Many of our food-safety laws arose after healthy young volunteers became sick when they tried commercial foods containing toxic additives.

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a Contributing Editor of American Heritage who publishes a popular and respected history blog called The Attic.

The menu at a dinner table in 1900 might have looked like this:

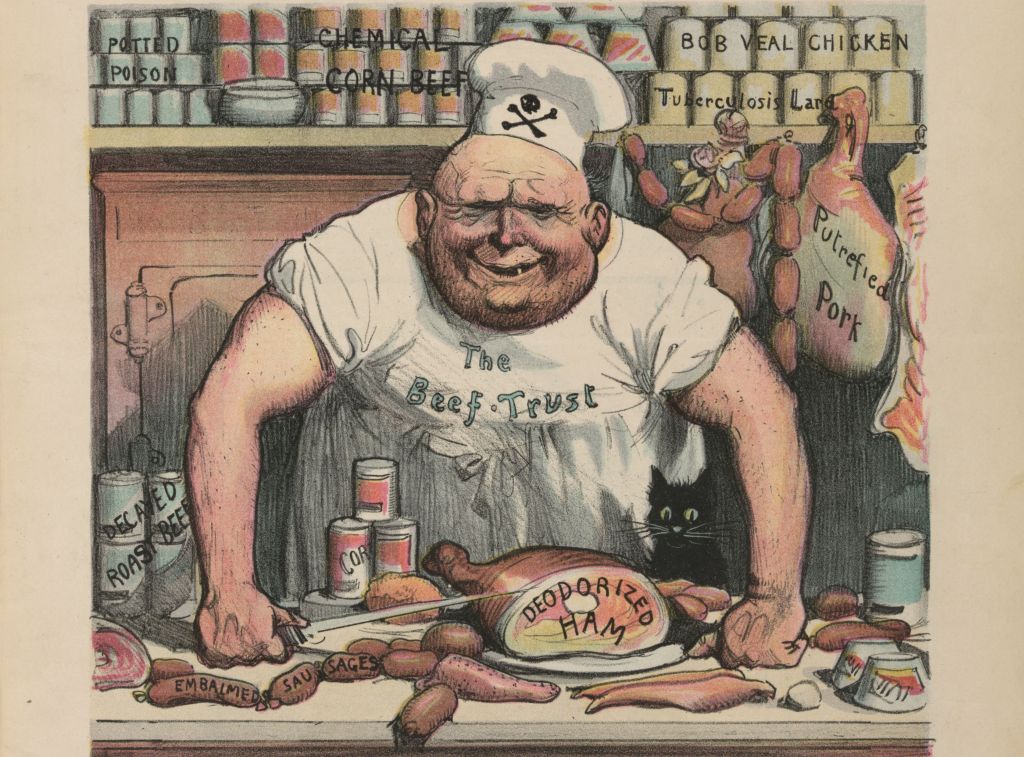

Juicy beef, flavored with borax and formaldehyde

Green peas, laced with copper sulfate

Pork and beans, with a soupçon of formaldehyde

Lemon ice cream infused with methyl alcohol

Bon appétit, America!

As Americans moved from farms to cities at the turn of the century, upstart corporations such as Nabisco, Heinz, and Campbell’s packaged food for the hungry masses.

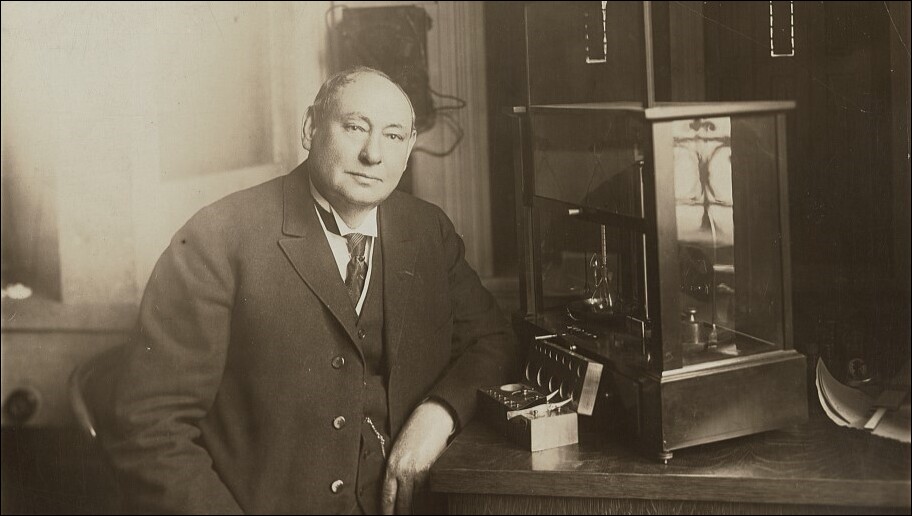

Label after label touted purity, quality, and freshness, but none listed a single ingredient. Then, in 1902, a crusading chemist named Harvey Washington Wiley created “The Poison Squad.”

