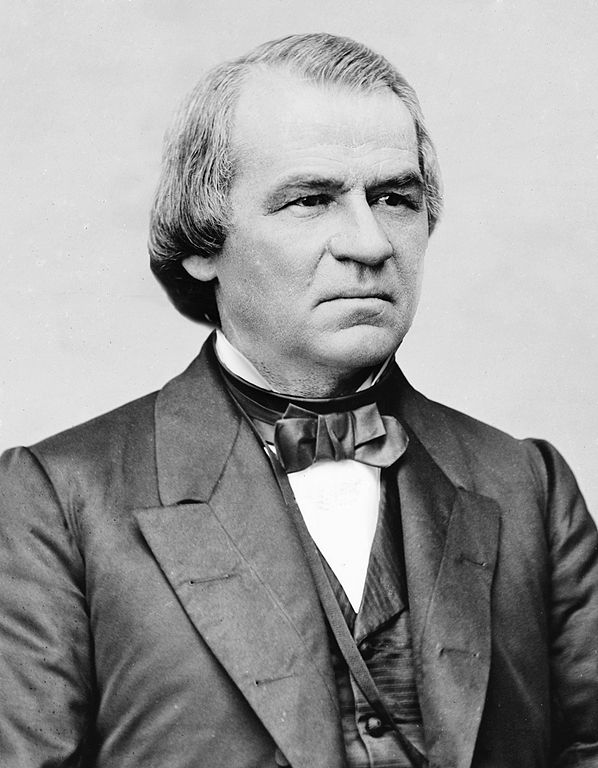

Although he was scrupulously honest, Andrew Johnson angered members of Congress by thwarting their plans for Reconstruction.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

The administration of Andrew Johnson, which began upon Lincoln's assassination in April, 1865, was predominantly concerned with redefining the status and rights of people, both black and white, living in the defeated Confederate states. The strong differences over racial policies between Johnson and his opponents in Congress lie outside the scope of this study. Johnson asserted an ideological and constitutional position of great importance on May 29, 1865, when he issued his Amnesty Proclamation. Under its terms, the President used his pardoning power to restore effectively the political and economic rights of virtually all white southerners.

Of concern here is not this stand by Andrew Johnson, but allegations that Johnson abused his powers as president by not executing the laws of Congress. Many important expressions of Johnson's defiance were made without notice to Congress or the public. Charges of such abuses of power formed the subject of extensive hearings in 1867 held by the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives. The committee heard more than eighty-five witnesses conversant with conditions in the South and enforcement of federal law and took 1,154 pages of testimony.

See also “They Impeached Andrew Johnson,” by David Herbert Donald

The first major case of failure to carry out the presidential duty of enforcing an act of Congress occurred on August 16, 1865. Congress, on March 3, 1865, had passed legislation creating the Freedmen's Bureau in the executive branch. President Lincoln signed the bill. Under its terms, “the Commissioner, under the direction of the President," was authorized to “set apart” for “loyal refugees and freedmen” for the period of three years “not more than forty acres of lands abandoned within the insurrectionary states.” This implied a promise of forty acres for about 20,000 freedmen families in the South.

On August 16, with notice only to the assistant commissioner of the bureau in Tennessee and to subordinate officers in the bureau headquarters in Washington (the commissioner was on vacation), Johnson ordered lands covered by the act of March 3 restored to a former landowner, B. B. Leake. On the back of a request for guidance in the matter, Johnson added that the “same action will be had in all similar cases." Almost casually, Congress's act was abrogated.

The appointive power lies with the president and extended, of course, over the Freedmen's Bureau. Investigating congressmen, however, charged that the power of appointment was abused when appointments were made for the specific purpose of frustrating rather than facilitating the enforcement of the law. Johnson replaced Thomas Conway, assistant commissioner for Louisiana, with James Scott Fullerton, and instructed Fullerton to report directly to him.

The President did this because Conway was prepared to execute the congressional land redistribution plan; Fullerton, as instructed, did not do so. The former assistant commissioner for South Carolina, Rufus Saxton, who had refused to resign and had to be fired so that lands could be restored, testified that a prominent white planter, William Whaley, “told me that the President had told him this property [held by freedmen] would be given up." That restoration of land was Andrew Johnson's intent was made completely clear when Freedmen's Bureau Commissioner O. O. Howard, in the company of Whaley, relayed the same message to the freedmen of Edisto Island.

By extending the pardoning power to include the restoration of lands that the freedmen were farming and by issuing orders to the bureau to evict freedmen from such lands, Johnson set aside the land provisions of the act of March 3, 1865. As House Judiciary Chairman George S. Boutwell stated, “In violation of law and without authority of law he [President Johnson] has restored them [abandoned lands covered by the act] to their former rebel owners.”

