Vickers Vildebeest torpedo bomber biplane or a Brewster Buffalo fighter in flames on the tarmac.

We drive southwest a few miles, then pull a left down a narrow road where a mini-billboard announces in Arabic, Malay, Chinese, Japanese, and, finally, English, only this: Historical Site of World War II. On the left side is a picture of a smiling-but-not-for-long Lt. General Arthur Percival. A Japanese Zero soars triumphantly over his head. At the right is the dour Tiger of Malaya, General Yamashita Hiroyuki, with the halo of Japan’s Imperial Army flag beaming Buddhistically over him.

Something tells me that Malaysia doesn’t care about the war. I went to the National Museum in Kuala Lumpur a few months earlier. The only things that stay with me are certain abysmal silences, as in any material regarding the Japanese brutality which led to the death of over 100,000 Malaysians, and a big gaping nothing concerning the role of Chinese-blooded people in this country’s history, even as 25% of the population is of Chinese descent. Malaysia has a history problem. Zafrani Araffin feels this more acutely than almost anyone here.

We pass the sign that tells us nothing, go down the street a quarter mile, take a right on a dirt road, then stop next to a little yellow house. It was built against the side of a pillbox which now serves as the family’s store room. We get out. Zafrani asks the residents if it’s O.K. for me to take some pictures. They smile in that big charming Southeast Asian way and say sure. I know they can’t imagine my sense of how comical and irreverent the thing is.

We are close to the beach now. The Japanese landed near here. In any Western country, a site like this would be within a historical park. There’d be a sign telling us the meaning of it all. Without which, this pillbox would be a pretty damn ugly stone outhouse or tool shed.

We drive east a short way and cross a narrow one-lane bridge over a shallow muddy river. Along the banks are abandoned car tires and wooden shacks. The Japanese invasion came in the wake of monsoon rains. The river lies between the beach and the airfield. So many bodies clogged this creek after the battle that a boat couldn’t pass for three days.

I ask him about his family. “My mother was living in the village of Kuala Kari just north of here. She was nine when the Japanese attacked. She and her family and neighbors hid in foxholes and kept quiet when the planes flew overhead.” He laughs in his way that’s half embarrassment, half joy. “Even though the planes were high up there, the people were afraid that, if they spoke, they’d be heard by the Japanese.” I want to know how the invaders treated these people: “Some were kind to villagers and led them to safety. Some raped girls and women.”

We drive very slowly under a scattering of coconut trees. Zafrani parks as close as he can to the beach. Walks me over to a miserable plot of ground littered with trash and surrounded by dead palm fronds arrayed to make a fence for the front yard of whoever lives here. There are a few Japanese skulls underground there, he tells me. “Some day, we may dig them up.”

From the skullyard, we walk toward Kuala Pak Amat beach and up to a coconut tree so rotted away, I doubt it'll be here in a year. Zafrani says to me: “We are in the shadows of Pearl Harbor. I'm always sad to come here.” The tree has three holes right through it –- two at gut level, the other neck-high. The vestiges of Nambu machine gun fire in the witching hour on December 8, 1941, Southeast Asia time.

In Pearl Harbor, you can go to the sleek white memorial perched on the water over the carcass of the U.S.S. Arizona. Look down at the hulk of the battleship on which 1177 sailors died that morning. In the middle of the marble wall with the list of all the victims etched in black is a young man whose last name was Necessary. Out on the plank, you stare into the water and see the rainbow-colored oil streaming to the surface from the rusted gun turret. In the Visitors' Center, there's a fine documentary, exhibits, National Park rangers, old vet survivors to talk with.

Hallowed ground. Sanctified turquoise water.

Here, where the war in Asia in fact began, there is this dying, shot-through coconut tree. Zafrani is melancholy. “When this tree is gone, there will be no more relics of the invasion … Very little can be done.” In other words, practically no one in the local, state, or national government gives a damn.

Where we stand now was actually the site of the second wave of the invasion. The first landing site has long since been eaten up by the sea. It's two kilometers out there. And, some ways beyond that, the wreck of the Japanese transport ship, the Awajisan Maru, sent to the bottom by Lockheed Hudson bombers and a Dutch torpedo sub.

