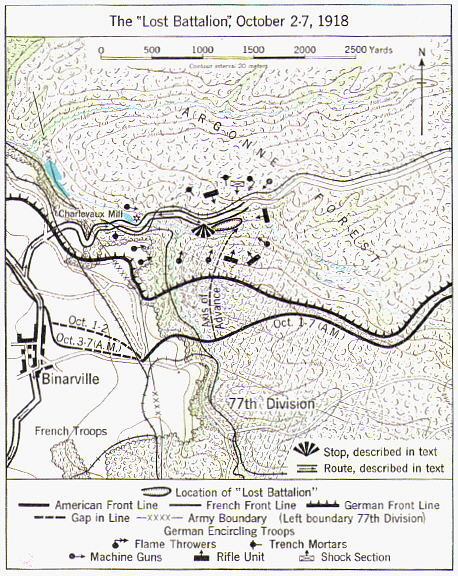

In October 1918, 600 men of the 77th Division attacked a heavily defended German position, charging forward until they were completely surrounded by enemy forces. Only 194 men walked out when they were finally rescued.

-

Fall 2018 - World War I Special Issue

Volume63Issue3

For much of the last ten years, military historian Edward G. Lengel has researched the First World War. Now an independent historian, he wrote a cover article for the Summer 2010 issue of American Heritage on the Meuse-Argonne offensive, “America’s Bloodiest Battle.” Last month, Da Capo Press published his masterful account of the battle and the Lost Battalion’s heroic stand, Never in Finer Company. Mr. Lengel adapted portions of that book for this essay.

--The Editors

In many ways, Maj. Charles Whittlesey was like so many of the other former civilians who made up much of the American officer corps during the First World War. The gangly, bespectacled, thirty-two-year-old New York lawyer had grown up in Wisconsin, attended Williams College, graduated from Harvard Law School in 1908, and settled into a comfortable private practice in New York City. After Congress passed the Selective Service Act on April 28, 1917, he signed up for Reserve officer training.

Now, Maj. Whittlesey was deep in the Argonne Forest commanding a battalion in the 77th Division, the “Metropolitans” made up mostly of New Yorkers. It was a division of almost ridiculous diversity: Chinese, Poles, Italians, Irish, Greeks, Russians, Germans, and Anglo-Saxons. Nearly a quarter of the division was Jewish, many of them draftees from Manhattan’s Lower East Side. There were street toughs, urchins, bartenders, grocers, cops, streetcar conductors, writers, baseball players, stockbrokers, drifters, and blue bloods.

Just before dawn on October 1, Whittlesey assembled his company commanders. The weather was cold but clear. He handed them their orders for the day and briskly said, “Leaders, get your men up!” When the troops assembled he cried, “Everybody ready. Let’s go! Forward!” and they moved out.

Until noon the doughboys had easy going as they pushed up to and over the crest of Dead Man’s Hill. From here the 308th Regiment continued along the swampy north-south Argonne Ravine, which the enemy had plugged with immense coils of barbed wire. Bracken and rough terrain slowed the advance but there was no resistance until mid-morning. Then the enemy machine guns opened fire.

The major heard the shooting and ordered his two lead companies to deploy and outflank the enemy guns. Mortars were useless, and full cover impossible. Enemy observers directed fire on them. One man fell after another, beginning with junior officers. Whittlesey reported the resistance but was ordered to push forward. Dozens more men fell, wounded or dead.

It was just the beginning of one of the most dramatic weeks in American military history.

