At a moment when wealth inequality and industrial giants seemed irreversible, McClure’s Standard Oil story assigned a face to a phenomenon that many saw as outright evil.

Editor's Note: Adapted from Citizen Reporters: S. S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine that Rewrote America by Stephanie Gorton (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2020)

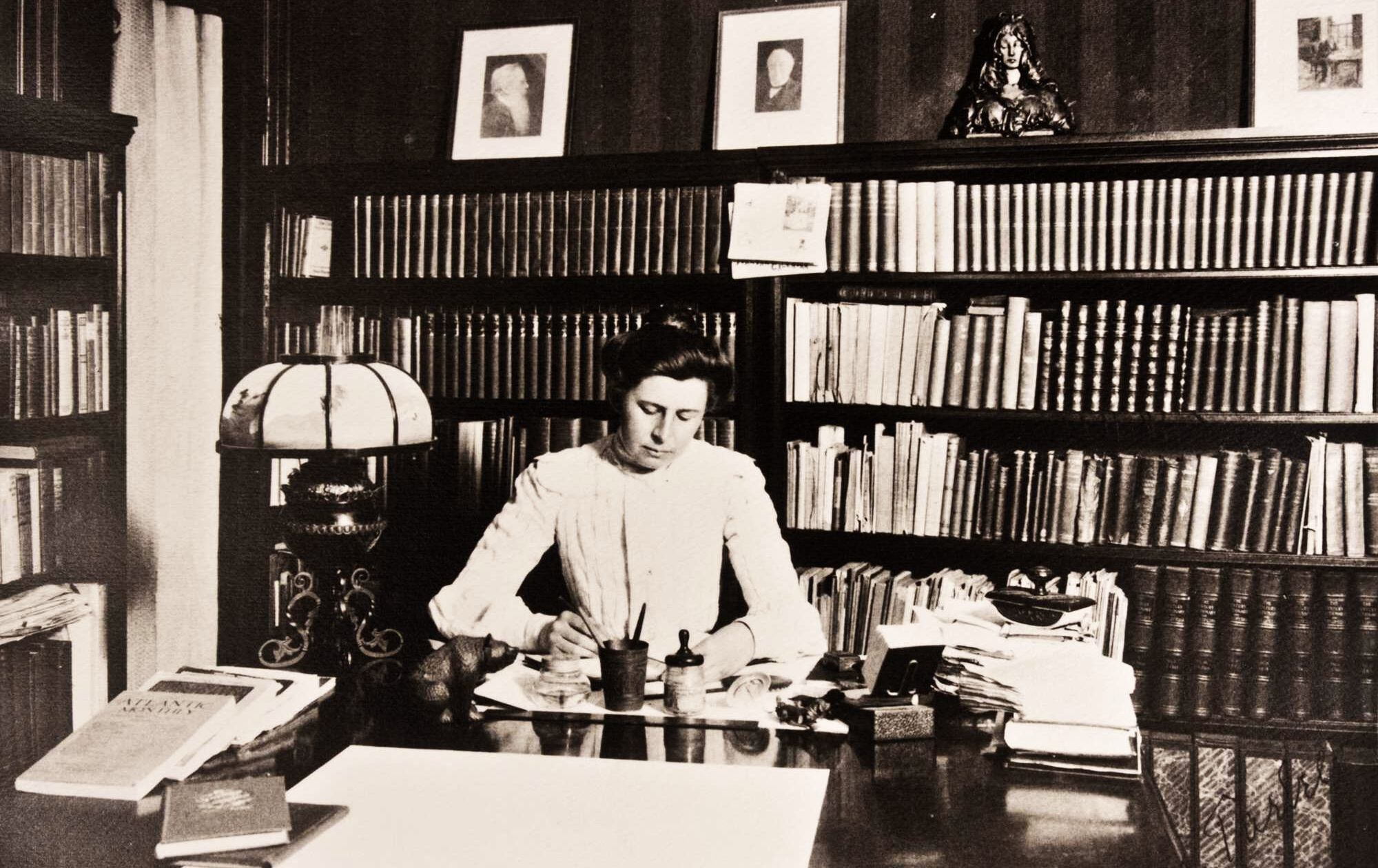

In January 1903, McClure's journalist Ida Tarbell was in the midst of an investigative series on John D. Rockefeller, and despite her stamina wearing thin, she forged ahead to construct one of the most comprehensive profiles of one of America's more controversial entrepreneurs.

