The sitcom “All in the Family” debuted 50 years ago this month, and had a lasting effect on television and American culture.

-

Winter 2021

Volume66Issue1

Editor’s Note: Jim Cullen holds masters and PhD degrees in American Studies from Brown and the author of over a dozen books. For the following essay, he adapted portions of his new book, Those Were the Days: Why All in the Family Still Matters (Rutgers University Press), the definitive history of the landmark show.

Fifty years ago this month, on January 12, 1971, All in the Family made its debut on national television. The idea of a TV show — a comedic one, no less — featuring a bitterly divided family arguing about so many taboo subjects was radical. Archie Bunker and his children squabbled over politics, racism, antisemitism, religion, infidelity, homosexuality, women's issues, and the Vietnam War. There had never been anything like it.

Yet the program became wildly popular, often reaching weekly audiences of 50 million viewers. Running for nine seasons and 205 episodes, All in the Family won or was nominated for an astonishing 56 Primetime Emmy awards and 29 Golden Globes.

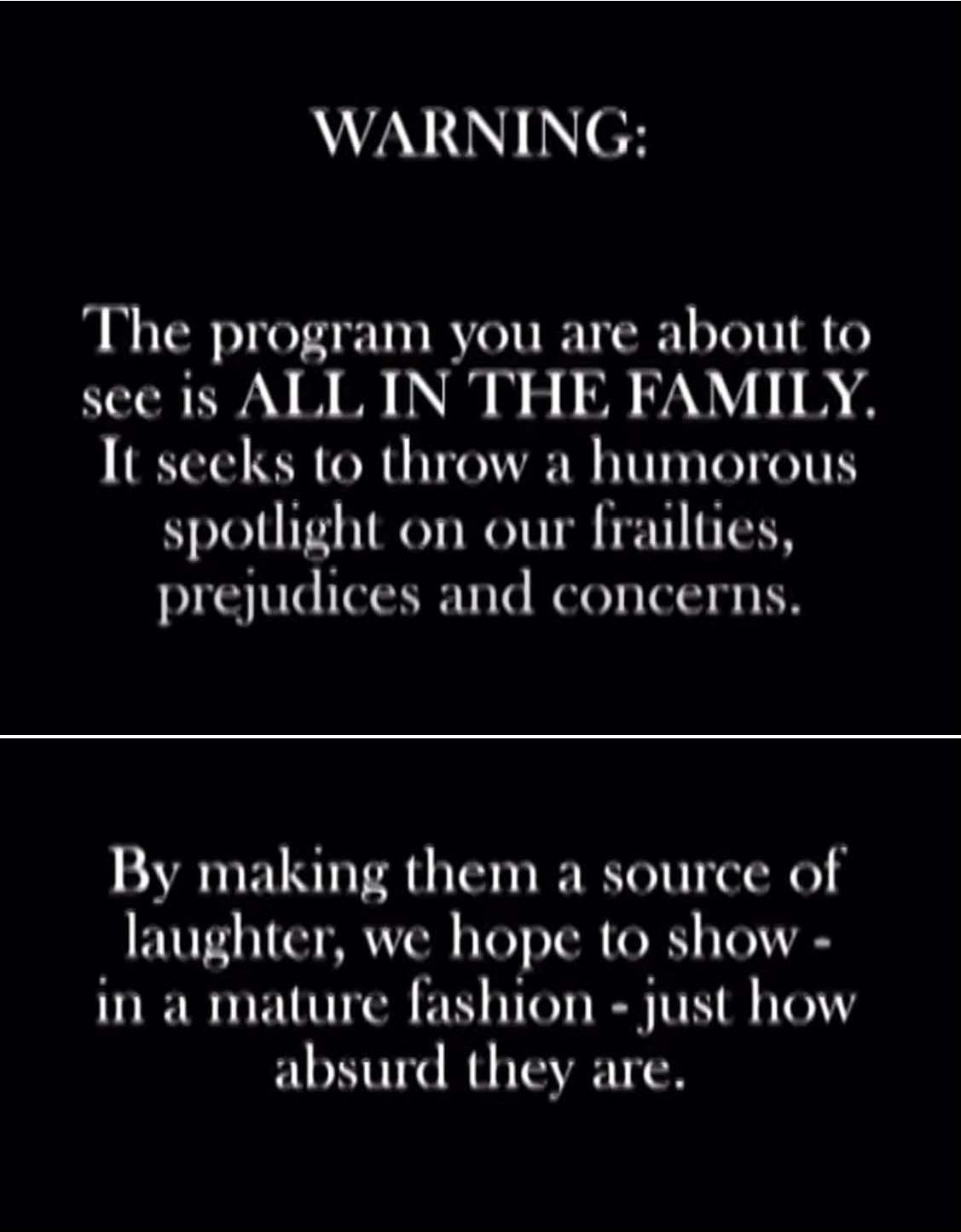

CBS executives insisted on placing a warning before the first episode, “Meet the Bunkers,” because it included so many words that audiences had never heard on television before that. “The network thought that with the first show it would be advisable to put in an advisory that there would be controversial material discussed here. So careful,” recalls Norman Lear, the show’s creator.

