Critics saw him as weak, but in his one term in office Carter had significant achievements in foreign affairs and environmental and energy policy.

-

November 2020

Volume65Issue7

Editor’s Note: The author was a longtime columnist and senior editor at Newsweek, and since has been a television commentator, documentary filmmaker and author of three New York Times bestsellers. Portions of this essay appear in his latest book, His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life.

Throughout Jimmy Carter’s long life, classmates, colleagues, and friends — even members of his own family — found him hard to read. The enigma deepened in the presidency.

Carter was a disciplined and incorruptible president equipped with a sharp, omnivorous mind; a calm and adult president, dependable in a crisis; a friendless president who, in the 1976 primaries, had defeated or alienated a good portion of the Democratic Party; a stubborn and acerbic president, never demeaning but sometimes cold; a nonideological president who worshipped science along with God and saw governing as a series of engineering problem sets; an austere, even spartan president out of sync with American consumer culture; a focused president whose diamond-cutter attention to detail brought ridicule but also historic results; a charming president in small groups and when speaking off the cuff but awkward in front of a teleprompter and often allergic to small talk and to offering a simple “Thank you”; an insular, all-business president who seemed sometimes to prefer humanity to human beings but prayed for the strength to do better.

For some in Carter’s orbit, his impatient and occasionally persnickety style — a few dubbed him “the grammarian in chief” for correcting their memos — would mean that their respect would turn to reverence and love only in later years. Only then did many of those who served in his administration fully understand that he had accomplished much more in office than even they knew.

Carter’s farsighted domestic and foreign policy achievements would be largely forgotten when he shrank in the job and lost the 1980 election.

He forged the nation’s first comprehensive energy policy and historic accomplishments on the environment that included strong new pollution controls, the first toxic waste cleanup, and doubling the size of the national park system. He set the bar on consumer protection; signed two major pieces of ethics legislation; carried out the first civil service reform in a century; established two new Cabinet-level departments (Energy and Education); deregulated airlines, trucking, and utilities in ways that served the public interest; and took federal judgeships out of the era of tokenism by selecting more women and blacks for the federal bench than all of his predecessors combined, times five.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whom he appointed to the appellate court, said Carter “literally changed the complexion of the federal judiciary,” though he never had a Supreme Court vacancy to fill. Carter did the same for the executive branch, while empowering for the first time the vice president and the first lady, both of whom were given far more responsibilities than any of their predecessors.

So much legislation passed on his watch that major bill-signing ceremonies — a rarity in later administrations — were greeted by the jaded press with yawns. While Carter served only one term, he was, unlike Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, backed by a Democratic Congress for all four years, with a Senate where filibusters were rare. This meant that for all of his problems, he enacted more of his agenda than any postwar American president except Lyndon Johnson, whose legislative program was so big it made the next Democratic president’s look underwhelming by comparison.

Even little-publicized Carter bills changed parts of American life, from requiring banks to invest in low-income communities to legalizing craft breweries. While Carter suffered several painful defeats — on tax reform, welfare reform, consumer protection, and health care — he won much more than he lost. This scorecard went largely unnoticed, in part because the aggressive post-Watergate press tended to assume the worst about him.

Carter was a Democratic president, but he accomplished many things commonly associated with Ronald Reagan. It was Carter, not Reagan, who ended rampant inflation by appointing Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board; Carter, not Reagan, who cut the deficit and the growth rate of the federal workforce; Carter, not Reagan, who first broke with the Richard Nixon—Henry Kissinger policy of detente with Moscow by inviting Soviet dissidents to the White House and building the MX missile.

Contrary to his reputation, Carter — after some hesitation — showed toughness by placing intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe. His Pentagon developed the B-2 stealth bomber and other high-tech weapons that the Soviet Union could not match. He sharply increased the defense budget and approved covert aid to anti-Communist Afghan rebels — the mujahideen — who helped turn Afghanistan into the Soviet Union’s Vietnam.

And yet Carter also took risks for peace — and paid a political price for avoiding escalation, most conspicuously in the case of the Panama Canal Treaties. Ratified despite fierce opposition, the treaties prevented the deployment of more than a hundred thousand troops to the Canal Zone and dramatically improved the image of the United States across Latin America.

