What the future president learned during a coast-to-coast military motor expedition would later transform America.

-

July/August 2020

Volume65Issue4

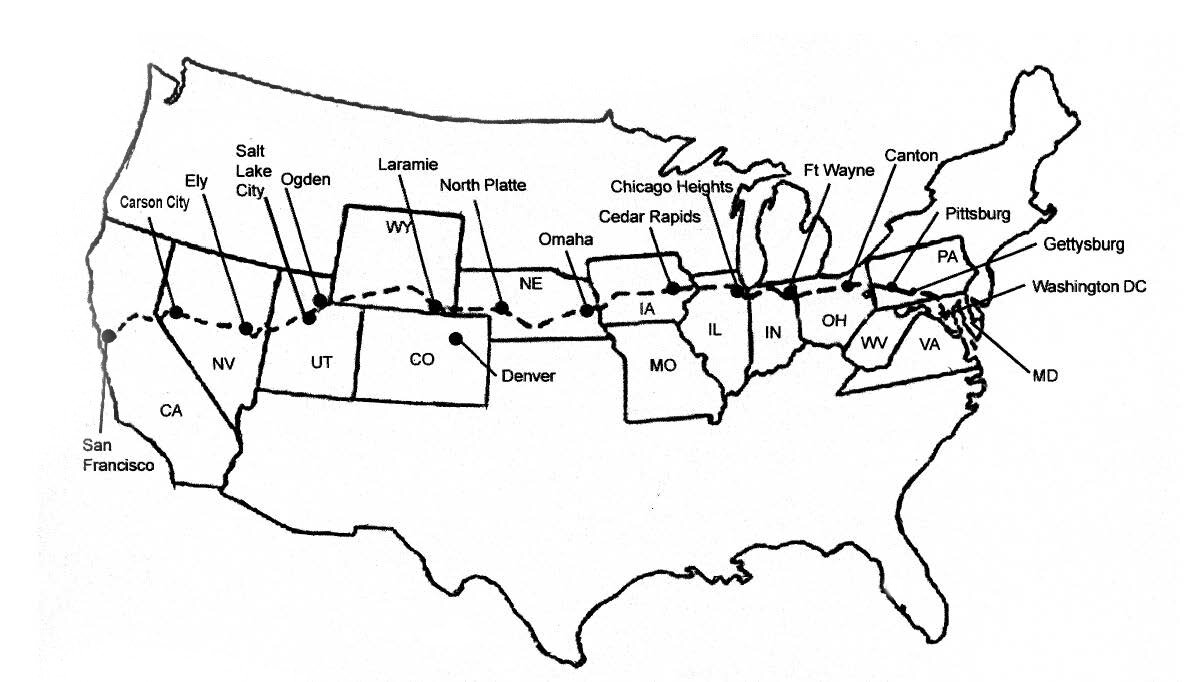

July 7, 1919 — Three days after the Fourth of July, at the Ellipse fronting the White House, a convoy of 81 vehicles lined up, facing west. Flags flew. Bands played. The Secretary of War hailed “the beginning of a new era.” Finally, at 11:15 a.m., the convoy was ready for its perilous, uncharted journey. The destination — San Francisco.

For the previous half century, trains traveled coast-to-coast in just a week. But by truck, the 3,200-mile slog was expected to take. . . two months. With a roar of engines, cheers from the crowd, and smiles from the 250 volunteer adventurers, the Transcontinental Motor Convoy set out across America.

