Why can't the U.S. Senate be more like it was in the 1960s, when members of “the world’s greatest deliberative body” put the interests of the country first?

Editor's Notes: The author of this editorial, Ira Shapiro, is a former Senate staffer who has written three books about the Senate: The Last Great Senate: Courage and Statesmanship in Times of Crisis (2012); Broken: Can the Senate Save Itself and the Country? (2018); and The Betrayal: How Mitch McConnell and the Senate Republicans Abandoned America (2022). This essay includes some text included in Mr. Shapiro’s books, with the permission of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers’ Inc.. Mr. Shapiro’s speeches and articles about the Senate can be found on his website, www.irashapiroauthor.com.

In the American constitutional system, no one person – not even the president – is supposed to be able to undermine our institutions and jeopardize our democracy. The framers of the Constitution wanted a strong central government because the weakness of the Articles of Confederation had quickly revealed the limits of what the states could accomplish on their own. But having fought the American Revolution to free the colonies from Great Britain and its monarch, our founders feared the possibility of an overreaching executive who would seek to become a king or an autocrat. They also feared a president who might be corrupt, pursuing personal gain instead of the national interest, and that he could be susceptible to powerful foreign influences.

Consequently, the founders designed a system of checks and balances, the most distinctive feature of which was the Senate. They made it the strongest upper house in the world, with the power to “advise and consent” on executive and judicial nominations, to ratify treaties, and to hold impeachment trials.

Robert C. Byrd, the longest serving senator and its most dedicated historian, who understood the Senate’s potential and hated when it failed to reach that mark, wrote that “the American Senate was the premier spark of brilliance that emerged from the collective intellect of the Constitution’s framers.”

James Madison, characteristically, cut to the heart of things in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1787. He called the Senate “the great anchor of the government…Such an institution may be sometimes necessary as a defense to the people against their own temporary errors and delusions.”

The Senate would be assigned many functions, but it had one fundamental, overriding responsibility: to be a bulwark against any leader who would abuse the powers of the presidency in ways that threatened our democracy. Some 230 years later, when just such a president finally reached the White House, the Senate should have been democracy’s strongest line of defense.

Instead, a nightmare scenario happened: the Senate, weakened from a long period of accelerating decline, riven by hyper-partisanship, and led by a paper-thin Republican majority, proved incapable of checking Trump’s authoritarian desires. Sometimes, the Senate aided and abetted Trump; other times, it simply stood by and allowed him to rampage unchecked. Any fair historical assessment will blame the Senate for its dereliction of duty – a failure to prevent President Trump’s assault on our democracy as he worked to prevent the peaceful transfer of power after losing the 2020 election to Joe Biden.

See also “Sometimes Our Job is to Say ’No’” by Sen. Jesse Helms in the December 1998 American Heritage

It is impossible to understand the decay of our politics and the breakdown of our government, even before Trump’s presidency. without recognizing that the Senate was ground zero for America’s political dysfunction; it is the political institution that failed the country the longest and the worst. The Senate’s failure was particularly crippling because it was supposed to be not only a check on a rogue president, but the balance wheel and moderating force in our political system – the place where the two parties come together to find common ground through vigorous debate and principled compromise to advance the national interest.

But to perform its role as what Walter F. Mondale once called “the nation’s mediator,” the Senate required a degree of bipartisan comity that has long been lost. Without that bipartisan comity, the Senate not only reflects the polarization in the country; it exacerbates it by demonstrating it constantly at the highest and most visible level of government.

The Senate’s failure was particularly painful to a generation that remembers the Senate at its best. America went through a searing period of constitutional crisis from 1967 to 1974 as the fierce debate over our involvement in Vietnam and the pace of racial progress produced violence in the streets, the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and ultimately President Richard Nixon’s abuses of power generically known as “Watergate.” But in that turbulent period, the Senate occupied a special place in America. Working with presidents where possible and holding them accountable when necessary, the Senate provided ballast, gravitas, and bipartisanship leadership during those crisis years for our country.

