From Henry Clay to Barry Goldwater and Shirley Chisholm, our failed presidential contenders can still inspire us with their legacies.

-

November/December 2022

Volume68Issue6

It is uncommon for American presidents to have their post-presidency pronouncements remembered. Yet the most oft-quoted words spoken by Theodore Roosevelt come from a speech he gave after he left office. In 1910, after completing a safari in Africa, Roosevelt had been invited to speak at the Sorbonne. The speech included a passage that has been quoted and cited widely in the century that followed.

This has become known as the Man in the Arena passage. Less commonly known is the title of the speech from which it is taken, which is “Citizenship in a Republic.” One of the key themes of Roosevelt’s speech was that modern republics like France and the United States require a different sort of citizenry than the types found in countries with authoritarian systems. Republics, by contrast, need a more active, determined people: “The good citizen in a republic,” Roosevelt declaimed,” “must first of all be able to hold his own. He is no good citizen, unless he has the ability which will make him work hard and which at need will make him fight hard.”

Roosevelt’s conception of the active life entailed more than strenuous effort. It also involves a capacity for productive struggle and competition in which risks have to be faced and accepted. To pursue victory is to accept the possibility of defeat—and not be deterred by it. Entering into the arena could no longer be reserved for the elite champions. Roosevelt understood that the success of the American experiment needed a people undaunted by great challenges. That, in turn, requires a culture that honors those who take great risks, even if they fail.

In America, we have an appreciation for entrepreneurs and the risks they take with new ventures. Success in business is almost always accompanied by various failures and setbacks. We celebrate figures like Steve Jobs who was driven out of the company he founded, only to learn from his mistakes and return to it with a greater ability to lead.

The one area where our appreciation of risk-takers seems to lag is presidential elections. Rather than celebrate those figures determined enough to contend for the highest office in the land (even at the risk of conspicuous failure), Americans quickly forget these individuals, preferring instead to focus solely on the winners. In doing so, we deprive ourselves of the inspiration that can be drawn from the legacies left by these contenders. Here are some illustrations of that point:

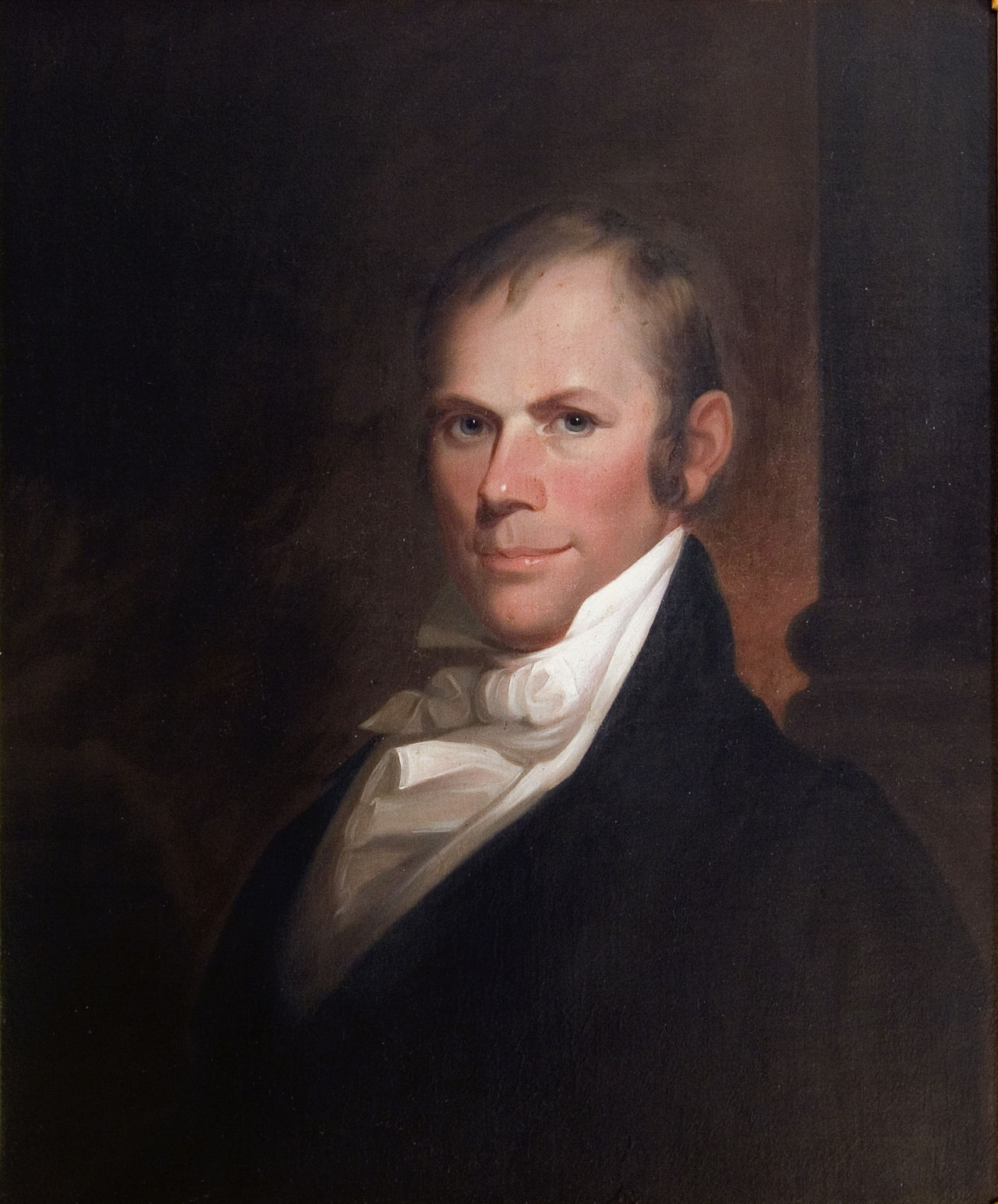

Henry Clay

As I noted in In the Arena: A History of American Presidential Hopefuls, Americans tend to celebrate the founders of our republic, while overlooking the generation that followed and which was tasked with taking the constitutional blueprints left by their predecessors and creating a sustainable, self-governing nation. Henry Clay was one of the towering figures in the first few decades of our history. His work as a leader in Congress helped set the precedents which created an effective, functioning political culture. He took the role of Speaker of the House of Representatives and made what had been a largely ceremonial role into a potent political position, and eventually came to be venerated by generations of American politicians. (Abraham Lincoln was among those leaders who saw Clay as someone to emulate.)

