In 1865 the riverboat hit a snag in the Missouri River and sank on the way to goldfields in Montana. Its hull discovered in a Nebraska cornfield gave up over 200,000 artifacts.

It would be a risky trip for the two young mothers, each of them bringing along two young children. On a beautiful Spring morning, the first of April, 1865, Caroline Millard and Mary Atchison boarded the steamboat Bertrand at the docks at Omaha, Nebraska. They planned to travel up the muddy, swirling Missouri River to the far end of civilization — the Montana Territory — to join their husbands who were partners in a banking operation in the rough gold mining town of Virginia City.

Caroline’s husband, Joseph Millard, had been one of the founders of Omaha and a partner in the Omaha National Bank, where he would later become President. Caroline was not happy that her husband had decided to open a gold exchange business in the frontier town. She was a genteel lady, involved in charity and social work, who distained the Montana frontier. Mary’s husband, John Atchison, was a notary and manager of the new Allen and Millard Bank in Virginia City. Mary traveled with their five-year-old son Charles and younger sister Emma, while Caroline Millard brought Willard aged four and Jessie two. It would be a difficult journey, but like many pioneer mothers they made sacrifices to keep families intact.

In the 1860s, a trip up the shallow, muddy Upper Missouri River was a risky proposition. Riverboats faced swift, changeable currents, sandbars, floating debris, high winds or tornadoes, and a scarcity of burnable fuel. Invisible snags, or trees stuck in the mud with sharp, broken-off limbs hidden below the surface of the water, could puncture a boat’s thin wooden hull and sink it in minutes. Steam boilers could explode or become clogged with river mud in their tubes, and paddlewheels break apart. And there were constant threats from Indian attacks on the crewmen sounding the water depth or searching for wood, or even on the boats themselves.

In the 1860s, a trip up the shallow, muddy Upper Missouri River was a risky proposition. Riverboats faced swift, changeable currents, sandbars, floating debris, high winds or tornadoes, and a scarcity of burnable fuel. Invisible snags, or trees stuck in the mud with sharp, broken-off limbs hidden below the surface of the water, could puncture a boat’s thin wooden hull and sink it in minutes. Steam boilers could explode or become clogged with river mud in their tubes, and paddlewheels break apart. And there were constant threats from Indian attacks on the crewmen sounding the water depth or searching for wood, or even on the boats themselves.

But good money could be made in the Montana Territory. In the early 1860s miners had discovered gold there and thousands of merchants, farmers, and others rushed to Alder Gulch and Virginia City, which became the territorial capital. As the Civil War neared an end, the Federal government moved military forces to the West to protect travelers from conflicts caused by transgressions on Indian land, building seven outposts on the Missouri River and other facilities.

This rapidly growing population required supplies, but farming and ranching were in their infancy in much of the Rocky Mountain area and could not meet demand. When bitterly cold weather closed the Missouri River in the winter, mining camps ran short of food, notably bacon, vegetables, coffee, sugar, and especially flour. During the particularly bad winter of 1864-1865, several wagon trains from Salt Lake City broke down, their oxen died, and precious supplies were lost. Flour was in short supply in Virginia City and its price shot up to $150 for a 100-pound sack. When rumors circulated that people were hoarding flour, the "Flour Riot" broke out. A group of vigilantes searched every business and house, confiscated 125 sacks of flour, and stored it in Leviathan Hall for safekeeping.

Merchants and riverboat companies back east saw opportunities for huge profit in trading with frontier outposts. At the time, about three-fifths of Montana's groceries, supplies, and equipment came up the Missouri on steamboats. In turn, gold came back down river and riverboats literally became treasure ships. In 1865 the St. Johns carried $200,000 in gold dust and 200 bales of furs and robes downriver from Fort Benton, and the Yellowstone carried $250,000 in gold dust as well as 3,000 buffalo robes. The next year, six boats from Fort Benton transported over $1 million in gold.

