The Senate convened twenty years ago to determine whether President Bill Clinton had committed "high crimes and misdemeanors"

-

Winter 2019

Volume64Issue1

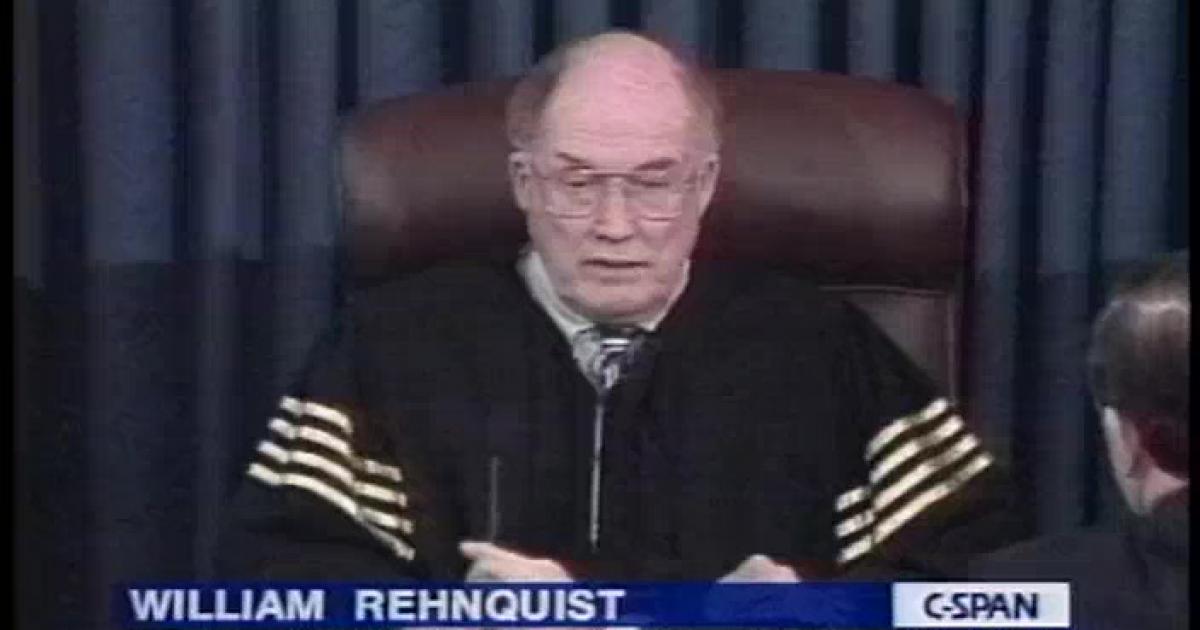

Two decades ago, Americans were treated to a bizarre and dispiriting television spectacle when Chief Justice William Rehnquist convened a special session of the United States Senate. Decked out in his trademark black robes, with four gold-braid stripes sewed into each sleeve—a nod to the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta Iolanthe, which premiered in London in 1882—Rehnquist became only the second chief justice in American history to impanel the Senate as a jury in a presidential impeachment trial.

The question before that body was deceptively simple: Did President William J. Clinton commit high crimes and misdemeanors worthy of his removal from office?

Clinton’s troubles had begun more than five years earlier, when Attorney General Janet Reno appointed a special counsel to investigate improprieties the President might have committed in the 1970s, when he and his wife invested in a land development deal along the Whitewater River in Arkansas. In turning the matter over to a special counsel, Reno faced a double challenge. On one hand, the 1978 statute allowing for the appointment of independent prosecutors had expired, leaving her without formal rules about how to initiate an inquiry. On the other hand, she was a member of Bill Clinton’s cabinet; accordingly, she felt obliged to go the extra mile in removing any appearance of a partisan cover-up. So she tapped Robert Fisk—a former federal prosecutor and a Republican—to investigate the Whitewater affair.

Months later, however, Congress reauthorized the special-prosecutor statute, prompting Chief Justice Rehnquist to name a three-member panel of federal judges to appoint a new independent counsel. Their choice was Kenneth Starr, a former solicitor general in the Bush administration and a fierce political opponent of Clinton. At the time of his appointment as special prosecutor, Starr was serving as a legal adviser to Paula Jones, a former Arkansas state employee who was suing Clinton for civil damages related to an alleged case of sexual harassment dating back to 1991.