Carter was the first president with a policy devoted explicitly to promoting individual human rights in other countries. While applied unevenly, the new approach helped hasten the demise of more than a dozen dictatorships, gave hope to dissidents worldwide, and set a new and timeless global standard for how governments should treat their own people. Conservatives who had once thought it naive later admitted that the policy helped win the Cold War. And in the wake of the Vietnam War and CIA abuses that left the United States deeply unpopular in many parts of the world, the humble and respectful approach of the Carter administration offered a model for repairing America’s global reputation in the 2020s.

Carter himself made a good argument that his most lasting foreign policy achievement was walking through the door that Richard Nixon had opened to China in 1972. He ended Nixon’s and Gerald Ford’s unworkable “two-China policy” (which tilted toward Taiwan) and established full diplomatic relations with Peking, a move that launched the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

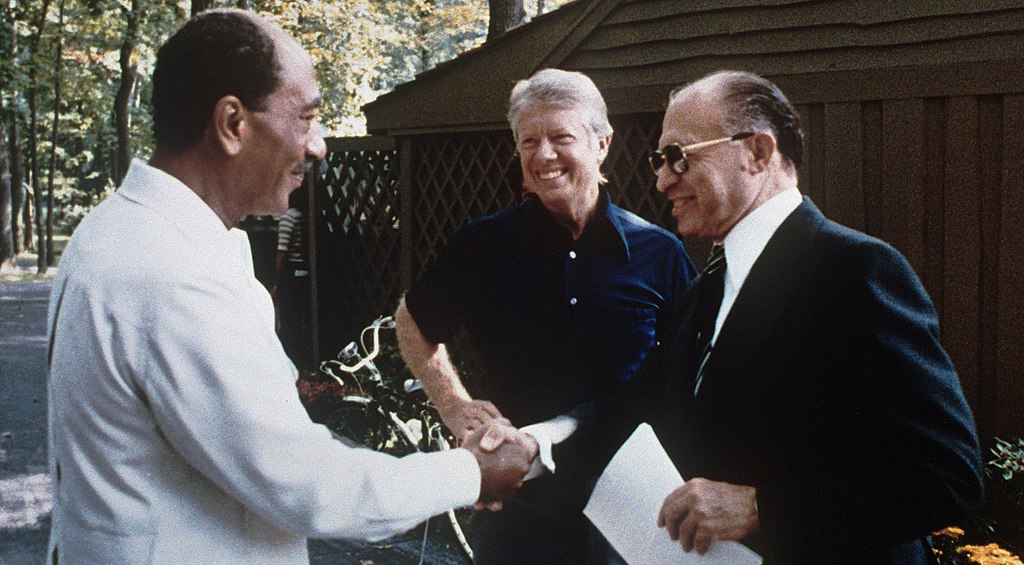

Four decades on, the 1978 Camp David Accords survive as a world-historic achievement — the most successful peace treaty since the end of the Second World War. On at least three occasions, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat or Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin packed their bags to leave Camp David and wreck the summit. Over and over, Carter’s inspired tenacity — his wheedling, cajoling, improvising, insisting — saved the day. Franklin Roosevelt’s wartime diplomat, Averell Harriman, exulted, “What he has done with the Middle East is one of the most extraordinary things any president in history has ever accomplished.”

Few remember that the deal nearly collapsed after Camp David. Six months later, at great political risk, Carter traveled to Cairo and Jerusalem and painstakingly put the whole thing back together. After his presidency, Israelis and American Jews grew concerned about Carter’s pro-Palestinian sentiments. But deeds are more important than words. The Israelis and Egyptians have not fired a shot in anger in more than forty years.

Beyond faith, ambition, and grit, there was one constant in the complexity of his story. Today almost every politician wants to be seen as an outsider; Carter was the real thing. As a six-year-old, he was viewed as a country bumpkin when he ventured from his farm in tiny Archery, Georgia, to go to school in the daunting metropolis of Plains, population 406. He was a defiant outsider at the Naval Academy, where he was hazed more viciously than most other plebes, and at sea, where his shipmates thought he spent too much time reading manuals in his bunk. Back in Plains, his tolerant views on race set him outside the circle of his white supremacist neighbors, and in the Georgia State Senate, he never joined the poker games.

