Partisan politics, plus the media’s focus on Clinton’s personal life, created a presidency under siege and consumed by scandals—some serious, others trivial.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

By the 1990s, the “golden age” of presidential television had ended. While presidents since Dwight D. Eisenhower had enjoyed the ability to address the majority of the American public by appearing on the three commercial networks, William J. Clinton, known popularly as Bill Clinton, faced a very different media landscape as President. The number of households subscribing to cable television grew from 6 percent in 1969 to 68 percent by the end of the twentieth century. After CNN launched the model of twenty-four-hour news in 1980, its success inspired even more specialized news programming with competing all-news channel MSNBC and then Fox News coming on the scene in 1996.

Rather than simply reporting official statements from Clinton’s administration, a new group of press commentators, known as the “punditocracy,” spent hours examining behind-the-scenes White House operations.

Clinton frequently used this environment to his advantage by carefully cultivating his celebrity through appearances on CNN, MTV, and other outlets. But the media’s focus on Clinton’s personal life, as well as his partisan opponents’ determination to bring his administration under investigation by any available means as a political tactic, created a presidency under siege and consumed by scandals—some serious, others trivial.

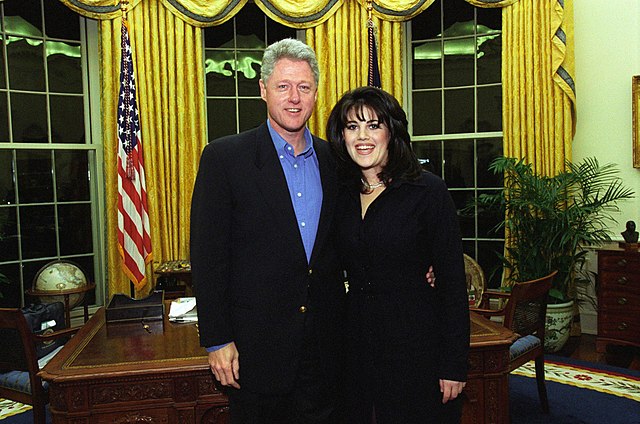

The inclination to try to turn a president’s personal transgressions into breaches of law reached a peak during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, one that ultimately resulted in a House vote to impeach a president for only the second time in history. Yet while the Impeachment Inquiry revealed that the President had lied and committed marital infidelity, it never proved that he had committed a “high crime” that warranted his removal from office.

Whitewater

Having seen Colorado Senator Gary W. Hart’s presidential campaign derailed in 1988 by accusations of adultery, Clinton understood that issues he had skirted in Arkansas—notably marital infidelity—could derail his national campaign, so his War Room kept opposition files on potential accusers and prepared to discredit them quickly. This strategy succeeded with regard to accusations of the President’s affair with Gennifer Flowers during his Arkansas governorship.

But, during his campaign and early presidency, Clinton encountered unexpected questions about Hillary Clinton’s legal career and their joint Arkansas real estate investments that tangled the President in yet more difficulties.

In March 1992, just after the War Room fought through the Flowers situation and questions of draft dodging, a New York Times article raised a question about the relationship between the Clintons and their friends and business partners from Arkansas James and Susan McDougal. At issue was a 1978 business deal in which the Clintons and the McDougals purchased real estate in the Ozarks called the Whitewater Development. Available records showed that the Clintons stood to benefit from their investment but risked very little if the venture did not succeed.

McDougal also remained a financial supporter of Clinton’s gubernatorial bid. Then, when Bill Clinton became Governor, McDougal hired Hillary Clinton and the Rose Law Firm, where she was a billing partner, to manage Madison Guaranty’s legal affairs. As the New York Times noted in its 1992 article, this tangled web of relationships raised “questions of whether a governor should be involved in a business deal with the owner of a business regulated by the state and whether, having done so, the governor’s wife through her law firm should be receiving legal fees for work done for the business.”

The Whitewater issue came back into the headlines following the 1993 suicide of Vincent Foster, Clinton's counsel (in December before the election, the Clinton's had Foster strike a deal to transfer all their interest in the Whitewater venture to James McDougal). When Bernie Nussbaum separated the files from Foster’s office, he was concerned as much about protecting documents from Hillary Clinton’s legal career at the Rose firm, which she was determined to keep private, as he was about protecting Foster’s privacy.

But such dogged pursuit of secrecy and the refusal to cooperate with law enforcement officials fueled the appetite for more “dirt” on the Clintons. Their claims to secrecy also allowed conservative media’s argument about Clinton conspiracies to gain traction rather than to disappear.

Clinton started the second year of his administration under investigation by a New York Republican, Robert B. Fiske, Jr., whom Independent Counsel Janet W. Reno had appointed as a special prosecutor tasked with examining Foster’s suicide and all issues related to Whitewater. Fiske first ruled out any misconduct or cover-up in the Foster suicide case by dismissing allegations of his murder.

