During Pres. Washington’s first term, an epidemic killed one tenth of all the inhabitants of Philadelphia, then the capital of the young United States.

-

Spring 2020

Volume65Issue2

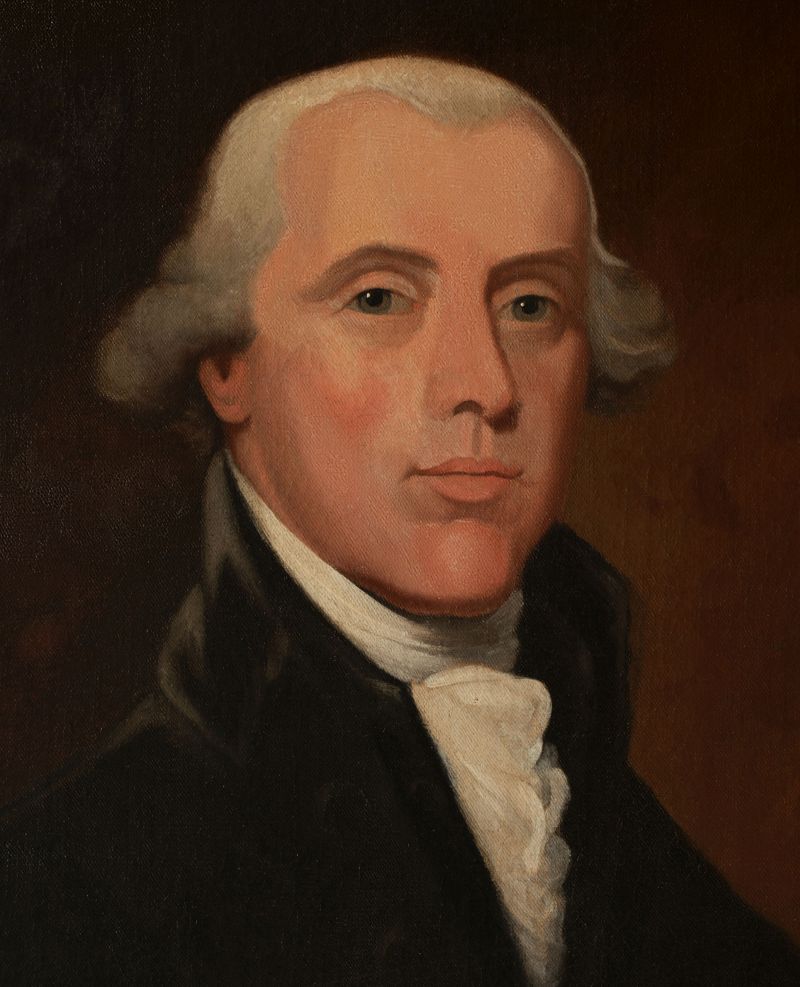

Editor’s Note: Stephen Fried is a journalist and bestselling historian. He adapted the following essay from his recent book on America's first famous physician, Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father (Broadway Books).

Near the end of almost every summer in Philadelphia, people suddenly began worrying about illness, wondering what a cough or an ache might mean. But in August 1793, with the President, his cabinet and Congress returning from summer recess, something more fearsome seemed to be happening.

“A malignant fever has broken out in Water Street,” wrote Benjamin Rush, the leading doctor in the city, to his wife Julia, who was off with their children in New Jersey. The illness had “already carried off twelve persons” on one block — one of whom died only twelve hours after the first symptom appeared. Rush had treated eleven patients so far; three had already died, while the others were barely holding on.

