Four hundred years ago this year, two momentous events happened in Britain’s fledgling colony in Virginia: the New World’s first democratic assembly convened, and an English privateer brought kidnapped Africans to sell as slaves. Such were the conflicted origins of modern America.

-

Winter 2019

Volume64Issue1

Historian James Horn, a frequent contributor to American Heritage, is President of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation. Portions of this essay appeared in his recent book, 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy (Basic Books).

Along the banks of the James River, Virginia, during an oppressively hot spell in the middle of summer 1619, two events occurred within a few weeks of each other that would profoundly shape the course of history. Convened with little fanfare or formality, the first gathering of a representative governing body anywhere in the Americas, the General Assembly, met from July 30 to August 4 in the choir of the newly built church at Jamestown. Following instructions from the Virginia Company of London, the colony’s financial backers, the meeting’s principal purpose was to introduce “just Laws for the happy guiding and governing of the people.” The assembly sat as a single body and was made up of the governor, Sir George Yeardley, his four councilors, and twenty-two burgesses chosen by the free, white, male inhabitants of every town, corporation, and large plantation throughout the colony.

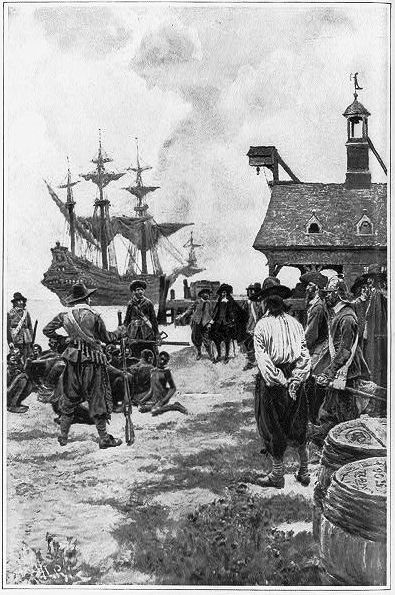

A few weeks later, a battered English privateer, the White Lion, entered the Chesapeake Bay and anchored off Point Comfort, a small but thriving maritime community at the mouth of the James River that was often a first port of call for oceangoing ships. While roving in the Caribbean, the ship, together with its companion, the Treasurer, had been involved in a fierce battle with a Portuguese slaver bound for Veracruz. Victorious, the two privateers pillaged the Portuguese vessel and sailed away northward carrying dozens of enslaved Africans.

Running short of water and provisions, they headed for the nearest English haven, Virginia, where a couple of weeks later the prominent planter John Rolfe reported that the White Lion had “brought not anything but 20 and odd Negroes,” who were “bought” (my italics) for food supplies. The Treasurer entered the James River a few days later but opted to leave quickly, possibly after clandestinely selling some of the African captives on board. Forcibly transported from West Central Africa (modern-day Angola), they were the first Africans to arrive in mainland English America.

No one in Virginia in 1619 or in the years following could have possibly grasped the importance of what had occurred. Settlers understood that the assembly allowed them to have a hand in governing themselves, but they were motivated more by opportunities to approve laws sent by the Virginia Company from London and to propose their own legislation rather than by abstract concepts of self-government or subjects’ rights and liberties.

Equally, no documented discussion took place in the colony about the morality of owning and enslaving Africans. Deliberations in future general assemblies at Jamestown, as mirrored later in colonial legislatures across English America, focused far more on policing measures against Africans and protecting the rights of masters than on the rights of the enslaved or ethical considerations. Slavery, African and Indian, together with a broad spectrum of white non-freedom—apprenticeships, convict labor, and serfdom—were simply taken for granted in the emerging Atlantic world of the time and elicited little comment.

