Frederick Olmsted pioneered landscape architecture, designing Central Park and nearly a hundred other parks and campuses across the U.S. and Canada.

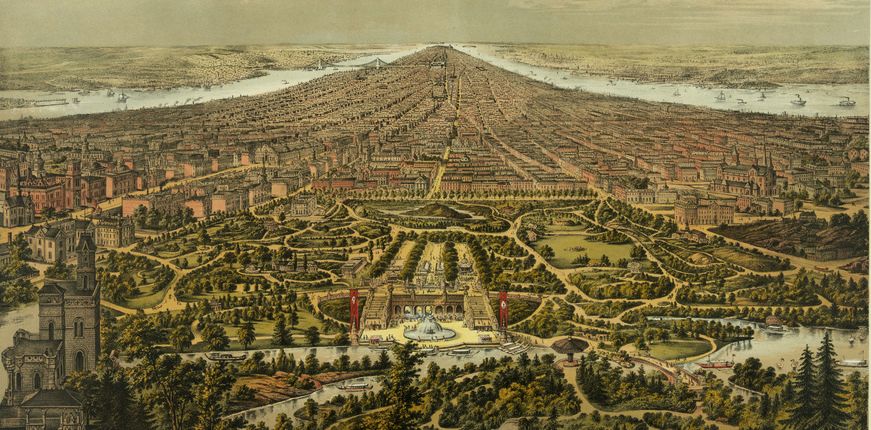

On March 25, 1893, a gala dinner was held in honor of Daniel Burnham, the driving force behind the Columbian Exposition, a World’s Fair about to open in Chicago. Various artists and architects who had worked on the project gathered for this lavish event.

But when Burnham took the stage to be feted, he chose to deflect credit from himself and onto someone else, instead. “Each of you knows the name and genius of him who stands first in the heart and confidence of American artists, the creator of your own parks and many other city parks. He it is who has been our best adviser and our constant mentor. In the highest sense, he is the planner of the Exposition — Frederick Law Olmsted.”

Burnham paused to let that sink in. Then he added: “An artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountainsides and ocean views. He should stand where I do tonight, not for the deeds of later years alone, but for what his brain has wrought and his pen has taught for half a century.” A collective roar went up among those assembled.

Burnham’s tribute provides a sense of Olmsted’s stature and importance. But, effusive as it is, it fails to do him full justice. His life and career were just too sprawling and spectacular. Ask people today about Olmsted, and they’re likely to come back with a few stray details — best case. But his achievements are immense. Olmsted may well be the most important American historical figure that the average person knows least about.

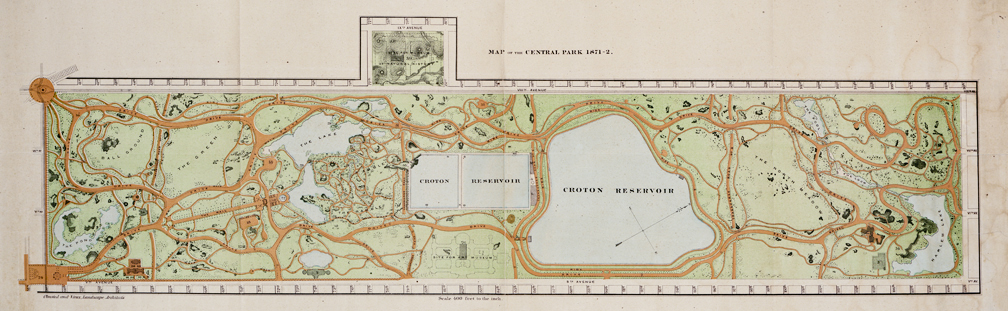

He is best remembered as the pioneer of landscape architecture in the United States. He created a number of classic green spaces, often in collaboration with his sometime partner, Calvert Vaux. Olmsted’s 1858 debut, Central Park, was a masterpiece, a rigid rectangle of land transformed into an urban oasis. His next effort, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, was another jewel.

