The great war correspondent, who died 75 years ago during the battle of Okinawa, had a knack for connecting with everyday people, both on the front lines and at home.

-

Spring 2020

Volume65Issue2

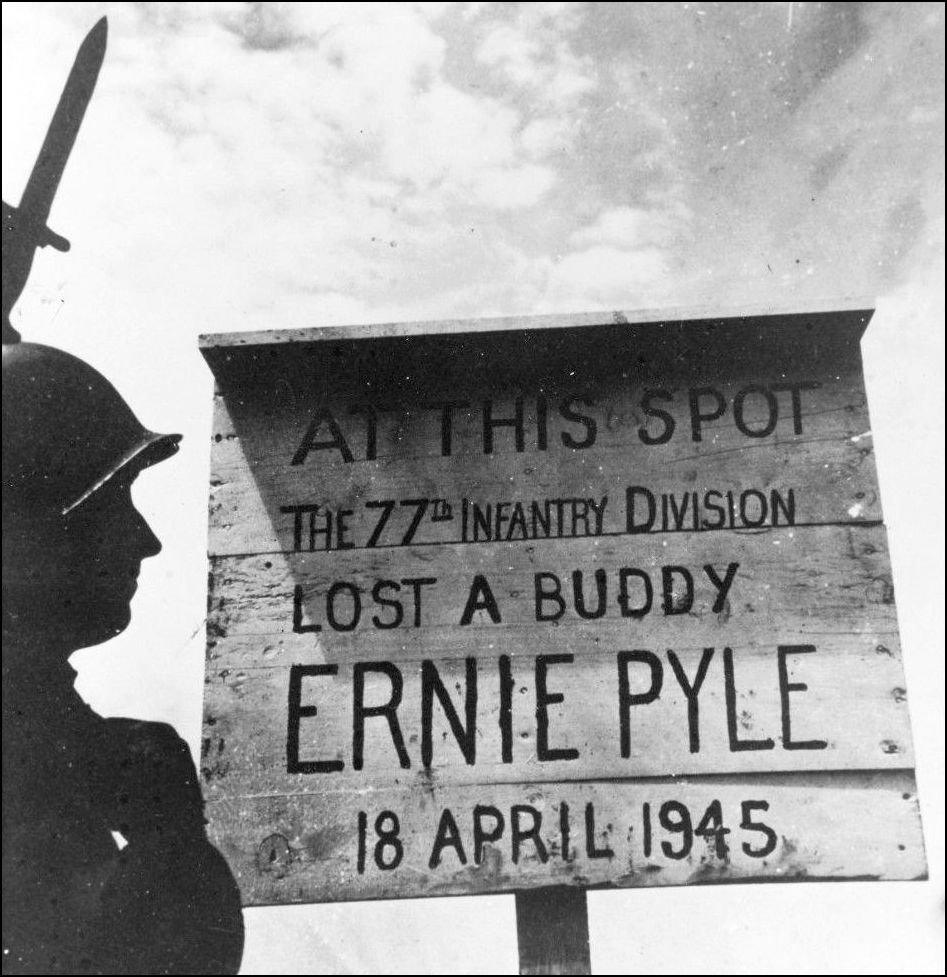

Near the end of World War II, as my father's fleet tugboat steamed by Le Jima Island off Okinawa in the Pacific, he noted in his journal that this was “where Ernie Pyle was killed.”

That was just one tiny indication of how revered this Scripps-Howard war correspondent was at the time he was killed 75 years ago on April 18, 1945 by a Japanese machine gunner on the island.

Many journalists are admired for the work they have done, but few were as beloved across the United States for bringing the humanity and truth home to readers by reporting it through the eyes of the average GI.

“Pyle honed a sincere and colloquial style of writing that made readers feel as if they were listening to a good friend share an insight or something he noticed that day,” David Chrisinger wrote for the New York Times in 2019.

Millions of readers followed Pyle’s daily column in about 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers across the United States. In May 1944 he received the Pulitzer Prize, honored by his peers for the enduring quality of his work in the face of overwhelming difficulties.