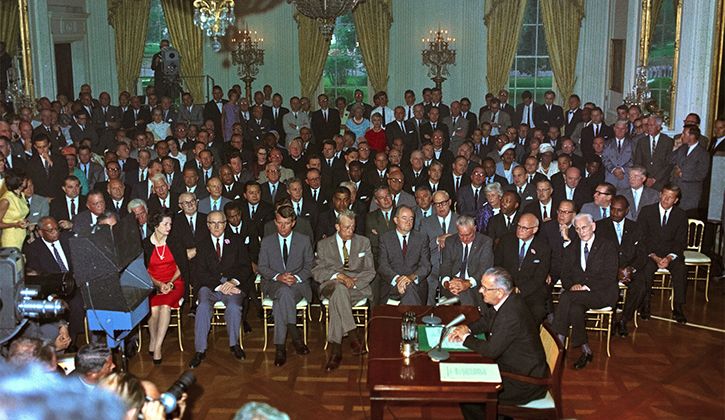

That Senate overcame our country’s legacy of racism to by enacting the Civil Rights Act of 1964, probably the most consequential legislative accomplishment in American history, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It attacked the premises of the Vietnam War, produced the Democratic challenges to President Lyndon Johnson, and ultimately, on a bipartisan basis, cut off funding for the war. The Senate battled Nixon’s efforts to the turn the Supreme Court to right, defeating two of his nominees in two years.

Through a summer of memorable televised hearings, the Senate made Watergate understandable to the nation and held Nixon accountable. It conducted an extraordinary investigation into the abuses of the intelligence agencies and spearheaded new environmental and consumer protections and expanded food stamps and nutrition programs, as well as civil rights for minorities and women. And after Nixon resigned and the Vietnam War ended, the Senate kept on producing major accomplishments for the country: putting in place a new energy policy; preserving the beauty of Alaska lands; and saving Chrysler Corporation and New York City from bankruptcy.

In Washington, D.C., and across our country, millions of Americans who were first drawn to politics because of John F. Kennedy, civil rights, or the Vietnam War remember the age when the Senate was great – the Senate of Democrats Hubert Humphrey, Ted Kennedy, Philip Hart, Edmund Muskie, Henry “Scoop” Jackson, Gaylord Nelson, Frank Church, Sam Ervin, Robert Byrd, Birch Bayh and Eugene McCarthy and Republicans Everett Dirksen, Howard Baker, Bob Dole, Jacob Javits, Margaret Chase Smith, John Sherman Cooper, Ed Brooke, Barry Goldwater, and countless other formidable legislators, whose names still resonate in Washington and in their states.

The Great Senate was hardly perfect. The Senate gave President Lyndon B. Johnson the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in August 1964 because the Democrats wanted him to look strong against Barry Goldwater in the presidential campaign, and watched in horror as he used it as license to escalate the U.S. commitment to Vietnam from sixteen thousand troops to more than half a million.

But the Senate of that era remained powerful and consequential despite its lapses. Dealing with civil rights, war and peace, and presidential power, the Senate seemed to have a special relationship to the Constitution. It had moral authority. It occupied a unique role in our country, just as the Founders had intended.

Around the world, there is no “upper house” comparable to the U.S. Senate. In other democracies, the “upper house” is either honorific, like the British House of Lords, or involved in legislation, but with constrained powers, like the upper house of the Japanese Diet. For that reason, the U.S. Senate became routinely known as the world’s “great deliberative body” (although not in recent decades.)

Despite the accolades, the painful truth is that the Senate failed to measure up to the challenges of the times for long periods of American history. In his 2005 book, The Most Exclusive Club: A History of the Modern United States Senate, political historian Lewis L. Gould reached a depressing conclusion: “For protracted periods – at the start of the twentieth century in the era of Theodore Roosevelt, during the 1920’s, and again for domestic issues in the post-World War II era – the Senate functioned not only as a source of conservative reflections on the direction of society but as a force to genuinely impede the nation’s vitality and evolution.”

The Senate of the 1960’s and 1970’s stands as an extraordinary exception to Gould’s gloomy analysis. For a period of nearly twenty years, the Senate came closer to the ideal set forth by the Founding Fathers than at any time in our nation’s history. Men – and the Senate was at that time comprised of all men, other than Margaret Chase Smith, who was an independent stalwart for most of the period, and Nancy Kassebaum, who arrived in 1979 – of intelligence, experience, and genuine wisdom came together to help steer the ship of state during a perilous period.

What made that Senate great?