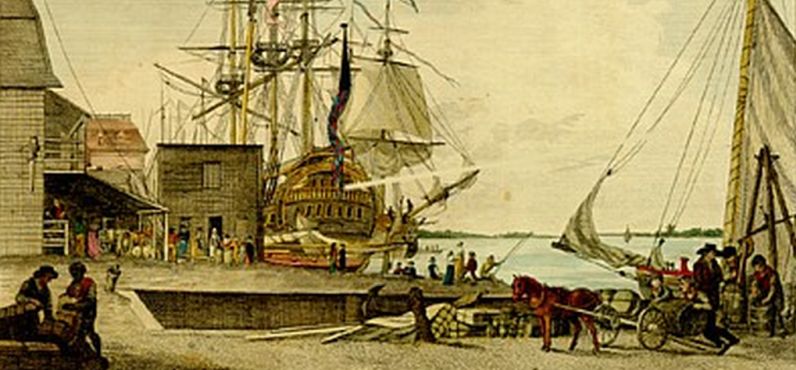

Rush prayed the fever wouldn’t spread “beyond the reach of the putrid exhalation which first produced it.” All the deaths were concentrated in one small area close to the river, north of Market Street, and doctors as well as port officials initially believed that the disease was caused by a toxic air “produced by some damaged coffee which had putrefied on one of the wharves.” At the moment on August 21, nobody was sick except those who lived within a summer breeze of the contaminated coffee.

But then the illness spread, block by block, toward his house. “The fever,” Rush wrote, “has assumed a most alarming appearance. It not only mocks in most instances the power of medicine, but it has spread through several parts of the city remote from the spot where it originated.” He remembered the 1762 yellow fever epidemic from his apprenticeship and had seen a few lesser outbreaks since. He knew the symptoms to watch for in patients, and the sad inevitability that when their eyes turned yellow and their vomit black, there was no hope.

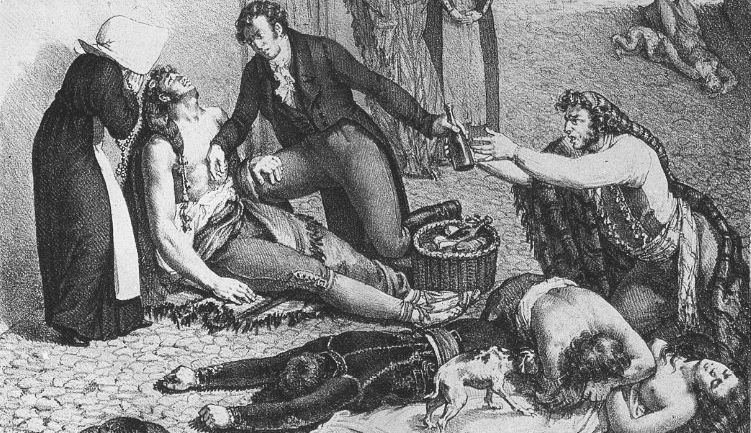

Just that morning Rush witnessed a scene that reminded him of histories he had read of the black plague: a young merchant and his only child died almost simultaneously, the wife frantic and inconsolable with grief. And he had lost nine other patients in different parts of the city.

By August 25, Rush was meeting with his fellow doctors at the College of Physicians — the nation’s first medical association — to discuss the growing epidemic. Many of them didn’t show up, because, as Rush told Julia,, they were already “flying from the city.” But those who attended had pored over their medical books, looking for answers and possible courses of action. While these doctors had histories of personal clashes, they were able to agree on what should be done to prevent and treat the illness. Rush was selected to write up the college’s prescriptions — the new nation’s first public health decree. One key piece of advice was “to put a stop to the tolling of the bells” for funerals — since so many people were dying.

The doctors recommended that people avoid “unnecessary intercourse” with anyone infected, and that a mark (a small red flag) be placed on the front of any house with an infected person inside. Patients were to be placed in the center of large and airy rooms, in beds without curtains, their linens frequently changed and washed and “all offensive matters” removed from near them.

In these days, all but the poor received health care at home — hospitals were for the indigent. Since the nation’s first hospital — Pennsylvania Hospital, where Rush worked — was not accepting Yellow Fever patients to prevent contagion, the College asked the city to create a new “large and airy hospital” for them. (Soon after, one was created at Bush Hill, a mansion on the outskirts of town.)