Born on an Indiana farm, Wiley grew up eating food as fresh as morning. After a stint in the Civil War, he earned a medical degree, then studied chemistry at Harvard. Wiley might have remained a chemistry professor, but his studies in Germany revealed to him a new kind of lab.

Throughout Europe, where hundreds of children had died from bad milk and meat, food additives were being screened, often banned. Professor Wiley learned how to detect additives and to be suspicious. Back in Indiana, he turned his suspicion to locally made sugar, honey, and maple syrup. He was shocked.

So-called sugar was mostly corn syrup. Honey, likewise, with bits of honeycomb added. Maple syrup? Syrupy yes, but not maple.

Wiley’s early studies alarmed the budding food industry, and his character — judged “too young and too jovial” — did not fit academia. In 1882, he left Purdue for Washington, D.C to become chief chemist at the Department of Agriculture.

For the rest of the decade, he examined American food. What he found made him sick. Milk was watered down, a pint of water per quart, whitened with chalk or plaster of Paris. Vegetables were greened by copper sulfate. And almost everything contained borax, a buffering agent used in many cleaning products, including the laundry detergent booster called “20 Mule Team Borax”.

Wiley lobbied for pure food laws, but “the committee rooms of Congress,” he lamented, “are jammed with the attorneys for the industries, a formidable lobby of influential men who will stop at nothing to kill legislation.” Bills were banned, blocked, tabled. Congress slashed Wiley’s budgets. His name was slurred in industry propaganda. He approached the new century all but defeated. Then came war.

Soldiers in the Spanish-American war ate canned beef by the ton. But cans, packed with ingredients such as borax, chloroform, formaldehyde, and salicylic acid opened with a “poof!” Officers saw troops sickened by “embalmed beef.” One doctor compared its smell to that of “a dead human body.”

When word reached the public, a pure-food campaign began. Inspired, Wiley introduced another bill in 1902. It was defeated, but Congress gave him $5,000 for “Hygienic Table Studies.”

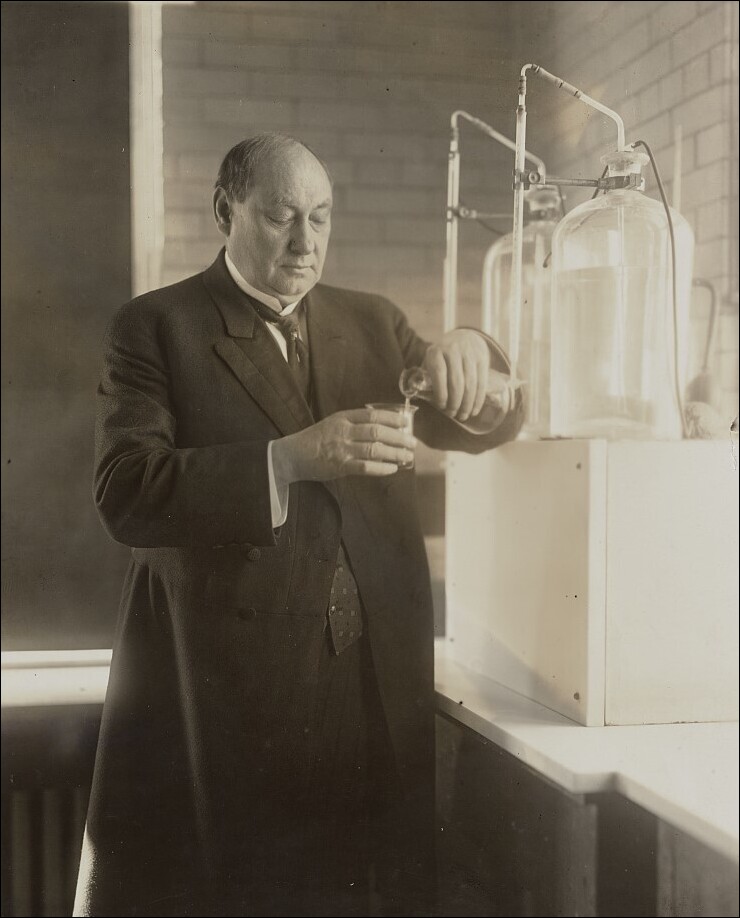

Under the cover of jargon, Wiley began recruiting human guinea pigs. Promised $5 a month plus three meals a day, hundreds lined up. Strong stomachs were needed, Wiley warned. Additives would be in each meal, and despite sickness or death, lawsuits were out of the question.

In the summer of 1902, the trials began. Outside a basement kitchen in the Agriculture building, Wiley hung a sign: “NONE BUT THE BRAVE CAN EAT THE FARE.” And, for the next year, a dozen men of “high moral character” chowed down on food laced with every common additive.

Before and after meals, each strapping man was weighed and measured. Urine, sweat, hair, and stool were analyzed.

Sworn to silence, the men ate on, but word leaked. A Washington Post reporter coined the name “the poison squad,” and the squad was soon eulogized in cartoons, poems, and songs.

to put us beneath the sod;

We’re death-immunes and we’re proud as proud--

Hooray for the Pizen Squad!

