Newsboys in antebellum New York and elsewhere were embroiled in all the major conflicts of their day, becoming mixed metaphors for enterprise and annoyance.

-

Winter 2021

Volume66Issue1

Editor's Note: Vincent DiGirolamo is a professor of history at Baruch College in New York City. This essay is adapted from his most recent book, Crying the News: A History of America's Newsboys (Oxford University Press), which won the 2020 Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians, among others.

“To see a News Boy in all his glory, you must get up an hour before day break,” advised the New York Sunday Morning Atlas in 1840. “Direct your steps towards one of those profitable establishments called a cash paper. As you near it you will hear the hum of many voices, mixed with a deep bass rattling sound, to which they play a sort of falsetto. You come to the office and you are suddenly in the midst of a troop of Lilliputians. A number of them are gazing anxiously down a cellar from which a considerable quantity of steam ascends, through which steam appear several twinkling lights like stars in a fog.”

So begins one of the first journalistic descents into the world of the newsboy. It was a noisy, subterranean world shrouded in vapor, cloaked with romance, and now blurred by the mists of time. Our guide remains a mystery as well, perhaps one of the paper’s three proprietors or an anonymous penny-a-liner who labored under flickering gaslight on the margins of fame and penury.

Yet his reporting enables us to see and hear with astonishing clarity how a new occupational group came of age in “Young America” and became its principal symbol, embodying the exuberance and possibility of a republic that had survived its revolutionary infancy and was about to enter the next glorious stage of its national life.

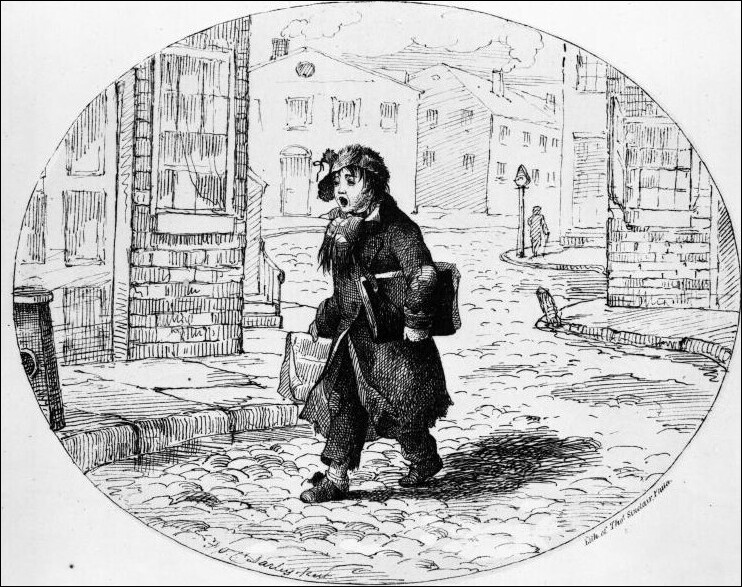

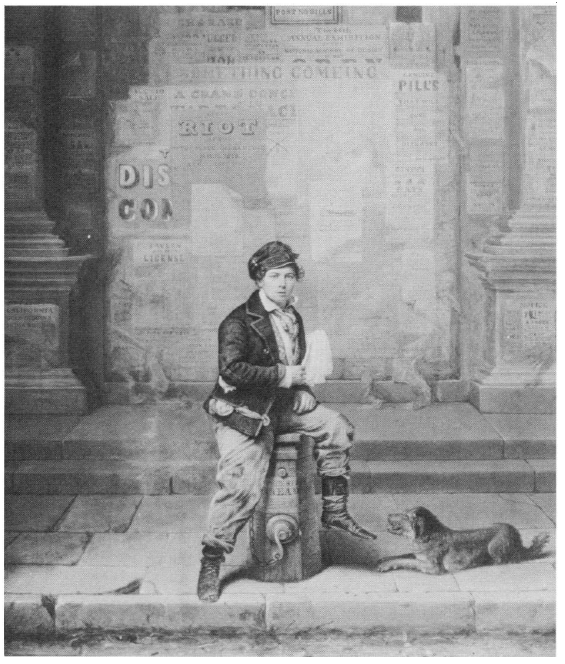

In the seven years since they first flogged their papers on the streets of New York, newsboys had cropped up in most American cities and formed one of the nation’s first urban youth subcultures. Their castoff clothing, unintelligible slang, and adolescent swagger alerted all who saw and heard them that they were lads who knew the tricks of their trade and the ways of the world. “Nature seems to have contemplated a peculiar race of juveniles expressly to become Newsboys!” mused one natural philosopher.