To prevent catching the fever, the College recommended avoiding “all fatigue of body and mind,” as well as “standing or sitting in the sun” or in a “current of air.” While the fever was assumed to be airborne — carried by “miasma” — the doctors believed that building fires to change the air would be ineffectual, but burning gunpowder could work. In the aromatherapy department, citizens were soon eating or rubbing themselves with garlic, smoking constantly or chewing tobacco, and even dipping pieces of rope into tar to wear around their necks.

Rush wrote to Julia that he hoped the recommendations would “do good, but I fear no efforts will totally subdue the fever before the heavy rains or frosts of October.” Until then, he asked her to pray for him. “I hope I shall do well,” he said. “You can recollect how much the loss of a single patient once a month used to affect me. Judge then how I must feel in hearing every morning of the death of three or four!”

Rush was now working ridiculous hours and making little progress — patients continued to die. He asked Julia to tell the children he loved them. The stories that circulated were more and more shocking; publisher Mathew Carey reported that “a man and his wife, once in affluent circumstances, were found lying dead in bed, and between them was their child, a little infant, who was sucking its mother’s breasts. How long they had lain thus, was uncertain.” Rush was having the hardest time watching young people, the age of his own children, die. He was spooked by the image of “a solitary corpse” lying across the seat of a horse-drawn carriage, with nobody attending its progress down the street.

With many doctors gone from town, he consolidated a small team he could count on: a young doctor he had trained, Caspar Wistar, two apprentice physicians, his household servant Marcus Marsh, and his mother and sister Rebecca, who insisted on remaining behind to take care of him as he took care of the city. And he began treating the fever with the common remedies: bark, wine, blistering, cool baths. But they didn’t work.

So, on September 3, he began trying a more aggressive regime, adding purges, using salts and crème of tartar. When they were “ineffectual to open the bowels,” he turned to small amounts of calomel, mercury chloride, and jalap, the Mexican tuber, downed with some “chicken water or water gruel.” This “mercurial antidote” seemed promising, so he recommended it to others — including fellow physicians who were ill.

Each day Rush was astonished to be still alive. Morning prayers had never seemed so moving and resonant, as he did them on his way to absurdly early house calls. “The delay of a minute,” he wrote Julia, “seems a year to a patient after a physician is sent for.”

For the next few days, he was sure his “mercurial antidote” could be the cure for everyone. But other physicians were skeptical — some, to his frustration, would even “rail” against his “new remedy.” While some of this was just unfriendly competition and jealousy of his prominent position in the medical community, there was disagreement with Rush on purely medical grounds. Some physicians said that his treatments were too aggressive and risky. They grew only more convinced when, once Rush realized purges alone weren’t stopping the disease, he added light bloodletting. And then when that didn’t work, he purged and bled more aggressively than ever before.

Purges and bloodletting were standard treatments of the day (and continued to be for decades after). And it was not unusual for a physician with a failing treatment to explore whether a higher dose might work, especially in a dire situation. And this situation was beyond dire — it was turning into a terrible epidemic.

Rush came across an old bound manuscript Franklin had given him, in which the Virginia doctor John Mitchell chronicled yellow fever epidemics in 1737 and 1741. Mitchell claimed that in certain yellow fever cases, he tried bleeding and purging even when the patient already had a somewhat faint pulse—regardless of the fact that bleeding was generally thought of as a way to reduce a pulse that was too strong. Instead of making these weakened yellow fever patients worse, however, the bleeding seemed to make them better. This convinced Rush that such measures were worth trying, however counterintuitive they were. (And while he didn’t say so, the fact that the manuscript was from Franklin’s library probably felt like divine intervention.)

So, when weaker treatments failed, Rush tried more aggressive purges and took more blood. Patients were now panicking at the first sign of anything they thought might be yellow fever, so even before they developed yellow skin and black vomit, he used light purges and bloodletting as preventive measures (paired with careful attention to the patient’s nourishment and cleanliness).

Physicians who disagreed with him used different courses of treatment; most tried purges, fewer of them bloodletting. Two who doubted Rush, Dr. George Stevens and Dr. William Currie, published a pamphlet recommending nothing more than fresh air, mild purgatives, and the opiate laudanum or ammonia to encourage perspiration. Whenever Rush heard about patients who had died after relying on the milder treatments in this pamphlet, he became angry that they hadn’t listened to him and at least tried bloodletting.