It started with a unique group of people at a unique time in American history. Tom Brokaw’s Greatest Generation needs no postscript. But it is certainly true that the experience that many members of the Great Senate shared by serving in World War II profoundly influenced their lives and shaped their public service. Men who fought at Normandy or Iwo Jima or the Battle of the Bulge weren’t frightened by the need to cast a hard vote now and then. Seeing Robert Dole or Daniel Inouye or Paul Douglas on the Senate floor, living with crippling injuries or pain, and other veterans fortunate enough to escape unscathed, set a standard of courage and character for those who followed them.

Those men returned from the war with confidence in themselves and their country. They became party builders. They believed in what America could accomplish, and most of them believed strongly that government had an indispensable role to play. Having seen America’s strength, they were also willing to confront, and rectify, its weaknesses. They also got to serve at a time when America’s economic prosperity was unquestioned, and its potential seemed unlimited. That allowed for ambitious legislative efforts to build the nation, expand opportunities, and right historic wrongs.

The Great Senate was also a magnet that drew talented, ambitious young men and women from all over the country, regardless of whether their fathers or mothers had been famous or obscure. They first flocked to Washington in the early to middle 1960’s, attracted by the idealism and excitement of John Kennedy’s presidency. Later, they came because of their commitment to civil rights, opposition to the war in Vietnam, or anger over Watergate. The Senate was the place to be: where a young man or woman could hitch their star to a major national figure, make a mark at a young age, and learn first hand the skills needed to accomplish things in politics – above all, when to stand on principle, and when to compromise for the greater good.

It was no accident that the staff of the Great Senate included young men and women who would be future senators, congressional leaders, and Cabinet members: George Mitchell, Tom Daschle, Susan Collins, Mitch McConnell, Lamar Alexander, Fred Thompson, Chris Van Hollen, Leon Panetta, Tom Foley, Jane Harman, and Norm Dicks; future press and media luminaries: Tim Russert, Chris Matthews, George Will, Lawrence O’Donnell, Mark Shields, Jeff Greenfield, Colbert King, and Steven Pearlstein; and a future Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright; two Supreme Court justices, Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan, and one President: Bill Clinton. They trained in the right place.

As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once wrote about those who had been young during the Civil War: “In [their] youth, to [their] great good fortune, [their] hearts were touched by fire.”

But it was not just the unique senators and staff members, nor the crisis times they faced, that made the Senate great. It was a concept of the Senate that they shared.

Senators take the oath of office to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.” But there was also an unspoken oath that many senators came to understand. The people of their states had given the incredible privilege and honor of being United States senators. They had received the most venerable of titles that a republic can bestow and a six-year term (usually leading to multiple terms) to serve. They would have the opportunity to deal with the full spectrum of issues, domestic policy and national security, and they would develop expertise and experience valuable to the Senate and the country. In exchange, when they sorted out the competing pressures on them, they would serve their states and would not forget their party allegiance, but the national interest would come first. They would bring wisdom and independent judgment to bear to determine what was best for the national interest.

And part of the unspoken oath was an obligation to make the Senate work. As Mike Mansfield, the longest serving Senate majority leader in history memorably noted: “In the end, it is not the individuals of the Senate who are important. It is the institution of the Senate. It is the Senate itself as one of the rocks of the Republic.” The Senate was an institution that the nation counted on to take collective action. Understanding that brought about a commitment to passionate, but not unlimited, debate; tolerance of opposing views; principled compromise; and senators’ willingness to end debate, and vote up or down, even if it sometimes meant losing.

Those qualities characterized the great Senate and its members. The great liberal Democrat Hubert Humphrey and the great conservative Republican Barry Goldwater were poles apart politically, but no one doubted that they were both committed to the national interest and to the Senate as an institution. Because of those overriding commitments, the senators of the 1960’s and 1970’s competed and clashed, cooperated and compromised, and then went out to dinner.

The Great Senate worked on the basis of mutual respect, tolerance of opposing views, and openness to persuasion in the search for bipartisan solutions. The Senate has often been described as a club, but at its best, the Senate actually functioned more like a great team, in which talented individuals stepped up and did great things at crucial moments, sometimes quite unexpectedly.