To make good on his promise to “show the News Boy up in all his peculiarities,” the Atlas man had to go no farther than his own office. As the newspaper’s powerful presses rattled and belched in the cellar, he took in the scene. He saw several boys “indulging in a snooze” and noted that when the weather was fine “youthful snorers” could be heard occupying all the empty boxes and casks nearby. A man shouldering several quires of newspapers suddenly emerged from the steamy cellar, followed by a helper. As they stepped into an office, a shout rang out and in rushed the boys who had been watching from atop the stairs. “A hundred or more boys are assembled and each is struggling and striving to get served first, as though his life depended upon it. This is considered an important point . . . [as] the earliest sellers reap the richest harvest.”

As soon as they got their papers, the boys ran off toward the piers and markets, filling the air with their cries: “’Ere’s the Sunday Morning Atlas!”

In describing this weekly ritual, the Atlas writer highlighted many important aspects of the trade. The invention of steam presses in the 1830s had made newspapers one of the first modern mass-produced commodities, yet their distribution required a host of Old World hawkers and carriers, mostly children. He conveyed the scale of this trade when he noted that the Atlas, which had a circulation of 3,500, or about 20 percent of the output of the city’s five Sunday papers, relied on more than a hundred newsboys. He touched on the industry’s obsession with speed, which was fast becoming a moral imperative in the cosmology of modern journalism. And he attested to the relative autonomy of the boys and the boisterous blend of competition and cooperation that characterized their work.

But who were these boys, really? To answer the question, America’s most celebrated writers, artists, and entertainers produced a carnival of works that promised, like the Atlas, “to expose the true character of the newsboy.” What their efforts reveal is that the newsboy was himself a product of popular culture and mass politics whose insistent adolescent voice struck the keynote of the era.

America at midcentury was distinguished by one indisputable demographic fact: children outnumbered adults. According to the 1850 US Census, 52 percent of the nation’s population was under the age of 19; 41 percent was under 15. Newsboys made up a small but growing proportion of this cohort. Their numbers rose right along with the number and circulation of America’s newspapers. Nationally, 116 dailies sprang up in the 1840s. Another 133 were founded over the next decade, culminating in 387 in 1860.

This expansion was most apparent in New York, whose fourteen to eighteen dailies emitted 60,000 copies by 1840 and rose to 300,000 by 1860. Several popular weeklies boosted this output: the New York Ledger (founded in 1851), Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1855), and Harper’s Weekly (1856). Altogether, counting weeklies and semiweeklies, Gotham’s 104 newspapers claimed (and probably attained) a yearly circulation of 78 million, followed by Boston, whose 113 papers produced 54 million copies, and Philadelphia, whose 51 papers turned out 40 million.

These publications circulated via news agencies and the mail but also by newsboys. In 1842 New York’s weekly Flash estimated there were “some three hundred in the city, perhaps more.” The Herald alone claimed 150 newsboys and carriers of all ages. In 1852 the Clipper counted “thousands of men, women, and children engaged in the retail newspaper trade in New York.” Of these, between 500 and 600 were boys. The New York State Census of 1855 offered the least reliable head count, listing newsboys (probably adults only) among the 388 people engaged in “miscellaneous occupations.”

By 1860 more than half of the city’s population was foreign born. Their children, who “seemed to spring, mushroom fashion, out of the very ground,” provided an ample labor pool for the burgeoning news trade. A visiting Scotsman noted the dominance of the Irish: “Ragged, barefoot, and pertinacious, they are to be found in the streets from dawn till past dark, crying out ‘The glorious news of the fall of Delhi!’ The last ‘terrible explosion on the Ohio—one hundred lives lost!’ or the last ‘Attempted assassination in a lager beer cellar!’ They recall the memories of the old country by their garb, appearance, and accent, if not by their profession.”

Newsboys ranged in age from 6 to 16, but in 1842 the strolling newspaper columnist Lydia Maria Child found “a little ragged urchin, about four years old, with a heap of newspapers, ‘more big as he could carry,’ under his little arm, and another clenched in his small, red fist. The sweet voice of childhood was prematurely cracked into shrillness, by screaming street cries, at the top of his lungs: and he looked blue, cold, and disconsolate. May the angels guard him!” The Clipper also spotted newsboys as young as 5 and 6, and admitted that some were probably sent out by drunken parents to earn money for liquor.