When, after a period of depression and a born-again experience, he went door-to-door as a Baptist missionary in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, his accent stuck out. He was elected governor by campaigning against Atlanta’s insider “big money boys,” then became a pariah to the rednecks who had put him in office. Beginning at 0 percent in the polls, he essentially invented the now-commonplace outsider presidential bid, which was both a campaign strategy and an authentic reflection of his nature. And in office, he avoided clubby relations with Congress and the Washington establishment.

Even Carter’s political orientation lay outside the standard categories. He wasn’t an angry populist, like his grandfather’s patron, Tom Watson, or a devotee of the New Deal, which his father came to loathe. His political roots are easier to discern in the progressive traditions of the turn of the twentieth century, which stressed reform and rejection of special interests. The rest was hard to pigeonhole: he shared Theodore Roosevelt’s conservationist ethic and championing of health and safety regulation; Woodrow Wilson’s diplomatic courage and global ideals; Calvin Coolidge’s personal and budget austerity; Herbert Hoover’s engineering background and humanitarian impulses; FDR’s longheaded concern for future generations; and John F. Kennedy’s “idealism without illusions.” His altruistic post-presidency was rivaled only by that of John Quincy Adams — another one-term president — who worked against slavery when he was elected to the House of Representatives after leaving office.

Carter’s favorite president was Harry Truman, who was also unpopular in office but grew in stature over time. He placed Truman’s famous sign, “The Buck Stops Here,” on his desk in the Oval Office and took the idea of accountability so seriously that, when running for reelection, he gave himself poor to middling grades on national television.

Like Truman, Carter believed his Baptist faith required a strict separation of church and state. He rarely spoke of his devout beliefs — even to aides — and made a point of not allowing prayer breakfasts or other religious events at the White House. But he occasionally talked to world leaders in private about religious freedom (a conversation with Deng Xiaoping helped spread Christianity to millions in China), and he infused his politics with what one of his speechwriters called a “moral ideology.” He thought US control of the Panama Canal a moral injustice to Panamanians; wasteful water projects a moral offense against fiscal responsibility; environmental degradation a moral betrayal of the planet; and war — anywhere — a moral assault on the deepest human values.

Carter’s high moral purpose sometimes made him look sanctimonious, especially to skeptics who failed to notice there wasn’t enough hypocrisy to bolster the indictment. The critics didn’t know yet that there was little to hide. But if his integrity and values were authentic, the gap between the public and private man could be wide.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, his national security adviser, was hardly the only one to notice that Carter had “three smiles”: the radiant, toothy, and sometimes contrived grin that delighted crowds and cartoonists; the tight-lipped rictus when he was angry but didn’t want to show it; and the relaxed and welcome smile he flashed in private when he found something funny or got off a dry, biting line.

The striking blue eyes told a similar story: loving or contemptuous, soulful or stern. When he was governor and president, the easiest way to get a glare from Carter’s icy blues was to move from the merits of a decision to the politics of it. He drew a bright line between campaigning—which he did for governor in 1970 and president in 1976 with a canny grasp of all the angles—and governing, where his high-minded disdain for politics exasperated other politicians and came off as naive.

Carter’s 1980 defeat had many causes — the divisive Kennedy challenge in the Democratic primaries; the prolonged captivity of the hostages in Iran; the wretched state of the American economy — but Carter’s nature played a role. He seemed as if he were carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders — never a good look. And while he had millions of admirers who liked his Everyman qualities, his modesty stripped him of the aura enjoyed and exploited by other leaders.

Unlike most who reach the summit, Carter did not always possess what soldiers call “command presence.” He could bark out orders but lacked an intangible quality that makes people want to charge up the hill behind. This made him an unusual historical specimen: a visionary who was not a natural leader.

Rosalynn, his full partner and closest adviser, thought he was a leader of a different kind. “A leader can lead people where they want to go,” she said in 2015. “A great leader leads people where they ought to go.” Her husband was not a great leader—no historians consider him in the first rank of American presidents—but Carter was a surprisingly significant one, a man who lived the advice of the columnist Walter Lippmann to “plant trees we will never get to sit under.”

The planting began in a distant America, setting on the horizon, where a real-life Huck Finn launched his own restless adventure.