The commitment to pursing the national interest and making the Senate work acted as powerful constraints on partisanship. During most of the 1960’s and 1970’s, the Senate, although a political institution, was surprisingly free from partisanship. The herculean effort to give civil rights to black Americans, the tragedy of Vietnam, the crisis of Watergate, checking the imperial presidencies of Johnson and Nixon — these were not partisan issues, and the Senate responded in a bipartisan way. To meet every key challenge, a Democrat and a Republican would lead together: Hubert Humphrey and Everett Dirksen breaking the Southern filibuster on the Civil Rights Act; Frank Church and John Sherman Cooper and George McGovern and Mark Hatfield to cut off funding for the Vietnam War; Sam Ervin and Howard Baker exposing the Watergate coverup.

The Senate of that era was a healthy ecosystem, in which trust, among senators and staff, was the coin of the realm. To a greater degree than is usually recognized, the Senate reflected the unique leadership of Mansfield. Mansfield, born in 1900, a professor of Asian history and a World War I veteran who served in all three branches of the military, was an unlikely politician: laconic, intellectual, and averse to self-promotion. He didn’t seek to be a Senate leader, accepting the job very reluctantly at the request of his close friend, President-elect John F. Kennedy. He failed to inspire confidence initially, to the point that he offered the Senate his resignation near the end of his third year if it was unsatisfied with his light-touch approach to leadership. “It is unlikely that [Mansfield] twisted one arm in his sixteen years in charge,” Tom Daschle and Trent Lott, Senate leaders between 1996 and 2004, would later write in admiration and amazement. In a period of agony for our nation, after the assassination of President Kennedy, Mansfield built a Senate based on trust and mutual respect, enabling the body to meet the challenges of a turbulent period in a bipartisan way.

Universally admired for his wisdom, honesty, and fairness, Mansfield worked with President Johnson and the Senate led by Hubert Humphrey and Everett Dirksen to break the Southern filibuster to pass the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964. Drawing on his deep knowledge of Asia, Mansfield presciently warned Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon that the U.S. engagement in Vietnam was disastrous. Under his leadership, the Senate became the forum for challenging, and ultimately ending, the war.

In October 1972, when Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered the abuses of Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign, Mansfield immediately promised a full and fair Senate investigation. When the Senate convened in January 1973, it unanimously voted to create a select committee to investigate the abuses, by then known as “Watergate,” even though Nixon had won reelection in a 49-state landslide. The bombshell revelations of the committee’s memorable hearings in the summer of 1973, led by Democrat Sam Ervin and Republican Howard Baker, paved the way inexorably to Nixon’s resignation a year later.

Although Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory in 1980 shattered the great Senate of the 1960’s and 1970’s, producing the first Republican majority Senate since 1955, the Senate, under the leadership of Howard Baker and then Bob Dole, even though more conservative, continued to produce bipartisan legislative accomplishments through the 1980’s, such as shoring up the Social Security system; a major revision of the federal tax code; reorganization of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; comprehensive immigration reform; creating a balance between research pharmaceutical companies and the generics; the landmark legislation to improve the lives of Americans with disabilities.

The Senate’s long decline started more than thirty years ago. To a large extent, the decline reflected the Senate’s inability to overcome the centrifugal forces of our politics as the two parties grew further apart, aligning on regional, racial, and ideological lines. The trust, mutual respect, and bipartisanship that had characterized the Senate of the 1960’s and 1970’s, which had carried over through 1980’s, vanished as the partisan divide became a chasm.

The rise of Newt Gingrich and the advent of 24/7 cable news combined to make our politics much harsher. The Senate, which had been almost a demilitarized zone where partisanship was concerned, became just another part of the “permanent campaign.” Compromise, the sine qua non of politics, became almost a dirty word. Moderates became fewer, and almost an endangered class; a record number of senators (14), including some of the most respected dealmakers on both sides of the aisle, chose to retire in 1996. Their farewell speeches, expressing despair about the Senate’s paralysis and the loss of civility in our politics, sound like they could be delivered today.

The Senate, whose wisdom the nation relied on in times of crisis, produced the disgraceful confirmation hearings in which Senate Republicans (and Joe Biden, the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee) brutalized Professor Anita Hill over her allegations that Judge Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her. A decade later, the Senate approved the exorbitant tax cuts proposed by President George W. Bush and rushed to judgment to give Bush the authority to invade Iraq. Robert Byrd, the keeper of the Senate flame, ripped the “supine Senate” for allowing Bush to intrude on Congress’ authority to declare war and appropriate funds. In 2005, political historian Lewis L. Gould wrote that “a profound sense of crisis now surrounds the Senate and its members.”

