Newly released personal papers and transcripts of closed-door hearings reveal both the depth of the senator’s conniving and his surprising charm.

-

July/August 2020

Volume65Issue4

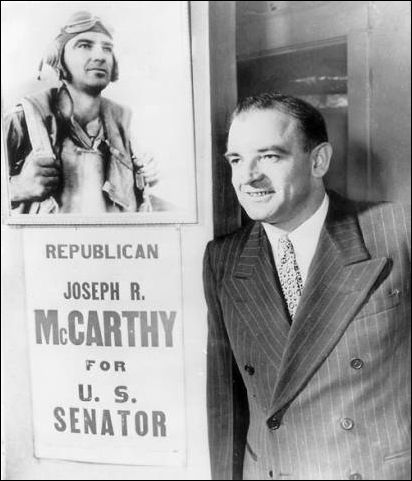

Editor's Note: Historian Larry Tye has just written a definitive biography of the controversial Red-hunting Senator, Joe McCarthy, Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy. We asked him to give us a preview of some of the fascinating material he found in previously inaccessible files.

It would be easy to assume there is nothing new to say about Senator Joe McCarthy more than 60 years after his death, and with a library of books documenting his life and movement. Easy, but untrue.

That’s because, for the first time, we have access to the stash of Joe’s personal and professional papers that his widow donated in 1961 to his alma mater, Marquette University, and that were made available exclusively to this author. Now, finally, we can read his unscripted writings and correspondence, military records and wartime medical charts, love letters, financial files, and even his academic transcripts.

And there is more. Only a third of the hearings where McCarthy badgered witnesses in his search for fantastical conspiracies happened in public session. Evidence of the rest, filling almost 9,000 pages of transcripts, was kept under lock and key for half a century.

These seminal documents give us a new and nuanced appreciation of “Low Blow” Joe, one of the most reviled figures in U.S. history. It’s not often that a man’s name becomes an “ism” – in this case a synonym for reckless accusation, guilt by association, fear-mongering, and political double-dealing. In the early 1950s, the senator from Wisconsin promised America a holy war against a Communist “conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man.”

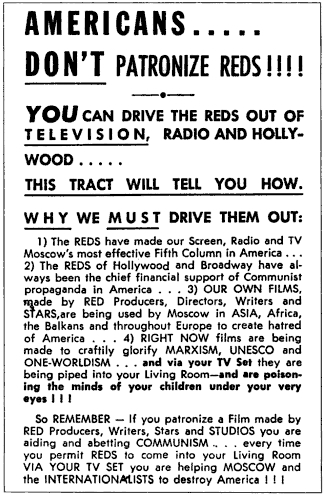

While the conspiracy and infamy claims were a stretch, the body count was measurable: a TV broadcaster, a government engineer, current and former U.S. senators, and incalculable others who committed suicide to escape McCarthy and his warriors; hundreds more whose careers and reputations he crushed; and the hundreds of thousands he browbeat into a tongue-tied silence. His targets all learned the futility of taking on a tyrant who recognized no restraints and would do anything – anything – to win.

“To those of you who say that you do not like the rough tactics – any farm boy can tell you that there is no dainty way of clubbing the fangs off a rattler or killing a skunk . . . It has been a bare-knuckle job. It will continue as such,” the farm-bred soldier turned senator delighted in telling audiences about his hunt for pinkos and Reds. “I am afraid I will have to blame some of the roughness in fighting the enemy to my training in the Marine Corps. We weren’t taught to wear lace panties and fight with lace hankies.”

But Joe McCarthy’s story is more than the biography of a single bully. A uniquely American strain of demagoguery has pulsed through the nation’s veins from its founding days. Although Senator McCarthy’s drastic tactics and ethical indifference make him an extraordinary case, he was hardly an original. He owed much to a lineup of zealots and dodgers who preceded him – from Huey “The Kingfish” Long to Boston’s “Rascal King” mayor James Michael Curley and Michigan’s Jew-baiting radio preacher Father Charles Coughlin – and he in turn became the exemplar for nearly all the bullies who followed. Alabama governor George Wallace, Nation of Islam minister Louis Farrakhan, and Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke tapped the McCarthy model, appealing to their countrymen’s simmering fears of imagined subversions even as they tried to escape the label of McCarthyism. All had big plans and glorified visions in which they played the crowning roles.

Now that we have access to the full sweep of the records on Joe McCarthy’s transgressions, we can see that his rise and reign also go a long way toward explaining the bipartisan queue of fanatics and hate-peddlers who continue to tap into America’s deepest insecurities. In lieu of solutions, demagogues point fingers. Attacked, they aim a wrecking ball at their assailants. When one charge against a manufactured enemy is exposed as hollow, they lob a fresh bombshell. McCarthy was neither the first, nor the last. But he was the archetype, and his playbook set the template.