Caroline and Mary may have been comforted when they boarded the Bertrand and met her skipper, Horace “Lightning” Bixby, one of the most experienced captains on the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. When Samuel Clemons, who of course later took the name of Mark Twain, travelled down the Mississippi in 1857 with the intention of going to the Amazon to find his fortune in the cocoa trade, he was so impressed by Bixby, the captain of the riverboat he was travelling on, that Twain paid $500 to join him to as a cub pilot. The young man studied for eighteen months with Bixby.

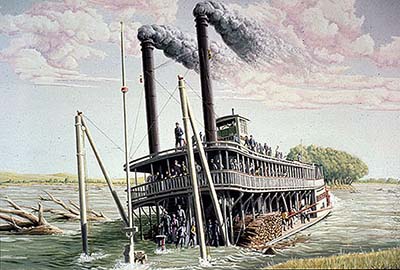

The Bertrand was, in many ways a typical steamboat modified to navigate the shallow reaches of the upper Missouri. Between 1831 and 1860, steamboat design changed dramatically to accommodate the needs of different river systems. By the mid-I860s, this evolution gave rise to fast, shallow draft “mountain boats” with a nearly flat bottom and extra width in proportion to its length. They extended commercial navigation farther and farther up the Missouri River.

The Bertand’s hull had been built in the summer of 1864 in Wheeling, West Virginia, an important boat-building center strategically located on the Ohio River near abundant supplies of white oak, a hard, flexible, and water-resistant wood. Bertrand was then rowed to Pittsburgh where master carpenter Peter Dunlevy built her cabins and superstructure. River pilots respected Dunlevy for building fast and light boats. They said that all you had to do to launch a Dunlevy boat was to pour a keg of beer over the bow and it would float on the foam. The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer reported that the Bertrand was "a nice trim little steamer, and it sits upon the water like a duck."

Even on a well-built boat, the first of April was early in the season to brave the cold, muddy water of the Missouri River, swollen by spring runoff. But time was not to be wasted. Transportation companies took great risks with their boats, cargoes, and passengers. Captains pushed high-pressure engines and boilers to their limits. The first boats to reach Montana would reap enormous profits for their owners and the merchants whose goods they carried to the winter-starved mining camps. Prices in Virginia City had rocketed so high that a single melon could sell for a dollar and fifty cents. Wheat sold for five to eight dollars a bushel, barley and oats twelve to fifteen cents per pound. One newspaper observed that, “If the farmers can't make their 'piles' at these prices – in gold, remember – they had better sell out to somebody that can."

The Bertrand pushed off at daylight and by 3:00 had reached twenty-five miles north of Omaha. “It was a beautiful afternoon, and we were sailing along in hopes of a quick passage,” recalled Caroline’s father, Willard Barrows, who was traveling with the family. “Most of the passengers at the time were lounging on their berths, or sitting about the boat, reading and conversing.”

But when the steamboat hit a snag on the port side, “our peaceful little home was changed into a fright, confusion, and almost despair,” recalled Barrows, “our plans for the future were all changed, and each was eager to save himself from the muddy waters of the Missouri. The chairs, tables and other furniture were thrown to one side; glass ware, crockery, skylight windows, and glass doors of the cabin were broken and creaking, the laboring vessel was parting and straining her timbers in rolling over. The screams of the women and cries of the children for a time passed description.”

Captain Bixby ran the boat toward the riverbank but it took on water and the “pretty little Bertrand” sank in five minutes in ten feet of water. While “no goods stored on the boiler deck or in the ladies’ cabin were wet, except as rolled off when the boat careened,” recalled Barrows, “the freight on the main deck, and in the hold of the vessel, about two hundred tons, mostly groceries, was nearly a total loss.”

Quick work by the crew swung a gangplank over to the shore, and passengers were able to walk to safety. A runner was sent to the nearest town, De Soto, about four miles away and a few of the women and children were taken by wagon to shelter before nightfall. The Bertrand’s crew erected temporary shelters with carpet and furniture from the boat for other passengers forced to spend the night.