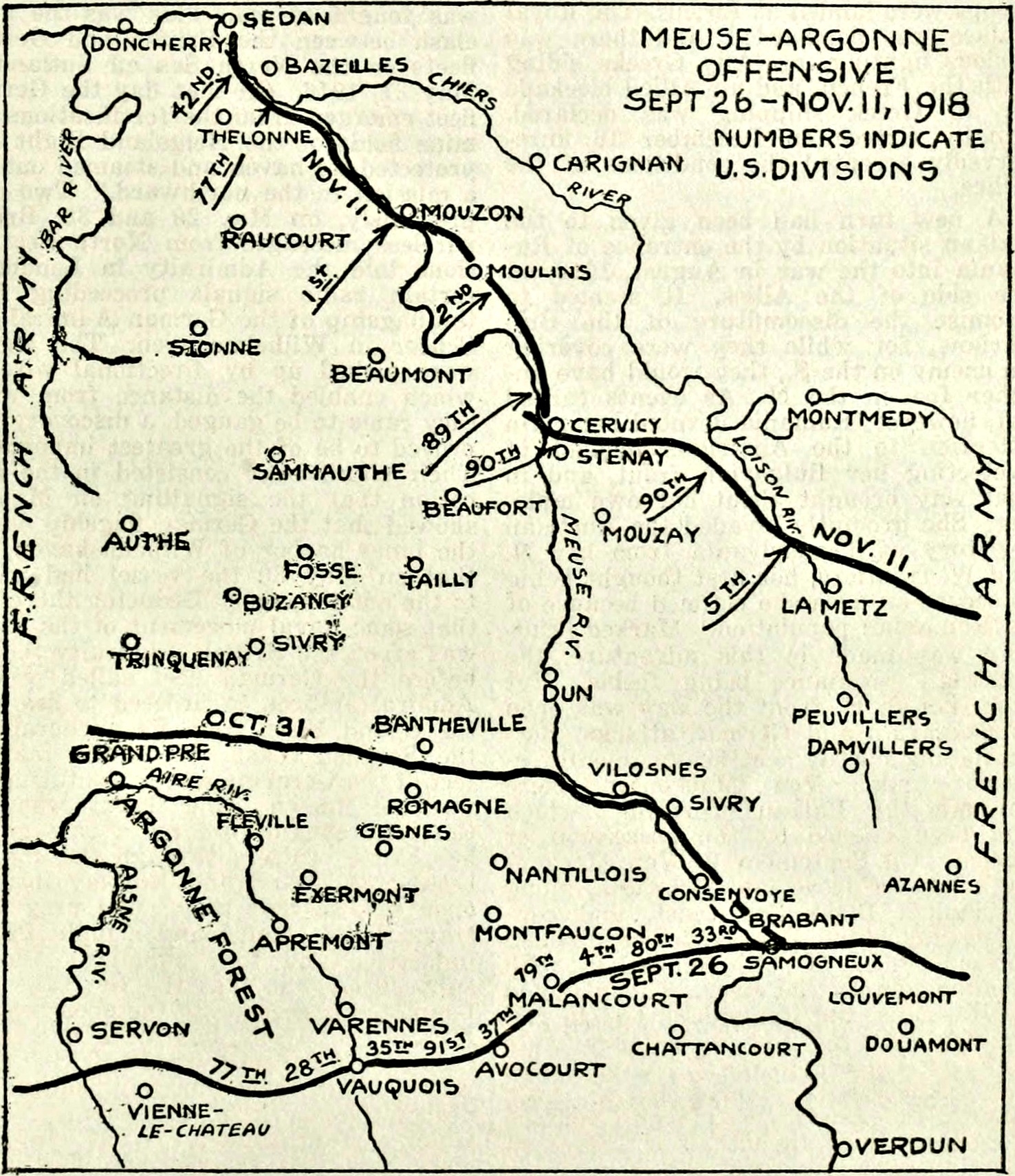

ON SEPTEMBER 26, 1918, some 600,000 Americans had attacked well-trenched German positions in a shell-pitted tract just north of Verdun. Thus began the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the largest American campaign of the First World War. During the following six weeks, more than 1.2 million American soldiers in 22 divisions, including the 77th Division, assaulted German positions in northeastern France. By the time of the Armistice, more than 120,000 soldiers and Marines would fall wounded: 26,277 would die.

The heroism that emerged in those bloody days was extraordinary, as inexperienced and untested recruits and draftees went up against the world’s best-trained and most formidable army in some of the strongest defensive terrain in France. The battle created heroes of ordinary men, the likes of which America had never seen before.

The American forces in the Meuse-Argonne, a region bordered on the east by the Meuse River and on the west by the dense Argonne Forest, comprised the First Army of the American Expeditionary Force, commanded by Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing. Their objective was to break through the German defenses for 40 miles to a critical railway junction near Sedan. Supplies for nearly the entire German army in France passed through this junction; its capture would inflict a severe if not catastrophic blow to Germany’s military fortunes.

The German forces in the Meuse-Argonne were under orders to stop the Americans at all costs. Four brutal years of combat had severely weakened the German army, which in many parts of France held the lines with young boys and old men; but not in the Meuse-Argonne. Initially outnumbered three or four to one, the Germans reacted to Pershing’s offensive by pouring every reserve formation into battle. Their artillery remained the best in the world. Their air formations were strong and vigorous. And they had many thousands of machine guns.

Pershing had expected the initial advance—with the 77th Division moving forward on the American left flank, into the dense Argonne Forest—to take no more than 36 hours, but it bogged down almost immediately in the face of determined resistance. That only convinced him to push harder, driving his forces to exert every nerve, every resource.

Pershing hoped that his troops would demonstrate the superiority of American initiative and fighting spirit. The individual doughboy, he told them, should not put his faith in trenches, artillery, or machine guns but in his rifle, bayonet, and the will to win. Pershing thus put his boys up against a veteran, well-entrenched enemy with many machine guns and little naïveté about the horrors of war. And the Americans’ lack of training in weapons, tactics, and combined arms had bloody results. But it’s wrong to lay it all on Pershing. Many of the problems of Meuse-Argonne resulted from years of unpreparedness and the nation’s late entry into the war.

