The former President of Johns Hopkins University and youngest Eisenhower brother remembers life in Kansas at the turn of the century.

Editor's Note: The following account is from a conversation the editors of American Heritage had with Milton S. Eisenhower in 1969. Dr. Eisenhower was a lawyer and educator and the youngest of the three Eisenhower brothers.

It was a quiet, law-abiding place. Everyone was putting something in: the town was putting in paved streets, Dad was wiring our house, I was able to equip our home with a serviceable gas water-heater. When the first automobile came rolling into town (a White steamer, as I recall), everyone stopped to look and make comments on its impracticality.

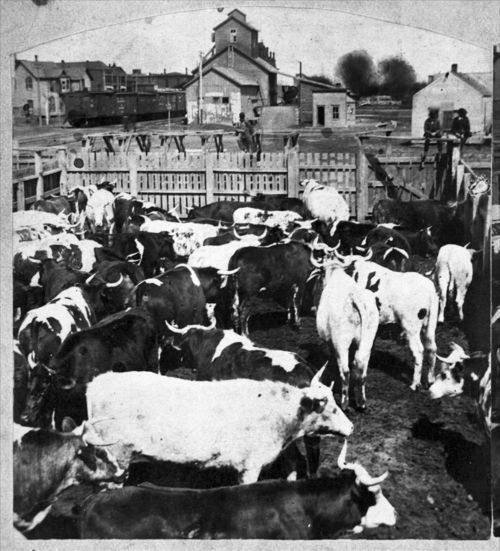

There was little evidence of Abilene's former frontier character — cattle driving, drinking, and shooting — though all of these were a part of the local stories we delighted to hear. The stories had long since lost whatever accuracy they may have once possessed. Remember that my grandfather brought his family from Pennsylvania in 1878, and my mother came from Virginia to join a brother at Topeka at about the same time.

We boys were two full generations removed from the frontier dramatized in modern Westerns. The earliest excitement I personally recollect was the flood of 1903. There was, nevertheless, a residuum of the pioneer spirit in the town's unsophisticated atmosphere, its ingrained friendliness, and its isolation from the rest of the world.

The isolation was political and economic as well as just a prevailing state of mind. Politically, I can't remember anything earth shaking happening at all, anything that threatened the firm control that the Republican party had exercised on the region ever since Kansas' stormy Civil War days.

People still talked about the visit William McKinley made to Abilene before I was born: the three elder Eisenhower brothers led the parade, carrying torches. Economically, of course, the town had advanced far beyond those early days when, as Dad expressed it, the main problem was "how to trade eggs for sugar and salt." But, beyond the shipment of grain by rail out to the East, there was very little outside contact. Self-sufficiency, personal initiative, and responsibility were prized; radicalism was unheard of.

So it's little wonder we boys grew up to be moderates and conservatives — in short, Republicans.

Socially, things were a bit more complicated, or so my brother Edgar felt. He has contended that Abilene was split by tracks running east and west, and that although there were many crossings, some of them were too difficult to make. On the north side were the more affluent residential areas of the town; south of the tracks were lovely but more modest dwellings — and the Eisenhowers.

The elementary school we all went to was right across the street from our house, but the seventh and eighth grades were in a building on the north side, the Garfield School. Making that transition was a real challenge for several of my older brothers. Edgar and especially Ike each got involved in a whale of a fight when they made the change, fights that became as much a part of the Abilene story as anything that Wild Bill Hickok had done. But by the time Earl and I came along, all was serene and uneventful. Perhaps Ike had settled the issue for all time.

I honestly don't remember the rivalry with the north side boys that Edgar has spoken and written about. One reason for this may be that Edgar often had the job of taking the surplus vegetables we grew in our garden across the tracks in a wagon and selling them to the "snooty" families of his schoolmates.

My regular after-school job — working in the drug store — was free of any such hostility. And I don't think that Ike, who pulled ice at the creamery, ran into much of it there either. In addition to jobs like these, which we took in order to bring in extra cash for the family, there were numerous chores that had to be done. The garden had to be hoed, the orchard tended to, the cow barn cleaned, or the horses rubbed down.

Of all these regularly rotated chores, the least desirable by far was getting up at 5 A.M. to light the stoves. But there never seemed to be a lack of time for our big meals or for family fun: the rule was that after you had done your lessons, your chores, and your work, all your free time was your own.