At the time when McCarthy drafted his poisonous script, few people knew the Wisconsin native’s full story. America got its best look at the single-minded senator in his public and prodigiously publicized hearings, when he targeted alleged Soviet infiltration of the Foreign Service, the Voice of America, and, in a step too far, the mighty U.S. military. “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?” the Army’s special counsel famously asked him on live television in the spring of 1954, echoing what much of the nation was thinking by then. Americans would have been asking a lot sooner, and reached a quicker tipping point, if they had witnessed the secret hearings McCarthy was holding.

Those records, recently unveiled by the Senate historian and never before closely examined, reveal in disturbing detail that when the subcommittee doors slammed shut, Chairman McCarthy came unhinged in a way unimaginable to most Americans. He ceased even pretending to care about the rights of the accused, whom he summarily declared guilty. He held one-man hearings, in violation of long-standing Senate tradition. When he was absent, his poorly trained, sophomoric staffers leapt in to badger witnesses on his behalf.

The executive sessions were an unsanitized, easy-to-understand blueprint for McCarthyism. As famously madcap as the heretical senator appeared in his public hearings, comparing the open and closed sessions makes plain that the TV cameras and public galleries acted as a restraint rather than the license to grandstand that they are for many politicians. Here in private, finally, we get the real Joe – penetrating and quick-witted at moments, but more often irascible, irresponsible, and irrepressible.

Nowhere was that clearer than in his efforts to unearth embarrassing revelations about events in a witness’s youth, or even before she or he was born. The political beliefs of colleagues, neighbors, and family members all were fair game. Those who swore they had never joined the Communist party or engaged in espionage were held accountable for long-forgotten petitions they signed or for joining organizations the attorney general would later cite as Communist fronts. The point was to mark them as guilty by early indiscretion. Guilty by friendships. Or guilty by suspicious parentage. Whatever the reason, the guilt was presumed, whereas innocence had to be proven.

In the process he redefined the very notion of what a witness was. Most who were called by Joe weren’t there to offer evidence that could shed light on a particular question being investigated, the way they would have been in a courtroom or before most congressional committees. More often they themselves were the subject of Joe’s probe. His staff or his legions of leakers had given him the names. He summoned them because he considered them guilty and sought to expose their wrongdoing, or the misdeeds of others. To label them witnesses sugar-coated the reality of their presence before his tribunal, as many who were blameless as well as naive quickly learned.

A last thing stood out about the hush-hush hearings: their chairman seemed to get ornerier in the afternoon hours, if the midday break had been long enough for him to enjoy the martini-lubricated lunch that was standard for many lawmakers in that era.

What about his claims to have lists of Communists lurking at the State Department and throughout the government? It is true that he ferreted out a handful of leftists, but most were indictable more for youthful idealism and political naïveté than the sedition and treason of which they were accused. He searched in vain for a big fish – his own Alger Hiss or Julius Rosenberg – and targeted fellow lawmakers who dared challenge his shakedowns.

If that is the darker-than-we-knew side of Joseph Raymond McCarthy, there is also an untold tale of the beguiling charm with which he seduced the Badger State and much of America. Snippets of the private Joe – the relentless yet riveting sycophant, incongruously generous to those he had just publicly upbraided – have filtered out over the decades, but these generally came from unreliable sources bent on shielding or savaging the senator.

These new documents reveal a figure far more layered and counterintuitive than the two-dimensional demagogue enshrined in history. Just three years before he launched his all-out crusade against Russian-style communism, McCarthy was taking courses in the Russian language and assuring his instructors they were playing a role “in the furtherance of peace and understanding among the people of the world.” Later, when his Red-baiting was going full-steam and his favorite target was Harvard University – McCarthyites called it “Kremlin on the Charles” – Joe and his wife Jean were troubled by the beating that Harvard physicist Norman Ramsey was taking on the Sunday morning TV show “Meet the Press,” as reporters goaded the professor into defending the university against Joe’s brickbats.

As soon as the show was over, the McCarthys invited Ramsey to a dinner party; he came and stayed for three-and-a-half hours while McCarthy feted him, charmed him, and offered him a job that he declined. “I’m not sure that we convinced him,” Jean McCarthy recalled of their evening with the scientist, who three decades later won a Nobel Prize in Physics. “But I’m sure he left agreeing that Joe doesn’t have horns.” Ramsey himself volunteered a different takeaway: “At that time there was some speculation that McCarthy might become president or even a dictator. After our evening together I concluded this was no threat from McCarthy alone but might be with him and his wife together.”

