Largely unknown to his cabinet, Ronald Reagan broke with previous U.S. policy and initiated a global campaign of economic and political warfare against the Soviets.

-

Winter 2020

Volume64Issue1

The Soviet Union was erased from world maps not because of a reform process or a series of diplomatic arrangements. It simply could not sustain itself. Historians will debate for decades, perhaps centuries, which factors weighed most on the Soviet system. Was it the bankruptcy of State ideology? Was failure preordained because communism was so contrary to human nature? Did the calcified and rusting Soviet economy finally bear such a burden that it imploded, much like a weak roof collapsing under the burden of heavy snow?

The answer, in short, is all of these explanations and many more. What is clear is that one central, chronic problem for the Kremlin throughout the last decade of its existence was the resource crisis. The Soviet system had been able to limp along quite well until the 1970s. Yes, there were never-ending food shortages and inefficient factories all along. But by the 1980s, these economic difficulties became intractable. It was Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempt to confront this fundamental problem that ushered in perestroika and glasnost. Absent this systemic crisis, Gorbachev never would have begun his walk down the path of change.

Some believe that little or no connection can be drawn between American policies in the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet edifice. As Strobe Talbott put it on the talk show Inside Washington: “The difference from the Kremlin standpoint ... between a conservative Republican administration and a liberal Democratic administration was not that great. The Soviet Union collapsed: the Cold War ended almost overwhelmingly because of internal contradictions or pressures within the Soviet Union and the Soviet system itself. And even if Jimmy Carter had been reelected and been followed by Walter Mondale, something like what we have now seen probably would have happened.”

Former Soviet officials do not share this view. Oleg Kalugin, a former KGB general, says “American policy in the 1980s was a catalyst for the collapse of the Soviet Union.” Yevgenny Novikov, who served on the senior staff of the Soviet Communist Party Central Committee, says that Reagan administration policies “were a major factor in the demise of the Soviet system.” Former Soviet Foreign Minister Aleksandr Bessmertnykh told a conference at Princeton University that programs such as the Strategic Defense Initiative accelerated the decline of the Soviet Union.

Reagan administration policy vis-a-vis the Soviet Union was in many ways a radical break from the past. What is only now emerging is the fact that the United States had a comprehensive policy to exacerbate the crises faced by the Soviet leadership. That policy took many forms: hidden diplomacy, covert operations, a technologically intense and sustained buildup, as well as a series of actions designed to throw sand in the gears of the Soviet economy. At the same time, Washington was involved in a number of high-stakes efforts to eat away at the Soviet periphery, in effect to roll back Soviet communism not only in the third world but at the heart of the empire.

Ronald Reagan (to state the obvious) had a passionate dislike for Marxism-Leninism and the Soviet “experiment.” He believed that communist regimes were not “just another form of government,” as George Kennan put it, but a monstrous aberration. “President Reagan just had an innate sense that the Soviet Union would not, or could not survive,” recalls George Shultz. “That feeling was not based on a detailed knowledge of the Soviet Union; it was just instinct.”

Ronald Reagan, a moon calf to most American intellectuals, was surprisingly correct in his assessment of the relative health of the Soviet regime. “The years ahead will be great ones for our country, for the cause of freedom and the spread of civilization,” he had told students at Notre Dame University in May 1981. “The West will not contain communism, it will transcend communism. We will not bother to denounce it, we’ll dismiss it as a sad, bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages are even now being written.” In June 1982, he told the British Parliament that Marxism-Leninism would be left on the “ash heap of history” and predicted that Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union itself would experience “repeated explosions against repression.”

Contrast those statements with the views of America’s leading intellectuals. Arthur Schlesinger declared after a 1982 visit to Moscow, “I found more goods in the shops, more food in the markets, more cars on the street—more of almost everything, except, for some reason, caviar. ... Each superpower has economic troubles; neither is on the ropes.”