Some of the free time, of course, was taken up with going to church, or with Bible readings. We all went to the River Brethren Sunday School, and Grandfather, who was a minister of the Brethren and who lived with us, never seemed to lose his ministerial aspect. His black beard and black tie were the trademarks of his calling. It is striking that in the earliest group picture of our family (1902), Father, a man of the new century, wears no beard — just a small mustache — and no tie.

Mother had been raised as a Lutheran, but at the time I can remember best she had become interested in the Bible students of the Watchtower Society. It was she who organized the meetings that used to fill our living room on Sundays. And it was she, with her consistently biblical approach to life (when she was a little girl back in Virginia, she won a prize for memorizing 1,675 verses of the Bible in six months), who saw to it that religion would be just as much a part of our home life as eating or sleeping.

Dad's devotion to the Bible may have been less doctrinaire, more intellectual, than Mother's: he kept a Greek edition by his bedside for checking questions of interpretation or punctuation. But his pacifism, though less outspoken than hers, was no less heartfelt.

That old religious abhorrence of war — who can say now that it was naive? — was in some ways a troublesome conviction. As World War I developed, everyone in town was down on pacifists and all things German. At one point, even though several of her sons were in uniform, Mother was in real danger of being arrested because of her articulate pacifism and her German-sounding name. It was only the intervention of an influential friend that kept her out of jail.

Ironically, in World War II, I was given the loathsome job of resettling the Japanese-Americans on the West Coast (there was then no anti-German sentiment whatsoever), but I found I had a terrific struggle with people who wanted to treat these citizens with the senseless severity that had been directed toward persons of German descent in 1917.

There must have been a real conflict in Mother's heart when Ike got his appointment to West Point. Neither she nor Dad took any part in helping him make that decision. And with the rest of us, their hands-off policy was the same, perhaps because Dad continued to feel strongly that Grandfather had made a mistake in trying so hard to get him to be a farmer.

The only exception that I recall to this policy was the openly expressed hope that Edgar might be a doctor (as it turned out, he wanted to become a lawyer, and did so). Ike, on the other hand, at that time was not sure of what he wanted to do. He had been in everything at school (on teams, in societies, etc.), and through it all he was a good student. I think he was confident that the right thing would turn up. And of course it did: when Swede Hazlett came home from Annapolis, his accounts of life and education at the academy made a big impression on Ike and succeeded in interesting him in Annapolis and West Point.

Knowing that he was a good student and had friends to back him up (particularly the editors of the town's two newspapers), Ike was reasonably confident of his chances. And what motivated him to try for Annapolis or West Point was doubtless the prospect of getting a good education free — that was surely as important as the idea of a military career. Ultimately I believe it was the age factor (at the last moment he learned he was too old to enter Annapolis) that made him decide to go to West Point.

The idyllic, withdrawn character of Abilene changed, of course, as World War I developed — just as the careers of the Eisenhower brothers branched out then from their home town. Without saying so we all apparently shared the belief that "If you stay home you will always be looked upon as a boy." I happened to be home when Ike left to get the train East in 1911; Mother seemed perfectly composed, but after he left she cried.

It wasn't because of her pacifism, however, that Mother seemed rather indifferent toward the success of Dwight as a professional soldier. She simply had her own standards, and they were different. She did not consider success to be related to rank or position or income; a great man was considerate and good — this was the sole criterion. Indeed, when asked after World War II whether she wasn't enormously proud of her famous son, she replied, "Which one?"

This was not a clever response; it was wholly harmonious with her philosophy. Another anecdote along these lines is that during the war a traveling lady from New York went out of her way (she was San Francisco bound) to go to Abilene and meet Mother. When Mother gathered that the lady had a son in uniform she exclaimed, "Why, you know, I have a son in the Army in Europe, too!"

In family reunions spread over the past two decades, we brothers have talked much of our early, gay, and satisfying life in Abilene. On one thing we are agreed: the total environment and certainly the simple rules in our home taught us as youngsters to be self-reliant, independent, and responsible. I have often felt, and I suppose I still do, that urbanization, with its congestion of living, its lack of truly responsible things for youngsters to do, is less conducive to stimulating the development of these qualities than is life in a community like Abilene.

Thomas Jefferson, in the late 1790's, argued that democracy was nurtured in, and wedded to, the rural areas. However, he lived long enough to see the beginnings of urbanization and specialization in working; so he then argued that we could keep democracy only so long as there was a rising level of education and understanding among all the people, for only then would the mass judgment by those who hold the basic social power possibly be valid.