The city embodies the American spirit: freedom, democracy, innovation, arts, and a love of knowledge.

-

Spring 2019

Volume64Issue2

Whether you’re a serious historian or you just enjoy learning about the past, Philadelphia has a lot to offer. The first UNESCO World Heritage City in the United States, it has been known variously as the “City of Brotherly Love,” the “Workshop of the World,” the “Cradle of Liberty,” and the “City of Firsts,” among several terms.

Philadelphia has reflected and represented much of the promise and progress of “America” as an idea and a great experiment. Whether in proclaiming freedom and creating new governments, inventing many technological and scientific improvements from bifocals to computers, discovering new medicines, initiating social reforms, and trying different kinds of community living, Philadelphia is like America itself -- a constant work in progress.

Philadelphia’s rich variety of architecture, arts, material culture, visual and verbal documents, and public spaces attest to that ongoing work, past and present. As such, walking about Philadelphia, especially the Old City and Center City areas, will reveal much about American history and culture and suggest what America stands for today.

Philadelphia was a planned city as part of William Penn’s “Holy Experiment,” and throughout its history has remained a place of “experiment” in all manner of fields, from science and technology to social engineering. This was so in laying out the city and trying to govern it. Penn sought order in the grid pattern he mapped out for the city, but people’s interests subverted his design from the beginning as they crowded along the water for access to goods and information.

See "The Ordeal of William Penn" by Francis Biddle in the April 1964 American Heritage

Still, even as Philadelphia physically spread out over time, thanks to such factors as improved transportation and cheap housing (the rowhouse being a Philadelphia hallmark), it retained the basic grid design. To see that design and the city’s expanse, go to City Hall, itself a statement on civic authority, and take the elevator to the viewing station in the tower.

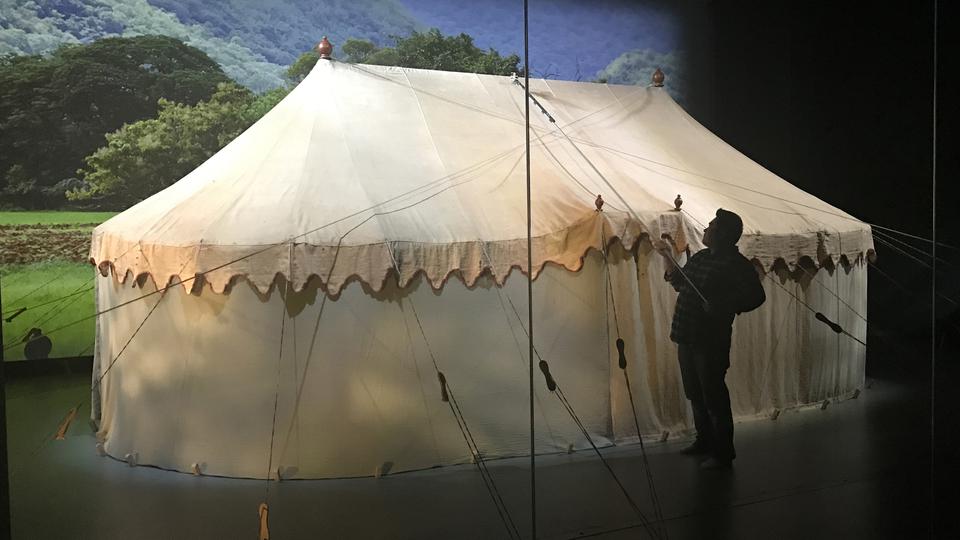

Philadelphia, of course, was the font of American independence, and buildings from the Revolutionary era are now patriotic shrines. For the Revolution, start at the recently opened Museum of the American Revolution on Chestnut Street. Its superb collection (including Gen. Washington's original field tent), exhibitions and theaters engage visitors in the history and continuing relevance of the American Revolution.

From the Museum of the American Revolution, it's a quick walk to Carpenter’s Hall, at 320 Chestnut Street, which was a staging area for anti-British protests and then the meeting place for the First Continental Congress in 1774.