Insurance underwriters had a difficult time that season on the Upper Missouri. Of twenty boats that left St. Louis that year, only six made it to Fort Benton in Montana Territory. Salvagers worked feverishly to recover the Bertrand’s cargo, but when the Cora sank in shallower water a couple of miles away, they switched to its cargo. Shortly after, on May 29, 1865, the A.E. Stanard wrecked in the snag-infested water between Florence and De Soto, Nebraska, and sank in deep water in five minutes, taking with it a large cargo of mining equipment.

Willard Barrows, Caroline Millard and their family eventually returned to St. Louis and boarded another riverboat on May 2 to head upstream again. “We passed the wreck of the Bertrand this afternoon, May 14th, and also the wreck of the steamer Cora, snagged five days since, and a total loss,” Barrows later recalled.

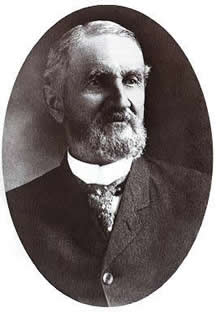

Eventually, they made it to Virginia City, but Mrs. Millard had no taste for the Montana frontier, and two weeks later she returned east. When it came to a choice between business and family, Joseph Millard decided the latter was more important. Allen and Millard sold the business in 1866 and Millard returned to Omaha with 100 pounds of gold in his wife’s clothing trunk. The following year, he would be one of the incorporators of the Omaha & Northwestern Railroad. He served as Mayor of Omaha in 1870-1871, a director of the Union Pacific Railroad, and later U.S. Senator from Nebraska.

Mary Atchison and her children joined John Atchison in Virginia City and remained in Montana. But most of their possessions never made it. When the Bertrand wreck was excavated, we found two boxes labelIed “TO J.S. ATCHISON, V. City,” and “TO ATCHISON, VIRINGIA CITY, MT.” Among the items were women’s shoes, children’s glove, picture frames, mirrors, a wicker sewing basket, a blue dressing gown, almonds, wall lamps, curtains, small lettered toy blocks, and a cast-metal toy horse cart.

Transition – Bertrand’s hull covered with mud. How the boat was discovered.

Text about excavation

What was surprising, interesting? Champagne from France, etc.

How did Switzer and his colleagues clean, preserve the materials?

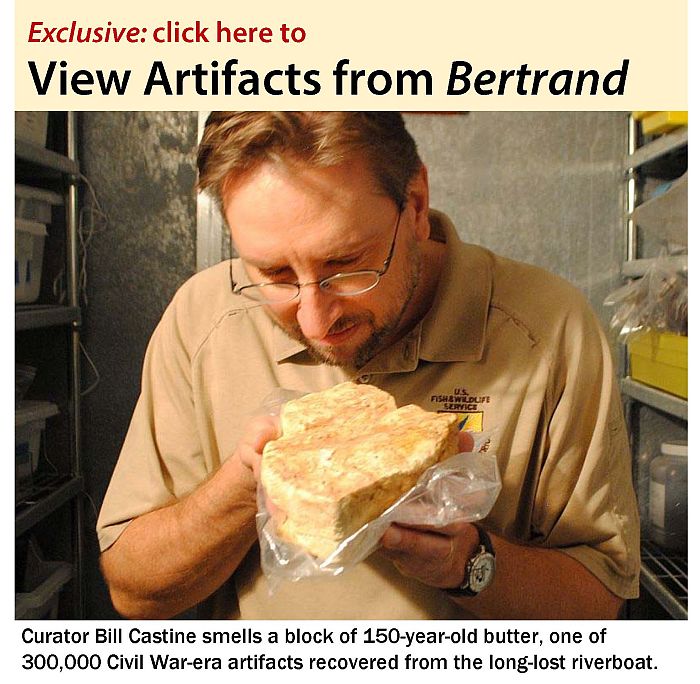

How were the fabrics and foodstuffs preserved? Clothing, butter???

Concluding paragraph about the importance of the collection, what we can learn.