Noted economist John Kenneth Galbraith made a similar assessment in 1984. “The Russian system succeeds because, in contrast to the Western industrial economies, it makes full use of its manpower,” he noted. “The Soviet economy has made great national progress in recent years.” And Professor Lester Thurow at MIT claimed as recently as the late 1980s in his textbook The Economic Problem: “Can economic corn- - mand significantly compress and accelerate the growth process? The remarkable performance of the Soviet Union suggests that it can. In 1920, Russia was but a minor figure in the economic councils of the world. Today it is a country whose economic achievements bear comparison with those of the United States.”

Ronald Reagan’s belief in the fundamental weakness of the Soviet system appeared in more than his speeches; it was translated into policy. The Reagan administration wanted to use Soviet weaknesses to its strategic advantage. Communism was torn by fatal contradictions. It had global and military ambitions but also faced internal economic and resource problems. If pressed hard enough, the Kremlin would be forced to choose between maintaining its global empire and solving its domestic problems.

In early 1982, President Reagan and a few key advisers began mapping out a strategy to attack the fundamental economic and political weaknesses of the Soviet system. “We adopted a comprehensive strategy that included economic warfare, to attack Soviet weaknesses,” recalled Caspar Weinberger. “It was a silent campaign, working through allies and using other measures. It was a strategic offensive, designed to shift the focus of the superpower struggle to the Soviet bloc, even the Soviet Union itself.”

The goals and means of this offensive were outlined in a series of top-secret national security decision directives (NSDDs) signed by President Reagan in 1982 and 1983. Never one for details, Reagan decided where the tracks should lead, the National Security Council staff built the railroad, and William Casey and Caspar Weinberger made sure the train arrived at its destination.

The strategic offensive hatched in the early days of the Reagan presidency attacked the very heart of the Soviet system and included:

- Covert financial, intelligence, and logistical support to the Solidarity movement in Poland that ensured survival of an opposition movement in the heart of the Soviet empire;

- Substantial financial and military support to the Afghan resistance, to take the war even into the Soviet Union itself;

- A campaign to reduce dramatically Soviet hard currency earnings by driving down the price of oil with Saudi cooperation and limiting natural gas exports by the Soviets to the West;

- A sophisticated and detailed psychological operation to fuel indecision and fear among the Soviet leadership;

- A comprehensive global campaign, including secret diplomacy, to reduce drastically Soviet access to Western high technology;

- A widespread technological disinformation campaign, designed to disrupt the Soviet economy; and

- An aggressive high-tech defense buildup that by Soviet accounts severely strained the economy and exacerbated the resource crisis.

The design and implementation of these policies was in many instances confined to a few individuals on the National Security Council and in the cabinet. “Few of these initiatives were discussed at cabinet meetings,” recalled Bill Clark. “The president made his decisions with two or three advisers in the room.” Secretary of State George Shultz, for example, learned about the Strategic Defense Initiative only hours before the public did. That the United States was providing covert aid to Solidarity was known by only a few on the NSC. The critical decision to encourage and aid the mujahedin-military strikes inside the Soviet Union was never discussed by cabinet members. The president simply discussed it with Clark and Casey, then made his decision.