The Congress returned to Philadelphia in 1775. Meeting in the Pennsylvania Assembly building, later named Independence Hall, delegates to the Continental Congress raised a Continental Army, adopted the Declaration of Independence, and signed the Articles of Confederation. In 1787, delegates from twelve states met in Independence Hall, and admittedly in local taverns such as the now reconstructed City Tavern at 138 S. 2nd Street, and drafted the Constitution of the United States. From 1790 to 1800, when Philadelphia was the new nation’s capital, Congress met at Independence Hall to get the new experiment in representative government working.

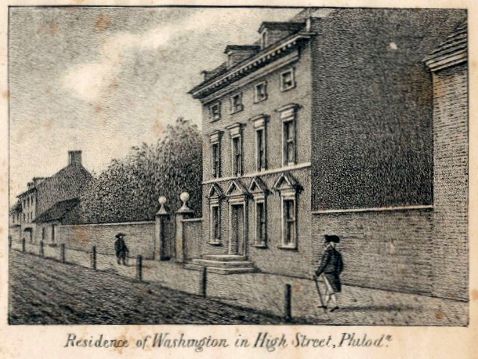

The fundamental paradoxes of Americans’ quest for liberty while sustaining slavery are represented at the President’s House at 6th and Market Streets, where Presidents George Washington and John Adams conducted public business and managed their private interests. The Liberty Bell Pavilion there houses the Liberty Bell and includes an exhibit showing the bell’s emergence as a national symbol, claimed by abolitionists in the 19th century and by other Americans thereafter, though with varying readings of what “liberty” has meant and now means.

For exhibits and programs on the development and interpretations of the Constitution over time to our day, visit the National Constitution Center nearby on the mall at 5th and Arch Streets. The Center was created by the Constitution Heritage Act signed by President Reagan in 1988. The 160,000 sq ft museum opened in 2003 and provides visitors with a variety of experiences including a

The creation of a new nation required physical demonstrations of what it represented and what it intended to be. Visitors can still see buildings in the Old City area that attest to the new nation’s effort to claim a republican lineage and assert a stability, in stone, necessary to gain confidence and support from the people.

Important examples are the First Bank of the United States (on 3rd Street between Chestnut and Market Streets) and the Second Bank of the United States building (on Chestnut Street between 3rd and 4th Streets) with their columned facades suggest ties to ancient Greece and Rome. Alexander Hamilton led the effort to have Congress charter the First Bank in 1791 to strengthen the new nation's credit and improve handling of government finance, but its constitutionality was questioned by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and other "strict constructionalists" in Congress. The building won wide acclaim when completed in 1797 and is considered an early masterpiece of monumental Classical Revival design.

Despite being fifty miles upriver from Delaware Bay, Philadelphia has had a long maritime history and is considered “the birthplace of the U.S. Navy.” The Continental Congress leased land along Front Street for naval defense in 1776, and in 1797 the United States, first of six frigates meant for the new republic’s fledgling navy, rolled down the rails in Philadelphia. A major Naval yard operated in the city for the next two hundred years.

Today, the Independence Seaport Museum honors the city’s maritime history, and preserves a number of historic ships that welcome visitors. The Seaport has faced ongoing challenges preserving the well-appointed cruiser Olympia, the oldest steel warship afloat in the world and an example of advanced naval technology and engineering in its day. Built in 1892, the ship gained fame as Commodore George Dewey’s flagship that won the battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish-American War and asserted American naval power in the Pacific. Across the river rests the battleship New Jersey, open for tours that point to American naval technological prowess in the 20th century.

To get to know Philadelphia as an incubator of invention and experiment, start at the Benjamin Franklin Historic Site, at Franklin Court between Market and Chestnut Streets and 3rd and 4th Streets, to see Franklin’s print shop at work, the post office, and the exhibit of many things Franklin. Franklin was the quintessential “American,” and seeing his world opens up much about the world(s) of Americans as they experimented in science, technology, natural history, and government. From Franklin’s place it is a short stroll to sample much of 18th through early 19th century Philadelphia and America. Go to Elfreth’s Alley, off 2nd Street between Arch and Race Streets, to walk the oldest continuously occupied street in America, with houses that were once occupied by artisans.

