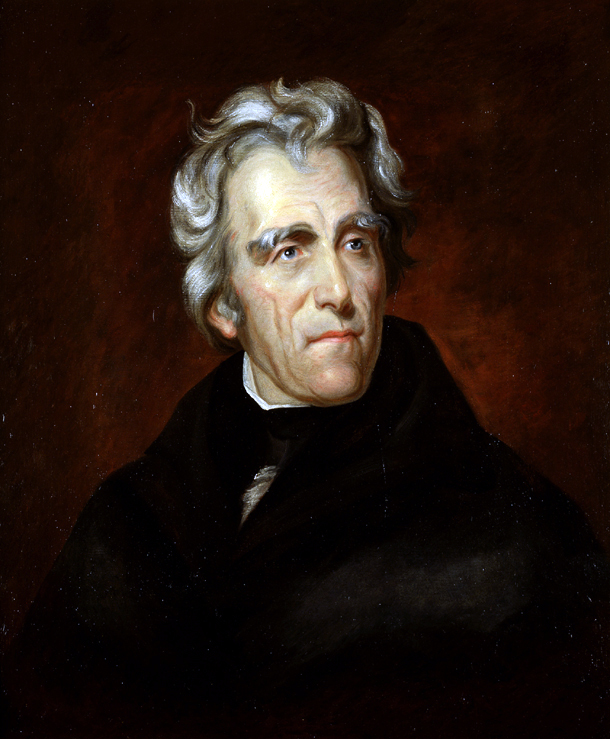

Was he the era’s greatest Democrat or its elected autocrat? A hero or a scoundrel? Balancing Andrew Jackson’s legacy is a problematic exercise, complicated by his many contradictions.

-

November/December 2022

Volume68Issue6

Editor's Note: David S. Brown teaches history at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. He is the author of The First Populist: The Defiant Life of Andrew Jackson, from which this essay was adapted.

Andrew Jackson, the first president to be born in a log cabin, to live beyond the Appalachians, and to rule, so he swore, in the name of the people, refuses to fade away. Controversial in his own day, he remains unrepentant.

Some identify Jackson as the common man’s crusader in chief, a defender of farmers and wage-earners who, with a single lethal veto, is said to have saved the republic from a rapacious Money Power by quashing a government-chartered national bank that catered to economic elites. Others are far less willing to accept as a hero a slaveholder, an architect of Indian removal, and a critic of abolitionism. The epithets “racist,” “white nationalist,” and “ethnic cleansing” now vie with the Bank War and the Battle of New Orleans in reckoning with Jackson’s fluctuating reputation.

On one point, however, all sides can perhaps agree—Old Hickory, the first president to come from neither Virginia nor Massachusetts, broke up the long train of coastal executive aristocrats, embodying in his improbable ascent the promise of western frontier peoples negotiating a natal age of expanding political participation.

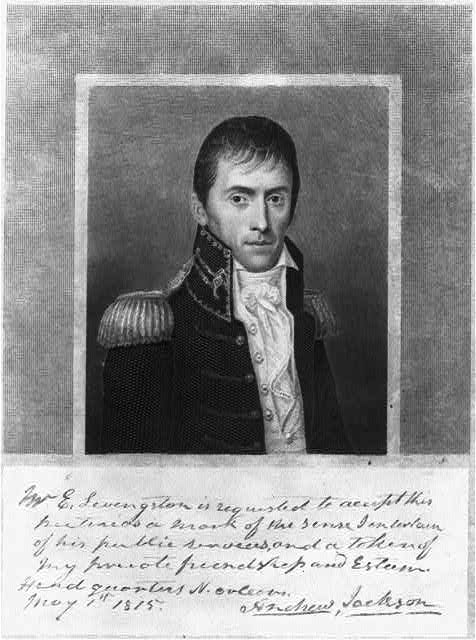

More precisely, Jackson, a cotton nabob, master to hundreds of slaves in several states, in fact straddled two sections. As the country’s fifth Southern president, he aligned as well with the interests of an entrenched squirearchy, having sought entry into its environs from an early age. The orphan of impoverished Scots-Irish immigrants, Jackson strove to ape the gentry and become a gentleman among Tennessee’s self-anointed blue bloods. Along the way, this parvenu acquired a plantation, bought and sold slaves, engaged in land speculation, and bred racehorses. He pushed for military appointment, fought in class-affirming duels, and adopted a distinctly southern notion of honor that elevated the landed nobility over mere citizens.