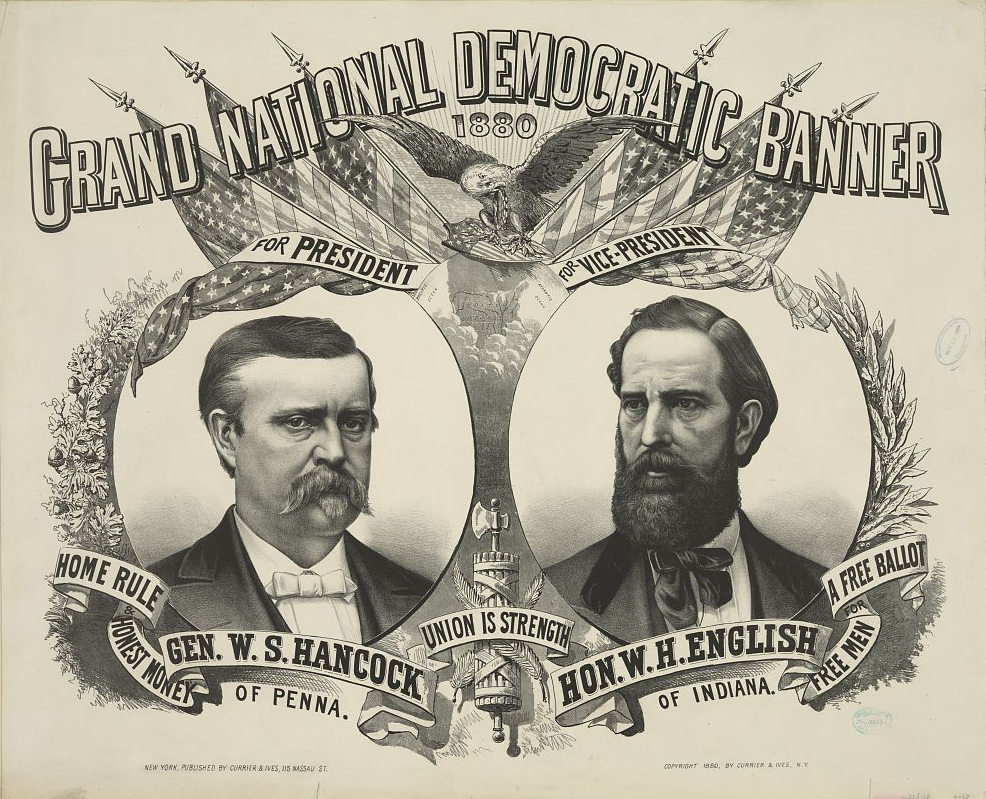

W.S. Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock was the only American presidential candidate who could boast of having been a commander in the Battle of Gettysburg (where he was wounded). Before the Civil War, Hancock served in military posts throughout the country, including Florida, Missouri, Minnesota and California—which gave him the opportunity to observe almost every region of the country outside of the original thirteen states, a rare experience in the days when the railroad was in its infancy.

Hancock was esteemed even by those who opposed him. His friendship with Lewis Armistead, a confederate general who had served with him before the Civil War, provides one of the more moving subplots of the film, Gettysburg. After the war, Hancock distinguished himself as military administrator with authority over Louisiana and Texas. He emphasized that the hand of the military should be as light as possible, accompanied by the re-establishment of civil institutions such as a free press. In a general order, Hancock justified his stance by insisting that “free institutions, while they are essential to the prosperity and happiness of the people, always furnish the strongest inducements to peace and order."

A Democrat, he was defeated narrowly in the presidential campaign of 1880 by another Civil War veteran, Republican James Garfield. After Hancock died in 1886, President Rutherford Hayes said of him that, “when we make up our estimate of a public man…we can truthfully say of Hancock that he was through and through pure gold.”

Thomas Dewey

Thomas Dewey was one of the most respected men in America when he first ran for president against Franklin Roosevelt in 1944. Dewey came close to defeating Roosevelt that year—a remarkable achievement, given Roosevelt’s Olympian stature and the fact that the country was in the middle of a war (never a good time for a candidate looking to unseat a sitting president). Dewey had built a national reputation as a prosecuting attorney pursuing organized crime. He was so effective that one of the most powerful gangsters in America, “Dutch” Schultz, marked Dewey as a target for assassination. (Fortunately, Schultz’s criminal associates grasped the dangers of harming such a prominent public figure and chose to eliminate Schultz instead.)

Dewey served as governor of New York for 11 years, where he made a lasting impact on the state through the development of the New York State Thruway (which bears his name) and SUNY, the state university of New York. Under Dewey, New York passed the first state law banning racial discrimination in employment. Few governors made such a lasting, positive impact on the states they led.

After Dewey lost the 1948 presidential contest to Harry Truman in a surprise upset, Dewey went from being one of the most highly regarded figures in American politics to being remembered as the fellow caricatured by Alice Roosevelt Longworth as resembling "the little man on the wedding cake." Gone was the appreciation of what Dewey had brought to public life: his prosecutions of major crime figures, his highly successful work as New York governor, and the leadership role he played in steering the Republican Party away from its isolationism to its embrace of America’s premier role on the world stage.

