McKinley and his secretary of war were accused of negligence and corruption in the conflict, including forcing soldiers to eat "embalmed beef."

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

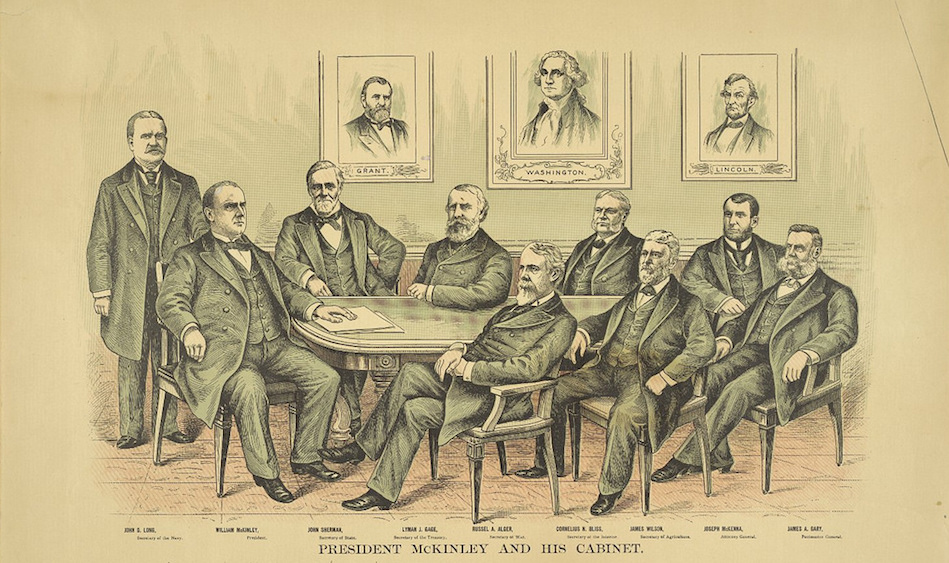

On September 8, 1898, Secretary of War Russell A. Alger formally petitioned President William McKinley for an investigation into the War Department's conduct of the war with Spain. For months Alger had been the target of a crescendo of criticism and verbal abuse arising out of the confusion that marred the American war effort from start to finish. The range of criticism is suggested in Alger's request that the inquiry examine such matters as mobilization, supply transportation, military contracts, all expenditures, orders emanating from the War Department--in short, everything connected with the army during the brief conflict except grand strategy and tactics.

McKinley quickly approved the request, and on September 24 he announced that a voluntary commission of military men and civilians would conduct the investigation. His first choice to head the commission, Lieutenant General John M. Schofield, suspected that the inquiry was a political ploy and declined to serve. McKinley then recruited General Grenville M. Dodge, a prominent Republican businessman and Civil War veteran, who had long been a friend and defender of Alger.

Alger was a poor choice to head the War Department. A former governor of Michigan and past commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, he had been picked purely for political reasons. Genial and self-confident, he knew nothing about the War Department, and during the year following his appointment he did almost nothing to prepare the army for a war whose coming he could hardly have failed to anticipate.

Admittedly, the task he faced was a gargantuan one. For decades the American people had badly neglected the army. By 1898 it was riddled with stuffy traditionalism, petty jealousies, and bureaucratic lethargy. The wonder is that it performed as well as it did and managed to reform itself pragmatically as the war progressed. Given the American military posture in 1898, it was all but inevitable that the war effort should have been marked by confusion and bungling. Of his own role in the disarray, Alger plaintively observed that “the life of the Secretary of War was not a happy one in those days of active military operations.”

Early in the war, McKinley began to suspect that Alger was an ineffective war minister—and so did the press and members of Congress. As early as May 18, the New York Times demanded that Alger be removed. But while McKinley lost confidence in him and consistently bypassed him in dealing with the army command, especially in matters of strategy, he retained him in office and publicly supported him.

The earliest indications that the outdated military system was in serious trouble came in July and August in the badly neglected medical department. Shortages, low priorities, poor distribution, nightmarish sanitary conditions, and epidemic tropical diseases mounted to inflict upon the army what one authority has called a “shattering medical disaster.” At Santiago, Cuba, the Fifth Corps suffered so badly from medical, supply, and morale problems that McKinley prepared orders to return the unit to the United States.

But before he could act, a group of officers in Cuba, including Theodore Roosevelt, circulated a round robin letter to newspapers at home in which they warned that the Fifth Corps “must be moved at once or it will perish” and accused the government of inefficiency and corruption. The letter so upset McKinley that he hastened the unit's return and billeted the sick and demoralized soldiers at a half-completed camp on Long Island, where new chaos quickly set in.

Alger bore the blame in the public's eye for this and other misadventures during the war. Even as the army began to pull itself together and overcome its early difficulties, he remained the butt of bitter resentment and outrage, within the army and without. Indeed, the term "Algeria became a popular synonym for incompetence. Despite a rising cry for his ouster, Alger refused to step aside, and McKinley did nothing to force him out of office. Probably the President realized that the firing of Alger could be construed as an admission that the administration had mismanaged the war.

As the Dodge Commission prepared to undertake its inquiry, McKinley gave it instructions akin to a charge to a grand jury:

He assured Dodge that he would put no limit on the scope of the investigation. Doubtless, McKinley was concerned about possible corruption and criminal negligence in the war effort, although his views as to what the inquiry might achieve in a positive way were vague.

In February, 1899, the Dodge Commission issued a nine-volume report, containing an enormous body of conflicting testimony and very little in the way of conclusions as to why the war had been mismanaged. The commanding general of the army, Nelson A. Miles, proved to be the witness most unfriendly to Alger and McKinley, with both of whom he had been at odds on practically everything throughout the war. Miles's testimony included a sensational charge that the War Department had foisted tainted and grossly inferior meat— “embalmed beef”—on the troops, and the commission spent long hours running down the charge before concluding that Miles could not substantiate it.

The report noted that many complaints and charges against the army were rooted in the rumors and tall tales that soldiers naturally circulate among themselves. The commission concluded, finally, that the army was guiltless of deliberate negligence and major corruption and that, under very difficult circumstances, it had probably done its best in the war.

As for Alger, the commissioners could not agree among themselves as to his competence or incompetence. The report acknowledged that he was an honest and hard-working official, but also noted that he had failed sufficiently to understand the need for efficiency and discipline in the army.

Thus cleared of official wrongdoing, Alger remained only a political problem for McKinley, rather than a possible source of major scandal embarrassment. Alger persisted in his refusal to give up his cabinet post, holding on with a tenacity that exasperated other members of the administration. When he finally resigned in August, 1899, it was under conditions totally unrelated to the war and the investigation.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.