It would seem as though, however, despite her fatigue, Standard Oil was not content with monopolizing the fuel industry, but it was determined swallow her life.

“It has become a great bugbear to me,” she told her assistant, John Siddall, adding that she longed to trade in the task at hand for a trip to Europe. Instead, her work plunged her into reliving one of the most fearful chapters of her youth: the brief rebellion against Standard Oil instigated by independent oilmen of Pennsylvania, like Tarbell’s own father, and memorialized as the Oil War of 1872.

It is a passionate piece of writing, balanced tightly between investigation and the vivid force of memory. The New York Times said the series was “[a]s readable as any ‘story’ with rather more romance than the usual business novel,” while the Boston Globe called it a work “of unequalled importance as a ‘document’ of the day.” The review concluded, “The results are likely to be far-reaching; she is writing unfinished history.”

Her editor, S. S. McClure, crowed victory. “You cannot imagine how we all love & reverence you. You are the real queen of the establishment,” he wrote from his own holiday in a French spa town. He wrote to Richard Watson Gilder, editor of rival magazine The Century, that the investigative turn of McClure’s reflected a new social responsibility that now belonged to the magazines.

McClure’s hope, he told Gilder, was to “get the people to see that we have been left simply the husks of liberty while the real substance has been stolen from us.” Magazines, he posited, had a better chance of waking up their readership than any other medium. “It evidently is up to the magazines to arouse this public opinion, for the newspapers have forfeited their opinion by sensationalism and by selling their opinions to a party.”

Tarbell described the Oil War from the perspective of the Pennsylvania oilmen; it was in this installment of the series that she pointed at her villain in no uncertain terms: “It was inevitable that under the pressure of their indignation and resentment some person or persons should be fixed upon as responsible, and should be hated accordingly. . . . It was the Standard Oil Company of Cleveland, so the Oil Regions decided, which was at the bottom of the business, and the ‘Mephistopheles of the Cleveland Company,’ as they put it, was John D. Rockefeller.”

The tinge of biblical language in her lines wasn’t accidental. At a moment when inequality of wealth and the rise of a few industrial giants seemed irreversible, McClure’s Standard Oil story assigned a face to a phenomenon that many saw as outright evil. Christian metaphor pervaded Progressive Era reform writing, and in time, McClure’s investigations were painted in newspaper cartoons and the popular imagination as spearheading a cleansing crusade against the mendacious rule of robber barons.

Despite high praise in the papers and McClure holding her up as an avenging angel of liberty, one of the final pieces in the series was giving her trouble. She was determined to write a character profile of Rockefeller himself — believing the epigraph she had taken from Emerson’s essay “Self- Reliance,” “An Institution is the lengthened shadow of one man” — but had no access to him. Her subject had been completely walled off from her ever since her rupture with Rogers.

She had no way to construct Rockefeller’s character from direct experience, so instead she worked from documentary sources and interviews, just as when she wrote her groundbreaking biography of Abraham Lincoln. Initially she let his publicly documented actions speak for his character. Then, as she gleaned more from records and witnesses, she began to get personal.

This yielded surprising sympathies. John’s estranged brother, Frank Rockefeller, tried to influence her portrait, offering “the most unhappy and the most unnatural” of the grievances she’d heard levied against the tycoon. Tarbell went to Frank’s office in Cleveland, entering the building in disguise so word could not leak out. She found him “excited and vindictive,” listened to him, and came away with a sad impression of Frank’s free spending and love of good horses, and John’s consequent disapproval and withdrawal of Standard stock from his brother during the Panic of 1893.

Tarbell found herself appreciating John’s hard wisdom and strict morals, rather than Franklin Rockefeller’s sense of entitlement, which she would try to convey in her profile. Her colleagues, though, insisted that grudge-driven anecdotes weren’t enough. She had to find a way to portray Rockefeller, the man, for the readers.