Two reflections on an aged Jackson by British women—the visiting writer Harriet Martineau and the expatriate actress Fanny Kemble—offer contrasting but retrospectively revealing judgments. The former depicted the general as fundamentally ill-informed and uneducated, a poorly postured eminence betrayed by a trace of depression:

Kemble more amiably emphasized the courtly, martial side of her subject, whom she described as:

Jackson, of course, cultivated both impressions. While Martineau stressed the unlettered side of her subject, Kemble, once described by the writer Henry James as having “seen everyone and known everyone . . . in two hemispheres,” noted a natural patriarch, an air still more abundantly asserted by a cotton oligarchy committed to the appearance of chivalry in the practice of slavery.

Martineau highlights the surprising frailty of Jackson through most of his life. The general’s cadaverous physique idled in pain and discomfort; his many ink-stained letters are filled with references to internal afflictions, ailing teeth, and weak lungs. But he was hardly a hypochondriac. Jackson paid with his body for the chain of military campaigns—from the American Revolution to the War of 1812 to the subduing of the southern Indians—and ritual affairs of honor that secured his reputation. He suffered from dysentery, dyspepsia, and bronchiectasis; contracted chronic diarrhea; battled pulmonary infection and malaria; and may have had intestinal parasites. Two bullets were lodged in his body - one from a duel and the other during a brawl. The cavities were prone to infection, and the lead from them leached steadily over the years into his system. Jackson bore the aches and inconveniences of these infirmities for much of his life, and they must have exacerbated his tendency to be quick-tempered.

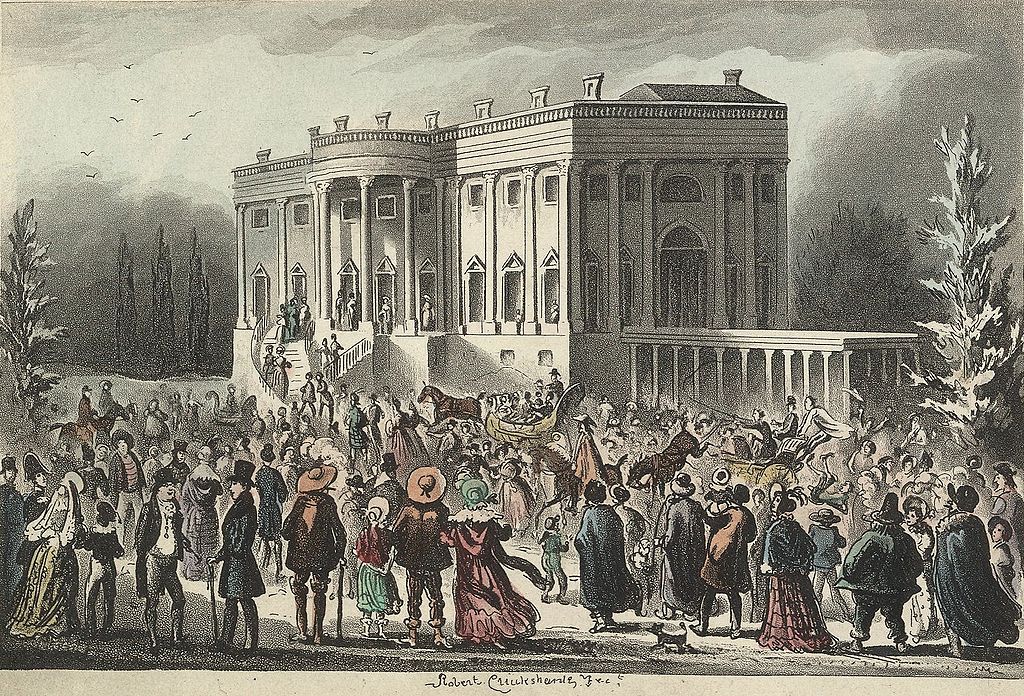

Jackson’s splenetic cast of mood and attitude, “formidable” in Martineau’s rendering and “very obstinate” in Kemble’s, is perhaps Jackson’s defining attribute. He could be a devout and fierce hater, inspiring in turn the devout and fierce hatred of others. A series of pre-presidential episodes—ordering the deaths of deserting militiamen, killing a Tennessee dandy in a duel, and overseeing the executions of two British subjects while commanding a U.S. army sweeping illegally through Spanish Florida in pursuit of Seminoles—prefaced a sequence of equally astonishing presidential actions. These included the violent removal of Indian people from their ancestral homes; asserting his supposed right to enforce or ignore Supreme Court decisions; and firing off more executive vetoes than had all of his predecessors combined. Cocksure in the extreme, Jackson found both essence and consequence trafficking in a world of enemies he had made, cultivated, and, over the years, assiduously accumulated. This congenital unquiet helps to place a couple of other antecedents in context, for Old Hickory was also the first president to be targeted by a would-be assassin and the only one to suffer a senatorial censure.