MUCH OF THE AMERICAN Meuse-Argonne offensive had ground to a halt on September 30. Judged by its progress so far, it was a failure. To the east the Americans had occupied useless ground along the Meuse River without attempting to take the high ground infested by German artillery. These guns fired accurately into the American flank, slowing the advance. In the center, attacking divisions lost a golden opportunity to cut off and capture the German strongpoint at Montfaucon, allowing the enemy to withdraw at leisure. On the left, the 28th Division made only slow progress along the Aire River valley. Casualties were horrendous all along the line.

Meantime, the British and French were making good progress. Why, then, had the American attacks bogged down? Working on the assumptions that the doughboys were superior and the Germans tired, few in number, and short on supplies, Pershing and his commanders concluded that inexperienced American officers were making excuses about lack of support, losses, disorganization, and open flanks. They must be told to stop worrying and push ahead at all costs. Eventually they would break through.

When Whittlesey complained about his flanks not being covered, his men’s fatigue, and enemy resistance, his commanding officer blasted his objections as “nonsense” and restated the orders as given. The major raised more objections and Stacey yelled that he would do as ordered, attacking straight ahead without regard to flanks or cost. It may as well have been General Pershing shouting in the major’s ears. His was not to reason why.

The next morning, after a sleepless night, Whittlesley ordered his men forward. Bullets pinged the ground. Men fell. Mortar rounds exploded, and more soldiers toppled. Enemy machine guns opened fire.

The holding companies to the left took most of the heat at first, but then the Germans on the ridges above fired into the bottom of the ravine and at the assault parties that Whittlesey had deployed to the east. The farther ahead the Americans pushed the worse it got. The enemy guns were well sited and unpressured from either direction. At points, small parties of Germans attacked, inflicted losses, and quickly withdrew.

If he pushed ahead without regard to flanks or losses, Whittlesey knew, every man in his command would die. Just before ten o’clock he sent a courier with a note for the brigade commander, Col. Cromwell Stacey: “Advance held up by machine-gun fire . . . progress impossible without aid from both flanks.”

Col. Stacey, practically trembling with stress and fatigue, read Whittlesey’s report and fumed, knowing how it would be received further up the line. He phoned the major’s report to General Johnson, who listened in silence and hung up. Johnson phoned divisional headquarters. General Alexander was away for the moment, but staffers shook their heads disgustedly.

Whittlesey was talking to some of his men in hastily dug funk holes when a second lieutenant found him and handed over a message from Colonel Stacey. “The commanding general is dissatisfied with your rate of progress” the note said. The attack must resume immediately.

Whittlesey’s features hardened but he remained calm. He walked back up the ravine to the battalion headquarters. “It will only lead to the same thing again—” the major exclaimed, remembering his recent ordeal. “We’ll be cut off!”

Stacey, who was far nearer collapse than the major, interrupted. “You’re just getting panicky,” he said. “Proceed with the attack as ordered, Major!”

“Alright, I’ll attack,” Whittlesey said; “but whether you’ll hear from me again I don’t know.”

Three hours after the American attack began, forward parties approached the north end of the ravine. Only then did Whittlesey appreciate the scale of their casualties. Although only eight men had been killed, ten times that number were wounded; most lying in the bracken but a few still stumbling forward. Whittlesey gave no thought to stopping or even slowing down, however; the general said push; he must push. Casualties and flanks meant nothing.

Then the incredible happened.

Topping a rise alongside the ravine’s north edge, the major discovered a deep, formidable German trench system. It was empty, with not a German soldier in sight. Ahead lay a wooded east-west valley, also apparently uninhabited. They had broken through!

Whittlesey realized they were advancing into a gap in the German line. The way ahead was clear, and if the flanks seemed dicey they must count on their neighboring battalions to clean them up—that was all.

Daylight found Whittlesey wide awake and conferring in a funk hole with Captain George McMurtry, a company commander whom he placed in overall charge of the perimeter. Someone produced a precious carton of Salisbury cigarettes, and the men of the headquarters detachment lit up.

Elsewhere around the perimeter men used the growing daylight to put the finishing touches to their funk holes, checked ammunition and lines of sight, chatted quietly with each other, or slept.

They wondered when the rations would arrive.

Whittlesey sent his sergeant major, grocery store clerk Ben Gaedeke of Yonkers, son of German immigrants, to check on how many men he had lost the previous day, and how many were left.

The answers: about one hundred casualties, and about five hundred fit for duty.