With his landscape creations, Olmsted demonstrated a talent for wildly innovative designs that made use of a city’s best natural features. In Chicago, for instance, he noted that Lake Michigan provided a dramatic backdrop. For the 1893 World Columbian Exposition there, he drew the lake directly into the fairgrounds, dredging a series of canals, Venice-style. In Montreal, his scheme called for exposing crags of rock and planting tree species associated with high altitudes, thereby giving a modest hill the appearance of an imposing alpine peak. Thus was born the city’s majestic Mount Royal Park.

Often, Olmsted perceived that a city possessed a variety of landscapes suitable for parks. Why settle on a single tract? The insight spurred Olmsted and Vaux to invent the park system, a concept they debuted in 1868 with a set of three parks for Buffalo, New York. To insure that people could travel from one park to another, cloistered in greenspace all the way, their plan called for broad, tree-lined avenues. They even coined a term for these: “parkway.” (The term remains in use today, though it’s much abused, applied even to concrete medians planted with a few scraggly saplings.)

The park system proved a versatile concept, and Olmsted was prolific. He designed systems for the cities of Rochester, Milwaukee, and Louisville. He ringed Boston with a series of greenspaces — satisfyingly varied in terrain and design — that would come to be known as the Emerald Necklace.

But Olmsted wasn’t content to merely be a park-maker. So many other types of landscapes called out for his talents and touch. He designed the grounds of a number of private estates for wealthy patrons. He designed the campus of Stanford, Mount Holyoke, and other colleges and universities. He also designed city neighborhoods, the U.S. Capitol grounds, the grounds of several mental institutions, and a pair of cemeteries. For his landscape architecture achievements alone, Olmsted would have earned a measure of lasting fame. At a time when open space is at a premium, he’s left us a legacy of green in city after city.

But Olmsted was also an environmentalist. He managed to roam most of the country (“I was born for a traveler,” he once said), and, along the way, he realized that some of the most striking natural landscapes were under siege. He played a crucial role in the early efforts to preserve Yosemite and Niagara Falls, for example. Over time, he began to bring environmental considerations to his park work, as well. He designed Boston’s Back Bay Fens not only as a park, but as America’s first effort at wetlands restoration.

Preserving wild places is different from crafting urban spaces, and it’s a vital Olmsted role that is often overlooked. He needs to be given his due as a pioneering environmentalist.

[add more here about Yosemite and Olmsted's ideas for national parks]

But Olmsted was also a sailor and a scientific farmer, and a late bloomer nonpareil. During the Civil War, he helped manage the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a precursor to the Red Cross that managed hospitals and hospital ships. He also took a fascinating detour, moving out to California and managing a legendary but ill-starred gold-mining enterprise.

He was no dilettante, though. He simply did a lot of different things and did them well. It was the nineteenth century, and a younger nation was in the grip of a frontier mindset. All things seemed possible to many Americans. People didn’t have to carve out narrow areas of specialization. It was an ideal time for someone of Olmsted’s gifts. Seeking varied experience was his essence, as surely as Mark Twain’s essence was to turn a phrase.

At the same time, there’s a common theme that runs through many of Olmsted’s diverse endeavors. First, last, always, he was a reformer. No disrespect to Americans who came of age in the 1940s, often called the “Greatest Generation,” but Olmsted’s cohort (those who came of age in the 1840s) was pretty great in its own right. It was an especially socially conscious period in the country’s history, and it produced people who fought for the rights of the physically disabled and the mentally ill and — in the North — for the freedom of slaves.

Olmsted was very much a part of his generation. He didn’t become a scientific farmer merely as a way to make a living. He did so because, at a time when America was a predominantly agricultural nation, the vocation represented a chance to benefit society by demonstrating the latest cutting-edge practices. He became a maker of parks because, at a time when cities were becoming overcrowded and often unhealthy, they were a way to provide recreation and relief to the masses.

When it comes to reform, Olmsted also made most notable contributions as a journalist. That’s what Burnham alluded to when he said “his pen has taught” in his tribute to Olmsted.