Yet the coincidence of the meeting of the first representative government and arrival of the first enslaved Africans in the summer of 1619 was portentous. Historians have argued that the rise of liberty and equality in America, America's democratic experiment, was shadowed from its beginning by its dark obverse: slavery and racism. Slavery in the midst of freedom, Edmund Morgan writes, was the central paradox of the birth of America. The rapid expansion of opportunities for Europeans was made possible only by the enslavement and exploitation of African and Indian peoples. Non-Europeans were consigned to a permanent underclass excluded from the benefits of white society, while Europeans profited enormously from the fruits of the labors of those they oppressed.

See also “Why Jamestown Matters” by James Horn

Arguably, then, 1619 marks the inception of the most important political development in American history, the rise of democracy, and the emergence of what would in time become one of the nation's greatest challenges: the corrosive legacy of racial stereotypes that continues to afflict our society today.

Despite the significance of 1619 and surrounding years, this period is almost entirely unknown to the public. Insofar as any attention has been given to early Virginia, the dominant narrative portrays Jamestown as an unqualified disaster, little more than a “dismal and fraught” precursor of the successful godly settlements in New England where, so it goes, America’s story really begins. For the nation at large, Plymouth in 1620 or the founding of the Puritan colony of Massachusetts a decade later exerts a far greater influence on our collective historical memory than the founding of Virginia in 1607 or the events of 1619.

This is especially perplexing considering that what took place in early Jamestown had far-reaching implications for all English colonies that followed in Virginia’s wake, as well as eventually on the creation of the United States itself.

Owing to numerous setbacks, the Virginia colony struggled in its early years, leading the Company to introduce wholesale reforms in an effort to save it from collapse. Still largely an experimental period in England’s empire-building trajectory, the import of 1619 derives from the consequential philosophical and political assumptions that guided the reforms, though they in turn led to unforeseen and tragic outcomes that ultimately brought an end to the project. Instigated by the highly respected parliamentarian and leader of the Virginia Company, Sir Edwin Sandys (pronounced Sands), propertied white males in the colony were granted remarkable political freedoms as well as opportunities to share in the running of their own affairs. In addition, plans were put in place to promote a harmonious society where diverse peoples and religious groups would live together side by side in peace to their mutual benefit.

Because so many influential parliamentary leaders were involved with the Company, proposals for Virginia were informed by the wide-ranging political debates taking place simultaneously at James I’s court and in Parliament, which linked developments in the fledgling colony to domestic and international issues of momentous consequence. By 1619, the Virginia Company was recognized by many in high political circles as a laboratory for some of the most advanced constitutional thinking of the age.

Company leaders grounded their efforts to establish a godly and equitable society in the philosophical theory of the commonwealth. The term commonwealth, or the “common weal,” emerged in Europe in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and brought together a variety of political and economic precepts that highlighted the common good of the people.

Particular emphasis was given to the importance of wise and noble rulers and mixed government — a salutary balance of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy — as well as Christian morality; prosperity, and social well-being. Linked to Renaissance humanist ideas, statesmen and intellectuals believed that the application of rational approaches to government and social and economic organization would encourage the improvement of societies and the human condition. Where better to test these ideals than the New World?

In Virginia, commonwealth theory guided the leadership’s approach to every facet of the emerging colony, including government, the rule of law, protections for private property, the organization of the local economy, and relations with the Powhatans, the Indian peoples whose territories surrounded English settlements. The great reforms introduced in 1619, therefore, were all-encompassing, not directed simply toward the creation of a legislative body.’

Within a few years, Sandys’s dream of a model American commonwealth had been shattered. A series of disasters, including a massive attack by Powhatan warriors that killed hundreds of settlers, political intrigue involving the king and his ministers, and deep divisions among Company leaders in London, ultimately led to the Company’s collapse. The colony survived, however, which attested to the commercial success of preceding years, but after 1625 in the absence of Company rule, a quite different society emerged from that promoted by Sandys.

A commonwealth was founded on the well-being of the people as a whole, not the few; this was a fundamental principle emphasized by classical philosophers of Greece and Rome as well as by leading statesmen of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Sandys and other Company officers adopted initiatives they believed would stimulate prosperity for broad sections of society and sought to prevent wealthy planters from gaining excessive influence in the colony.