We go to the water's edge. Just off to the left, set back a little from the coast, is a row of five ratty wooden huts with orange tin roofs. Pyramidical motel rooms shuttered up years ago. Two seven-year-old boys in yellow shirts drink tamarind juice out of plastic bags and stare blankly at me. I smile at them, say hi, try to make a connection, wonder if they know where they are.

I look northward at this stretch of beach on the South China Sea. As ever, I fail to bring back the dead. I see litter on the coast, but no soldiers. Some people may come to places like this and visualize the landing, the chaos and viciousness, the dead, dying, the gore in the sand. But for me, there's always this failure of the imagination. The projector isn't running.

I ask Zafrani if it's here that he found those cartridges. He blushes and confesses: “Well, I didn't find them. Someone else did and he brought them to me.” If I were a priest, I'd absolve him in a heartbeat for this venial sin. He should write a Kota Bharu invasion novel.

Zafrani and I say goodbye to the little boys and head in the other direction, toward a small, free-standing concrete wall with two fake artillery pieces mounted on top of it and facing the sea, as if to protect the beach from any future attacks. In the center of the wall on the western side is a wooden frame that may have once contained a historical plaque explaining what happened here eight decades ago that changed the world.

But the plaque, like the clock in the Takumi Detachment Memorial tower, is long gone. In its place, a local citizen with more sense of history than most took a can of brown spray paint and wrote

JEPENES

WARS

Adjacent to this wall is a little gazebo where three sullen young teenaged boys smoke cigarettes. The pavilion was apparently put up so that relatives of Japanese soldiers could come and pray for the souls of their dead. Next to this cheap burnt-orange shelter from the sun, and, stranger still, is a faux Chinese structure with six white stone stairs leading up to a viewing stand that's only about 30% covered by a paltry roof. The idea seems to be that visitors with a passion for the past can go up there, look out to the sea, and reflect on the worst war in human history. Or something.

This is how some benighted civic leaders in Kota Bharu decided a few years back to memorialize the outbreak of the Second World War in Asia.

Somewhere out there, on sand that is now the bottom of the sea, Japanese forces hit the ground under fierce fire from British Indian soldiers in the pillboxes and trenches. The beach was mined; barbed wire was strung across it. Over 5,000 men were unloaded from the transport ships Awajisan, Ayatosan, and Sakura. Many of these troops were part of the serial-rape and massacre squads that laid waste to China before Japan got mired there and decided to stake its empire on taking control of the oil and mineral riches of Southeast Asia.

The invaders here at Kuala Pak Amat were mowed down by the score. The lucky ones burrowed ahead with their helmets in the sand, snipping the barbed wire and squiggling over the corpses of their comrades.

Where I stand now with my quixotic new friend was the second line of defense.

Most of the slaughter grounds are submerged. What nature has not claimed, man has neglected. Except for Zafrani and me and a few other dreamers scattered about.

The 3/17th Dogras Regiment let loose a fury to repel the invaders. Part of the Indian Army, they were Punjabi, Madrasi, Hindustani, and Pakistani men in Bombay Bloomers. Under the yoke of England, killing and dying for the empire they would cast off within six years.

We walk away from the smoking teens, the stairway to nowhere, the destitute coconut tree. The gloom that settled over Zafrani lifts as he gets behind the wheel and tells me he's taking me to meet someone not far from here. We zig-zag down a few short dirt roads, away from the beach, and soon stop alongside an old gray wooden house. Zafrani beams like a boy again. “You're going to meet Omar! He was here when the invasion started. You can interview him!”

We walk toward the open door which has an attached stairway leading to the interior. The floor is raised above the ground to keep water and critters out. Nailed to each side of this old three-steps piece is a bright, fading blue plank. Zafrani calls out a greeting. A gentle old man in a kufi cap, loose-fitting cotton shirt, and stylish orange-and-gray-plaid sarong comes out to greet us.

He is Omar Senik, 84, with a slight white mustache, a soul patch, and a goatee. Unique eyes for a Malay –- light blue rings around his big dark pupils. He smiles at us, happy to see Zafrani again and whoever this foreign fellow he has brought along.

As Omar walks down the stairs, his kin appear in the doorway. Three women in headscarves. His wife and two daughters, maybe. Two men in their 30s. A boy about four or five. Omar, Zafrani, and I sit down on little chairs that were once placed behind desks in the local elementary school. One of the younger women brings me a glass of something that looks like Kool-Aid, but it's missing those American heaps of sugar.