Drawn to these and other rare episodes of presidential Sturm und Drang, we too casually discount Jackson’s real skills as a statesman.

More polished and lawyerly than many have suggested, he often read the public far better than Congress did. None of his vetoes were overridden; an unprecedented third term was his for the asking. A number of Washingtonians were surprised when they first encountered the legendary general, expecting something of a savage from the wild backwoods. A bemused Jackson—like a wry coonskin-cap–wearing Benjamin Franklin playing the rustic in Paris—enjoyed the juxtaposition. An underrated politician, he knew well the length and limits of his personal popularity; easily courted the sudden electoral prominence of western constituencies; and managed to combine an aristocratic persona with a less-posh public face.

Balancing Jackson’s legacy is a problematic exercise, complicated by many contradictions. Was he the era’s greatest Democrat or its elected autocrat? Should he be remembered primarily for the Bank War—the fight against economic privilege, or for his determination to extend white privilege (and slavery) into the Gulf Coast states? And to what extent, if any, should he be evaluated from our era’s standards? “At one time in the history of the United States,” a biographer accurately enough reminds us, “Andrew Jackson . . . was honored above all other living men.” It is also true that many of his contemporaries thought the general petty, narrow, and excessively partisan on behalf of agrarian and frontier communities. The perceptive French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville captured some of this in the first volume of Democracy in America (1835), noting that “Jackson is the spokesman of provincial jealousies; it was decentralizing passions . . . that brought him to sovereign power.” Tocqueville recognized the reciprocal relationship that linked the seventh president to his supporters: “He yields to its intensions, desires, and half-revealed instincts, or rather he anticipates and fore-stalls them.” On the other side of the social divide, so the Frenchman insisted, “all the enlightened classes are opposed to General Jackson.”