The showed opened with Archie and his devoted wife Edith singing the theme song. “Boy the way Glen Miller played, Songs that made the hit parade, Guys like us we had it made, Those were the days.”

But shortly after, Archie and his son-in-law Mike “Meathead” Stivic get into an argument about race, with Archie insisting. “If your spics and your spades want their rightful share of the American dream, let ‘em get out there and hustle for it just like I did,” insists Bunker.

“Now I suppose you’re going to tell me the black man has had the same opportunity in this country as you,” counters his son-in-law.

“More. He’s had more,” says Archie. “I didn’t have no million people out there marchin’ and protestin’ to get my job.”

“No,” interjects Archie’s loving but long-suffering wife Edith. “His uncle got it for him.” As often happened in the show, a bit of humor tempered the situation.

All in the Family has lived on in collective memory as one of the best shows of its kind — the situation-comedy, or sitcom. It bears a genealogical resemblance to ancestors such as The Honeymooners (1955–1956) and I Love Lucy (1951–1957) in its manic energy and engagement with racial and class issues. It also exhibits traits that can be seen in many heirs. Married . . . with Children (1987–1997) inherited its penchant for depicting family conflict; The Simpsons (1989–) and South Park (1997–) carried forward its daring irreverence. One could cite many other examples. But no show has combined these elements quite as effectively as All in the Family did.

A great many informed observers consider the creator of All in the Family, Norman Lear, as central to the history of the genre. “The way I look at it, television can be broken into two parts: B.N. and A.N.: Before Norman and After Norman,” says Phil Rosenthal, creator of the highly successful sitcom Everybody Loves Raymond (1996–2005). “He’s the most influential producer in the history of television because of this gigantic change that happened when All in the Family hit the air.”

The “gigantic change” that Rosenthal refers to is in the themes, topics, and ideas presented on All in the Family, many of which were unprecedented. Before it came along, the sitcom was a highly stylized kind of TV show with clear boundaries of form as well as content. An early historian of television, Horace Newcomb, observed that the sitcom, “will fall into four basic parts: the establishment of the ‘situation,’ the complication, the confusion that ensues, and the alleviation of the complication.” (One can still see this pattern in most sitcoms to this day.) “The essential factor is the remedying of the confusion. It is rather like a mathematical process, the removal of parentheses within parentheses.”

As Newcomb realized, All in the Family revised this formula. To be sure, it maintained many core elements of the sitcom, especially in terms of its structure — which was surprisingly traditional. But the show pushed boundaries in all kinds of ways, among them its willingness to use profanity, engage taboo topics, and offer ambiguous, even disturbing, endings. Admittedly, it didn’t explode the conventions of the sitcom — true to form, its protagonist was a bigot, but not a malicious one — and it purveyed ideas that were daring in its time but can seem dated, even lame, today. And yet the show still maintains its power to shock, whether in depicting a frightening rape or a character unselfconsciously uttering hate speech.

All in the Family has also stood a test of time for its quality: the writing, the acting, production design, and camera work remain impressive a half century later and have engendered durable affection. So it is, for example, that the twenty-first-century comedian Amy Poehler, who called All in the Family “the best show ever,” has indicated that she named her son Archie in honor of the protagonist.

Over the half century, Norman Lear has emerged as a pioneering figure in the history of broadcast television, a maverick who broke countless taboos. But he was very much a product of the medium and had been present at its creation. Lear was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on July 22, 1922, to a Jewish family whose members lived, as he liked to say, “at the ends of their nerves and the top of their lungs.” Lear’s father, Herman, served a three-year prison term for fraud when Norman was a child, and periodic financial upheaval was part of his early life, which was also marked by frequent strife between his parents — his memories include his father’s frequent demand that his wife “stifle herself,” a term that would later become part of Archie Bunker’s verbal repertoire.

Lear has repeatedly noted that Archie’s character was indeed modeled on his father Herman — like Archie, he ruled his roost from a beloved armchair and would resort to casual bigotry in describing his son as “the laziest white kid he ever met,” a line that would make it into the pilot episode of the series — but his memoir makes clear that the Lear family was one of pronounced striving for upward mobility, albeit in ways that crossed ethical lines.