According to the Flash, newsboys came in two grades: speculators and worker bees. The speculators were erstwhile newsboys who had risen to become wholesale dealers or agents. Also known as “Chief Newsboys,” “Foremen,” and “small Capitalists,” these middlemen helped newspapers reach boys throughout the city. Far outnumbering the speculators were the worker bees. “Some of them are the children of poor parents, forced into their occupation by privation and suffering, and they gain more by it on an average than grown men can by manual labor,” said the Flash.

New York’s worker bees bumbled their sheets wherever customers could be found. They swarmed around City Hall, the courthouse, and other public buildings. So many “vagabond newsboys and peddlers” lined the halls of the post office and filled it with their “vile and disgraceful language” in the winter of 1840 that a Masonic newspaper recommended they all be horsewhipped, an idea no doubt appalling to Lydia Maria Child.

Still, they persisted, and sales increased every year. Their customers were not just merchants but workers as well, a fact often remarked on by visitors. “Newspapers are seen everywhere in the hands of the labouring as well as the wealthy classes,” noted another Scotsman in 1854. “In the streets, at the doors of hotels, and in railway-cars, boys are seen selling them in considerable numbers. Nobody ever seems to grudge buying a paper.”

Whichever kind of paper they sold, newsboys relied first and foremost on their voices. Two good legs were a luxury in a trade so amenable to the disabled. A cocked eye or humped back could boost business by generating sympathy. But a newsboy with weak pipes was a hopeless case. He risked losing his livelihood if he lost his voice and, according to writer Cornelius Mathews, might be considered “as pitiful as a bill sticker.”

In between their cries, newsboys communicated with each other in what sounded to many like a secret language. Some traced it to the boys’ propensity for abbreviation or their absorption of all the catchphrases of the theater and the penny press, particularly insults (“Does your mother know you’re out?”) and thinly veiled threats (“Some things can be done as well as others”). Newsboys were notoriously insolent. “He opens his mouth,” said George D. Strong of Knickerbocker

Magazine, “and out flies a winged army of proverbs calculated to ridicule wealth, and contemn station.”

Next to their voices, newsboys were most distinguished by their appearance, which was at once flamboyant and ragtag. “In his dress,” wrote journalist George G. Foster, “he does not affect the latest fashions.—No Newsboy, no legitimate Newsboy, has ever been seen in a whole suit. The uniform of his Craft is a slouched cloth cap, dilapidated roundabout and breeches, no shoes or stockings, and a dirty face with hands to match.”

Together, their walk, talk, and dress constituted the outer signs of an inner quality or attitude, which could be summed up in a word: “sauciness.” It was this attitude, along with his voice, that enabled the newsboy to seize public space.

What some saw as spirit and independence, others regarded as aggression and criminality. Violence was endemic to working-class life. All boys fought to settle differences, to prove their manhood, or just for fun. But such conflicts were more intense with economic interests at stake. Fighting, in short, was part of a newsboy’s job; he had to fight to protect his turf, his stock, his earnings, and his honor. In 1843 a New York newsboy invoked his rights as a citizen by driving off a larger competitor from his hydrant on the corner of Pearl and Chatham Streets: “I don’t like to hurt not no one a mite,” he said, “but this is the U-nited States, and Bob Morris is mayor.”

The petty thievery practiced by newsboys occurred in an industry rife with chicanery. Hoaxes continued to entertain and exasperate the public. In March 1841, newsboys in Boston busily sold copies of President Harrison’s inaugural address until it was discovered to be Thomas Jefferson’s speech, to which had been affixed Harrison’s signature. And in April 1844 they profited from a hoax perpetrated by Edgar Allan Poe in the ever-receptive Sun. Poe fabricated a three-day crossing of the Atlantic by a balloonist. “I never witnessed more intense excitement to get possession of a newspaper,” he bragged.

Given the ebb and flow of sales, scams, and sidelines, newsboys’ incomes varied greatly. The Brooklyn Eagle said its boys typically earned 3 or 4 shillings (35¢ to 50¢) a day. Cries of New York reported 30¢ as the low end of the scale but said some boys made $1 profit on each hundred sold. Apparently these earnings did not suffice, as newsboys accounted for 40 to 50 percent of all minors arrested for theft in New York in the late 1840s.

More than any other personification of the age, the newsboy represented the liberating potential of a democratic society driven by a wide-open market economy. In the capable hands of Young America’s cleverest writers, artists, and actors, newsboys elbowed their way into political and cultural debates over the relative influence of class or character in shaping individual and national destinies.