Zafrani asks Omar to tell me his story. Pak chik –- this is the local term of respectful address for an elderly man –- Omar is happy to oblige. I wonder if any Westerners have ever sat down with him, if the place we just came from demoralizes him the way it does Zafrani and me.

Omar was a 16-year-old errand boy with the 3/17th Dogras Regiment. About a half hour after midnight on December 8 all those years ago, he was sitting with a squad of 12 Indian Army soldiers, singing a tune in Urdu called “Gana Gao.” He didn't know what the words meant, but he could sing them then and he sings the song for me now. Quietly because he's shy and maybe they sang it that way that night. I listen, enchanted, trying to conjure the scene. A dozen troops from the subcontinent and one teenaged Malay boy singing before hitting the sack. And then came the blasts of artillery fire from Japanese destroyers.

Right after “Gana Gao,” Omar sings part of a song which the conquered all had to chant in Japanese as a welcome whenever the general from the Land of the Rising Sun appeared.

Soon after the first shots were fired, a sentry ran up to where Omar was and shouted: “The Japanese are coming! Run away!” So, he skedaddled to the local mosque. Hearing the initial shooting offshore, villagers thought it was just a training exercise. When Omar got to the mosque, he noticed that the village chief was nowhere to be found. People went looking for him, but he had been captured soon after the Japanese took the beach around 4:00 a.m.

People made dugouts in the sand to protect themselves from the bullets flying everywhere. British planes fired indiscriminately at the ground. Zeros tore in from the South China Sea. Omar heard the Japanese shouting with glee once the Indians were neutralized.

It was a time of drowning. Takumi Detachment troops in the high waves, Indians in the flooded river behind the second line of defense which is now littered with abandoned tires and other trash.

Omar tells me a story which, for some reason, goes into me like a punch. The Japanese had three horses per platoon, some black bicycles, amphibious tanks. The day after they took the beachhead, three of their horses got stuck in the mud near the river. Some local people tried to free them and give them food. The horses wouldn't eat. They just gave up. In a week, they were all dead.

Omar thought he was going to die that first night. He stayed in a dugout for three days, hiding. He had no appetite. Just fear. Like the horses. That thought comes to me and I share it with him. “Yes, like the horses.” And he laughs and I laugh a little, too, but I don't feel quite right chuckling when someone tells me how he lived in a hole for three days expecting to get shot to pieces.

A man named Kawasaki had lived in the village here for over a year. No one had any idea he was a spy. After his comrades sent the British forces running south toward Singapore, Kawasaki gloated: “I'm Japanese. I'm the master now.”

I ask to take some pictures of Pak chik Omar Senik. Maybe one with him. He relaxes with his legs folded. Bare feet. A witness to the outbreak of World War II in Asia. His home is a minute's walk from the front yard of unclaimed skulls.

I ask him to sit on that little flight of stairs with the blue frames. Next to it is a matching blue plastic trash can. He smiles with a trace of mischief and tells me the stairs were taken from what used to be the officers' quarters at the Royal Air Force Kota Bharu Station.

Once the Japanese were in control here, Omar had to work making coconut oil for Japanese forces in China. At bayonet point, he was forced to shimmy up trees and knock down every coconut before descending.

Japan said it was liberating east Asia from the white oppressors. Omar tells me “we had no fabric for clothes, so we just wore gunnysack.”

Anyone identified as having stolen Japanese war materiel was likely to be wrapped in a canvas bag and burned alive. The village chief was ordered to find the culprits. Omar tells me about a 25-year-old man named Jali from nearby Sabah beach. He stole some aircraft fuel and sold it on the black market. Jali was caught and roasted on the upper half of his body, but he survived. Some thieves were buried alive or beheaded. Chandi village was the main place for burying Malays alive. It's now under the sea.

To give me some context, Omar explains that the Japanese buried some of their own severely wounded comrades alive during and shortly after the maelstrom on the beach. A big stone was placed over the spot to mark the grave. But the victors swept south to take the jewel of Singapore. In a front yard of a house near the beach that survives for now are the rotting remains of some who were left behind. Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo has designated each and every one of them kami. Lose your life in the name of the divine emperor and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and you became a god.

At some point after most of the Japanese left Kota Bharu, Omar moved up to Narathiwat, Thailand, where he was more free. “Nobody bothered me there. Some men in the Thai military treated Malays badly, but not as cruelly as the Japanese did.” He stayed in Thailand until the war ended, then came back home.