Even as I was poring through reminiscences like those and all the other collections – along with everything ever written on Joe in books, newspapers, magazines, and yellowing government files – I was racing to reach aging McCarthy friends and colleagues, as well as his enablers and casualties. They, together with their survivors, helped me unwind his tangle of contradictions.

Months before Leon Kamin died, the 89-year-old psychology professor explained that being targeted by McCarthy “left me unemployable in the United States.” Reed Harris, a Voice of America executive whom McCarthy denounced for his campus activism and leftist politics two decades before, wrote in a journal he left to his children that his days testifying before the Wisconsin senator were “the toughest and saddest week of my life, but in a way it also was the finest. For I was able to stand up to McCarthy.” And Bronson La Follette told me that his father, former Senator Robert “Young Bob” La Follette, “committed suicide instead of being called before McCarthy’s committee . . . he was very, very agitated.”

Yet Ethel Kennedy, who got to know the Wisconsinite after he gave her husband Robert his first real job, saw a very different side of the senator. The public may have thought McCarthy a monster, but he actually “was just plain fun,” she told me. “He didn’t rant and roar, he was a normal guy.” Sometimes she and Bobby would visit Joe at his Capitol Hill apartment, bringing along their toddler Kathleen. Joe “just wanted to hold her. We’d be talking and then he’d say something to her,” remembers Ethel. “I have had that kind of bond with somebody else’s baby and so I understand that it can happen. It’s like falling in love.”

Examining the fresh evidence of McCarthy’s official excesses, and his behind-the-scenes humanity, makes him more authentic, if also more confounding. Today, every schoolchild in America is introduced to Joe McCarthy, but generally as a caricature, and their parents and grandparents recall the senator mainly with catch phrases like witch hunter or with a single word: evil.

The newly disclosed records let us shave away the myths and understand how the junior senator from Grand Chute rose to become powerful enough to not just intimidate Dwight Eisenhower, our most popular postwar president, but to provoke senators and others to take their own lives. Pulling open the curtain, Senator McCarthy is revealed as neither the Genghis Kahn his enemies depicted, nor the Richard the Lionheart rendered by friends. Somewhere between that saint and sinner lies the real man. He was in fact more insecure than we imagined, more undone by his boozing, more embracing of friends and avenging of foes, and more sinister.

These documents and testimony tell us one more thing that is unsettling, at least to McCarthy’s most zealous foes: they borrowed too many of his techniques, too eagerly accepting as truth things they couldn’t have known or that they simply got wrong. The gay-bashing senator was not, as rumor had it, himself gay, nor did he skim from his patrons to make himself rich. And despite repeated claims that he never exposed a single Communist in the government, he did — although nearly all were small-time union organizers or low-level bureaucrats and there weren’t nearly as many as he boasted. Most twenty-four carat spies had slipped away long before Joe joined the hunt.

Some call it proper punishment that McCarthy-the-mud-slinger fell victim to his own methods of smear. I find it ironic, and sad, that this senator’s inquisitions first muzzled America’s political left, then, once he and his “ism” had themselves been blackballed, undercut legitimate questions about security and loyalty. That McCarthy crippled anti-Communism at least as much as he did Communism was the singular thing that both Communists and anti-Communists accepted as fact.

Although shameless opportunism may have inspired McCarthy’s anti-Communist jihad, by the end he had willed himself into becoming a true believer in the cause and even cast himself as its Messiah. He didn’t invent the dread of an enemy within that permeated the United States during its drawn-out face-off with the Soviet empire, but he did channel those suspicions and phobias more skillfully than any of his fellow crusaders. In the process, he shattered many Americans’ faith in their government, trust in their neighbors, and willingness to speak up. While his reign of repression lasted barely five years, that was longer than any other demagogue held our attention, and at the height of his power fully half of America was cheering him on.

Before this current era of our riven politics, even a groundbreaking biography of Senator McCarthy might have seemed like a chapter of American history too painful to revisit, one with little relevance to a republic that had outgrown his appeals to xenophobia and anti-establishmentarianism. An autocratically inclined Russia might unite behind the ironfisted Vladimir Putin, and an Italy that had lined up behind flag-waving Benito Mussolini could be lured in again by the anti-globalist Five Star Movement, but surely this would never happen in the judicious, eternally fair-minded United States of America. One need only read the daily headlines, however, to be reminded that this is the story of today and of us.

As gut-wrenching as their tales are, McCarthy and his fellow firebrands offer a heartening message at a moment when we are desperate for one: every one of those autocrats — James Michael Curley and George Wallace, “Radio Priest” Charles Coughlin and “Low Blow” Joe McCarthy — fell even faster than they rose, once America saw through them and reclaimed its better self. Given the rope, most demagogues eventually hang themselves.