However, the investigation took a turn in the summer of 1994 when the President signed an act reauthorizing Fiske’s investigation. The act required that a three-judge panel, not the Attorney General, appoint the Independent Counsel. Unhappy with Fiske’s report on Foster’s suicide, conservatives pressured the judges to replace Fiske with someone who would pursue the investigation more vigorously.

Ultimately, the judges decided on Kenneth W. Starr. A lawyer and former federal judge and U.S. Solicitor General under President George H.W. Bush, Starr was an active Republican and critic of President Clinton.

The Whitewater investigation resulted in sixteen convictions for charges that included fraud, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice and included the conviction of Webster L. Hubbell, a law partner of Hillary Clinton and former Clinton appointee to the Justice Department. It did not produce any evidence that either of the Clintons had engaged in wrongdoing, even if their actions raised some ethical questions. Ultimately, both James and Susan McDougal went to prison for fraud and conspiracy. Starr insisted that Susan serve in a windowless cell in hopes that a harsh punishment would make her turn on the Clintons. She did not.

Monica Lewinsky and Impeachment

On August 17, 1998, President Clinton addressed the nation and admitted to having “inappropriate relations” with a former White House intern, Monica Lewinsky. He emphasized that his answers in a previous deposition had been “legally accurate” but acknowledged that he had misled the American people and his family. Apologizing for “hurting” people, he ended his address with an adamant defense of his privacy. “I intend to reclaim my family life for my family,” he declared. “Even presidents have private lives.”

The case began not with Monica Lewinsky but with another woman who had alleged sexual harassment by the President. In May 1994, Paula Corbin Jones filed a federal lawsuit against President Clinton and an Arkansas State Trooper, Danny Ferguson, for a 1991 encounter between then-Governor Clinton and Jones in Little Rock, during which she alleged that Clinton made unwanted sexual advances toward her. Jones soon received encouragement from Clifford Jackson, a vocal conservative opponent of Clinton in Arkansas.

Bill Clinton testified in federal court about the charges raised against him by Paula Jones on January 17, 1998. Unknown to Clinton, Special Prosecutor Ken Starr had begun to look into newly acquired information about a matter that had nothing to do with real estate. He had received information from Lucianne S. Goldberg, a literary agent with conservative connections, that a disgruntled former White House employee, Linda R. Tripp, possessed information about an affair between Monica S. Lewinsky, a young White House intern, and the President. Hoping to trap Clinton in a lie during his deposition in the Paula Jones case, Starr asked Attorney General Reno to expand the Whitewater investigation to include charges of perjury and obstruction of justice.

The result was a legal spotlight focused for the first time on an American president’s sex life rather than on his official acts. Clinton, trying to navigate public opinion and guard his legal options, denied all stories about an affair with Lewinsky in ways that gave him legal flexibility. The day before delivering his annual State of the Union Address in January 1998, he turned to the cameras with the statement, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky.”

Hillary Clinton also joined the battle. She saved the President’s 1992 candidacy from accusations of sexual indiscretion with Gennifer Flowers by appearing with him on television, holding his hand, and defending their marriage. Now she appeared before the American people to charge that the accusations against her husband were just another chapter in a “vast right-wing conspiracy” that went so far as to blame the Clintons for murder.

Ultimately, the Clinton administration used its media savvy to turn the issue of sexual misconduct into different questions about a lapse in journalistic values and an expansion of conservative efforts to undermine the administration’s policy gains and the presidency. Their attack on Starr for pursuing a moralistic crusade rather than a legal investigation also proved effective. Trust in the news media plummeted. Only 11 percent of the public had a favorable view of Starr, and during a midterm election year, House Republicans nervously looked at polls that showed Clinton’s high approval ratings.

Nevertheless, the grand jury testimony in August 1998 forced the President to confront the probability that he would have to confess to an affair with Lewinsky. During his January deposition, he had said that he and Lewinsky never had “sexual relations,” which he later clarified such a definition as meaning only intercourse, not oral sex or other intimate acts. In an address to the nation following his deposition that August, Clinton claimed that he had not obstructed justice and that charges that he had done so arose from a “politically inspired lawsuit.” Sexual misconduct, he argued, was a personal failing, not a political abuse.

The Office of the Independent Counsel disagreed, seeing Clinton’s personal activities as disgracing the office of the presidency. Finally, in September 1998, Starr delivered the report of his investigation to the House of Representatives, which, to Starr’s surprise, voted to publish it without any member’s reviewing it in advance. The report concluded that Clinton’s behavior warranted impeachment in four categories: “perjury, witness-tampering, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power.”

In defending the President, House Democrats succeeded in making the Starr investigation itself the focus of debate. Rather than discussing high crimes and misdemeanors such as those of Watergate, the House ended up debating whether or not the President had lied about an affair, a sensitive issue inasmuch as many in Congress, notably House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA) and House Appropriations Committee Chairman (and Speaker-elect) Robert L. Livingston (R-LA), had been guilty of the same offense.