The city markets from those early days are gone, but one can get a sense of market days by visiting the New Market between Pine and Lombard Streets. Today, the Reading Terminal Market, at 12th and Arch Streets, occupies a cavernous old train depot, built in 1893 and renovated in the 1980s, and now provides an urban farmers market with a wide variety of food and produce sold by Amish, immigrant, ethnic, and other purveyors in a historic environment. At the same time, the food shops and curbside stands of the Italian Market, on 9th Street between Fitzwater and Wharton Streets, which opened in the early 20th century, recall the Irish, Jewish, and Italian immigrant and ethnic history of the neighborhood that now includes the new immigrants from Asia, the Americas, and Africa selling their foods and wares.

![An important recent acquisition of the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the 1819 portrait of Yarrow Mamout by Charles Willson Peale. Mamout an African American Muslim who won his freedom from slavery and was literate in Arabic. A native of Guinea, Yarrow was “comfortable in his Situation having Bank stock and [he] lives in his own house,” wrote Peale.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Portrait%20of%20Yarrow%20Mamout%20by%20Charles%20Willson%20Peale%2C%201819-detail.jpg)

One can see probably the largest stock of 18th-century to early 19th-century housing still standing in America by walking about Old City and Society Hill. Only the grander buildings remain, but visits to such places as the Bishop White House at 309 Walnut Street and the 1765 Powel House at 244 S. 3rd Street reveal not only the life-style of the social elite but give clues to the lives of those who served them. William White was the first Episcopal bishop of Philadelphia and served as Chaplain of the Continental Congress from 1777 to 1789. His home, now maintained by the National Park Service, was one of the first houses to have an indoor “necessary” at a time when most privies were outside of houses. The Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks, begun in 1931, maintains both the Powel House and the 1786 Hill-Physick House, the only free-standing Federal townhouse remaining in Society Hill.

To appreciate the development of American decorative arts and art, in which Philadelphia has been a leader, through the 20th century, visit the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation, and the Rodin Museum on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts at 118–128 Broad Street, founded in 1805 as the nation’s first art museum and school of fine arts. And throughout the city murals celebrating people, places, and events cover walls, walkways, and other surfaces and give the city a contemporary vibrancy, thanks to the nationally renowned Mural Arts Program.

