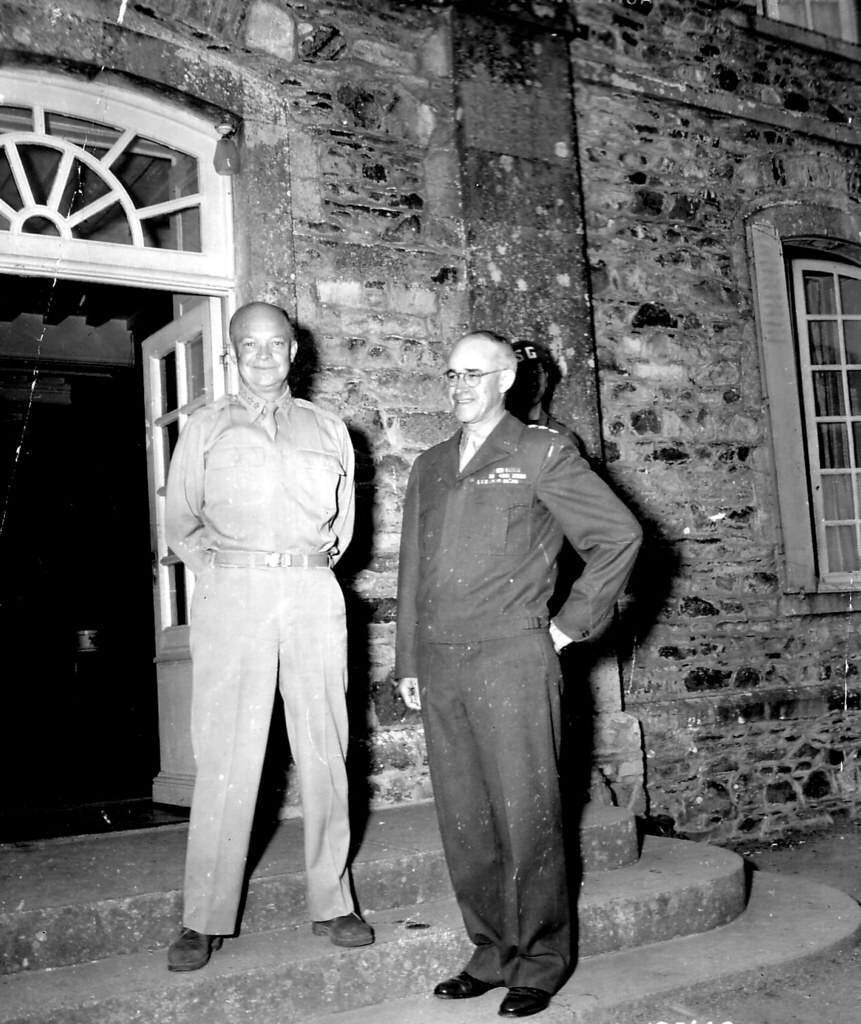

The former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and classmate of Eisenhower's recalls his years with Ike.

Editor's Note: In a conversation with the editors of American Heritage recapitulated here, General Omar N. Bradley spoke about the years of his closest association with Eisenhower, from 1943 through 1945. Following his service in World War II, General Bradley served as Army Chief of Staff and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

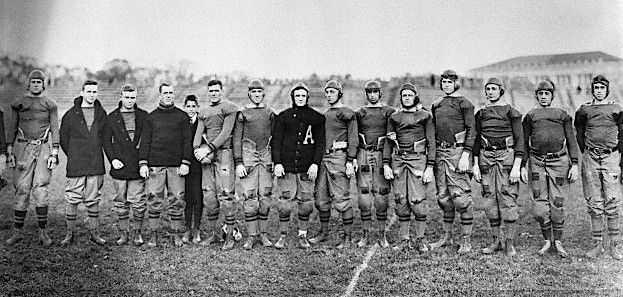

Ike and I were in the same cadet company at West Point, so I saw him several times a day at formations. He was very well liked by everyone and was very active in class affairs. He was on the football team until he hurt his knee, and after that he was a cheerleader. He was also on the staff of the yearbook put out by the graduating class. We had a lot of good men in our class, but I don't think we looked ahead to wonder if Ike or any other one would attain high rank. You see, promotions came slowly at that time. In fact, some of the infantry officers were second lieutenants for as long as six years. If you were young for your class (as Ike was not, but I was), you thought you'd be lucky to become a colonel by the time you were sixty-four.

I didn't actually serve with Ike until 1943. I arrived in North Africa on February 24, just two or three days after the action at the Kasserine Pass started. I was at Eisenhower's headquarters in Algiers until the twenty-eighth, and then I went up to the front. You see, I was sent over there as sort of a personal observer, or representative, of General Eisenhower: he told me that he was not going to prescribe where I went, but he wanted me to take a look at things I felt he would want to see if he had the time. Following that directive, I went up to the front to talk with some of the men who had been in the Kasserine fight. I wanted to find out how effective our equipment was and how effective our training was.

