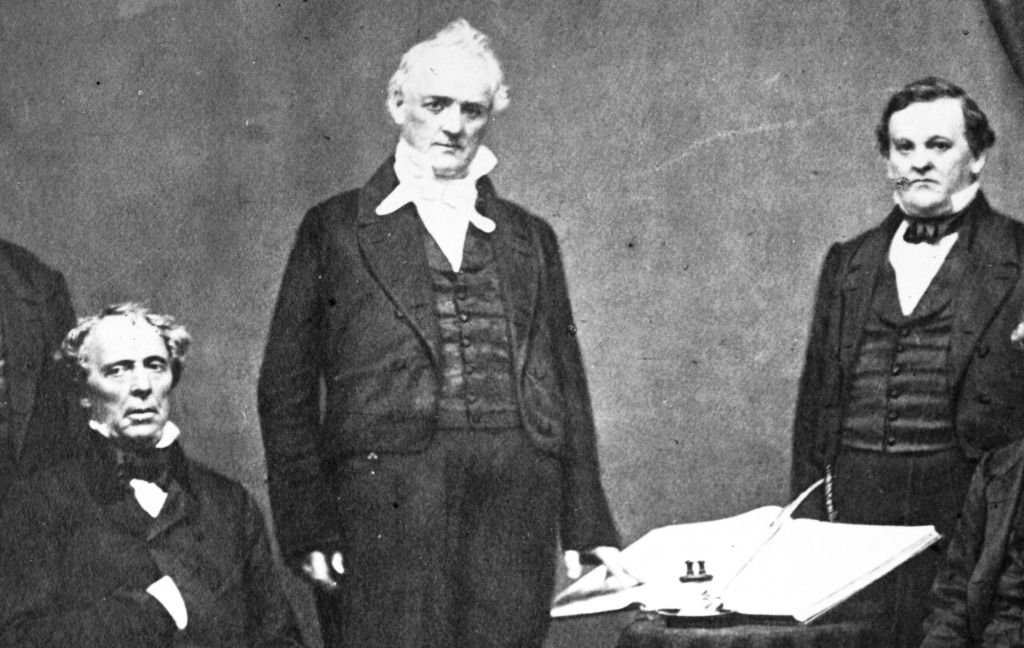

Did the James Buchanan know his Secretary of War, a future Confederate general, sent 110,000 muskets to armories in the South in 1860?

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

Many historians point to the presidency of James Buchanan as the nadir of antebellum public ethics. All of the trends of corruption at the lower ranks of the government seemed to culminate in three years, and the rate of exposure increased dramatically.

Republicans — the new Republican Party had become the nation’s second party by 1856 — and anti-administration Democrats alike fostered a multitude of congressional investigations of custom houses, navy yards, post offices, and the public printing. These revealed not only executive turpitude but also congressional corruption, not only activities during Buchanan’s term but sleazy practices during the entire 1850s and even earlier.

There is ample evidence of improper, if not outrightly illegal, Democratic actions to carry the elections of 1856 and 1858, actions of which Buchanan apparently was aware and in which some of his closest friends participated. Whether or not Buchanan directed or approved these activities, he apparently condoned them, for he made no attempt to stop them. Many of these would be exposed by the Covode Committee in 1860.

See also "Was The Secretary Of War A Traitor?" by W. A. Swanberg

The wide net cast by the Covode Committee did not cover all the abuses of Buchanan’s cabinet, nor did it raise the most embarrassing allegations against the men around the President. The most discomforting problems came with Secretary of War John B. Floyd. Buchanan’s egregious weakness in dealing with that cabinet officer and delay in decapitating him are as incomprehensible as they are reprehensible.

The Virginian Floyd does not appear to have profited personally from the War Department contracts or to have realized always how he was exploited. He was simply a careless administrator who tried too hard to please his friends and fellow party members. In 1858, for example, a congressional committee discovered some shady deals that Floyd had arranged to benefit his friends. When the army decided to build a new fort near New York City, Floyd asked some Democratic politicians there to find a suitable site. They quickly formed a syndicate, bought at a price of $130,000 some land which army engineers had earlier rejected, and sold it to Floyd for $200,000. Equally suitable sites were readily available at half the price.

It was also discovered that summer that Floyd had arranged the sale of the 7,000-acre Fort Snelling reservation in Minnesota to some Virginia friends for $90,000 when the property was worth considerably more.’’ Despite these exposures of incompetence and favoritism, Buchanan kept the hapless Floyd on.

Similarly, in the spring and summer of 1860, Congress in effect voted no confidence in the Secretary by attaching provisos to appropriations bills restricting his flexibility in awarding contracts. Yet another committee had learned of Floyd’s efforts to favor some Virginia builders with contracts for construction projects in Washington which the army was directing.