“Ernie Pyle’s greatness lay in his ability to connect with everyday people, both on the front lines and at home,” says Michael Freedman, President of the National Press Club. “He was one-and-the-same with those he covered and those for whom he wrote.”

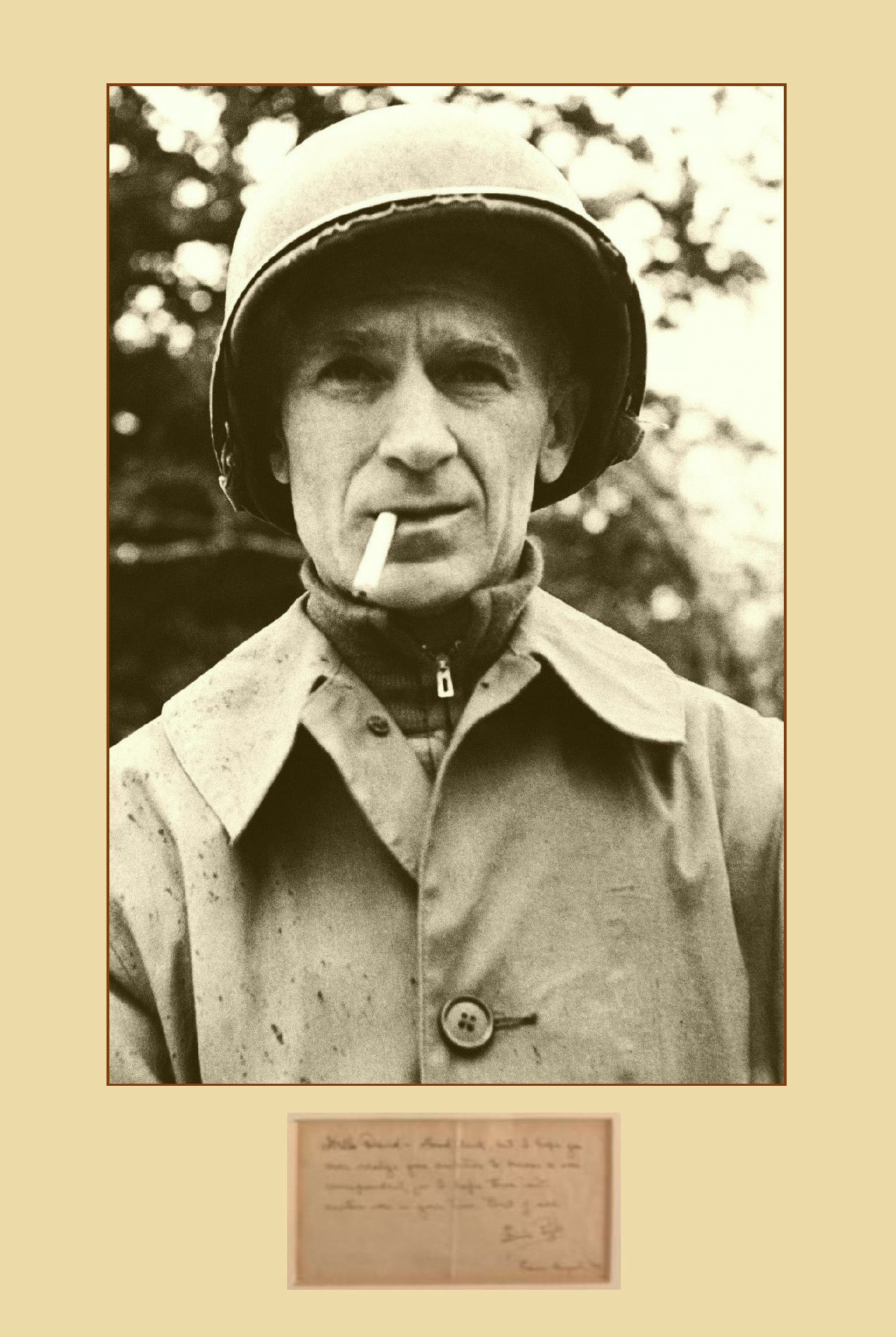

The Press Club displays a collection of photos and memorabilia about Pyle, including a framed photo of the correspondent in battle helmet and fatigues with a cigarette hanging out of the right corner of his mouth. This must be how so many soldiers saw him.