Dewey was not a charismatic man, but he was a supremely capable and devoted public servant. The writer John Gunther observed that Dewey's appeal was derived from “the great American love of results."

Barry Goldwater

It was Barry Goldwater’s great misfortune to be the standard bearer for conservatism at a time when liberalism was on the ascent. The post-World War II affluence of the United States had enlarged the resources and capacities of the federal government. Goldwater understood that the temptation to use this great power for positive social change (such as the expansion of civil rights or the elimination of poverty) could result in the federal government having increased power over the lives of each citizen.

Goldwater’s fears were largely ignored in the heady, idealistic days of the early 1960s. It would take the turmoil of the late Sixties and the exhaustion of the Democratic party in the 1970s before the electorate embraced his point of view by choosing Ronald Reagan in 1980. Goldwater’s efforts helped reshape the Republican Party, moving it away from being, in the words of his Senatorial successor John McCain, “an Eastern elitist organization” to one that better reflected a national temperament.

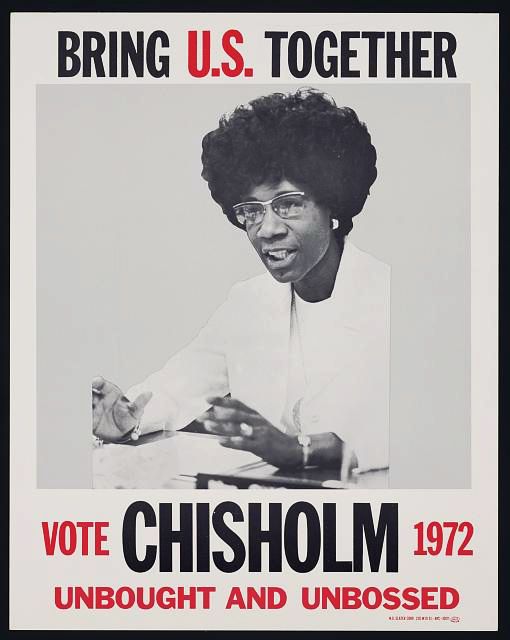

Shirley Chisholm & Jesse Jackson

When Representative Shirley Chisholm (in 1972) and Jesse Jackson (in 1984 and 1988) threw their hats into the ring, they were doing more than vying for an important job. They were sending a message that power in America was no longer going to an exclusive club for white men. They both knew that the odds were stacked against them, but that did not deter them. They changed the nature of presidential elections simply by participating.

Shirley Chisholm had a particularly daunting challenge. Apart from being an African-American running for the presidency just a few years after having her full status as a citizen recognized by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Chisholm had to contend with what we today call the burden of intersectionality--the way in which various prejudices (racism and sexism) combined can create a uniquely difficult set of obstacles. Chisholm related what she once heard from an older African-American man when she was seeking support early in her political career: "Young woman, what are you doing out here in this cold? Did you get your husband's breakfast this morning? Did you straighten up your house? What are you doing running for office? This is something for men."

In spite of this, Chisholm managed to build a successful career, first as New York state legislator, then as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1968. When she ran for president in 1972, she declared, "I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women's movement of this country, although I am a woman and equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people and my presence before you symbolizes a new era in American political history."

When Jesse Jackson campaigned in 1980, he did so not only as an African-American man and a civil rights veteran, but also as a representative of the liberal idealism that had dominated American life only a decade and a half earlier. However, like Barry Goldwater, Jackson the presidential candidate found himself out of step with the prevailing political winds in America. Nevertheless, he made a strong-enough effort in 1984 to try again in 1988.

The combined efforts of Chisholm and Jackson helped make possible the later candidacies of Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, and, by extension, all Americans.

American presidential contenders who don't win still merit consideration and recognition. In this time of major cultural change and conflict, when Americans are debating the purpose and meaning of public monuments and even whether or not the current president was legitimately elected, it is worth considering whether we should do more to honor the memory of those public-minded citizens brave enough to accept the challenge articulated by Theodore Roosevelt and to step into the arena.