Of course, no one really knew how to prevent or treat yellow fever. (Even today, no treatment reliably targets the yellow fever virus. Some recover on their own while being kept hydrated and comfortable, and the rest die.) They also didn’t know the true source of the disease — it was carried by infected mosquitoes. Instead they debated angrily if it was contagious or not, and whether it had been brought into Philadelphia by boat or was local in origin.

In the absence of actual information, partisan rancor filled the void, turning the debates into a nasty zero-sum game.

Medical treatments became political. When a doctor who disagreed with Rush’s methods successfully treated Hamilton, his regimen was called the “Federalist cure,” while Rush’s was “Republican.”

Thomas Jefferson assumed Hamilton’s illness had been caused by sheer fear. If Hamilton was in danger at all, he wrote to James Madison, “he puts himself so by his excessive alarm. He had been miserable several days before from a firm persuasion he should catch it. A man as timid as he is on the water, as timid on horseback, as timid in sickness, would be a phenomenon if his courage, of which he has the reputation in military occasions, were genuine. His friends, who have not seen him, suspect it is only an autumnal fever he has.”Then it got political. Alexander Hamilton (Rush’s “frenemy” and neighbor) and his wife, Elizabeth, both became ill, and chose to be treated by Dr. Stevens.

Whether the Hamiltons actually had yellow fever cannot be proven. But on September 11, after they felt better, they touted Dr. Stevens’s milder course of treatment in the newspaper. Hamilton wrote a public letter saying Stevens’s “mode of treating the disorder varies essentially from that which has been generally practiced — And I am persuaded, where pursued, reduces it to one of little more than ordinary hazard.” The Federalist press praised Stevens and called his treatment the “Federalist cure.”