Underneath the photo is a handwritten note in response to an aspiring young journalist who had told him he too wanted to be a war correspondent. Pyle wrote: “Hello David – Good luck, but I hope you never realize your ambition to become a war correspondent, for I hope that there isn’t another war in your time. Best to all, Ernie Pyle France, August, 1944.”

“That speaks volumes about his character and the impact of war on a superb journalist who cared,” Freedman says.

“Ernie Pyle was the closest thing to a soldier that a reporter could be,” says Vietnam War veteran Jim Noone. “He shared jokes, smokes and foxholes with them, stood in the chow line, was alongside them in harm’s way. They considered him one of their own, and confided in him their hopes and fears.”

Pyle’s most famous column eulogized Army Capt. Henry Waskow, company commander in the 36th Infantry Division, who died on Dec. 14, 1943 when he was struck in the chest by a German mortar in the mountains south of Rome.

“Pyle knew when to let a scene speak for itself, and the starkness he chose to describe this one only added to their weight and power,” as he waited at the bottom of a mountain while dead soldiers were transported down by mules, writes Gregory Sumner, a professor history at the University of Detroit Mercy.

The column read in part:

Sumner says that the intimate, closely-observed details of this column struck such a chord with the readers that Arthur Godfrey read it aloud on his syndicated radio program, and it was adopted for war bond drives. The National Society of Newspaper Columnists selected it as "the best American newspaper column of all time."

Pyle usually spared his reader from the gruesome details of the carnage of battle. But as Chrisinger pointed out, by his third column after coming ashore, he smacked his readers in the face with what he observed on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

“It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore,” he wrote, reeling the reader in with a cheerful opening, Chrisinger noted. “Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever. Men were floating in the water, but they didn’t know they were in the water, for they were dead.”

Ernest Taylor Pyle was born on Aug. 3, 1900 near Dana, Indiana. His boyhood home is now a small museum. He enlisted in the Navy in World War I, but the war ended before he finished his training. At the University of Indiana, he developed his story-telling writing style while working on the student newspaper.

He left school one semester short of graduation to take a job with the LaPorte Herald in Indiana, but in three months, he was in Washington, working for the Scripps-Howard owned Washington Daily News, where he became managing editor from 1932 to 1935.

After an extended trip across the country, he wrote a series of columns about everyday people, and they were so well received that he left the Daily News to ride around North America with his wife, Jerry, writing columns for Scripps-Howard. As an aviation columnist, he flew about 100,000 miles as a passenger, leading Amelia Earhart to say, “Any aviator who didn’t know Pyle was a nobody.”

He was in London in 1940 writing about the Battle of Britain and returned to Europe in 1942 as a Scripps-Howard correspondent, joining in on the North Africa invasion and the Italian campaign before D-Day.

Exhausted from the combat stress, he returned to the United States in September 1944 to recuperate, and then only reluctantly agreed to go to the Asiatic-Pacific Theater in January 1945.

He wrote about the horrific battle for Okinawa, but on April 17, he landed on the small island of Le Jima, which supposedly had been subdued of Japanese.

It was not.

Pyle was traveling in a jeep with four Army officers when it came under machine gun fire. Taking cover in a ditch, Pyle looked up to see what was happening. He was shot through the head and died instantly.

President Harry Truman, in office only a week when Pyle died, paid this tribute: “No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen.”

To learn more:

The Man Who Told America the Truth About D-Day, by David Chrisinger, New York Times, June 5, 2019

Visit davidchrisinger.com/latest-work/the-man-who-told-america-the-truth-about-d-day/