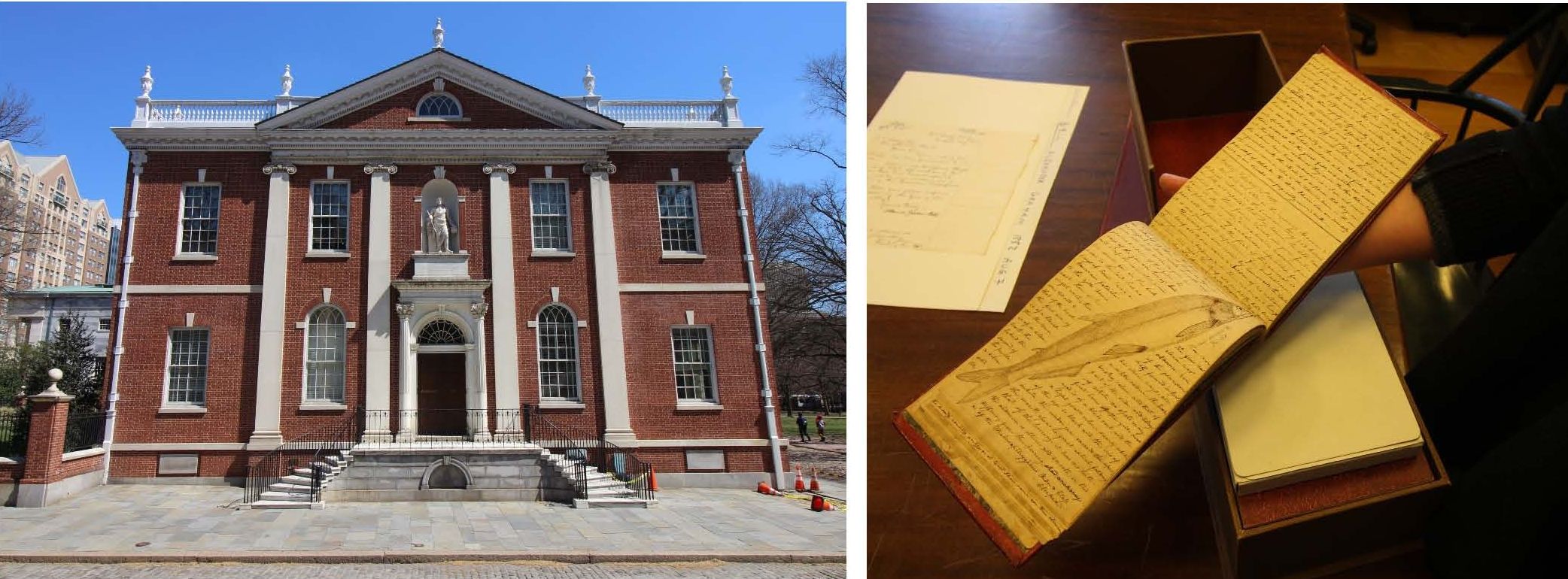

During the 18th through the early 19th century, the clearing house for American scientific inquiry was the American Philosophical Society at 5th and Chestnut Streets, which houses collections on American science, natural history, and even pseudoscience from the 18th century to today.

The practice of collecting specimens as the basis for science continued at the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th Street and the Parkway, the oldest natural history institution in the Western Hemisphere. It is now affiliated with nearby Drexel University.

Also important in gathering essential works is the Library Company of Philadelphia, at 1314 Locust Street, which was founded by Benjamin Franklin and friends as a repository for writings intended for “useful knowledge,” and has vast holdings of all manner of printed works on virtually every subject of interest, with many speaking to ways people sought to reform or remake their mental, moral, and physical worlds from the colonial era into the 20th century.

Next door at 1300 Locust Street, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, founded in 1824 at a time when Americans were furiously gathering up documents, objects, and specimens to discover and preserve their unique “American” history and character, holds one of America’s largest and most important collections of manuscripts, books, and graphic images, which include essential documents on the Revolutionary era, the American Civil War, and immigration and ethnic life, among many subjects.

Also relevant is the early 19th-century experiment in water treatment in Philadelphia, with the installation of the Fairmount Water Works on the Schuylkill River, on Aquarium Drive. A trip to the Franklin Institute at 20th Street and the Parkway will add to understanding about the centrality of technology and science in creating modern living and Philadelphia’s place in that. Philadelphia has long been a major source of invention and production in chemicals, and the Science History Institute at 315 Chestnut Street tracks that history.

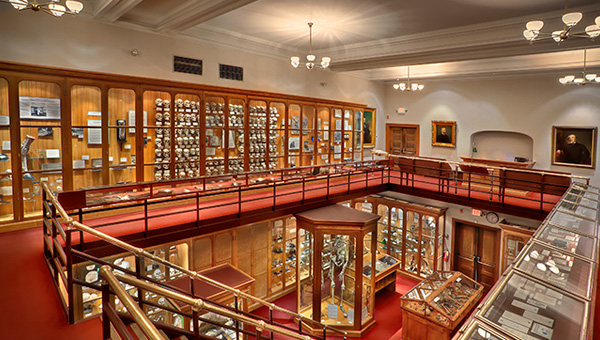

The need to respond to a host of maladies afflicting urban people led to Philadelphia becoming a leader in medicine through the founding of medical schools and societies, several of which continue today. The establishment of a medical profession and training in America was evident in the creation of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia at 19 South 22nd Street, which has a major library for research in medical history and houses the remarkable Mutter Museum, which displays anatomical models, pathological specimens, medical instruments, and many wonders.