The historic election of Barack Obama, coming to office at a time of absolute economic crisis, should have triggered a Senate comeback – if not to greatness, then at least to respectability. Astonishingly, exactly the opposite happened. Even a national economic emergency – 750,000 jobs disappearing in January 2009 – was not enough to produce even a trace of bipartisan cooperation. Mitch McConnell united his Republican caucus in opposition to Obama’s efforts to avert a second Great Depression, almost preventing the passage of the economic stimulus legislation desperately needed to restart the economy. McConnell then led his caucus in scorched earth opposition to the Affordable Care Act, which triggered the rise of the Tea Party, and the Dodd-Frank legislation to strengthen regulation to prevent another meltdown of the financial system.

Overcoming the opposition, Obama and the Democrats enacted three momentous pieces of legislation, yet the Senate was universally regarded as dysfunctional. Carl Levin, then a thirty-two-year Senate veteran, was struck by the paradox. “It’s been the most productive Senate since I’ve been here I terms of major accomplishments,” Levin observed, “and by far the most frustrating. It’s almost impossible day to day to get anything done. Routine bills and nominations get bottled up indefinitely. Everything is stopped by the threat of filibusters – not real filibusters, just the threat of filibusters.”

In a widely read New Yorker article titled “The Empty Chamber,” George Packer wrote: “The two lasting legislative achievements of the Senate, financial regulation and health care, required a year and a half of legislative warfare that nearly destroyed the body.” The battles took their toll on Obama’s political standing, but also on that of Congress. In March 2009, 50% of Americans expressed a favorable opinion of Congress. In March 2010, it was 26%.

Obama had won the legislative fights, but McConnell and the Republicans would claim the political victory. In the 2010 elections, the Democrat suffered major losses across the country. Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa – all states that Obama carried in 2008 – would now be controlled by Republican governors and state legislators. The Republicans gained sixty-three seats to capture a majority in the House, and picked up six Senate seats, which put them in striking distance of a majority in the Senate.

Jonathan Alter would write: “Less than two years after arriving in Washington as a historic figure heralding a new era, Barack Obama was a wounded president fighting for his political life.” Obama would recover enough to win re-election, but it is fair to say that the bitter anger that propelled Donald Trump to the presidency originated in the Tea Party rage and the Senate obstruction of 2009-2010.

The degraded Senate which opened the door to Donald Trump then failed to protect the nation from him. The Senate Republicans didn’t fail because they were incompetent, nor because they missed the danger signs. Many Republicans, along with all the Democrats, knew that Trump was dangerous; indeed, many saw him as a witting or unwitting agent of Vladimir Putin.

The Senate failed because its Republican members abandoned the late Senator John McCain’s guiding principle: “Country first.” When it mattered most, the Republican senators put their personal political interests first, the Republican Party’s interests second; and the country’s interests nowhere. As America faced unprecedented, cascading, intersecting crises, the Republican senators chose to stand with Trump, either actively supporting him or silently acquiescing. Some undoubtedly convinced themselves that Trump would wither away or that they would find an exit ramp. But as George Ball, the State Department official who famously dissented from the escalation of the Vietnam War, grimly warned: “He who rides the tiger cannot choose where he dismounts.”

There is a familiar Sicilian proverb: “A fish rots from the head.” The story of the Senate’s rot in the past fifteen years is first and foremost the story of Mitch McConnell. He was an unyielding obstructionist during the Obama presidency, culminating in his refusal to hold a vote of Obama’s Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland following the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February 2016.

With Trump in the White House, McConnell became a relentless battering ramp, riding roughshod over one Senate custom and norm after another. After Trump shocked the world by winning the presidency, America urgently needed a strong Senate, with a leader in mold of Democrat Mike Mansfield or Republican Howard Baker, politicians who are rightly remembered as great statesmen and patriots. Instead, America got McConnell, a superb political strategist and tactician who was extraordinarily effective in achieving his partisan objectives, at great cost to the Senate and the country that depended on it.

Of course, even McConnell, the most powerful Senate leader in history, could not have done what he did without his troops. Throughout the Trump presidency, McConnell had only a very narrow majority with which to work. At any moment, three or four Republicans could have stopped him in his tracks. This happened exactly once, in July 2017, when John McCain, dying of brain cancer, memorably joined Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski in defeating McConnell’s brazen attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act without hearings, committee action, or floor debate.

