Vladimir Putin and his clique ruthlessly took over Russia’s assets and used their billions to undermine Western institutions and democracies.

-

Spring 2022

Volume67Issue2

Editor’s Note: Catherine Belton is a London-based correspondent for Reuters who was Moscow correspondent for the Financial Times from 2007 to 2013. Her remarkable book, Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took on the West, chronicles the rise to power of Putin’s KGB cohort and how they enriched themselves in the capitalism of contemporary Russia. It describes how the hurried transfer of power from Yeltsin to Putin enabled the rise of a “deep state” of KGB security men that had always lurked in the background during the Yeltsin years, but now emerged to monopolize power – and endanger the West. Putin’s People was named book of the year by The Economist, Financial Times, New Statesman and The Telegraph. The following was adapted from the book with permission.

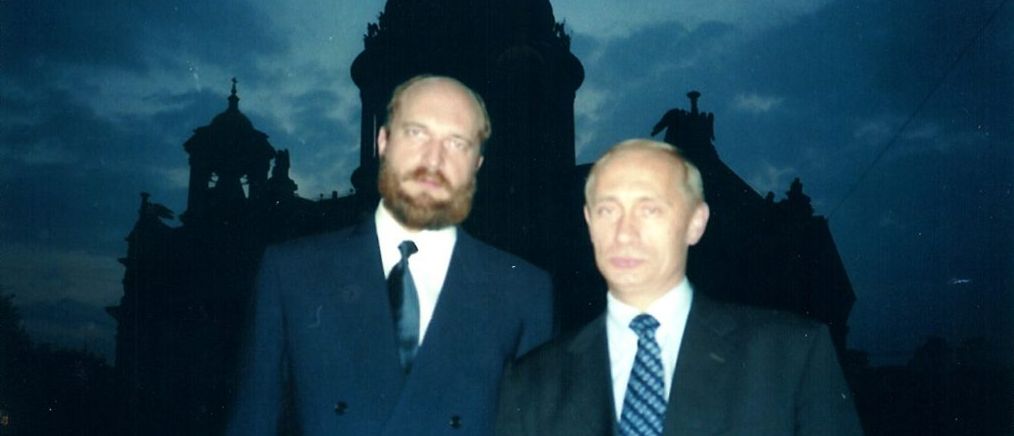

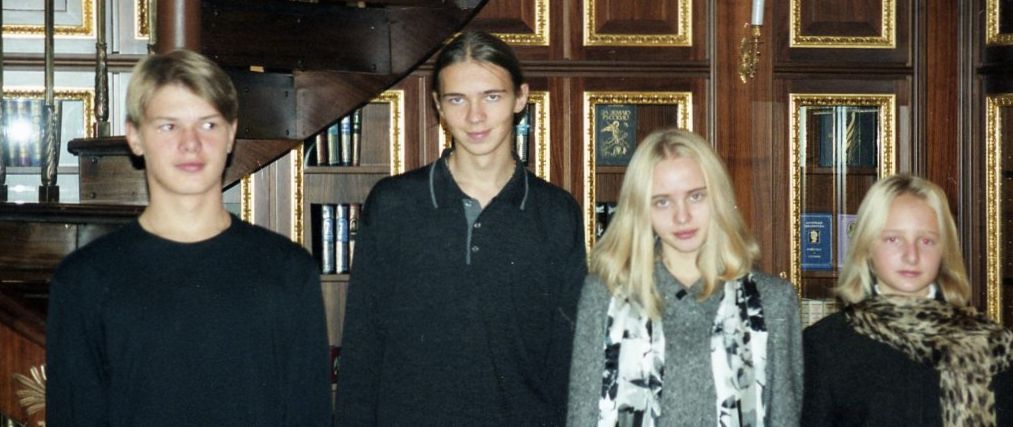

It was late in the evening in May 2015, and Sergei Pugachev was flicking through an old family photo album he’d found from 13 years ago or more. In one picture from a birthday party at his Moscow dacha, his son Viktor keeps his eyes downcast as one of Vladimir Putin’s daughter’s smiles and whispers in his ear. In another, Viktor and his other son, Alexander, are posing on a staircase in the Kremlin presidential library with Putin’s two daughters.