These measures involved limitations on the powers of the governor and his councilors, an emphasis on the rule of law, and the founding of the General Assembly, which was created specifically to represent the majority of settlers, not only the rich. The Company’s wholehearted support of reformed Anglicanism and Christian morality encouraged neighborly support and care for others as well as individual piety and moral discipline.

Following the Company’s demise, efforts and legislation put in place to encourage the common good and a wide-spread equality of interests were quickly abandoned. Even before the collapse of the Company, conspicuous disparities in wealth had begun to surface. Soon after tobacco became established as the colony’s principal commodity, a boom in the price of tobacco leaf on the London market enabled a small group of planters and government officials to become extremely rich by steadily amassing land and laborers. Affer the Powhatan attack of 1622 that nearly destroyed the colony, racial stereotypes demonizing the Indians were quickly adopted by settlers to justify the slaughter of Indian peoples and appropriation of their territory. Huge areas of prime agricultural lands were taken up by settlers, creating the first English land rush in America.

Some Powhatan captives were enslaved and joined Africans in bondage; other Indian peoples moved out of the region beyond the reach of settlers.

The Company’s commonwealth project was also condemned by critics for being dangerously egalitarian. Captain John Bargrave, a prominent merchant-planter, wrote forcefully that the “mouth of equal liberty must needs be stopped,” denouncing what he saw as the overt populist tendencies among Company leaders, including Sandys. “Extreme liberty,” he warned, was more perilous to the political and social order than “extreme tyranny.” Political leadership, lauded among the responsible, propertied classes, was not deemed suitable for the poor and landless who comprised the vast majority of people in early modern society.

It was axiomatic among the upper classes that poor people’s lack of independence, property, and education disqualified them from prominent roles in society. In Virginia, where poor workers made up a far higher percentage of the total population than in England, political power rapidly became concentrated in the hands of small groups of wealthy planters who, largely autonomous in their own localities and insulated from close oversight by English government officials three and a half thousand miles away, became accustomed to a freedom of action unthinkable at home.

While Virginia and the American colonies were attractive to countless middle-class British immigrants and other Europeans during the seventeenth century precisely because of the perceived benefits of political and economic liberty, those very freedoms permitted the wholesale and largely unchecked exploitation of lower-class whites, Africans, and Indians. For most poor English settlers, crossing the Atlantic to Virginia or other colonies was a gamble of heroic proportions whereby a fortunate few might succeed in vastly improving their material condition through luck, hard work, and timing, but the great majority did not.

For the mass of Indian and African peoples, of course, even the faintest glimmer of hope of personal improvement was denied them. Slavery and inequality thus arose as synchronic opposites of liberty and opportunity; products of the same political and economic forces.

At the dawn of the British Empire, it was unclear how colonies in North America would evolve. Successive Spanish ambassadors in London feared they would be little more than “pirate nests,” or develop as fishing stations and trading posts such as those founded in Newfoundland by different nations or along the Hudson River by the Dutch. Or would they become stable and prosperous British settlements that would eventually spread across the entire northern continent?

Virginia was the first of England’s settlements in America to persist and ultimately flourish. The great reforms of 1619 that took place at Jamestown had an enduring influence on the development of Virginia and British America and heralded the opening of an extended Anglo-American examination of sovereignty, individual rights, liberty, and constitutionalism that would influence all Britain’s colonies.

Representative government spread outward across the continent, beginning the vital democratic experiment that has characterized American society down to our own times. Concurrently, Virginia’s early adoption of slavery and dispossession of Indian peoples reflected and reinforced racial attitudes that began the highly discriminatory processes that have stigmatized society ever since. Such were the conflicted origins of modern America.

© Copyright 2018 by James Horn. Portions of this essay appeared in 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy, published by Basic Books, New York.