It took nearly a year to find the right time and place to see him with her own eyes. The mission tested Siddall’s sleuthing abilities. He finally laid a plan after a sympathetic reader divulged the tycoon’s churchgoing schedule. During summers at his Forest Hill home in Cleveland, Rockefeller rarely emerged in public — except for Sundays, when he would join the congregation at Euclid Avenue Baptist Church. Tarbell’s series had turned this weekly outing into an ordeal; crowds would gather outside the church to catch a glimpse of him, and Rockefeller had to be sure that Pinkerton detectives were on hand for security. It became his habit to greet a church attendant before the service with the query “Are there any of our friends, the reporters, here?”

On Sunday, October 11, 1903, they were indeed. After considerable reconnaissance by Siddall, three newcomers slid into the pews. Tarbell, Siddall, and illustrator George Varian sat, tense and perspiring, to hear Rockefeller speak at a Sunday school rally. Tarbell was agitated by the dark, stuffily decorated room, the covertness, and the physical presence of the man she had portrayed as a tyrant. The Sunday school room was “dismal . . . barbaric . . . so stupidly ugly.” Next to her, Siddall, she noted, was visibly triumphant, “nearly choking with glee. . . . I feared a scene on the spot.” Varian seated himself apart and tried to sketch the scene without attracting notice.

Rockefeller, Tarbell noted, repeatedly glanced at the gallery area where she was sitting, and she wondered whether he knew she was there. Feeling “a little mean,” she gathered her impressions of “the oldest man I had ever seen . . . but what power!” At the time, Rockefeller was sixty-four and she was forty-six. She saw a man with a large, clear yet deeply lined face, a thin nose “like a thorn,” and “no lips.” She noted his uneasiness, the darting of his eyes, and the sincerity of his voice. His fellow parishioners seemed to admire him, and Tarbell was surprised by the emotion that took hold of her as she took in the scene: “I was sorry for him. . . . Mr. Rockefeller, for all the conscious power written in face and voice and figure, was afraid, I told myself, afraid of his own kind.”

When it came time in the service to shake hands, she and Siddall went down to join the throng around Rockefeller. He looked Tarbell “fully in the face” before she quickly moved away. A blazing current of revulsion ran through her. “It was too awful,” she recorded just after the fact. In her loose handwritten notes from the morning, she wrote wildly of Rockefeller’s “colorless” eyes and, under them, “the puffiness I have long associated in men and women with sexual irregularity . . . Great power written on his mummy-like head and lust and death.” As if describing a Dickensian villain, she embedded her impression of Rockefeller’s morals into his physical features. His church, too, struck her as repugnant in atmosphere, filled with “stupid,” “stolid faces.”

She and Siddall did not linger, and Siddall tentatively suggested that they get drunk to relieve the stress of the morning. Instead Tarbell sought out some hotel stationery and began to write.

***

Writing about Rockefeller was an ordeal for reasons that ran deeper than the lines of his features. As a journalist, she was tasked with being a watchdog rather than an activist; the idea of a wholehearted character assassination made her pause. She knew she could not in good faith base her reportage on her feelings alone, but still that antipathy refused to subside.

Tarbell recognized her obligation to impartiality. She saw there was authentic industriousness, skill, and intelligence in the organization Rockefeller had assembled, and titled one of her chapters “The Legitimate Greatness of the Standard Oil Company.” She searched newspaper archives and set Siddall to searching for reports of Rockefeller’s professional deals, charitable gifts, and personal anecdotes; she asked Standard Oil competitors if they would be willing to share any letters or memos they had received from Rockefeller or his men. When it came to reporting on Standard Oil, “I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form,” she claimed.

Every word of this statement is worthy of interrogation, for she did have an animus against Rockefeller, a rancor that seemed to gather force as the series drew to a close. She knew there was little intellectual justification for hating a wealthy man for his wealth, even if much of the evidence she had painstakingly gathered bore out her suspicions of Rockefeller as an embodiment of a ruthless fortune hunter. Confirmation bias, or the application of newly discovered evidence to back up an existing frame of mind, undoubtedly figured into her skewering final profile of Rockefeller and his career. Her finished narrative sketched a bloodless tycoon, a parasite bent on bringing financial and moral disaster upon his host.

