The second-oldest of Ike's brothers compares and contrasts each man's achievements while recalling their childhoods in Kansas.

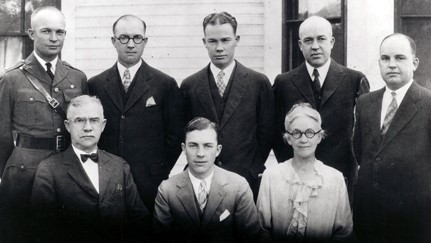

Editor's Note: The following account is from a conversation the editors of American Heritage had with Edgar Eisenhower in 1969. Eisenhower, aka "Big Ike," was a lawyer and businessman and the second-oldest of the Eisenhower brothers.

It was not until [Dwight] was elected to the Presidency that the entire family was pulled into the limelight. The full realization that life never again would be quite the same for us was driven home to me as I stood with the family watching Dwight take the oath of office at the inauguration ceremonies in 1953. The pageantry and solemnity of the occasion would be impressive to any American, but it certainly touched us deeper. There was our brother, Dwight David Eisenhower, taking the same oath that George Washington and Abraham Lincoln had intoned. He was standing there, a figure that would be secure in the history books for all time. Generations of school children would be reading about Dwight Eisenhower two hundred years from now. It was an eerie and solemn feeling.

I doubt if ever I shall be so deeply stirred again. The Presidency had become something near and personal. I was remembering Dwight at that moment only as my kid brother, the tyke I had once shared a bed with, back in Abilene; the scrappy little guy I had battled all through boyhood. . . .

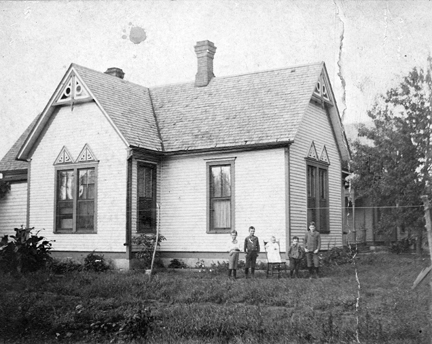

Our lives as youngsters were full and purposeful. There was plenty of fun and good old-fashioned pranks. We played games that kept us happy and exuberant. But behind all of this activity was a stern daily routine of constant discipline and the solid exposure to the principles of life and the values that were planted and developed in our minds.

Mother, I am sure, was proud of her sons. There were times, of course, when we were noisy and a little too enthusiastically original, but still we were healthy and faithful and good natured. Each of us had individual complexities, needing pulling or pushing occasionally, but Mother always seemed to know what to say and what to do to straighten us out. . . .

To help meet household expenses, Mother often sent Dwight and me over to the north side of town with our little red wagon loaded with sweet corn, peas, beans, tomatoes, and eggs. We concentrated on those who never had gardens of their own. Knocking on all those doors distressed me. I didn't like the attitude of the customers, nor the way they fingered our vegetables, taking only the nice ones and paying us only a slim price. Some of them even made nasty remarks about our produce, even though I knew our stuff was as good as could be found in town. I resented this. It admittedly made me feel a bit inferior.

I suppose this is the reason I always felt that the railroad tracks separated Abilene into two classes—those who lived north of the tracks were, in my mind, a little bit better than those who lived south of the tracks. Being a little older than Dwight, I was perhaps more sensitive than he was about this, because I mentioned my feeling to him many years later and he said he never had any such feeling. I never outgrew it, however. I have since realized that you must take a lot of abuse in life while you are working your way up, but I also feel anyone who is making an honest effort to better himself is entitled to some respect. . . .

There are just so many hours to a waking day, even if every minute of them is occupied attending school, working at odd jobs, or playing on some athletic team. But all of us found time to participate in the cross-town encounters.

This wrangling persisted only after we transferred to the intermediate school over on the north side of town. You see, there were only six grades at the south side school where we first attended, so we had to go to the north side for the seventh and eighth grades and for high school. The north side kids resented our coming to their school. So there were fights. We didn't go around looking for them, but we never ran from fights either.

These fist-fights between the best fighters from the north and south sides of Abilene were never actually planned affairs. No one knew in advance who the combatants would be. They just happened. Something would boil up in a game, or while marching into school, and the next thing we knew a battle was on. If it was a real good scrap, that settled everything between north and south, and we were accepted.

On one occasion I got involved in one of those scuffles, and another time Dwight battled for our honor. Both fights were real grim battles. Dwight's scrap happened about a year after mine.

He was about fifteen years old and smaller and more slender than he was when he went out for football at West Point. His match paralleled mine in some respects. His opponent was much bigger, and older, too; a heavy-set, thick-necked boy named Wes Merrifield. Dwight seemed to be over-matched. To look at them together on the street you would have thought that Wes would have killed him. But my brother could take a punch, and he could deliver one. He wasn't too fast, but he had our dad's fighting heart and stubbornness, and he refused to go down easily. . . .

It was toe to toe slugging for nearly two hours, neither boy admitting defeat or giving quarter. Finally when their strength was gone, both boys realized it was useless to go on. . . .

A lot of the kids who hadn't given Dwight much of a chance rushed up to him and slapped him on the back. To them, he was a hero, but he didn't feel like one. To me, the fight showed Dwight's dogged determination and tenacity. These are traits that have stuck with him through the years and have helped him over many a hurdle when things looked black. . . .

During our senior year in high school Dwight and I had talked about going to college. We knew we were too poor for our parents to help both of us at the same time. So we decided that I, being the older, would first go to college one year. Dwight would work and give me his earnings and then I would stay out of school the next year, work, and give my earnings to Dwight. We planned to alternate in school this way until both of us were graduated. It would take eight years to finish the four-year course, but we were willing.

So off to Michigan I went. In my first year I enrolled in the Literary School. Dwight, true to his word, got a job and sent me $200 of his salary. Now that I think about it, I never did pay him back the loan, and he never asked for it. But it set a pattern for the family. We have always helped each other from that time on. I have paid more than the $200 to other members of the family. . . .

Incidentally, Dwight stopped off at Ann Arbor to visit with me on his way to the Point. This was to be the last time for fifteen years that we were able to get together. The next time I saw him was in 1926 when our family held a reunion at Abilene.

Our oldest brother, Arthur, was the first of the Eisenhower sons to achieve material success. While Dwight was at West Point and I was at Michigan, Arthur set a pattern for the rest of us to follow by getting a job as a messenger in a Kansas City bank and working his way up. He was just getting established in banking while Dwight and I were in school. To help meet living expenses, Arthur got himself a roommate. . . . It was Harry S. Truman! . . .

Though we have always had a lot of affection for one another, people have asked me, "Ed, hasn't there ever been any envy or jealousy among you brothers?"

"Heck, no," I reply, honestly. "As a matter of fact, we are probably mentally boosting one another all the time."

Personally, it has never occurred to me to be the slightest bit envious about any of the successes of my brothers. I know they feel the same way. Why on earth should anybody be jealous of a member of his own family? I think a person should be proud of anything one of his brothers contributes toward the good of mankind. Dwight, of course, has done far more than any of the rest of us for his country, but we have all tried to be contributing Americans.