For about an hour and a half, Zafrani and I sit with Omar and listen to his stories, chat, pass the time. It's getting late in the afternoon; my guide has a few more places to show me. That awkward interval comes when I will say thank you and goodbye and I know I will never see this person again.

Omar has a final anecdote: A few years ago, a young Japanese man visited. He showed Omar a photo of his grandfather. Asked him if he or anyone here might recognize the man. Omar knew right away. It was Kawasaki, the man who pretended for a year to be their polite and friendly neighbor. The spy who proclaimed in the second week of December 1941 that he was the boss now. Yes, Omar remembered him. And he was nice to his descendant. But things come back like haunting dreams that make you get up early in the morning because, if you keep sleeping, it will be unbearable.

Zafrani and I tell Omar and his family how much we appreciate everything. I shake hands with one of the last surviving witnesses of the first battle of what Japanese like to call the Pacific War. I leave him and keep him in my heart. As we drive away, Zafrani asks me, “How was that?!” I tell him he just gave me one of the greatest tours of my life. I don't mention my suspicion that he was messing with me just after 10 this morning when he blandly said he'd show me a pillbox.

After taking me to the airport observation deck so I can try to call forth Vickers Vildebeests and Brewster Buffalos blasted and burning out there on the tarmac, he drives to the only pillbox in Kota Bharu that's marked as a historical site. A low, drab octagon of concrete that I walk into, down a couple stairs so I'm semi-subterranean. I peer out the gun slits at the minarets of an adjacent mosque.

And then it's on to our final destination –- Bank Kerapu, in Malay, the War Memorial Museum for the rest of us. Opened in 1912 as the Mercantile Bank, it's the oldest brick building in Kelantan. During the Japanese occupation, this was the headquarters of the Kempeitai, Hirohito and his generals' Gestapo. This low, two-story, cream-colored structure has the bulk and bravado of an early 20th century bank. Inside, the walls are covered with photos and texts.

It's hardly a great or even a good museum, but it's all this state –- perhaps this nation –- has when it comes to World War II in Malaya. There are copies of good sepia-tone pictures. One of the Awajisan Maru barge before Australian pilots and that sub annihilated it. Another of a wooden sentry hut at the airfield when it was the R.A.F.'s. The big sign in front of the gate makes it clear that entry was by PERMIT ONLY and that all the men had to BEWARE OF APPROACHING AIRCRAFT. But Britain wasn't ready in this part of its empire.

One panel has curiously faded text about Emperor Hirohito. I squint to make it out. The living-deity monarch and Supreme Commander of Japan's military was, according to whoever decided to tell the stories that this museum tells, “a mild and ineffectual man, more interested in marine biology than in matters of the state … He left those matters to Tojo, and merely assented to the militarists.” I tell Zafrani that nothing could be further from the truth. He shrugs. This museum is perpetrating exactly the same myth which prevails in Japan. The essential benevolence of his majesty must not be called into question. Not even here in Malaysia.

When I finish spending my typically inordinate amount of time in the museum, I know that the time for Zafrani and I to part has come. He told me earlier that he'd have to get back home about 5:00. Outside the old central office of Japan's secret military police, I give my most heartfelt thank-you to this kind man, Zafrani the history buff who pays the bills by working in what I imagine to be a mind-numbing bank job.

I think of him as a kind of soul brother. And I tell him that, if there's anything I can ever do for him to repay his kindness, I'll be glad to. He smiles in his charming way and says, “Oh no. My pleasure. It was great to meet you.” And then he gives it another thought. “Well, there is one favor you can do for me. On your way back to Phuket, can you stop in Pattani and Songkhla and take photos of Japanese invasion sites in those provinces? It's too dangerous there! I don't want to get killed!!”

He laughs in his lovable way; there's no irony to it. Pattani is under martial law. Tanks routinely roll down the streets in the city. Terrorist attacks are common enough that they don't get much attention in the national news.

“Sure!” is what I say to my new buddy. And surely, I will go there. I don't value my life so dearly that I won't risk it to find and photograph places in Thailand's deep south where the Japanese invaded and Thai soldiers put up a good fight for one day before the dictator Phibun in Bangkok made peace with Tokyo.

No no. My life is not that precious. Just ask Zafrani.