Even in the early installments of the series, her far-from-neutral feelings about Rockefeller were palpable. As one perceptive historian said of the character who emerged, “a reptilian John D. Rockefeller slither[ed] into view.” Her opinion became the hinge on which the narrative turned, gave it an activist quality, and extended it into a larger argument about society. As she argued, it was the perception and evidence that “they had never played fair” that turned Standard Oil from a company into a cause, a symbol of all that was wrong with big business’s scant regard for the individuals who fed it. “Human experience,” in Tarbell’s words, “long ago taught us that if we allowed a man or a group of men autocratic power . . . they used that power to oppose or defraud the public.” From her initial perception of the Standard as voracious and sly, her framing of the facts smoldered with judgment.

Much later, as she neared eighty, Tarbell told a friend that Standard Oil had cast a permanent sense of tragedy over her Oil Region home. She wrote, “This district saw and lived through the mad search for petroleum and the long labor to make it fit to give men more light, more power and heat. And along with it went the struggle of a few to get all that was in it for themselves. It was enough to curse the land forever.” Rockefeller was always, for her, the destroyer of home and hope.

The story of Standard Oil came to represent America’s moral fitness moving into the new century. “What I most feared,” Tarbell later wrote in her memoir, “was that we were raising our standard of living at the expense of our standard of character.” In the mythology of her own family’s struggles, the Standard’s scale had allowed it to suppress healthy individualism. In Titusville, she had seen what selling out to Rockefeller could do to a man’s place in society. “The most tragic effect I had seen in my girlhood,” she recalled, “was partial ostracism of the renegade . . . a man’s old associates crossed to the other side of the street rather than meet him.” As for herself, she wrote, “In those days I looked with more contempt on the man who had gone over to the Standard than on the one who had been in jail.”

McClure’s gave readers startling photographic portraits of Rockefeller to illustrate Tarbell’s narrative. One was taken after a bout of alopecia— for which, some said, her articles were at least partially to blame—had left him without any hair at all, not even brows or lashes. In another version he wore a black skullcap, provoking a wave of Rockefeller-as-Shylock caricatures. Through 1905, newspaper cartoons showed Rockefeller in a variety of wigs—some shaped like devil horns, others like octopus tentacles, still others like a forest of dollar signs. (A Detroit magazine, The Gateway, demonstrated the injustice of this editorial decision by hiring an artist to doctor a selection of portraits of great Americans—beginning, of course, with Lincoln—removing hair, eyebrows, and beard, to bizarre and uncanny effect.)

Rockefeller, an intensely private man, was no miserly hermit. He has been called “the greatest philanthropist in American history.” Rockefeller put his charity toward causes that Progressives might have applauded, had the source and size of his wealth not gotten in the way. The University of Chicago exists largely thanks to him, and he championed the cause of public health, funding schools at Johns Hopkins and Harvard. He funded a clinic for low-income women, and he also answered a plea from a school for black women in Georgia, becoming a major funder for what would later be Spelman College. Rockefeller himself was a devoted family man and churchgoer. He and his wife avoided high society in favor of playing with their children and landscaping their property, often rode the elevated train between home and the office, and built a public ice-skating rink next to the family home.

All this beneficence was turned against Rockefeller in McClure’s. Tarbell described his faith as “ignorant superstition.” Of his tightly budgeted household, she noted that “parsimony . . . [was] made a virtue.” She frankly disdained his home in aesthetic terms, putting bad taste on the same moral plane as monopolizing a natural resource. She called Forest Hill, the Rocke- feller manse outside Cleveland, “a monument of cheap ugliness.” About his legacy she wrote, “Our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner for the kind of influence he exercises.” She concluded that he was a calculating master of compartmentalization; there was a dual personality at work, she wrote, capable of corruption and bullying on a grand scale and clean, simple living in private.