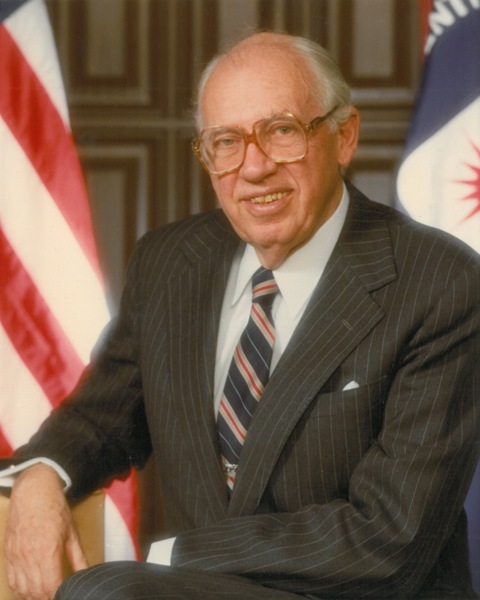

Because a significant portion of the Reagan strategy made use of covert operations, CIA Director Casey was at the center of carrying out the strategy. He was easily the most powerful CIA director in American history and had personal access to the president. Because of the comprehensive nature of the strategy and the covert methods being used, Casey oftentimes ventured into the areas of foreign policy traditionally reserved for other cabinet members. “Bill Casey sort of ran his own State Department and his own Defense Department,” recalls Glenn Campbell, the chairman of the President’s Intelligence Oversight Board during the 1980s. “He was everywhere, doing everything. ‘CIA director’ was only a label, not a job description.”

It was Casey who managed several key elements of the Reagan strategy, including covert operations in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Afghanistan. Much of what Casey was involved in was shrouded in secrecy—even to some of the president’s top aides. “You never knew about Bill Casey’s movements,” recalls Richard Allen, who served as Reagan’s first national security adviser. “He had that inconspicuous black plane, which had living quarters inside. He flew around the world doing everything imaginable. Even the president didn’t know where he was sometimes.”

Casey’s obsession was not a recent acquisition. It extended back to his experiences during the Second World War, when he had served in the Office of Strategic Services. At the age of 32, he had been in charge of coordinating covert intelligence operations in Europe. For Casey, Soviet communism was not a new threat but part and parcel of the menace posed by Nazi Germany. “He clearly saw this as a continuation of what he had left undone after the Second World War,” says Alan Fiers, who served in operations on the Arab peninsula until the mid-1980s before being transferred to Central America. “That’s the way he saw the directorship; as a chance to continue on in the fight.”

Then there was Caspar Weinberger, a longtime Reagan friend and aide. Weinberger had a strong appreciation for technological innovation and dislike for communism. In his mind, technological innovation was a distinct American advantage that could and should be used to strain the Soviet economy.

“Playing to our strength and their weakness, that was the idea,” recalls Weinberger. “And that means economics and technology,” shifting the emphasis in the East-West military competition from quantity to quality. Weinberger believed that American technological innovation in the military sphere, if allowed to run unhindered, would leave Moscow desperately behind. In top-secret Pentagon documents, Weinberger referred to this as a form of “economic warfare.” He understood the technological weaknesses in the Soviet system and wanted to exploit them.

The defense buildup Weinberger orchestrated was not characterized by a simple increase in the budget. How money was spent was as important as how much. What bothered Moscow, according to Gen. Makhrnut Akhmetovich Gareev, was a defense buildup “sharply intensifying ... at a pace and in forms never noted before.” Weinberger was also a firm believer in the Soviet Union’s inability to muddle along without inputs of credit and technology from the West. At every opportunity he pushed aggressively for restricting transactions between East and West as much as possible.

Casey and Weinberger figure prominently in the strategy if only because they were members of Reagan’s first cabinet and stayed with the president well into his second term. Institutionally it was the Reagan National Security Council that played the sharpest role in formulating the strategy. National Security Adviser William Clark, a longtime Reagan friend who lacked establishment foreign policy credentials but had keen insights, oversaw the drafting of some of the most important elements of the strategy. NSC staffers were pivotal in the formulation of the strategy. Robert McFarlane and Adm. Poindexter, who followed Clark as national security adviser, kept critical elements of the strategy intact and functioning into the second Reagan term.

Perhaps uniquely among modern-day presidents, Ronald Reagan did not view arms control agreements and treaties as the measure of his success in foreign affairs. He had little time for most arms control proposals and viewed the East-West struggle as a titanic battle between good and evil.

The fact that the greatest geopolitical event since the end of the Second World War happened after eight years in the presidency of Ronald Reagan has been described as “dumb luck.” One recalls that when the exploits of a French commander who was unpopular with his colleagues were dismissed as “luck,” Napoleon retorted, “Then get me more ‘lucky’ generals.