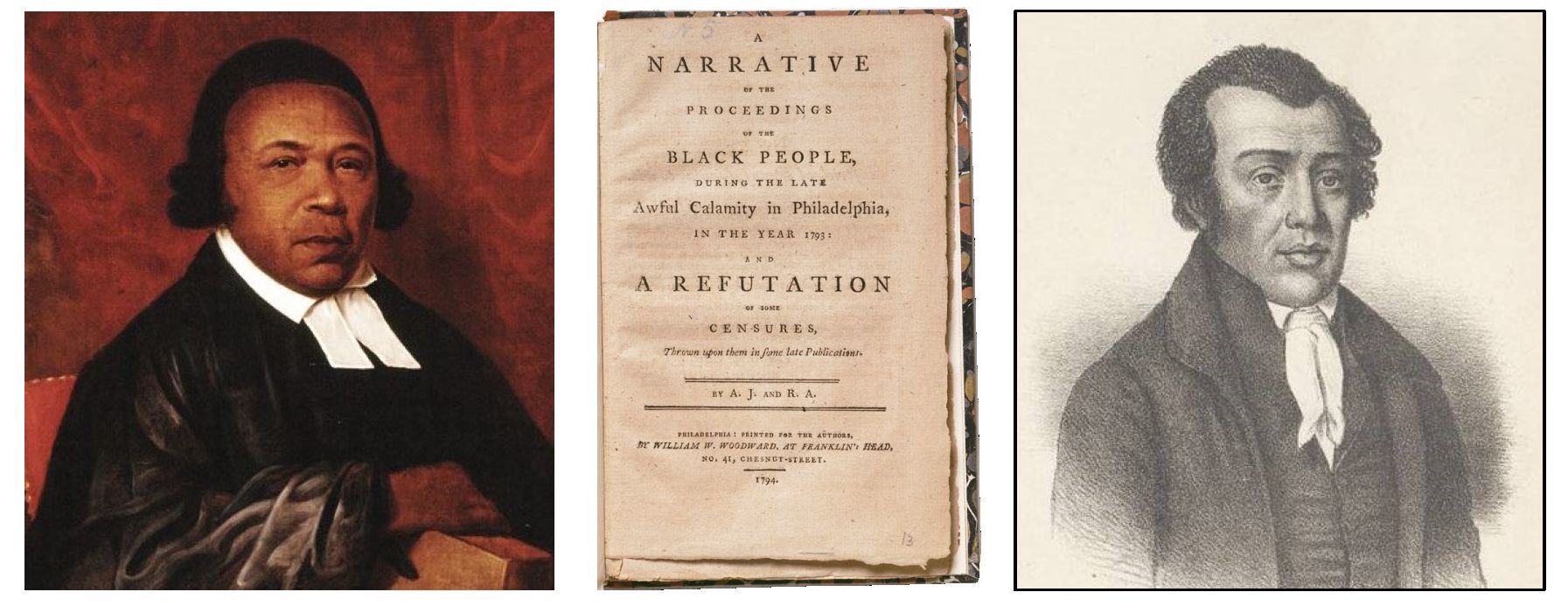

On the very day Hamilton’s letter came to light, September 11, an announcement appeared on the front page of several local papers from black leaders Absalom Jones and Richard Allen—clergy friends of Rush, who he had been helping build the nation’s first free black church. Since many of the city’s white physicians and nurses had fled, Jones and Allen wanted people to know the black community stood ready to help: “As it is a time of great distress in this city, many people of the Black colour, under a greatful remembrance of the favour received from the white inhabitants, have agreed to assist them as far as in their power for the nursing of the sick and burial of the dead.” The ad listed the home address for both reverends.

Rush had encouraged Allen and Jones to offer their services. In a letter dated “September 1793,” he wrote them,

From your sincere friend

B Rush

At the time, Rush believed it was a medical fact that black people were immune to yellow fever. The insight was not his own, but one found in the authoritative treatise on Yellow Fever in America, a thirty-page account written in 1753 by South Carolina physician John Lining, published by the Philosophical Society in Edinburgh (where Rush had attended medical school). In it, Lining noted that everyone in Charleston, where he practiced, had contracted the fever except for “young children ... who had formerly escaped the infection” (so they had developed resistance) and, he noted, “there is something very singular in the constitution of the Negroes, which renders them no[t] liable to this fever; for though many of these were as much exposed as the nurses to the infection, yet I never knew one instance of this fever amongst them.” Lining found this particularly surprising because African-Americans “are equally subject with the white people to the bilious fever,” the more common seasonal virus.

The day after Jones and Allen’s advertisement, Rush dashed off a letter to the College of Physicians to justify his new methods. (“I have bled twice in many, and in one acute case four times, with the happiest effects.”) Then, impetuously, he wrote to the Federal Gazette, offering detailed medical advice to the entire city. He shared his controversial “antidote,” which was still only days old and had been tested on a few dozen patients. He suggested that if patients were unable to be seen by the city’s few remaining physicians, they could arrange for the purges and bloodletting themselves.

His writings had an immediate impact. As George Washington’s personal secretary, Henry Knox, informed the president several days later, “Doctor Rush’s success…is great indeed. I understand that he has given his medicine to upwards of 500 patients. He does not pretend to say they have all had the yellow fever but many undoubtedly had, and he lost only one since he adopted his new mode. He has acquired great honor in visiting every body to the utmost of his power. but his applications have been so general that it was utterly impossible to attend to all of them. But he directs the medicine and the apothecaries [prepare] it.”

On September 12, Rush was up at six a.m. scribbling a note to Julia. “After a restless night,” he wrote, “I am still alive and preparing for the awful duties of the day. Yesterday exceeded any of the days I have seen for distress and death in our city… I send you these few lines only to let you know that I am still wonderfully supported in mind and body, but that I stand in greater need than ever of the prayers of all good people.”