When Congress reconvened in December, 1865, it began work on a congressional form of Reconstruction. The program comprised the Fourteenth Amendment as well as a series of bills, including the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 that upheld land ownership by blacks and the construction Acts of 1867 that enfranchised Negroes in the South. In veto messages and other statements, Johnson vigorously spoke his ideological and constitutional objections to the congressional program. The bills were carried over his vetoes, and he was constitutionally required to execute them.

This he did not do fully. Two of Johnson's cabinet members repeatedly ignored the Test Oath Act of July 2, 1862, which required federal officeholders to affirm that they had not sympathized with, or contributed to, the Confederate cause. One cabinet member, Attorney General James Speed, did comply with the provisions of this law; but Hugh McCulloch, Secretary of the Treasury, abandoned the oath requirement and staffed departmental posts in the South with former Confederates, and William Dennison, Postmaster General, had by March, 1866, appointed to post office positions in the South 2,042 people, of whom only 1,177 were able to qualify under the Test Oath Act.

Not only were former Confederates unable to take the oath restored to office, but they could not be counted on to protect the lives of the black citizens of the South. One such incident was the New Orleans riot, which caused General Philip Sheridan to speak critically of the role of the President. Sheridan called the violence in the city, which resulted in the death of many black citizens by a marauding band that included some of the city's police, a “massacre.” Johnson's refusal to order an alert of nearby federal troops and his reliance instead on a pardoned Confederate mayor and the local law enforcement officials were regarded by the majority of a special congressional investigation committee in 1866 as abuses of powers by Johnson.

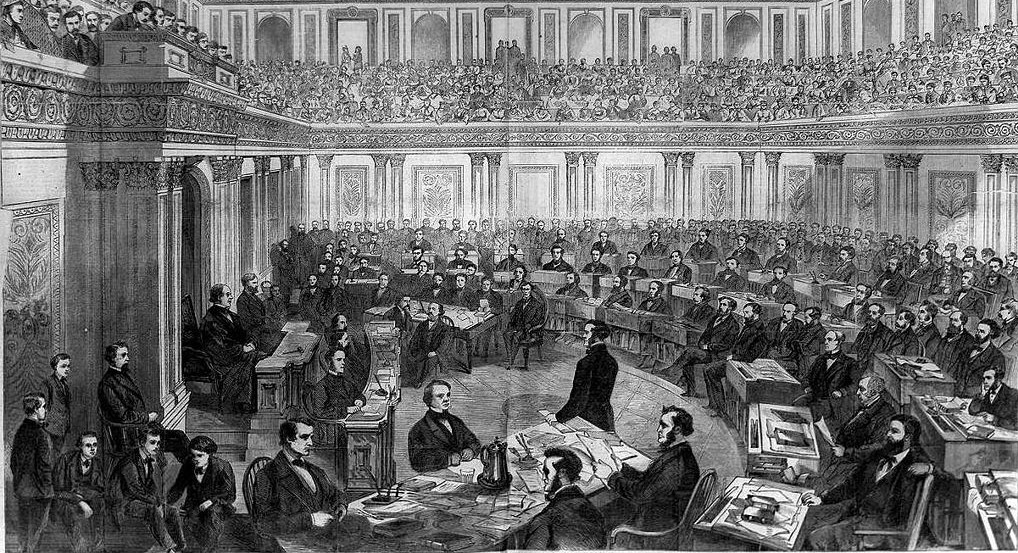

On December 6, 1867, Chairman Boutwell reported the Judiciary Committee's recommendation for impeachment. He listed among numerous allegations of presidential misconduct Johnson's failure to enforce the act calling for the distribution of the abandoned lands to the freedmen, his disregard of the Test Oath Act, and the failure to keep the peace in New Orleans. Calling for impeachment in a speech on the floor of the House, Boutwell said, “... when you consider all these things can there be any doubt as to his purpose, or doubt as to the criminality of his purpose?” His colleagues did have doubts; they defeated the recommendation for impeachment on December 7, 1867, by 57 votes for impeachment, 108 against.

Michael Les Benedict is one recent historian who, like the House Judiciary Committee, takes seriously the compound effect of Johnson's acts in the South. Benedict does not accept the long-standing view that Andrew Johnson's acquittal in the later Senate trial was just reward for a man beleaguered by vindictive radicals. Not unlike Boutwell, Benedict ponders the nature of Johnson's offenses. At one point, he says, “Yet Johnson had broken no law; he had limited himself to his constitutional powers” but in another place he states, “Johnson had already shown his willingness to nullify Congressional legislation” by failing to enforce it.