We were sitting in the kitchen of Pugachev’s latest residence, a three-story townhouse in well-heeled Chelsea, southwest London. The late-evening light glanced in through the cathedral-sized windows and birds chirped in the trees outside. The high-powered life Pugachev had once enjoyed in Moscow — the secret deal-making, the “understandings” between friends in the Kremlin corridors of power — seemed a world away. But Moscow’s influence was still lurking like a shadow outside his door.

The day before, Pugachev had been forced to seek the protection of the UK counter-terrorism police. His bodyguards had found suspicious-looking boxes with protruding wires taped underneath his Rolls-Royce (later found to be tracking devices), as well as on the car used to transport his three youngest children to school.

Now, on the wall of the Pugachevs’ sitting room, behind the rocking horse and across from the family portraits, the SO15 counter-terrorism command had installed a grey box containing an alarm that could be activated in the event of attack.

Fifteen years before, Pugachev had been a Kremlin insider who’d maneuvered endlessly behind the scenes to help bring Vladimir Putin to power. Once known as the Kremlin’s banker, he’d been a master of the backroom deals, the sleights of hand that governed the country then. For years he’d seemed untouchable, a member of an inner circle at the pinnacle of power that had made and bent the rules to suit themselves, with law enforcement, the courts, and even elections subverted for their needs.

But now the Kremlin machine he’d once been part of had turned against him. The tall, Russian Orthodox believer with a dark beard and a gregarious grin had become the latest victim of Putin’s relentlessly expanding reach. First, the Kremlin had moved in on his business empire, taking it for itself. Pugachev had left Russia, first for France and then for England as the Kremlin launched its attack. Putin’s men had taken the hotel project the president had granted him on Red Square, a stone’s throw from the Kremlin, without any compensation at all.

Then his shipyards, two of the biggest in Russia, valued at $3.5 billion, were acquired by one of Putin’s closest allies, Igor Sechin, for a fraction of that sum. Then his coal project, the world’s biggest coking-coal deposit in the Siberian region of Tuva, valued at $4 billion, was taken by a close associate of Ramzan Kadyrov, the strongman Chechen president, for $150 million.

It was a typical story for a Kremlin machine that had become relentless in its reach. First, it had gone after political enemies. But now it was starting to turn on Putin’s onetime allies. Pugachev was the first of the inner circle to fall. And now the Kremlin had expanded its campaign against him from the brutal closed-door courts of Moscow to the veneer of respectability of London’s High Court. There, it obtained a freezing order against his assets with ease, tying the tycoon up in knots in the courtroom along the way.

And so one day in June 2015, a few weeks after we’d met in his Chelsea home, Pugachev was suddenly no longer in the UK. His phones had all been switched off, ditched by the wayside as he ran. He’d ignored the court orders forbidding him to leave the country. He hadn’t even told his partner and mother of his three children, the London socialite Alexandra Tolstoy, who was left waiting late into the night for him to appear at her father’s 80th birthday party. He’d fled to the relative safety of his villa high in the hills above the bay of Nice, a fortress surrounded by a high iron fence with a team of bodyguards and security cameras at every turn.

Before things had got tough in London, Pugachev had never given an interview on the record in his life. Few knew who he was. Now he was speaking out. He and other inner-circle sources I interviewed laid bare how Putin came to power 20 years ago and the rise of the tight-knit clan of KGB men surrounding him. First they enriched themselves and then they began to pose a threat to the West. And there is no sign of it stopping: Putin set in motion constitutional changes that will enable him to stay in power until 2036 — an autocrat in all but name.

“These people, they are mutants,” said Pugachev. “They are a mixture of Homo sovieticus with the wild capitalists of the past 20 years. They have stolen so much to fill their pockets. All their families live somewhere in London.”

Alexander Lebedev, the former KGB officer and banker who’d positioned himself as a champion of the free press in Russia, had acquired London’s most-read and influential daily, the Evening Standard, becoming a fixture at the capital’s soirées and on the lists for the most sought-after dinner invitations.

Another was Dmitry Firtash, a Ukrainian tycoon who’d become the Kremlin’s gas trader of choice, and who, despite his links to a major Russian mobster wanted by the FBI, Semyon Mogilevich, had become a billionaire donor to Cambridge University. His chief London minion, Robert Shetler-Jones, had donated millions of pounds to the Tories, while influential party grandees served on the board of Firtash’s British Ukrainian Society.