During the 1850s, Olmsted traveled throughout the American South as a reporter for a brand-new paper, the New York Daily Times. (The paper later dropped Daily from its name.) His mandate was to approach the region almost like a foreign correspondent. In the course of his travels, Olmsted interviewed both white plantation owners and black slaves and produced a series of extraordinary dispatches — balanced, penetrating, humane. As a consequence, he managed to lay bare the evils of slavery in a way that other more polemical works of the era often did not. For Northerners anxious to understand the South in the tense years before civil war broke out, Olmsted’s dispatches were one of the best windows.

See also “Spying on West Virginia” by Tony Horwitz,

about Olmsted’s travels in the South

When war finally erupted, Olmsted’s writings from the 1850s continued to furnish a vital perspective, this time to readers in Britain where the government was undecided about whether to side with the Union or Confederate states. In 1861, Olmsted’s The Cotton Kingdom, an updated compendium of his collected Southern writings, was published in England and helped sway public opinion toward the Union cause. It remains in print to this day. While in prison, Malcolm X read The Cotton Kingdom and later credited Olmsted with providing a startlingly unvarnished look at the institution of slavery. In an introduction to the 1953 edition, historian Arthur Schlesinger described this classic book as “the nearest thing posterity has to an exact transcription of a civilization which time has tinted with hues of romantic legend.”

Olmsted did eventually settle down to work exclusively as a landscape architect. Demand for his designs was such that he really didn’t have a choice. But when finally forced to pick a career, he brought the sum of all his wildly varied experiences that had come before. That’s why Olmsted’s work is so gorgeous, so inspired, so dazzlingly set apart. It draws on the numerous disciplines to which he’d been exposed. When Olmsted created the landscape for the Biltmore Estate near Asheville, North Carolina in the 1890s, for example, he looked to memories of his long-ago travels throughout the antebellum South. When he designed the grounds for the 1893 World’s Fair, he drew on his experiences in China as a sailor a half century earlier.

Biographies of Oldsted have tilted into hagiography, casting him as a kind of radiant figure—a deeply devoted husband and sweet, gentle father. Such portrayals conflate his pastoral park creations with his personal demeanor, which is a mistake. Yes, he created beauty, but he was capable of being a very hard man.

But reading letters in different archives and deciphering Olmsted’s distinctive handwriting provide a more accurate and human portrait of Olmsted. He was a great artist and a hard-driving reformer, to be sure. He also happened to have had a strained marriage and serious tension within his family. In many ways, the two things were related.

Olmsted had a big life, but also a difficult one. He faced more — much more — than his share of tragedy, even by nineteenth-century standards. He contended with the untimely deaths of children, close relations, and dear friends. He suffered various physical ailments, such as the ravages of a near-fatal carriage accident. And he endured assorted forms of psychological torment: insomnia, anxiety, hysterical blindness, and depression. “When Olmsted is blue, the logic of his despondency is crushing and terrible,” a friend once said. Olmsted spent his final days in a psychiatric hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts; in a great irony, it was one which he had designed the grounds for.

He accomplished more than most people could in three lifetimes. As a park designer, environmentalist, and abolitionist, Olmsted helped shape modern America. He designed more than thirty major city parks and such planned communities as Riverside, Illinois and Druid Hills in Atlanta. His work on campuses included Amherst and American University in Washington, D.C, and assorted places such as the grounds of Moraine Farm in Beverly, Massachusetts.

He died in 1903, uncertain whether his creations would survive into the future. His proposition — maintain valuable center-city land as green space — was tenuous and vulnerable to the developers of housing tracts and racetracks and shopping districts. But Olmsted’s worst fears haven’t been realized. Instead, his creations have become centerpieces, points of pride for scores of communities across the country. Far from receding, Olmsted’s influence has only increased in the century since his death, growing and spreading like the Ramble in Central Park, his beloved wild garden.

Olmsted Brothers turned out to be a smashing success, far beyond anything he could reasonably have expected. Just as Olmsted was the foremost landscape architect of the nineteenth century, the firm run by his sons John and Rick became the preeminent practice for a new age. Much of its business involved circling back around to Olmsted’s original creations to do maintenance or to add modern touches, such as swimming pools. Olmsted Brothers did such work on their father’s parks in Chicago, Louisville, and Rochester, as well as Mountain View Cemetery. In 1908, the firm revised a plan for Bryn Mawr College that Olmsted had done some work on in the spring of 1895 — one of his very last projects.