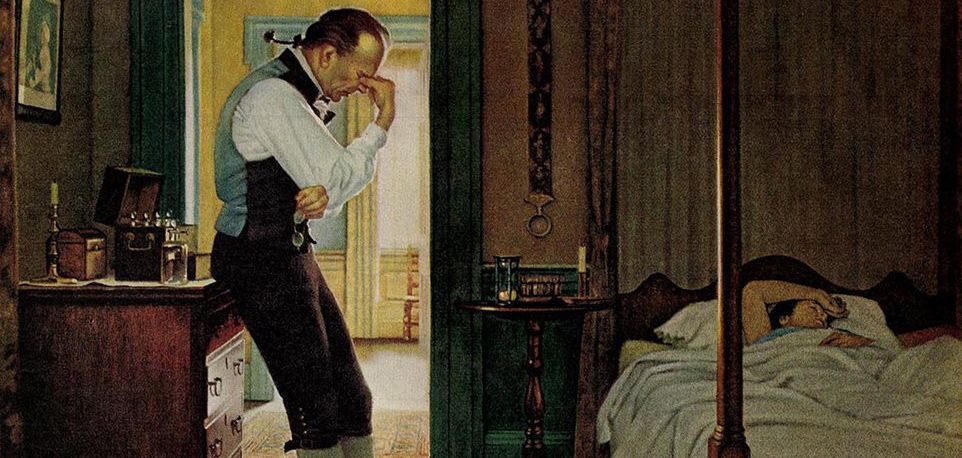

Just a day or two later, however, people would start saying Dr. Rush looked a little yellow himself. “My eyes are tinged of a yellow color,” he admitted. “This is not peculiar to myself. It is universal in the city.” And the next day he had his first attack of the fever.

His own treatment was administered to him at once. He was given purgatives and then bled and proceeded to convince himself he was cured. He had been living on two hours of sleep a night. He was physically wasted and cycling from buzzy excitement to depression as his beloved city experienced a disaster to match any biblical plague.

In the meantime, black aid workers were now roving the death-strewn streets of Philadelphia, asking how they could help. They carried bodies to the graveyard — the old plague phrase “bring out your dead” was most likely heard from workers helping Jones and Allen — and Rush taught some of them basic nursing (and lancing) procedures.

They witnessed heartbreak every day. Once Allen was called to a woman’s house to get her body for burial. “On our going into the house, and taking the coffin in, a dear little innocent accosted us with — ‘mamma is asleep — don’t wake her!’ But when she saw us put her into the coffin, the distress of the child was so great, that it almost overcame us. When she demanded why we put her mamma in the box, we did not know how to answer her, but committed her to the care of a neighbour, and left her with heavy hearts.”

Allen would also never forget the racial aggression toward the black aid workers. “A white man threatened to shoot us, if we passed by his house with a corpse. We buried him three days after.”

Rush’s letters to Julia in late September were a jumble of reports on his own health and death tolls: “among the late dead are our neighbor Thos. Anthony, Mr. Walker, Mr. Ketland’s friend, all Ross the blacksmith’s family. . . Near twenty persons have died in Pear Street alone.” On September 23, at about twelve-thirty p.m., Rush lost his first staff member: “my dear and amiable pupil Johnny Stall breathed his last.” His sister, Rebecca, was also ill with the fever, and refused to take any treatments; she died on October 1st.

And during that intense week, Rush also realized he had been tragically incorrect about black immunity to the fever. “The Negros are everywhere submitting to the disorder,” he wrote Julia. “Rich. Allen. . . is very ill. If the disorder should continue to spread among them, then will the measure of our sufferings be full.”

Then Rush, who had been feeling better, had a massive relapse of the fever. At one a.m. on October 10, he was “attacked in a most violent manner with all the symptoms… Seldom have I endured more pain. My mind sympathized with my body… At 2 o’clock I called up Marcus and Mr. Fisher [an apprentice], who slept in the adjoining room. Mr. Fisher bled me, which instantly removed my pains, and then gave me a dose and a half of the mercurial medicine. It puked me several times during the night and brought off a good deal of the bile from my stomach.”

Rush spent the next day at home, and when his pain returned, he asked to be bled again. The next night he grew still sicker and had what he called a “fainty fit.” He was in bed for several days before he found himself regaining his strength and decided to start seeing patients again. On the morning of October 21, he arose thrilled at how nippy the weather was. Perhaps the only thing he and his fellow physicians agreed on was that fall weather would quash the epidemic—although all were wrong about why, based on their respective incorrect theories on how the disease was spread. (In fact, mosquitoes stop breeding in the cold.).