As one of Tarbell’s own biographers has noted, her slant on Rockefeller is nearly as revealing of the author as the subject. Her tentative boundary between the professional and personal spheres of life was being dismantled. More and more, it seemed her heart itself hung in the balance.

***

After Cleveland, Tarbell returned to New York subdued by her sneaky encounter with Rockefeller, yet driven to finish what she had started. Emotion began to drain from her, and she had some trepidation about her character study being read by an attentive critical audience, as she wrote Siddall in early December 1903: “I think I shall watch the effect this article produces on the press more anxiously than any other. . . . I feel sometimes that my judgment of these papers is all raveled out; by the time I get to the end of one I cease to have any feeling about it at all.”

She underestimated her own ability to convince readers. The Chicago Inter-Ocean called her series “one of the most stirring in our commercial history,” an endeavor that “illustrates most strikingly the strange new conditions of business life in America.” Perhaps most complimentary to her scientist’s heart, the New York World said her work “gives us the same insight into the nature of trusts in general that the medical student gains of cancers from a scientific description of a typical case.” “Woman Does Marvelous Work” exclaimed another paper, while the New York Globe called the series “so thrilling and dramatic that even those superior people whose boast is that they never read a serial made an exception for this one.” One day a determined man appeared in the McClure’s office and asked Tarbell to get her hat: he intended to marry her and take her out west.

Tarbell kept a scrapbook of all her reviews, including one announcement that S. S. McClure had been rejected from Westchester County’s Ardsley Country Club by Standard supporters. One club member wrote to the Chicago Examiner to explain the decision, signing himself “A Gentleman”: McClure, he wrote, “has forfeited his right to associate with millionaires, with gentlemen. He is the publisher of a magazine, and to that magazine he has admitted a history of the Standard Oil Company which is to the last degree offensive, not only to the Rockefeller family, but to all safe, sane and conservative citizens. I do not assert that the history is untrue; my point is that it discloses to the public in the most daring and reckless way the methods by which giant fortunes are accumulated.” He concluded, with foot-in-mouth earnestness, “it is high time for the higher orders to assert themselves.”

Despite Rockefeller’s work as a philanthropist, his money was now seen as contaminated. Increasingly, politicians and institutions turned away gifts from the nation’s richest man, whose net worth was around 1.5 percent of the country’s total economic output—roughly equivalent to triple the wealth held by Bill Gates in 2019. Starting in 1904, Theodore Roosevelt declined campaign donations from Standard Oil, keenly aware that public image, once compromised, rarely recovers. A newspaper cartoon showed the harried, top-hatted tycoon asking a newsstand merchant, “Have you any reading matter that isn’t about me?” Mark Twain wrote a satirical “Letter from Satan” to Harper’s Weekly, protesting the new vogue of rejecting Rockefeller’s contributions: “In all the ages,” he wrote, “three-fourths of the support of the great charities has been conscience-money, as my books will show.”

After Tarbell’s write-up from the church, arguments and counter-arguments about Rockefeller’s ethics, and hers, ricocheted through the media, from the Newark News to the Sacramento Bee and abroad, to Canada, Germany, and France. The Nation printed a scornful review, which cut Tarbell deeply. The Denver Republican predicted that Tarbell’s reputation would endure as “the greatest of all literary vivisectionists.” One of the most partisan attacks came from a small newspaper, the Derrick, of Oil City, Pennsylvania, under the headline “Hysterical Woman Versus Historical Fact.” The Derrick was faithful to the Standard, accusing Tarbell of being “venomous,” producing “history made to order,” and single-handedly discrediting the literature of exposure.

Gender was a frequent theme among critical letters and reviews. In the near-universal acclaim for her Lincoln series, the fact that she was a woman was rarely mentioned as a factor behind any guiding quality of the work. The Rockefeller profile provoked a very different reaction, one that derided a “nagging,” “scolding” Tarbell for seeing her subject through the blurry lens of unchecked subjectivity. In the words of one Detroit-based critic, “it should not be forgotten that Miss Tarbell, as her name implies, is a woman . . . [w]ith all a woman’s weakness of will, ideals of manly beauty, desire for showy entertainment, magnificent dinners, [and] personal adornment.” In sketching a monster, the writer argued, Tarbell had shown herself as being monstrous. She was, like all women, “ruled by her sympathies.”