An open fight had developed between Floyd and influential senators over Floyd’s efforts to remove the army engineer in charge of that construction when he refused to deal with the Secretary’s cronies. Congress actually included in the appropriation for the project a stipulation that the engineer, Captain Montgomery Meigs, must supervise it in order to prevent Floyd from exiling Meigs to a barren army post in Florida. Floyd was totally discredited with congressmen of both parties. Still Buchanan kept him on.

In December, 1860, when the Buchanan administration was grappling with the tense secession crisis in South Carolina, the roof finally fell in on Floyd. Throughout Buchanan’s term, Congress had delayed and cut army appropriations. As a result, the contractors who supplied the army had, since 1857, been presenting bills to Floyd for the goods sold to the army before Floyd had the appropriations to pay them. Without authorization Floyd had signed these bills, thereby indicating the government intended to pay them, and the contractors, especially the New York firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, had used the endorsed bills as collateral to obtain bank loans.

Floyd simply assumed that Congress would make contingency appropriations for the army to meet these debts, but he had no guarantee. Buchanan learned of this practice in 1859 and was appalled. He reprimanded Floyd and ordered him to stop. But Floyd continued the practice, just as he continued in office.

Had the contracts been legitimate, Floyd would have had some justification. The army, after all, had to be supplied. Russell soon learned, however, that Floyd would sign anything, and he began to present fictitious bills for supplies never provided. Floyd continued to endorse them, and Russell continued to take out bank loans with the bills as collateral. There were eventually some $5,000,000 worth of bogus bills endorsed by Floyd in circulation.

Finally, the bankers refused to accept any more until the government paid up. Russell, whose demand for cash to repay old loans was insatiable, then learned of an Indian trust fund of $3,000,000 in negotiable bonds in the Interior Department. Spurned by the bankers, he now bribed the clerk in charge of the fund, a man named Bailey, to “loan” him the bonds temporarily with the Floyd-endorsed bills as collateral. Inevitably, the bonds were never returned.

Soon Russell would present Floyd with a phony bill any time he needed cash and then march over to the Indian Office to exchange the note for bonds which he then sold for cash. Incredibly, Floyd never seems to have known what was going on.

By December, 1860, Bailey was growing nervous. His accounts were due to be audited on January 1, and he was missing $870,000 in bonds.

On December 19 Bailey wrote a confession to Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson and sent a copy to Floyd. Buchanan learned of the whole affair on December 22 from Thompson. Thompson was livid with rage and had Russell arrested. He wanted Floyd dismissed, and by now even Buchanan thought the Virginian had to go. Still he hesitated. Unwilling to confront Floyd personally, he sent Thompson and Black to see Floyd, who was sick in bed. Floyd confessed all.

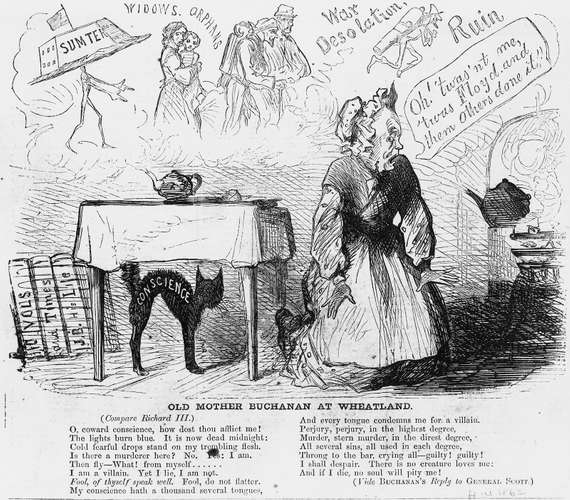

Buchanan, however, could not bring himself to fire the man. He asked Black to seek Floyd’s resignation: Black refused. Next, Buchanan persuaded Vice President John C. Breckinridge to ask Floyd for his resignation. Floyd indignantly refused and, despite his disgrace, continued to attend crucial cabinet meetings on events in the secession crisis. Buchanan appeared powerless. Finally, on December 29, 1860, Floyd resigned, using as his excuse disagreement with administration policy in Charleston harbor. The administration had reneged on pledges to South Carolina, he proclaimed righteously, and he refused to remain associated with such a dishonored regime.

Thus a man who had embarrassed and disgraced the Buchanan administration since 1857, a man whose ineptitude and conniving had been well publicized since at least 1858, finally left the cabinet. Buchanan’s weakness vis-à-vis Floyd, his apparent apathy about, if not obliviousness to, the appearance as well as the substance of impropriety in the conduct of government affairs, and his abdication of his responsibilities as chief administrator, reflect too well his role during his entire presidency.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.