Philadelphia also led the way in trying cures for social ills. This was most spectacularly evident in the grand experiment of Eastern State Penitentiary, at 22nd and Fairmount, which was an attempt by Quaker-influenced reformers to house prisoners in an isolated but symmetrically arranged physical environment, where they would contemplate and correct their evil ways and eventually return to society. The experiment failed, and the penitentiary became a prison; it is now a historic site.

From the city’s earliest days, Philadelphians built churches, synagogues, and other sacred places to express their beliefs and shape their communities. To find examples of such diversity for the 17th through the mid-19th centuries, follow the markers tracking the religious sites in Old City and Society Hill. Philadelphia started as a Quaker city. Visit the Arch Street Meeting House on 4th and Arch to see the spare Quaker religious architecture and interior layout, which spoke volumes on Quaker faith and practice. Compare that with the imposing architecture and interior design of Christ’s Church at 2nd and Church Streets, at one time the tallest building in the colonies.

Then amble over to St. Peter’s Episcopal Church at 3rd and Pine Streets, where Bishop William White gave the first reading of the new American Book of Common Prayer asserting an American independence in faith as in polity. Visit St. Joseph’s Chapel in Willings Alley between 3rd and 4th Streets to understand how Catholics hid their public presence in an anti-Catholic world, even as they had permission to worship in Pennsylvania. Then go to Old St. Mary’s on 4th Street between Locust and Spruce Streets to see the second Catholic church built in the city, with its bolder assertion and confidence of place in the new nation. Numerous other Catholic churches bespoke the vigor and variety of Catholic immigrants, with each group wanting priests of their own language.

St. Mary Magdalen de’ Pazzi, at 712 Montrose Street, was founded in 1852 as the first Italian Catholic parish in the country. Other nationality parishes followed, located in concentrations of a particular Catholic ethnic group. The persistent and sometimes violent anti-Catholicism of the 18th and 19th centuries was most evident in the bloody anti-Catholic riots of 1844, which left churches, an orphanage, and homes sacked and burned. St. Augustine’s Church on 4th Street was a special target of such violence. Catholics’ growing importance and confidence survived the attacks and was magnificently expressed in the basilica Cathedral of Sts. Peter and Paul, at 20th Street and the Parkway.

Today, Vietnamese and other Asian Catholics and Spanish-speaking Catholics from Mexico, Central America, and South America worship in some of these churches originally founded to serve Irish, German, Polish, and other European Catholics and have made such churches their own in language and ministry.

There are, of course, many examples of Protestant faith. Some churches were converted to new uses or even claimed by new faiths as immigrants and black migrants moved in. Philadelphia was one of the earliest centers of a vibrant free black community, and African Americans founded their own churches as a means to control their faith and build their communities. One should visit Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church at 6th Street between Pine and Lombard Streets to appreciate its importance as the mother church for a new African American denomination and the font for a host of institutions to sustain both faith and community and to push for social reforms and civil rights.

Jews early on laid down religious roots in Philadelphia, first with the congregation at Mikveh Israel at 44 North 4th Street and then with religious publishing houses and other synagogues. One can learn much about the experiences and contributions of Jews to Philadelphia and American life by visiting the National Museum of American Jewish History at 5th and Market Streets. Similarly, other faiths have established their presence and purpose by building places of worship and institutions such as schools and training their own clergy. Walks in the so-called river wards of the city reveal the variety of churches, synagogues, mosques, and other religious sites marking the city’s religious and ethnic diversity.

Whatever you choose to see within the areas mapped out above, remember that Philadelphia was and is a variegated, diverse, and complicated place and experience. Much of its cultural, social, intellectual, religious, economic, and political history resides outside the “old city” and Center City area. The influx of young people and “empty nesters” to the old city and Rittenhouse Square areas downtown have been creating a “new” Philadelphia, but also in some ways distorting the city’s character, especially its industrial past and often-troubled social history. That said, Philadelphia remains as it began -- an experiment in urban living and defining the American way. In finding Philadelphia, it can become possible to find ourselves.

For a wider view of Philadelphia, and more details and context on places mentioned here, see the digital Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.