A diverging but equally reductive tack painted Tarbell as robotic and merciless—unnatural qualities for a woman. One Los Angeles reporter, comparing her to her colleague William Allen White, wrote that while White was bubbling and exuberant, “Miss Tarbell’s wonderful intellect is a pitiles [sic], disinterested, white light. ” She would long be seen as a fascinating enigma; twenty years later, as she toured the Midwest on the speaking circuit and sat by the stage as local luminaries introduced her, she would hear herself described as a “notorious woman” and the subject of long musings as to why she had never married.

There were entire books published in protest of Tarbell’s investigation, too. The best-known rebuttal started as a Harvard senior thesis. Gilbert Holland Montague, with the collaboration of Standard Oil’s in-house lawyer, hastily finished The Rise and Progress of the Standard Oil Company in 1903. Montague’s book was, in Tarbell’s view, “not exactly a best seller but certainly a best circulator” — and deliberately so. Public libraries were sent generous stock by an anonymous funder, and ministers, teachers, and politicians similarly received free copies from the publisher. She read Montague’s account as soon as she could, noting that it “separated business and ethics in a way that must have been a comfort at 26 Broadway.”

When Rockefeller was questioned about Tarbell’s series, he was tight-lipped, saying only that her claims were “without foundation” and that “it has always been the policy of Standard Oil to keep silent under attack and let our acts speak for themselves.” The idea of directly contradicting McClure’s struck him as “unstatesmanlike.”

When allies of the Standard urged him to respond, he answered, “Gentlemen, we must not be entangled in controversies. If she is right we will not gain anything by answering, and if she is wrong time will vindicate us.” He had decided to play the long game, but could not have known how long it would remain in the forefront of public consciousness. Tarbell had not yet finished her series, which would be compiled and released as a book two years later and bolster a Supreme Court case against him soon thereafter.

Rockefeller even once claimed not to have read McClure’s, but his wife’s amanuensis accidentally broke his cover when remembering a long trip she took with the family in the spring of 1903. “He liked to have things read to him, and during these months I read aloud Ida Tarbell’s diatribes,” she recalled. “He listened musingly, with keen interest and no resentment.” When prodded, he said that Tarbell made “a pretense of fairness” but “like some women, she distorts facts, states as facts what she must know is untrue, and utterly disregards reason.”

Rockefeller refused to budge from his decision to remain silent. One day, walking near his Forest Hill estate, a friend questioned this policy. Rockefeller told him, gesturing toward a worm in their path, “If I step on that worm I will call attention to it. If I ignore it, it will disappear.” But to those in his circle, he showed a flinching resentment against Ida Tarbell and her story. Her perspective seemed to fit in with his sense that the world turned against true greatness and leadership.

“Not a word about that misguided woman,” he said when he heard her name. To one acquaintance, he remarked, “Things have changed since you and I were boys. The world is full of socialists and anarchists. Whenever a man succeeds remarkably in any particular line of business, they jump on him and cry him down.” The concerted PR campaign to counteract Tarbell’s influence was quietly sustained for years.

Outside of direct rebuttals, derivative stories for all kinds of audiences sprouted up. One was a play inspired by Tarbell’s series. In The Lion and the Mouse, heroine Shirley Rossmore determines to expose the man who betrayed her father; she claims to be a biographer to gain access to John S. Ryder, the world’s richest man. But he falls in love with her, and makes an offer she cannot refuse. Tarbell herself was offered the starring role for a fee of $2,500 per week for twenty weeks, the highest offer yet made to an American theater actress; unsurprisingly, she declined.

Tarbell yearned to return to writing about history long past: writing about the dead seemed much easier than trying to deliver a fair and accurate picture of the living.. “There would be none of these harrowing human beings confronting me, tearing me between contempt and pity, admiration and anger, baffling me.” Her brain was “fogged,” hastening her desire to put the story behind her and start something new.

Instead, she would become mired in a new calamity — one that would lead to the dissolution of McClure’s at the very height of its power and prestige.