Lear’s moral fervor was heightened by the crisis of the 1930s, and in particular his experience as a Jewish boy in an age of rampant anti-Semitism. He describes listening to the radio broadcasts of famed “Radio Priest” Father Charles Coughlin, which were filled with hate-filled invective against Jews. When World War II broke out, Lear was eager to join the fight. “I wanted to be known as a Jew who served,” he explained. “I wanted to bomb, I wanted to kill.” He served in the Air Force during World War II as a radio operator on B-17s, flying dozens of missions over Germany in 1944-45. On some of those missions, his bomber was protected by fighter planes manned by the famed Tuskegee Airmen, a cadre of elite African American pilots, an experience that appears to have influenced Lear’s subsequent racial attitudes.

After the war, Lear joined the masses of Americans who sought to claim the fruits of victory. He married for the first of three times, fathered the first of his six children, and worked briefly as a press agent and for his father in a failed appliance company. Yet his restlessness, ambition, and talent were distinctive. Hankering for a career in show business, Lear set out for Hollywood, where he hooked up with his cousin’s husband, Ed Simmons.

Through a combination of luck and persistence, they landed a series of gigs writing material for comedians, notably Danny Thomas (himself a broadcast pioneer). This in turn led to invitations to write for television, among them for the hottest act in entertainment in the early 1950s: Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.

By the mid-1950s, Lear and Simmons had become among the best-known and highest-paid writers in the business, though that business was also one of big paydays followed by anxiety-inducing layoffs. The two would eventually strike out on their own, and Lear began collaborating with a series of other showbiz people, among them the director Bud Yorkin, with whom he would form an outfit they dubbed Tandem Productions. The duo would share a series of duties in developing projects, but Lear was typically a writer/producer and Yorkin a director. As such, they went on to make a number of television shows and movies, among them the 1964 Frank Sinatra vehicle Come Blow Your Horn.

Until this point in his career, there was little evidence that Lear saw himself as a maverick. To be sure, he was very aware of his minority status as a Jew, one that shaped his sense of himself even in an entertainment business that had plenty of them. He grew up imbibing the talents of Jewish comic radio giants such as Eddie Cantor, Jack Benny, Fred Allen, and George Burns (whose comic sidekick was his Catholic wife, Gracie Allen).

As a student at Emerson College in Boston during the early 1940s, Lear regularly visited burlesque shows, a working-class form of entertainment with strong sexual overtones that included striptease. He later described burlesque as “my acting, producing, directing, and casting school,” and it furnished the basis for the hit 1968 movie The Night They Raided Minsky’s, which he co-wrote and produced.

Such formative entertainment experiences shaped Lear’s earthy sense of humor, but not an especially critical one. He came of age in an era of assimilation; as he noted of his wartime service in 2014, “We were far more in love with America and far more connected to the idea of America than we are now.” One needs only a few moments in reading an interview with Lear or hearing him talk to experience his sunny disposition; a sense of optimism seems to have buoyed him throughout his career and animated a sense of personal as well as collective progress.

Around 1967, Yorkin was living in London and brought a British show to Lear’s attention, an episode of a BBC anthology series, Till Death Us Do Part, about a working-class character named Alf Garnett, his weary wife Else, and their daughter Rita. Alf held reactionary views and clashed with his son-in-law, a staunch socialist lacking much in the way of a work ethic. Larry Gelbart (the writer and producer who would later go on to produce M*A*S*H) also lived in London at the time and was similarly fascinated. “You didn’t watch it; you were riveted to it,” he recalled. But both Yorkin and Gelbart were skeptical it could translate to the U.S. Gelbart observed the BBC show showed “what happens when you don’t have to worry about the terrible two A’s: affiliates and advertising.”

But Lear saw possibilities — and seized them. “Oh my God, my dad and me,” he later said about Alf and his son. “I was flooded with ideas and knew I had to do an American version of the show.” Lear would later enumerate his own ideas for the characters: “I wanted him to have far more humanity [than Alf ]. I wanted him to have a daughter, and I wanted the daughter to love her dad. I wanted his wife to love him, whoever he was, whatever he was.”

But Lear’s social conscience was there, waiting to be tapped. In later reconstructing his interest in African American life, for example, he described taking trains from Hartford to Manhattan as a child, gazing at apartments in Harlem and picturing the lives of its residents, as well as recalling his wartime sense of shame at the way black GIs were treated in a segregated army. As a young man he regularly shot off telegrams to members of Congress.

Yet until the late 1960s, this sensibility wasn’t reflected in his work. “I’ve wondered why the political activist in me took four decades to fully surface,” Lear reflected toward the end of his life. “I think it had something to do with money. Not dollars per se, but the feeling of comfort and safety that flows from acquiring enough of them.” A series of factors had come together by then: Lear had achieved financial security; the nation was undergoing dramatic changes; and a bold move could bolster his career. These elements coalesced when he seized on a television project that captured his imagination.