Just as McConnell enabled Trump, the other Senate Republicans enabled McConnell. Except for Mitt Romney, who cast the only Republican vote to remove Trump from office in the first impeachment trial, all the Republican senators were complicit. The shameless Lindsey Graham, who had been John McCain’s best friend and Donald Trump’s most scathing critic, spun 180 degrees to become Trump’s favorite golf partner and McConnell’s wing man. Less verbose and simply shameful, Lamar Alexander and Rob Portman, two once-superb public servants, allowed themselves to become virtually invisible at every moment when their voices and their stature would have been useful to call attention to Trump’s abuses of the presidential office.

In the crisis year of 2020, one of the darkest in American history, McConnell and his Republican caucus exonerated Trump after his first impeachment despite uncontroverted evidence that he withheld military assistance from Ukraine to benefit his presidential campaign by damaging Joe Biden, his strongest potential opponent. They averted their eyes as Trump lied about Covid-19, hawked fake cures for the virus, attacked blue state governors, and mocked masks and social distancing – a deluge of misinformation that caused thousands of needless deaths. They opted for silence when Trump invited his supporters to indoor rallies at the peak of the pandemic. They allowed Trump’s “Big Lie” that the election was stolen to stand unrebutted for weeks, poisoning the thinking of 70 percent of his voters – roughly 50 million Americans.

The Senate Republicans roused themselves to action only long enough to ram through the confirmation of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court eight days before Election Day. A dozen of them refused to certify the Electoral College results, providing an opportunity for the January 6 assault on the Capitol.

In the days following January 6, many Republican senators condemned Trump’s behavior, but as time went by, they did their political calculations and concluded that he remained too strong with the Republican base to bring down. On February 13, only seven of fifty Senate Republicans moved to convict Trump in his second impeachment trial. The Senate’s Republican members did not just fail; they betrayed their oaths of office, sacrificing American lives and American democracy.

America has paid a terrible price for the experiment with Trump, a narcissistic outsider and disrupter, with authoritarian impulses and contempt for our democratic institutions. But it is McConnell, the political stalwart and faux institutionalist, who poisoned and undermined our political system from within, transforming the Senate into a hyper-partisan battle zone, draining it of the trust and pride that made it work in its great days, while using it for his own purposes.

By 2022, the once admired Senate was the object of almost universal anger and contempt. Criticism focused on the Senate’s anti-democratic nature, given the requirement that every state have two senators, regardless of population, compounded by the super-majority required to enact most legislation. Despite McConnell’s entreaties, several popular, term-limited Republican governors – Chris Sununu, Doug Ducey, and Larry Hogan – declined to run for his degraded Senate. Two other promising Republicans opted for greener pastures: Mike Braun to run for governor of Indiana and Ben Sasse to become chancellor of the Florida university system. Rob Portman and Roy Blunt chose to retire. Assessing why presidential candidates no longer seemed to come from the Senate, Amy Walter, the respected author of The Cook Political Report with Amy Walter, observed: “If you’re a senator…you have the burden of being a member in the most hated institution in America.”

Yet at the same time, the Senate came through with an impressive series of bipartisan accomplishments. After enacting the infrastructure legislation in 2021, the Senate passed the CHIPS and Science Act, a $50 billion dollar commitment to the U.S. semiconductor industry. The Senate overcame the opposition of the NRA and the gun manufacturers to pass the first significant, if inadequate, piece of gun safety legislation since 1994. The Senate moved quickly to legislate protection for gay and interracial marriage, reformed the archaic Electoral Count Act to eliminate the uncertainty around the Electoral College certification, and moved to fund the government through September 2023.

These legislative successes reflected the political leadership of President Biden and Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer, but they were made possible in each case a group of Republicans, ranging from 12 to 19 joined the full Democratic caucus. In most cases, an energetic bipartisan more “gang” of bipartisan gang of eight or more senators provided the impetus for the legislation and cut the deals to make it possible.

McConnell supported every piece of bipartisan legislation except the marriage equality act, as did Lindsey Graham. Politicians operate at the intersection of conviction, calculation, and conscience, and clearly, some combination of factors caused a significant number of Republican senators to change their approach and engage constructively. None of them will ever apologize for failing the American people during the crisis time of 2020-21, but they may try to compensate by leaving a better legacy going forward. Perhaps they also decided that they did not want to spend their careers in a failed institution, which the public regards with contempt.