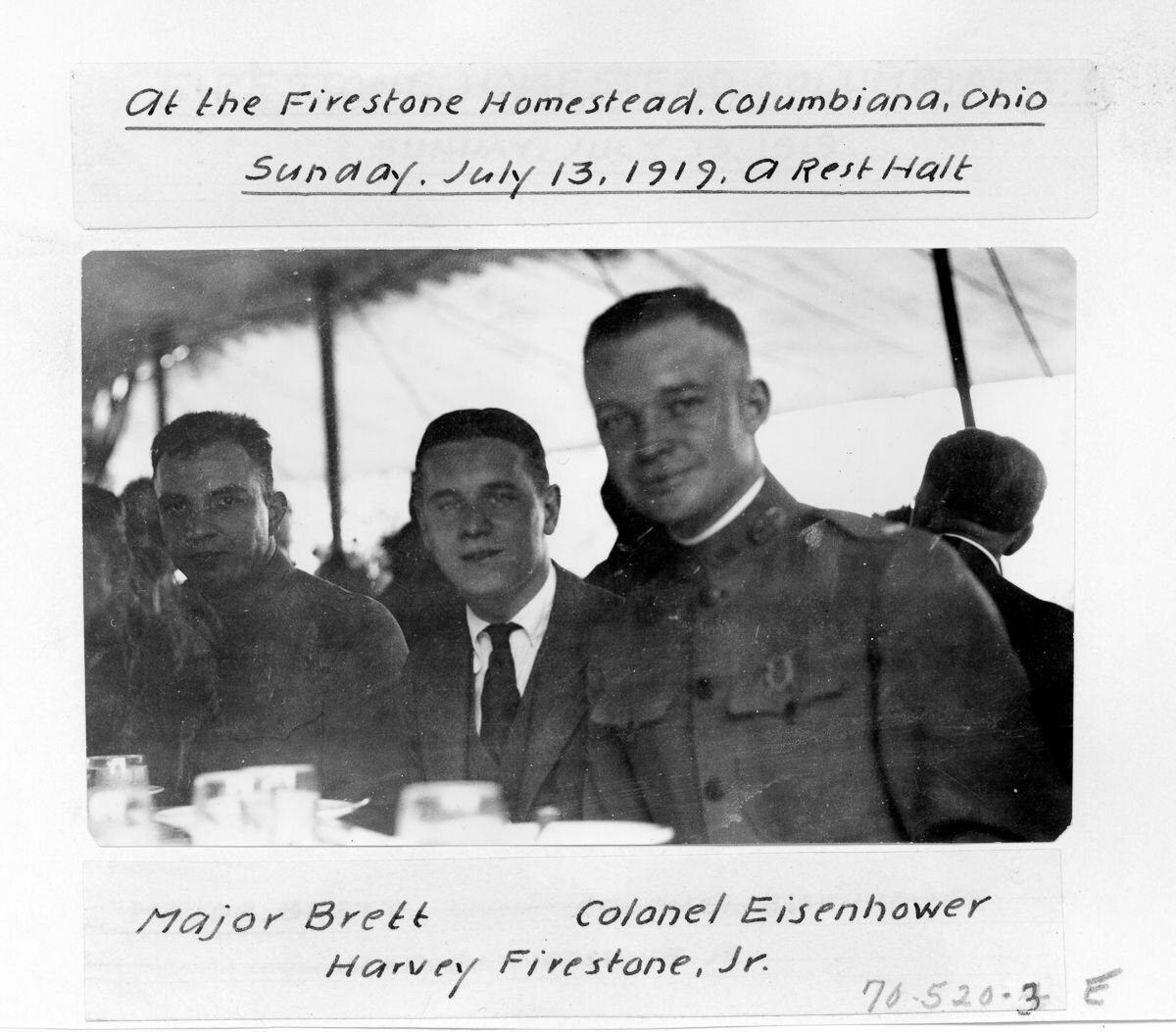

This wild journey would be a historical footnote but for one army officer along for the ride. His name was Eisenhower.

Ike, as everyone called him, was 28. The previous autumn, he had just missed World War I, the armistice coming a week before he was to ship out for France. Now he saw himself “in the years ahead putting on weight in a meaningless chair-bound assignment, shuffling papers and filling out forms.” So when the army sent its motor pool coast-to-coast, Ike volunteered, “partly for a lark, and partly to learn.” What he learned would later transform modern America.

By 1919, cars were common on American roads, but those roads turned mean at city limits. A patchwork of “seedling miles” had been paved by a Good Roads Movement, but the rest of America was hard travelin’. Mile after mile was unpaved, riven with mud and potholes, trenches and debris.

Crossing this wilderness, throughout that summer a century ago, came the convoy. Along with trucks, the two-mile parade included Packard cars, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, and support vehicles — mobile kitchens, a blacksmith van for forging engine parts, truck full of tires, water, and gasoline, and the most crucial vehicle, a tank to tow any vehicle out of a ditch.

The first dozen days, tracing the 19th century Lincoln Highway, were routine. Sixty, seventy miles, with smooth gravel through Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. But at the Illinois line, the trouble began.

For the rest of the journey, each day’s log reads like an auto parts catalog. Broken crankshafts. Worn out magnetos. Blown gaskets, leaky radiators, “carburetor trouble. . .”

Each night told a different story. By late July, the convoy was national news. In small towns, Ike and his colleagues were paraded down Main Streets, fed chicken dinners, hailed as heroes. Then came the dancing — in tents, grange halls, or beneath open skies on the Plains.

On the convoy went, stopping again and again for breakdowns. A motorcycle “turned turtle in a ditch.” Bridges up ahead! Some “rickety,” others “dangerous” or “doubtful.” “Deep ruts.” “Chuck holes.” Broken axles and sheared bolts. But what astonished Ike the most was the men.

“We were a traveling troupe of clowns,” he later wrote. Some clownish behavior was innocent fun, as when Ike and a friend gave Indian war whoops that had a camp guard shooting into the night. But Ike was appalled by ragtag farmboys and returned vets, out for reckless adventure.

Rain made roads sloppy, sending rookie drivers careening along culverts. One day, 25 trucks slid off the road. Another day, a downhill driver downshifted to slow his truck. But instead of third to second, he threw it in reverse. Tore the drive shaft right out from under him.

Nebraska sand clogged engines and ground gears. Wyoming was “the worst,” Ike remembered. Roads had to be built from scratch, bridges repaired before crossing. From Utah onward, the road was “one succession of dust, ruts, pits, and holes.” Finally, California’s Sierra Nevadas.

On old logging or mining roads, the convoy climbed and climbed. The ascent, 14 miles, took six hours. At last came the summit, 7030 feet. It was all downhill to the Pacific.

Rolling into the Sacramento Valley, on “concrete roads lined with palm trees” the men met people tossing them fruits and vegetables. More dances, more banquets. And on the last morning, fresh uniforms.

On September 6, five days behind schedule, some 70 vehicles pulled up at the ferry in Oakland. By afternoon they had driven past crowds lining Market Street. Arriving at the Presidio army base overlooking the bridgeless Golden Gate, the men planted another stone marker to bookend the Zero Milestone they’d installed at the Ellipse near the White House.

Coast-to-coast in 62 days. 230 breakdowns. 25 men left behind sick. A dozen vehicles abandoned. Three million Americans waving, cheering. And one future president.

Thirty-seven summers later, President Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Bill, a stroke of the pen approving 41,000 miles of smooth road. Ike, remembering his trip “through darkest America with truck and tank,” knew the interstate would be more than another public works project. It would change America.

“The old convoy had started me thinking about good two-lane highways,” Eisenhower said. Having been there, and having seen Germany’s impressive autobahn, the traveler turned president saw “the wisdom of broader ribbons across our land.”