Democrats cried foul, arguing that there was nothing “independent” in Kenneth Starr’s record of partisan loathing for Clinton. But Starr remained on the job, and what came to be widely perceived as his public crusade took a heavy toll on the administration. With the President under close scrutiny, Republicans swept off-term elections in November 1994, capturing both houses of Congress for the first time in more than 40 years. Clinton then faced the unenviable position of presiding over a divided government.

If Kenneth Starr proved a thorn in his side, the President nevertheless contributed mightily to his own troubles. Between November 1995 and May 1996—while he was under investigation for possible financial improprieties—Clinton carried on a sexual affair with Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern. Then the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the President didn’t enjoy executive immunity against civil claims, thus allowing Paula Jones, whose legal team still maintained close contact with Starr, to move ahead with her sexual-harassment suit.

Further complicating matters, Lewinsky, who had been transferred to the Department of Defense, began confiding in Linda Tripp, a 48-year-old disgruntled secretary who had also been rotated out of the West Wing and over to the Pentagon. Tripp secretly recorded their conversations, in which Lewinsky disclosed sordid details of her relationship with the President, and handed over copies to Paula Jones’s lawyers. The lawyers in turn subpoenaed Lewinsky, in an attempt to establish that Clinton had exhibited a pattern of initiating sexual encounters with his subordinates.

All the while Kenneth Starr, frustrated by his inability to make headway in the Whitewater probe, sought and received permission to extend the scope of his inquiry. Armed with insider information from Jones’s legal team, he began constructing a shaky case against the President, claiming that Clinton had engaged in a criminal conspiracy to suborn perjury and obstruct justice. In a 445-page report that he submitted to Congress in September 1998, along with 3,000 pages of supporting documents, Starr alleged that, by helping Lewinsky secure a job in New York, the President had encouraged her to offer false testimony in the Paula Jones civil suit. He also charged the President with lying to friends and associates in an effort to encourage them to offer false testimony before a federal grand jury.

Matters came to a head in late 1998, when the House of Representatives passed two articles of impeachment against the President.

House Republicans badly misjudged public opinion. As it became clear that he had all but lied about the Lewinsky affair on national television, Clinton’s personal approval ratings plummeted. Yet even in early 1999, as he faced a trial in the Senate, his job performance numbers remained extremely high—over 70 percent, according to some polls.

By contrast, Kenneth Starr quickly burned through any residual good will he might once have enjoyed. Only 19 percent of Americans approved of the job he was doing, while 43 percent disapproved. In effect, he struck most Americans as a ruthless prig who would go to any lengths to bring down the President. That his office consistently—and illegally—leaked details of the federal grand jury investigation only further contributed to the growing sense that he was a partisan hack.

Ultimately the Senate acquitted Clinton on both counts. The President may have done a great deal to undermine his personal credibility, but most Senators agreed that his trespasses did not warrant his removal from office.

Around the time of Clinton’s impeachment, many commentators drew parallels to 1868, when the House of Representatives impeached—and the Senate acquitted—President Andrew Johnson. The legal writer Jeffrey Toobin, in The New Yorker, called the events of 1868 a constitutional “fiasco” and “the low point in impeachment history.”

In fact the comparison was a poor one. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Andrew Johnson violated federal laws by appointing former Confederate officials to state and local offices. He also refused to carry out his responsibilities under the 1867 Military Reconstruction Act and called for the lynching of a United States congressman. Johnson’s offenses, in other words, were highly impeachable and may very well have warranted conviction. Certainly many would have agreed they were graver than Clinton’s affair with a White House intern and his subsequent efforts to conceal that affair.

The lasting tragedy of the Clinton trial, and of the popular comparison to 1868, may be that many Americans now regard the impeachment process with a skeptical eye. Because of the popular perception that Kenneth Starr and his Republican allies abused their authority, impeachment seems just another blunt tool in the never-ending, mind-numbing cycle of partisan warfare.