THE DOUGHBOYS CAUGHT brief glimpses of German troops rushing in small parties around the flanks—not north, away from the fighting, but south into the ravine.

A whistle, a whump, and crash of branches and debris stunned the men in Whittlesey’s command hole. Another explosion followed, and another. For a few minutes, everyone wondered if the enemy artillery had somehow managed to find them on the reverse slope. Then it began to register that these shells were coming from one weapon—not ahead, but behind. It was “friendly fire.” Only now did they realize that all the runners they had sent back to headquarters had fallen victim to the enemy.

To ensure everyone knew the stakes, Whittlesey passed this message on to all of his company commanders: “Our mission is to hold this position at all costs. No falling back. Have this understood by every man in your command.”

The devastating truth behind that favorite military cliché, “at all costs,” soon became apparent.

At around three o’clock, the American outposts just below the road heard sounds of movement atop the ridge. After a few minutes of silence, grenades tumbled though the foliage and a series of explosions drove the Metropolitans deeper into their funk holes. They waited, but nothing happened at first. A few minutes later, more rustling in the underbrush, this time intermixed with German voices, became apparent to the right and left as well as above.

Not realizing how many of their own former countrymen now wore American uniforms, the Germans carelessly called out commands that doughboys translated and whispered along the lines. Machine guns were primed and sited along probable axes of attack. Former grocers, laundrymen, cowboys, clerks, and college athletes settled deeper into their holes, held their rifles, kept their eyes open, and waited. When the assault came they were ready.

German rifles and machine guns opened fire all along the perimeter, including some recently placed in the valley behind. Grenades tumbled in again from above, left, and right. But the Germans were firing blind. In a few places they scored lucky hits, but for the most part the bullets and shells were absorbed by the underbrush and the trees. If a man kept his head down, he was probably okay. Only just below the road did the doughboys present easy targets. Several of them scrambled down the hill to take cover in the underbrush farther downslope.

As soon as the American machine gun positions became apparent, German machine guns targeted them with counterfire.

The enemy mortarmen watched carefully too, and not many minutes passed before well-directed shellfire peppered the pocket, silencing one machine gun after another. German infantry followed this up by rushing the suppressed guns. In a few cases the American crews abandoned their weapons. At other points, they stuck to the guns doggedly, but at severe cost.

Night settled in over a pocket filling with an increasing sense of dread. Although the men were exhausted and desperate for rest, now that silence had come the hours seemed to drag. These were the moments that they experienced most intensely. They were also the most powerfully shared. In the years to come, veterans of the Argonne pocket especially would remember the nights.

They lived stories that could never be told, except to other men who had been there, and that was a solace.

ELSEWHERE, THE REMAINDER of First Army spent the first few days of October resting, but not the Metropolitans, and now they had simply reached their physical limits. Only the French, well-trained in the art of conserving energy and resources, refused to give up. To Whittlesey’s left rear the French launched persistent attacks that failed to break the German lines but applied so much pressure that the enemy had to divert reserves in that direction and so postpone active operations against the pocket.

None of the men in the pocket knew about the stalled French and American attempts to relieve them. The sound of distant shellfire was more or less constant, and often drowned out by shelling closer at hand.

Noon passed. Food was a memory. Soldiers scraped invisible remnants from ration tins they had scraped several times before, and searched pockets and haversacks they had already turned inside out. The sky, incredibly, was blue; but though they scanned frequently no one saw an airplane. The doughboys looked through the trees for approaching enemy, or for the patrols heralding the dreamed-for relief. They saw nothing but kept looking.

Men watched in shifts while their buddies tried to sleep, and the wounded struggled to rest. The Germans seemed quiet too. It was a waiting game.

The mortar fire stopped, then the machine guns. After a pause, as if on cadence, dozens of grenades rained down. Some were tied together in bunches. Explosions erupted in staccato rhythm along the perimeter, and then running German boots thumped the tortured earth among the trees. The enemy came from every direction.

Charles Whittlesey did not lose heart. Deeply conscious of the sufferings of his men, whether wounded or not, he took upon his own shoulders the responsibility to engage with each and every one of them and do what he could to help. When not assessing the tactical situation, assigning patrols and other duties, or carrying them out himself, he crawled from hole to hole to talk with the men. Downtime, opportunities for rest and sleep, did not exist for him. Whittlesey provided first aid when he could, and shared anything he had with a man who needed it, keeping nothing for himself.

His dedication, and that of other officers such as Capt. McMurtry, would determine whether the Lost Battalion survived. But for Whittlesey, the ultimate cost would prove too much to bear.

Portions of this essay were adapted by the author from Never in Finer Company: The Men of the Great War's Lost Battalion by Edward Lengel. Copyright ©2018. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.