Over time, Olmsted Brothers also built up an impressive list of original works such as Memorial Park in Maplewood, New Jersey, the grounds of the University of Idaho, and the Seattle park system.

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. fulfilled his uneasy destiny and truly became “leader of the van.” He helped Harvard, his alma mater, set up the first university course in landscape architecture ever offered in America. Following in his father’s footsteps, he also became a pioneering environmentalist. When the bill to create the National Park Service was written in 1916, he contributed some of the key language and phrases. He helped establish national parks in the Everglades, the Great Smoky Mountains, and Acadia in Maine.

Rick also served alongside Daniel Burnham on the prestigious McMillan Commission, which reorganized various Washington, D.C., public spaces such as the Mall, the White House grounds, and the Jefferson Memorial into a more coherent scheme. This experience pushed him farther into urban planning than his father had ever ventured. He drew up plans for the future growth of cities such as Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Boulder, Colorado. He also designed Forest Hills Gardens, a lovely and verdant 147-acre community smack in the middle of New York City (the community is not to be confused with nearby Forest Hills). This is Olmsted junior’s masterpiece as surely as Central Park is his father’s. Robert A. M. Stern, dean of the Yale school of architecture, described Forest Hills Gardens as “one of the finest planned communities ever.”

Olmsted Brothers carried on — in one form or another — for many decades. Along the way, the firm employed such notables as Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. and Arthur Shurcliff, known, among other things, as the landscape architect of Colonial Williamsburg. Marion Olmsted, who never married and continued to live at Fairsted, was also involved in the family business. A talented photographer, she took pictures of sites and even did some drafting work.

The firm continued well beyond John’s death in 1920, one year before Mary’s death. It was still going strong when Marion died in 1948. It even outlasted Rick, who retired in 1949 and died in 1957.

After there were no brothers involved in the business, the name was changed to Olmsted Associates (never mind that no Olmsteds were involved, period). The name held considerable equity, enough to propel the firm to 1980 — when the offices moved from Brookline to Fremont, New Hampshire — enough even to carry it all the way to 2000. In the final year of the millennium, the business finally shut down. By then, the impact on the American landscape of Frederick Law Olmsted and his successors was — quite simply — indelible.

And then there are all the names and terms that have entered the language — Olmsted loved to come up with these. Drive down any divided road, even one of terribly modest and uninspired design, and chances are it will be called a “parkway,” a term coined by Olmsted and Vaux. Visit the wild section of a fair, filled with rides and carnival barkers, and chances are it will be called the “midway.” That’s a nod to the Midway Plaisance, a stretch of Olmsted and Vaux’s original 1871 Chicago parks plan that wound up housing the Ferris wheel and other attractions during the 1893 World’s Fair. Or you can visit Millbrae, California. In 1865, the Bank of California president Darius Mills rejected Olmsted’s design for his estate. But the name that Olmsted suggested stuck, and today Millbrae is a community of 20,000 people just south of San Francisco International Airport. And then there’s Fenway Park. The home of the Boston Red Sox takes its name from the nearby place that Olmsted called the Back Bay Fens.

Yes, Olmsted is still very much with us. You can read his work; let one of his choice phrases “fall trippingly from your tongue,” as he once put it. Better yet, you can visit one of his green spaces. These transcendent creations provide a window into his spirit as surely as "Starry Night" evokes van Gogh.

Perhaps you have a favorite Olmsted spot. I know I do. I walk down the steps of Central Park’s Bethesda Terrace, past the Angel of the Waters statue, and make my way to the edge of the Lake. Then I follow the shoreline to the Bow Bridge and walk across. I like to stand at the water’s edge, soaking up this peerless composition: Vaux’s beautiful bridge, both spanning the Lake and reflected in it, and Olmsted’s untamed Ramble all around.

But this is so far beyond a mere work of landscape architecture. Looking around, I’m always struck by the variety of people — every income group, every nationality, young and old, enjoying a dizzying variety of activities. Here it is, the twenty-first century, and one of Central Park’s original purposes remains very much intact. In the truest sense, this place belongs to everyone. I think Olmsted would be proud.