The consequence of Johnson's actions, he believes, was that by 1868 the “Reconstruction program enacted by Congress lay in utter ruin.” To such incidents as the New Orleans riot, he adds interference with, and removal of, federal officials charged with carrying out congressional programs and stresses as a major abuse of power Johnson's having “appointed provincial governors of vast territories without the advice and consent of the Senate.”

Johnson placed no obstacles in the way of the Judiciary Committee's investigation of the many witnesses and its examination of many executive documents, including letters, telegrams, and memoranda sent to federal officials in the South. The President complied with requests for personal data. For example, William S. Huntington, cashier of the First National Bank of Washington, was allowed to give full information on the President's personal account. Huntington reported that the President “said he had no early objection to have any of his transactions looked into; he had done nothing clandestinely. ...”

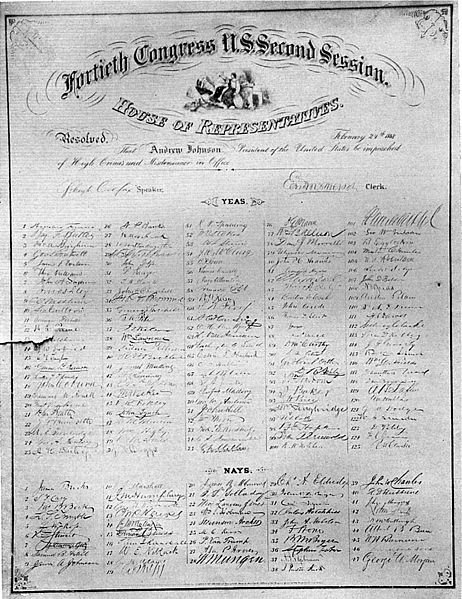

Dropping the effort to establish the President's guilt by a collectivity of abuses, the House of Representatives turned to a specific act of defiance of Congress. It voted impeachment on Johnson's removal of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in violation of the provisions of the Tenure of Office Act. This alleged abuse of power by the President was one for which he took open public responsibility. The impeachment was approved by the House of Representatives on February 24, 1868, by a vote of 126 to 47. The eleven articles of impeachment on which the Senate had to judge Johnson focused on the narrow issue of the removal of Secretary Stanton, and not on the earlier charges of failure to uphold congressional laws, but it should be noted that the removal of Stanton was closely tied to the earlier abuses.

By 1867 Stanton was the only remaining member of the cabinet critical of the President's reactions to congressional Reconstruction. His position with respect to carrying out the program was crucial. The only administrative payroll available for carrying out federal policies in the South was the army's. The Freedmen's Bureau was a part of the War Department. Thus the seemingly narrow issue of the removal of Secretary of War Stanton was not totally a deflection from the congressional concern with the broader matter of Johnson's frustration of its Reconstruction program.

In the eyes of Johnson's opponents, the removal of Stanton was not dissimilar to the removal of Conway from Louisiana in 1865; of Saxton from South Carolina in 1866; of Wager Swayne, who had supported some of the acts favorable to the freedmen while assistant commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau in Alabama in 1867; and of General Philip Sheridan from Louisiana. Chairman Boutwell pointed to such acts as prime examples of the multiplicity of offenses for which Johnson was culpable. In 1868 the House concentrated on only one highly specific issue, the Stanton removal.

Article Ten, which quoted from speeches in which President Johnson defied Congress, and the first section of Article Eleven, which accused Johnson of challenging the authority of Congress to act at all (on the ground that former Confederate states were not represented), alluded to the abuses of power catalogued in the earlier House Judiciary Committee report. The other nine articles and the balance of Article Eleven related explicitly to the Stanton removal. The subject of the trial was the Stanton matter and, more fundamentally, constitutional questions of presidential and congressional authority, rather than misconduct and abuse of power. In May, 1868, the President was acquitted when, for the lack of one vote, the two-thirds majority was not attained.

In areas outside Reconstruction, the Johnson administration underwent the usual congressional scrutiny. In investigations of frauds in the collecting of taxes in the distillery industry and customs in the collector's offices in the various ports, many local officers were found culpable. The 1867 Congressional Investigating Committee found no substantiation for allegations that payments of $5,000 each were offered to Sen James R. Doolittle and David T. Patterson (Johnson's son-in-law), both of whom were to vote for Johnson's acquittal, and to Robert Johnson, the President's son, and that such sums were not received by the three men. Neither Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch nor President Johnson was accused of knowledge of such abuses or of failure to act to prevent them.

The acrimony between Johnson and his congressional opponents was intense. His accusers were not apt to have overlooked any evidence of abuses involving financial corruption, and none of substance was presented. Andrew Johnson generated hatred on ideological issues, but personally he was scrupulously honest.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.