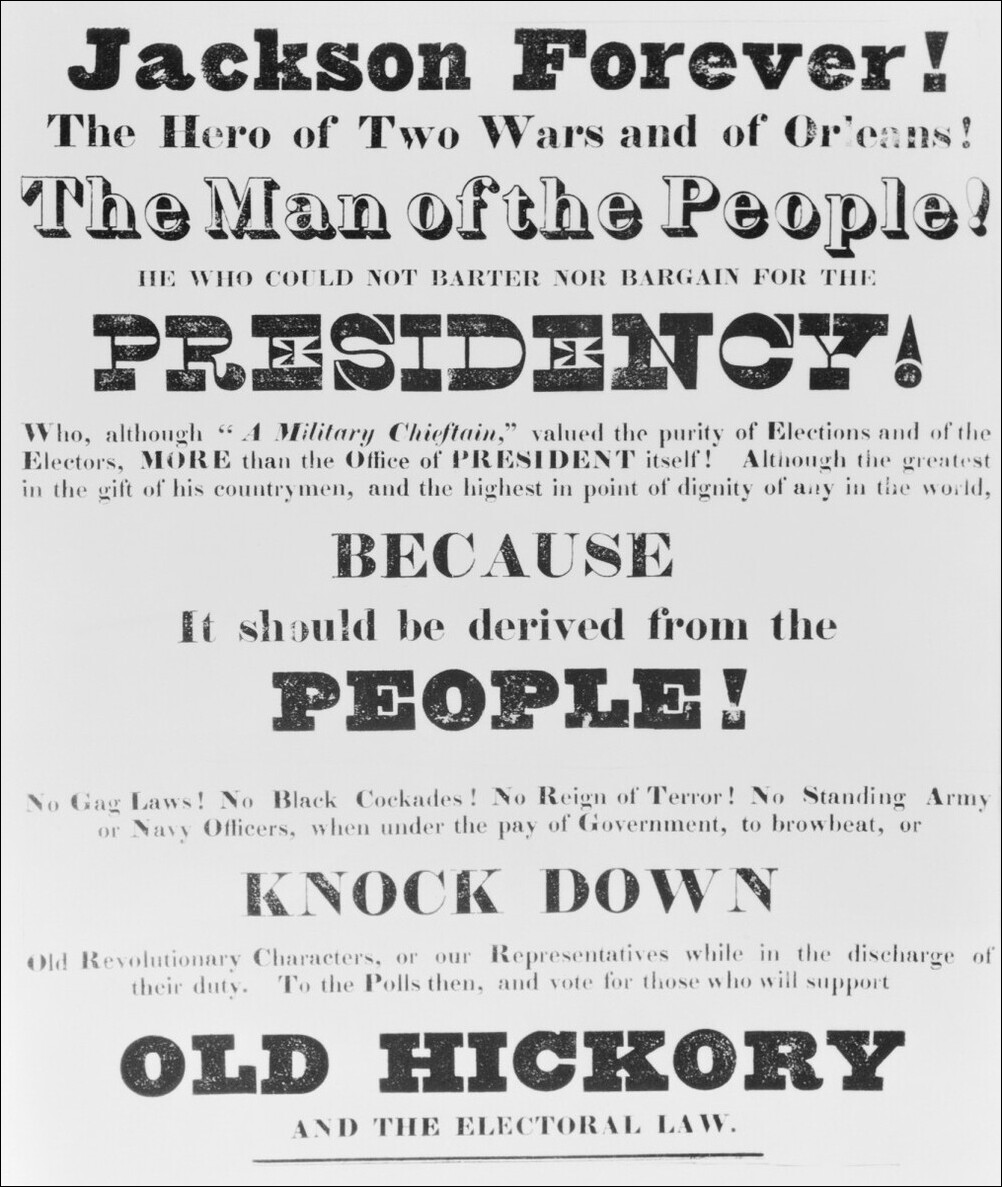

There is consensus among historians that Jackson, as much as any president, imposed his priorities upon the nation. This makes him an especially relevant figure to revisit today when many people, perhaps not so removed from Tocqueville’s thinking, see populism as a challenge to liberal democracy. It is often asserted that an organized populist persuasion, as opposed to a mere expression or attitude of the same, first found traction in America during the late nineteenth century, and that the People’s Party (1890–1910)—Southern and Western defenders of agrarianism, railroad regulation, and monetary reform—advanced its most coherent vision. Its champion, three-time Democratic nominee for the presidency William Jennings Bryan (“the Great Commoner”), anticipated, so the narrative goes, future adherents of an anti-elite, culturally conservative, and blue-collar political faith. These included Louisiana senator Huey Long (Depression-era author of a notional Share-Our-Wealth program), Joseph McCarthy (demonizer of academics and Hollywood types during the Red Scare of the 1950s), and the segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace (a stalwart defender of white rights during the Sixties).

In our own time, populism has entered the mainstream, as in the democratic socialist Bernie Sanders’s Bryan-like anger at Wall Street and former president Donald Trump’s demagogic appeals to rural and Rust Belt voters. But Jackson, the product of an earlier vox populi upheaval, was the original one. He energized a mass movement targeted against an eastern ruling regime. He claimed to speak for the nation’s “farmers, mechanics, and laborers,” and he frankly distrusted experts, preferring his informal kitchen cabinet of advisors to administration officials. Not above demonizing bankers, abolitionists, and any political opponents, he ruled by agitating, confronting, and dividing. He was the original anti-establishment president.

The script being written today, that economic inequality, liberal elitism, and demographic change in America and elsewhere have encouraged a backlash reflected in the rise of charismatic- strongman leadership, applies to Jackson, as well. His several resentments—against the monetary dominance of the National Bank; a political system that routinely returned quasi-aristocrats to the presidency; and a Supreme Court that disagreed with him on the Indian-removal question—were shared by many Americans. The movers and shakers resented by Jackson and his supporters ministered primarily to an Atlantic Seaboard society, even as the Ohio and Mississippi valleys were rapidly growing. These regions, only just coming into their own, were soon to shake the electoral landscape. In the 1828 presidential contest, every trans-Appalachian state went for Jackson over the Harvard-educated incumbent, John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts.

In Jackson’s approach to the electorate, we see a number of precedents—the first populist president, the first executive to be selected (in the wake of suffrage extensions in state constitutions) by the franchise of white men from all classes, and the first to practice a politics of resentment against an entrenched gentry. A modern version of this is Ronald Reagan’s famous 1981 inaugural address attack on Washington politics: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem. From time to time, we’ve been tempted to believe that society has become too complex to be managed by self-rule, that government by an elite group is superior to government for, by, and of the people.” More recently, Trump told a Grand Rapids, Michigan crowd in 2019, regarding his critics, “They say they’re the elite . . . (but) we got more money, we got more brains, we got better houses and apartments . . . You’re the elite; we’re the elite.”

Jackson became the defining figure of his era—a hero, a scoundrel, and, to his enemies, a second Caesar. His ability to tap into the aspirations and estrangements of emerging constituencies outside the orbit of the Eastern mainstream remade the nation’s electoral map. Advancing groups in the Age of Jackson, exemplars of popular politics, were ready, in their plainspoken devotion, to make him the man-on-horseback apple of their eye.