In September 2014, we had been sitting in Pugachev’s office in Knightsbridge, a central London playground for Russia’s rich, when Pugachev said he wished he’d never rented an office there. “It’s disgusting,” he declared. The concentration of Russian cash in the square mile around him was a bitter reminder of how deep Russia’s reach into the London elite had become.

The power of the Russian cash that had poured into Europe over the past decade was also becoming visible in the rifts between European Union countries over how far economic sanctions, imposed against Russia after its invasion of Crimea, should go. In the UK, a Foreign Office official was photographed with a briefing paper arguing that Britain must not “close London’s financial centre to Russians.”

For Pugachev, the danger was clear. The system of black cash to corrupt and buy off officials had extended to all the Russian billionaires who acted as fronts at the Kremlin’s command. “They all get calls to send money for this and for that. They all say, ‘We’ll give it. What else do you need?’ This is the system. It all depends on the first person, because he has unlimited power.”

The kleptocracy of the Putin era was aimed at something more than just filling the pockets of the president’s friends. What emerged as a result of the KGB takeover of the economy – and the country’s political and legal system – was a regime in which the billions of dollars at Putin’s cronies’ disposal were to be actively used to undermine and corrupt the institutions and democracies of the West. The KGB playbook of the Cold War era, when the Soviet Union deployed ‘active measures’ to sow division and discord in the West, to fund allied political parties and undermine its ‘imperial’ foe, has now been fully reactivated.

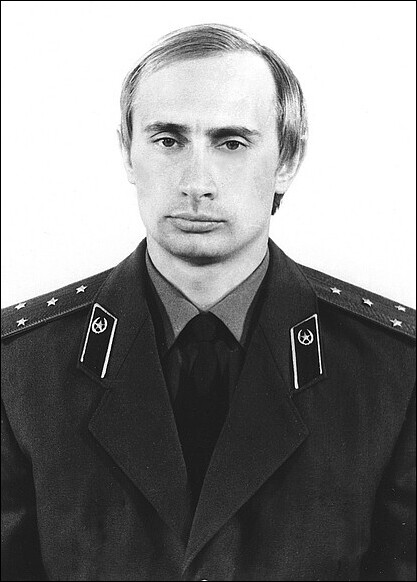

What’s different now is that these tactics are funded by a much deeper well of cash, by a Kremlin that has become adept in the ways of the markets and has sunk its tentacles deep into the institutions of the West. Parts of the KGB, Putin among them, have embraced capitalism as a tool for getting even with the West. It was a process that began long before, in the years before the Soviet collapse. Putin’s takeover of strategic cash flows was always about more than taking control of the country’s economy. For the Putin regime, wealth was less about the well-being of Russia’s citizens than about the projection of power, about reasserting the country’s position on the world stage.

The system Putin’s men created was a hybrid KGB capitalism that sought to accumulate cash to buy off and corrupt officials in the West, whose politicians, complacent after the end of the Cold War, had long forgotten about the Soviet tactics of the not-too-distant past. Western markets embraced the new wealth coming from Russia, and paid little heed to the criminal and KGB forces behind it. The KGB had forged an alliance with Russian organized crime long ago, on the eve of the Soviet collapse, when billions of dollars’ worth of precious metals, oil and other commodities was transferred from the state to firms linked to the KGB.

From the start, foreign-intelligence operatives of the KGB sought to accumulate black cash to maintain and preserve influence networks long thought demolished by the Soviet collapse. For a time under Yeltsin the forces of the KGB stayed hidden in the background. But when Putin rose to power, the alliance between the KGB and organized crime emerged and bared its teeth.

For Pugachev, his maneuvering to help propel Putin to power is now a constant source of remorse and regret. “I’ve learned an important lesson,” he said when we talked at his home in France. “And that is: power is sacred. We all thought the people weren’t ready [for full democracy], and we would install Putin . . . Of course, we thought it was cool. We thought we’d saved the country from the communists.”

In the rush to help install Putin, Pugachev had ignored warnings that appointing someone from the KGB was “to enter a vicious circle.”

Those who believed they were working to introduce a free market and democracy had underestimated the enduring power of the security men.

“This is the tragedy of Russia,” said Pugachev.