People all over the country had read about Rush’s bravery and commitment. Julia wrote “there is great sympathy in New York in your sufferings,” and a friend of hers there had told her “you are all but prayed for by name in most of the churches.” But in Philadelphia he felt like a pariah, because too many of his fellow doctors had refused to follow his advice about treatments. As Rush was the most important professor at the nation’s first medical school—at the newly renamed University of Pennsylvania—this confused and pained him.

Several days later, Richard Allen, who had recovered, and Absalom Jones came to the house to visit. After most of the white doctors had stopped being able to treat patients, they had taken it upon themselves to procure “the printed directions for curing the fever,” and then had gone “among the poor who were sick, gave them the mercurial purges, bled them freely.” They had, in their own estimation — and Rush agreed, as he wrote Julia — “by those means save[d] the lives of between two and three hundred persons.”

Just as Governor Mifflin announced that the epidemic was officially over in early November, journalist Mathew Carey published A Short Account of the Malignant Fever Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia. It refueled every fight that had just died down in the medical and political communities and instigated a new one between the races: Carey reported that the black men and women who had been so heroic had also overcharged many people and plundered some of their houses.

No doubt Rush encouraged the book-length response to it written by Absalom Jones and Richard Allen. Their book, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications, was published on January 24, 1794, and became a landmark in many ways. It was the first copyrighted book ever written by African Americans, and it was also the first time black authors challenged a prominent white journalist — and some of Philadelphia’s more racist (yet unnamed) citizens— in print.

The book showed exactly what Jones and Allen and other black Philadelphians had done during the yellow fever epidemic in great detail. The two of them had handled a great many of the city’s burials, and they knew the location and cost of every coffin. After Rush got sick, they had handled much of the bleeding and purging around the city and had coordinated nursing efforts.

“We feel a great satisfaction in believing, that we have been useful to the sick,” they wrote, “and thus publicly thank Doctor Rush, for enabling us to be so. We have bled upwards of eight hundred people, and do declare, we have not received to the value of a dollar and a half, therefor: we were willing to imitate the Doctor’s benevolence, who sick or well, kept his house open day and night, to give what assistance he could in this time of trouble.”

They admitted that, among all races, some people had overpaid for services out of desperation, and even that some dead people’s homes had probably been looted. But they expressed outrage that anyone would suggest that mostly black people had done any of this — because they hadn’t.

Within six months of the book’s publication, Jones and Allen had opened not only the first black church in the nation’s capital but the first two. The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas opened on July 17 under Jones’s supervision. (Rush presumably was there — according to church records, he paid to reserve his own pew, and the visiting white Episcopal pastor, Samuel Magaw, thanked the doctor for helping him with his sermon.) But by then, Richard Allen had decided he wanted to have his own congregation with a different denomination. After further fund-raising, he bought a building at the corner of Sixth and Lombard streets and turned it into the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), which opened on July 29.

That summer Rush published his own 363-page opus on the epidemic: An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as It Appeared in the City of Philadelphia in the Year 1793. After 337 pages of sober analysis, Rush shared his own journey through the fever:

“Narratives of escapes from great dangers of shipwreck, war, captivity, and famine, have always formed an interesting part of the history of the body, and mind of man. But there are deliverances from equal dangers, which have hitherto passed unnoticed; I mean, from pestilential fevers.”

This version was darker than the one he told Julia in his letters; he hadn’t wanted her to know just how bad things were. Rush also brought the reader up to date on his health. “My convalescence was extremely slow,” he wrote, but the “early warmth of the spring, removed those complaints, and I now enjoy, through divine goodness, my usual state of health.”

Rush made a theatrical finish. “But wherewith shall I come before the great father and redeemer of men,” he asked, “and what shall I render unto him for the issue of my life, from the grave?”

He paused. Then: “Here all language fails.” And finally, a quote from the Scottish poet James Thomson: “Come then, expressive silence, muse his praise.”