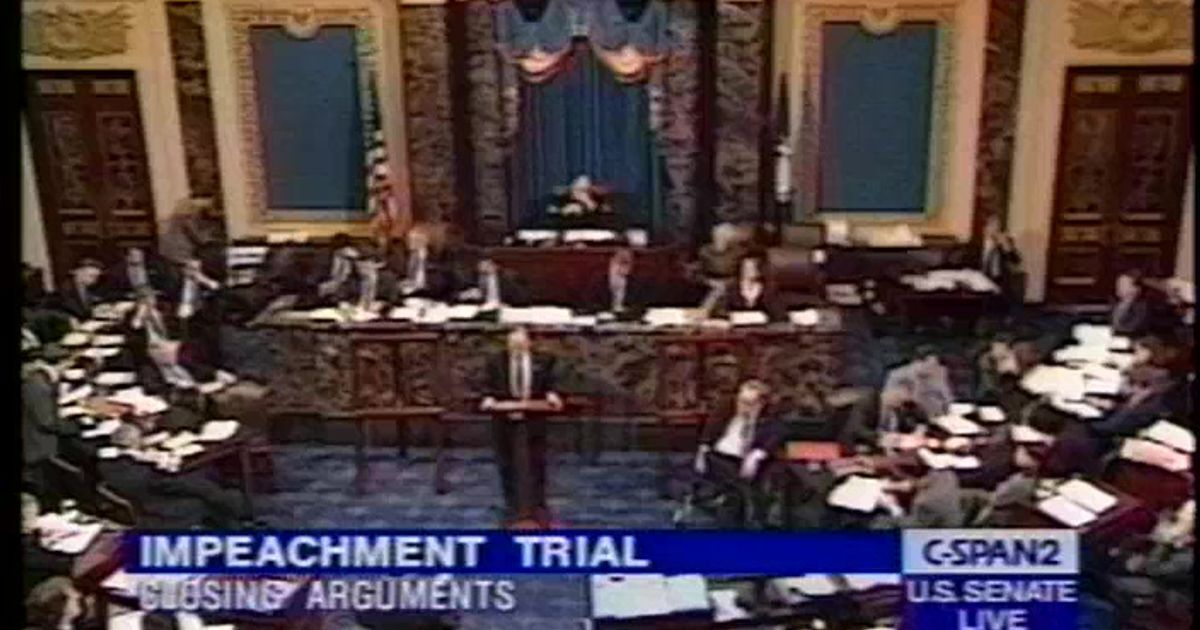

Nevertheless, Clinton’s defense could not stave off his impeachment. Emboldened with confidential reports about Juanita Broaddrick, a nursing home owner who alleged that Clinton had raped her in 1978, the full House voted along party lines to recommend that the Senate try the President for perjury and obstruction of justice.

Clinton’s Senate trial began in January 1999. But with public opinion on Clinton’s side, the body failed to produce a two-thirds majority to convict the President. Clinton’s approval ratings remained high throughout the entire length of the Starr investigation and congressional attempts to impeach and convict him.

But that was not the end of it. In April 1999, Judge Susan Webber Wright Wright held the President in civil contempt for having made “intentionally false” statements under oath during his January 1998 deposition in the Jones case. Her ruling, as one political scientist concluded, followed a “long judicial tradition in which judges avoid rendering decision in the midst of political controversy involving executive power, and in which their decisions come down after institutional conflicts between the President and Congress have been resolved.”

Ultimately, Clinton reluctantly agreed to the terms that would close the case for good. He would accept a five-year suspension of his license to practice law in Arkansas, pay a $25,000 fine, and admit that he “knowingly gave evasive and misleading answers” in his January 1998 deposition.

In one of his final acts in office, Clinton continued to generate controversy with a flurry of last-minute pardons. On January 20, 2001, Clinton issued 140 of them, including one to Susan McDougal and to two fugitives, Marc Rich and Pincus Green, wanted for tax evasion. The sheer number initially stunned the press. Public reaction was fierce, with former President Jimmy Carter calling the pardon of Rich “disgraceful.”

Although federal prosecutors concluded that Clinton had not violated the law, the pardons highlighted the ways in which the President courted controversy by trespassing the boundaries of ethical practices. Clinton’s presidency demonstrated that the acceptance of the earlier divide between public acts and private behavior had, by the 1990s, greatly narrowed in the world of American politics; private indiscretions could become political liabilities.

The Clinton administration revealed the degree to which questionable accusations can easily distract public officials’ attention from governing. A perhaps more serious consequence was the turn toward impeachment as a partisan tool rather than as a last resort to check illegal or out-of-bounds executive action.

Copyright © 2019 by The New Press. Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.