Adding Republicans to key positions in his administration, Franklin Roosevelt created a unified effort to fight World War II.

-

November/December 2022

Volume68Issue6

Editor’s Note: Peter Shinkle worked for two decades for various news organizations, including, most recently, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. We asked him to provide an overview of his most recent book, Uniting America: How FDR and Henry Stimson Brought Democrats and Republicans Together to Win World War II, which looks at the under-appreciated importance of bipartisanship during World War II.

After tearing through Belgium, the Netherlands and France, Adolf Hitler’s armies had surrounded British and allied troops at Dunkirk in early June 1940. Fearing Germany would attack Great Britain next, Prime Minister Winston Churchill appealed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt for arms to help the British could defend themselves from Nazi fascism.

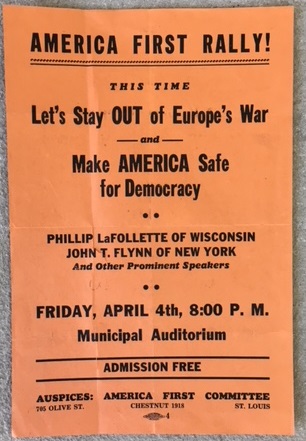

In America, however, isolationists bitterly condemned FDR, accusing him of dragging the United States into another costly European war. On June 3, Representative Hamilton Fish, a New York Republican and ardent isolationist, took the floor of the House of Representatives and hurled a rhetorical bomb, suggesting that Democrats were encouraging FDR to “set up a dictatorial government in the United States.”

Amid a drumbeat of attacks on FDR’s war policies, the Republican Party prepared to select a presidential nominee at its national convention in Philadelphia in late June 1940. If a staunch isolationist won the election that fall, America might refuse to send aid to any allies; the prospect of a Nazi empire spanning all of Europe loomed.

On June 20, 1940, FDR launched a bold strategy to undercut the isolationists. In a surprise announcement, he appointed two prominent Republicans — both strong supporters of aiding America’s European allies — to critical posts in his cabinet. Henry L. Stimson, who had been secretary of state under FDR’s Republican predecessor, President Herbert Hoover, would be Secretary of War, and Frank Knox, the Republican vice-presidential nominee in 1936, would be Secretary of the Navy. The White House said the appointments, setting partisan politics aside in the name of defending the country, were intended to create “national solidarity.”

By their example, Stimson and Knox encouraged other Republicans to support the Democratic president. The appointments immediately set off an uproar among Republicans. On the day of FDR’s announcement, Republicans lambasted Stimson and Knox at their national convention. They were, some said, “read out” of the party and no longer spoke for it. Yet days later, in a stunning turnaround, the convention rejected the leading isolationist candidate and instead chose Wendell Willkie, whose war policy was closest to FDR’s, as the party’s 1940 presidential nominee.

The Stimson and Knox appointments were a daring and risky move that placed a bipartisan political relationship at the very center of America’s defense against fascism. The gamble paid off. Stimson and Knox cultivated an appearance of nonpartisan leadership, and their support ultimately helped FDR win the 1940 presidential election. The Nation’s Capital gained a new spirit of solidarity, and many bills passed Congress over the next five years, with strong backing from both parties. The bipartisan coalition worked effectively to unite the nation, rapidly expand and strengthen the American military, and secure victory in World War II.

Stimson, despite his relatively advanced age — he accepted FDR’s appointment at age seventy-two — spearheaded the bipartisan alliance and carried it through the end of the war. Other prominent Republicans soon joined forces with FDR, including his recent opponent Willkie, New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia, and William Donovan, who was appointed to lead the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime spy agency. Each of these men chose to stand with FDR to defend democracy at a time when doing so meant losing favor with large numbers of Republicans.

See also “The Day When We Almost Lost the Army”

by Joseph E. Persico

The alliance was in full swing long before the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor spurred the nation to widely support the war effort and abandon isolationism. It arose at a time when isolationists held sway in Congress and had blocked preparations for war — a time when it was not easy for Republicans to side with the Democratic president. Yet even after Pearl Harbor, FDR found significant benefits in bipartisanship and sought to work with more Republicans as the war went on. He even imagined a future in which liberals in the Republican Party would convert to the Democratic Party, which would in turn send its conservatives over to the Republicans.