The test results were more sobering. Borax caused headaches, stomach aches, vomiting. Copper sulfate damaged livers and kidneys. The public read of strapping young men sickened, nauseated, “losing flesh.”

“One of the reasons that this issue resonated so strongly was that everybody was eating this food,” said Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation.

Wiley’s “table studies” spread the alarm. By 1904, America’s first celebrity chef, Fanny Farmer, was campaigning for pure food. The National Consumer League joined the fight. Then, in 1906, the novel The Jungle revealed the nauseating conditions in Chicago meat packing plants.

“I aimed at the public’s heart,” author Upton Sinclair said, “and by accident, I hit it in the stomach.”

Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt, who had eaten “embalmed beef” with his Rough Riders in Cuba, a Pure Food and Drug Act made its way through Congress. The bill was fiercely opposed by conservatives in the chamber, with one Southerner criticizing it as “a Trojan horse with a bellyful of inspectors and other employees.”

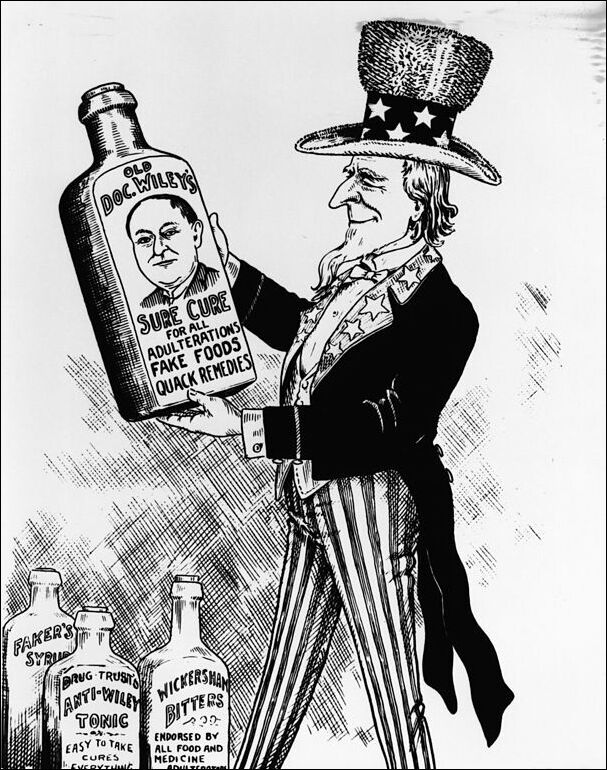

But, supported by letters from a million women, the bill passed In 1906. The so-called “Wiley Act” established the Food and Drug Administration.

Wiley and his team of chemists began banning dangerous additives. Under the Meat Inspection Act, slaughterhouses were cleaned up. Labeling laws required lists of ingredients. Wiley was a good choice to head up the new FDA. Having been born on a farm and worked with the farm industry for many years in Indiana, he understood the issues of food producers. He often stressed the importance of protecting honest businessmen. But he faced constant opposition from commercial interests, and the scope and enforcement of the law were frequently fought over.

A key target was patent medicines, which, before the Wiley Act, could contain alcohol, morphine, opium, and cannabis without labeling. One of the most famous patent medicines, Stanley’s Snake Oil, was sold by Clark Stanley, the “Rattlesnake King.” When his liniment was tested by the FDA, it was found to contain mineral oil, red pepper, turpentine, and camphor.

But sleep-deprived parents of young children complained about the FDA’s ban of Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, a popular medication for fussy babies, the primary ingredients of which were morphine and alcohol. Despite being known as the Baby- Killer syrup, the medication sold a reported million and a half bottles a year. A teaspoonful of it was equivalent to about 20 drops of laudanum, so it’s not hard to understand why so many babies who were given the drug went to sleep. Sadly, some never woke up.

Wiley had only limited success with a patent medicine marketed by a former Confederate colonel in Georgia and given the name “Coca-Cola,” which referred to two of its ingredients: cocaine and kola nuts, a source of caffeine. Of course, cocaine is gone from Coke, but its caffeine continues to give drinkers a buzz.

After years of battling corporate con men and lobbyists, Harvey Wiley took over the lab of Good Housekeeping Magazine, where he continued his work on behalf of the public. He published a number of books, and died in 1930, on the 24th anniversary of the Wiley Act.

The men of Wiley’s original Poison Squad recovered their health. No one knows what happened to them, but we thank them for their service. In the new century, the worst of the additives that Americans had once devoured found other uses. Borax became a laundry agent, copper sulfate a pesticide. Formaldehyde returned to labs.

“The Poison Squad,” historian Deborah Blum noted, “was one of the most significant experiments in the 20th century.” But Harvey Wiley offered a more poetic assessment that remains, alas, true.

We sit at a table delightfully spread

And teeming with good things to eat

And daintily finger the cream-tinted bread,

Just needing to make it complete.

A film of the butter so yellow and sweet,

Well suited to make every minute

A dream of delight. And yet, while we eat,

We cannot help asking, “What’s in it?”