We were working on a shoestring in North Africa, defending part of a wide front thinly. In such a situation you're apt to get smashed somewhere, and that's what happened at the Kasserine Pass. But Ike wasn't discouraged. He came to the front frequently, at least once every week or ten days. He never gave direct orders to the men in the field, of course, but he liked to talk with them. I've seen him sit in the shade, leaning up against a tree, and sign autographs for three-quarters of an hour. I remember one time in France, while his headquarters were still in London, he flew over to talk to me, and when we took him back to his plane, we got to talking to a bunch of enlisted men, and he started signing autographs. After half an hour, I finally stepped in and said, "Look, you'd better be getting back before dark." He certainly enjoyed talking to the men about where they were from and where they had gone to school and things like that whenever he had the chance.

I sometimes thought that if I had been in Ike's place, I could not have put up with some of the things he had to put up with, and I've heard him say since that maybe he wouldn't have put up with some things if he had it to do over. But he got results. His ability to compromise enabled him to get the maximum out of the British—Montgomery, for example. He had to argue with Montgomery quite a bit. But when Ike finally got firm about something, Montgomery would always say "Yes" and go along with it.

Eisenhower went back to England sometime in January, 1944. Before that, the plans for D-Day were more or less tentative. We had to wait for a decision from the commander —whoever he was to be. We assumed it would be an American, either General Marshall or General Eisenhower. The President finally decided that General Marshall could not be spared from Washington, so Eisenhower was designated.

All the intelligence pertaining to enemy units, the terrain, and so forth had been collected by the staff before Ike came. But after studying the information and the plans, he decided that it looked like too much of a shoestring operation, and he immediately started to broaden it. He increased the invasion force and asked General Marshall and the American Chiefs of Staff to strengthen the effort by bringing in part of the Navy from the Pacific.

I felt that it was imperative to drop airborne forces back of Utah Beach, but the plan was opposed by the British air officer in charge of the airborne operation; he felt that such a maneuver at that critical spot would be suicidal. General Eisenhower agreed with me that the whole invasion would be jeopardized if we eliminated the drop. As it turned out, the casualties at Utah, including the airborne people, were no higher, percentage-wise, than those at Omaha Beach. We did have casualties, yes, but the mission was accomplished.

Of course the most difficult decision Ike had to make was to go when we did on D-Day. At the time I was skeptical, I must admit, because the weather was so bad. Yet it turned out to be a blessing because the German air forces could not pick us up coming across. The waves were so high, however, that I was afraid we would have trouble getting ashore. We did lose our floating tanks, on which we'd counted a great deal, because the waves were too high for them. But that was more than offset by the fact that we were able to attain considerable surprise. As a matter of fact, if we had waited two weeks, which was the alternative to going when we did, we would have run into a big storm that would have made a landing impossible. We would have had to put it off for four weeks, and by that time our security might have been jeopardized because too many people knew about it.

Another crucial decision was whether or not we were going to let Montgomery make one single thrust north of the Ruhr toward Berlin. Ike was under terrific pressure from the British to let Monty go it alone, and he took a long time to make that decision. I think he felt Montgomery was wrong from the first, but he needed some backing on it, and he finally got it from the American Chiefs of Staff. So we advanced on a broad front. I personally think it would have been a great mistake to let Monty have his way. Suppose they had hit him in the flank with the twenty-six divisions they hit us with in the Ruhr? They'd have ruined him.

What made Eisenhower the right man for the job in Europe? Well, his ability to get along with the Allies and to make an allied force work was of great importance, and so was his broad knowledge of tactics and strategy. And of course there was his ability to make decisions. Even as a junior officer, he never hesitated to make decisions. When he was in charge of the Plans and Operations Division of the General Staff in Washington under General Marshall, he once ordered a whole division overseas without ever talking to Marshall about it. He felt that General Marshall had given him the job of putting troops in to fit requirements, so there was no need to check with the General before ordering the division abroad.

That was in accordance with Ike's general theory: you give a man a job and leave him to do it. That's the way he operated with us; he told us what he wanted done instead of telling us how to do it.

Ike was very good at sizing up his subordinates, too. We always talked personnel when we got together. I would keep him informed of how various commanders were doing. There might be some outstanding colonel who I thought ought to be made a brigadier general later; if so, I would always clear it with him so that he'd know all about it before I sent the recommendation to him officially. And he would also call to my attention someone he thought was doing well.

He had two other qualifications you must consider, great mental and physical energy. He got around a great deal and was on the job all the time. I remember a conversation we had during the war. We said we were probably living three years of our lives in one year of combat. He was a soldier of many talents — and a man of many lives.