This embrace of bipartisanship as Hitler’s war machine savaged Western Europe was instrumental in leading America and its allies to victory in World War II. Yet it has been all but forgotten. One reason for this national amnesia is that FDR and Stimson were so skilled at creating unity that their party differences faded into the background. Another is that political partisans typically attract adherents and campaign contributions by demonizing opponents as irrational and intransigent — not by celebrating shared goals achieved through collaboration with opposing parties. There is an old saying that success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan. To this one might add: compromise, even for the national good, is a neglected child.

In fact, there was something of a Republican brigade in command of the War Department under FDR’s Democratic administration. Stimson’s diary, an authoritative contemporaneous account often cited by historians, has never really been mined for a picture of his wartime collaboration with FDR. My research uncovered a remarkable letter in which Stimson considered becoming secretary of war to take the War Department as a “hostage” of the Republican Party.

The FDR-Stimson alliance was informal — it had no founding charter, no written agreement. It also expanded beyond FDR to include First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and cabinet members like Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. The two major parties still dominated politics in Washington, and partisan disputes — even very acrimonious ones — still arose, yet they did so against a backdrop of leadership in the White House that aimed for bipartisan agreement.

Today, it may seem a matter of course that — at a time when the nation’s existence was threatened — Republicans and Democrats would set aside partisan disputes and work together. But it was never a matter of course. A lifelong Republican, Stimson had publicly criticized Roosevelt, and many Republicans denounced his acceptance of the post of secretary of war. On the other side, FDR had fought innumerable battles with Republicans during his long career. He may have been able to secure more wavering Democratic voters in 1940 by appointing a prominent Democrat.

Stimson and FDR, both students of history and admirers of President Abraham Lincoln, surely knew of the pitfalls of bipartisanship revealed by events seventy-five years earlier. Lincoln, the heroic Republican, sought to build a spirit of national unity in the midst of the Civil War by choosing a pro-Union Democrat, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, to be his vice-presidential running mate. They won the 1864 election. After the war ended the next year, of course, Lincoln was assassinated and Johnson became president. The new Democratic president eventually fired his Republican secretary of war, Edwin Stanton — causing a storm of protests among Republicans.

Republicans in the House of Representatives impeached Johnson over Stanton’s firing; although the Senate acquitted Johnson, the party divide that Lincoln had hoped to close grew wider again. This was a searing cautionary tale of the risks of bipartisan control of the executive branch. Nonetheless, three-quarters of a century later, a Democratic president and a Republican secretary of war chose the path of bipartisanship in an effort to unite America. This was neither an obvious choice nor a preordained one; it was a courageous decision by both men that ran contrary to partisan pressures, political convenience, and the lessons of history.

Over nearly five years of war, Roosevelt and Stimson worked together over hotly contested matters such as initiating a military draft, invading North Africa and a long dispute with Churchill over whether to invade Nazi-occupied France. Sometimes, their work was amicable, and sometimes it was marked by anger and discord, but their relationship — underlain by a bond of trust — only grew stronger through the years.

Ultimately, as FDR wrote his friend in November 1944, “we both have faith and that is half the battle.” FDR and Stimson also struggled with issues for which they are widely and correctly faulted — their refusal to desegregate the armed forces even as Black soldiers fought and gave their lives to preserve America’s freedom, their internment of Japanese-Americans and their sometimes-halting response to the Nazi genocide of European Jews and other groups.

After FDR’s death in April 1945, Stimson continued his collaboration with Democrats by working closely with FDR’s successor, Harry Truman. The relationship faltered when Truman diminished Stimson’s role in the decision to drop the atomic bomb, but Truman ultimately embraced bipartisanship in creating the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to defend democracy.

Just as it was in 1940, the United States is once again riven by extreme partisanship. And once again, in America and elsewhere around the world, democracy faces enormous threats. The compelling story of the bipartisan wartime alliance, marked by both brilliant achievements and haunting failures, should inspire those who have hopes of uniting America today.

Adapted from UNITING AMERICA by Peter Shinkle. Copyright (C) 2022 by Peter Shinkle. Shared with the permission of St. Martin's Publishing Group.