-

Winter 2019

Volume64Issue1

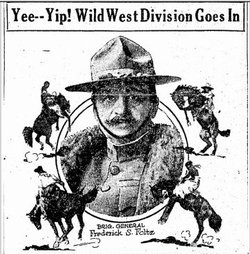

The 91st “Wild West” Division was one of nine American divisions that assaulted German positions in the Meuse-Argonne on September 26, 1918. As befitted its name, the 91st was originally assembled from draftees inducted from the Rocky Mountain west. Their first days in action were indeed wild, as they attacked toward the enemy-held village of Gesnes against well-entrenched machine guns. Green though they were, the westerners fought with honor, but paid an ugly price. Among their number was the father of a future Hollywood movie star.

The Assault Begins

91st Division officers in training, 1917. National Archives

First Lieutenant Frank L. Thompson of Montana, serving with the division’s 348th Machine Gun Battalion, encountered a group of enemy prisoners shortly after the attack began on September 26: “We stopped to rest a little, then our eyes popped out,” he later wrote. “Around a corner in the road came a doughboy and behind was what I took to be the German army. Eventually they proved to be only two hundred prisoners, and one officer. Instead of the brutal, bestial murderers of babies and rapers of women we saw a crown of blond blue-eyed boys and studious looking elderly men with spectacles. They were the meekest crowd to be posing as conquerors of the world I ever hope to see.” But he also encountered American wounded at an aid station: “Several men were there with limbs missing—one heavy weight boxer from Los Angeles had a leg off. He was unconscious.”

On September 27, “at dawn, which broke dull and cloudy, the word came to advance. My platoon was told off to support ‘M’ Company of the 363rd Infantry,” Lieutenant Thompson remembered, “so over the hill we started. We had gone about 200 yards when ‘tst-tst-tst-tst!’ and we did an Annette Kellermann [a famous Austrian actress and diving champion] for Mother Earth. I heard a moan from behind and saw a man trying to get up—then he bent over as though to vomit and the blood gushed out in a stream from his mouth.” For two days the attack bogged down.

Farley Granger Conquers Hell

91st Division Field Hospital, 1918. National Archives

Lieutenant Farley Granger of California, father of the future Hollywood star of the same name, served with the 362nd Regiment. On September 29 his outfit was ordered to assault Gesnes, even though, as he recalled, “up to this time the Regiment had fought for three days without hot food or coffee and but little water and cold food.” Casualties had been heavy, and many of the regiment’s officers considered the attack to be “madness.” As Lieutenant Granger watched, “Captain Montgomery remarked he feared such an advance impossible—that our losses would be terrible. Captain Bradbury answered ‘To hell with the losses—read the order.’”

“Three bare rolling hills stretched toward Gesnes,” Granger observed. “Every square yard was visible from the higher hills beyond, occupied by the enemy, and the concrete pill-box on Hill 255, and every foot swept by machine-gun and artillery-fire. Protection there was none—not even concealment for one man. The gullies between the hills were swept by enfilading fire from the wooded hills above Gesnes, and the hillsides were commanded by nests hidden in the flanks.”

“Bradbury turned to me and quietly said, ‘Well, Farley, lets go.’ I gave the signal to the Company Commanders and, despite the withering hail of steel and lead, as one man the leading Companies rose up and started forward. We moved off directly behind the first wave. Perhaps the charge of the Light Brigade was more spectacular, more melodramatic and picturesque, but not more gallant. Man after man fell but the others continued on through a ‘hell’ of shrapnel and machine gun fire as would be impossible to exceed.

“Unfaltering the line of combat groups rolled steadily on over the open, a trailing wake of olive-drab marking its progress. One must not think of this as happening in an instant—over an hour of this bloody plodding along under a tornado of missiles passed before the worst was over. Finally the last crest was topped, and in irregular groups these Gallant boys swept down the last slope into Gesnes. At the first corner stood a German tank. This was taken and the crew shot as they tried to escape, and its gun turned on a machine gun nest.

“The town was promptly cleared—the satisfaction of some bayonet work was given us. Now, however, with a machine gun bullet through my canteen, four holes through my loose trench coat and one more noticeable through my ankle I made my way back through the still heavy artillery barrage placed to prevent the advance of our Reserves. Dead and dying literally covered the field. Who was responsible for this costly order of attack, why this needless sacrifice of precious lives, was not for us to question.”

A Soldier’s Message to His Son

American Doughboys. National Archives

Years later, in a commentary left for his son, Granger gave tribute to those who died: “Nor are the brave men who now lay forgotten in our Government Hospitals, broken in mind and body as a result of the war, any less heroes, than those who died in battle. Perhaps the sacrifice of the living is even greater. Still they live on; forgotten.

“Do not think me bitter for it is quite natural to forget; that is life. On the contrary, I am exceedingly grateful to have had the privilege of my experiences; and the same ‘something’ that prompted me to go, would always make me feel I had not ‘kept faith’ had I remained at home. And greater than the satisfaction gained at having done my little part as best I could—I received the greatest of all rewards in having made a Mother proud.”

Learn More About the AEF in World War I, and the Lost Battalion at War

Learn more about the AEF in World War I and the famed Lost Battalion, in my upcoming book Never in Finer Company: The Men of the Great War’s Lost Battalion! Please share your email address below. You’ll get monthly emails about research discoveries, book updates, and more.