Seventy-five years ago this June, the celebrated writer for The New Yorker was one of the first journalists to witness the carnage on Omaha Beach.

-

Spring 2019

Volume64Issue2

One of the hundreds of boats that the Allied air armada barreled past at 0700 on D-Day was LCIL-88, a Landing Craft, Infantry, Large, operated by the U.S. Coast Guard and carrying an elite band of demolitionists from the Sixth Amphibious Naval Beach Battalion. At that precise moment, LCIL-88 was hovering a mile or so off a beach that Allied planners had christened “Omaha.”

Bracing themselves against choppy seas, LCIL-88’s officers were standing on the bridge, peering through field glasses, trying to divine how the first wave of seaborne troops — infantrymen from the U.S. Army’s Blue and Gray Division, the 29th — was faring. From that distance it was tough to tell, but it didn’t look good. Huge plumes of smoke billowed from German artillery and 88’s, the deadly accurate antiaircraft and antitank guns. Every few seconds there was a concussive whoosh! as enemy gunners zeroed in on the boats in front of them. The splashes were getting closer and louder.

At exactly 0735 — 65 minutes after H-Hour — LCIL-88’s job was to clear a path for the next wave of invaders scheduled to hit the heart of Omaha. Its mission was to deposit the Navy demolition team, expert engineers who’d been trained to dismantle the insidious obstacles that German commander Erwin Rommel had planted to repel an attack. Allied planners called that section of the beach, apparently without irony, “Easy Red.”

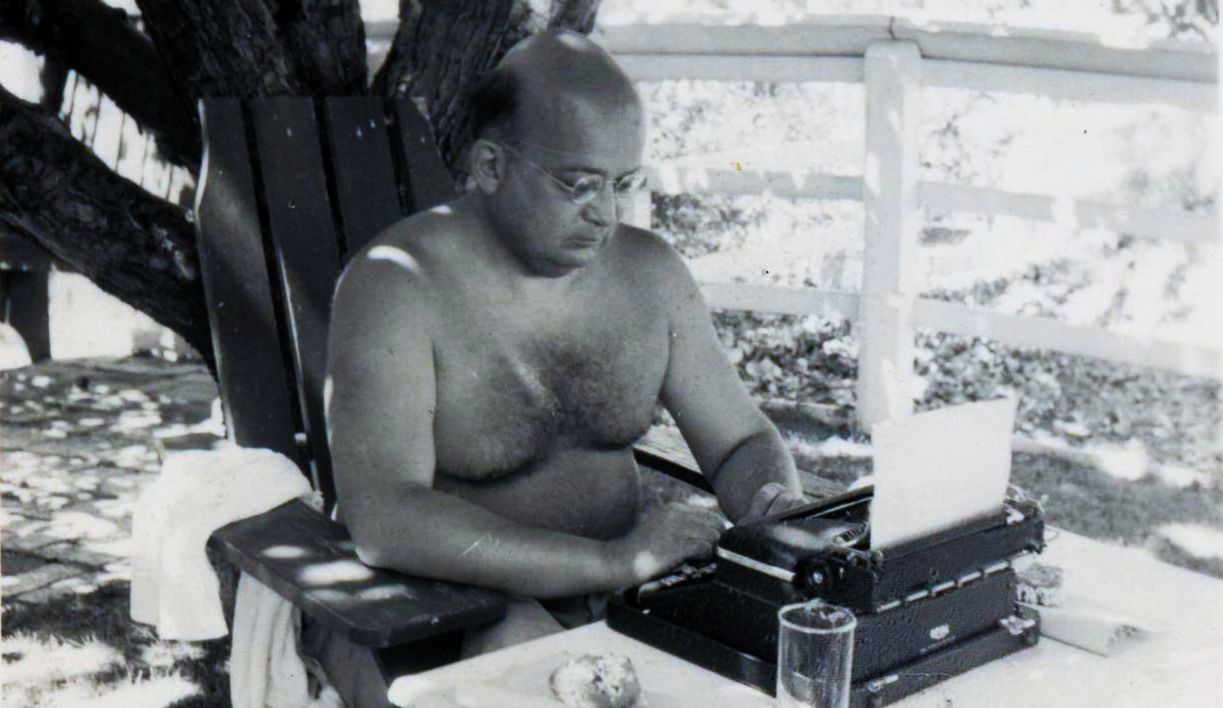

Perched next to the officers was a rotund 39-year-old writer with thick wire-rim glasses named Abbott Joseph Liebling. Liebling, scion of a wealthy New York family, owned a set of binoculars so powerful that he loaned them to the LCIL’s captain that morning.

The essayist was “A. J.” to readers of the New Yorker magazine but “Joe” to his friends - and in five days on board the LCIL, four of them spent docked at Weymouth, England, Liebling had made a lot of new friends. The Coast Guard and Navy men were tickled that an intellectual with an Ivy League pedigree could talk sports - especially prizefighting - with such relish. Liebling not only knew more about boxing than most cornermen, but loved to imitate his heroes, inducing howls as his chubby carcass pranced and jabbed, bobbed and weaved. He was also a dead-on mimic, the kind of guy who could eavesdrop on a snatch of conversation and instantly spoof both ends.

One of the crew members who got a kick out of Liebling was a chunky youngster from the District of Columbia. The other Coasties needled the D.C. kid about his habit of beginning every letter to a girl back home with: “Well, Hazel, here I am again.” The Coast Guardsman who served as the LCIL’s coxswain - the swabbie who lowered the ramp and plunged into the water to secure the anchor - had aspirations to be a journalist.

\Among the seamen in the Navy’s amphibious force (or as the Coasties kiddingly called it, the “ambiguous farce”) was a 22-year-old radioman from Kansas City, Kansas, named John Murphy. Young Jack was the kid brother of Associated Press columnist Hal Boyle’s sister-in-law. During the North African campaign earlier in the war, Boyle and Liebling had become jeep-mates and drinking buddies. Thanks to Jack and his cohorts, Normandy would soon reunite them.

Liebling was the least pretentious-looking correspondent in the ETO. Combat reporters weren’t necessarily matinee idols, but most tried to dress the part, sporting an aviator’s scarf or a tanker’s jacket or some other item that projected a martial image. Fashion affectation, though, was lost on Liebling, whose military-issue slacks fit so loosely they flapped in the breeze. Three decades later, fellow correspondent Don Whitehead remembered that Liebling “managed to look like a large, uncomfortable sack of potatoes.”

The potato-shaped boxing aficionado had begged the Army for an invasion assignment with foot soldiers. Liebling wanted to cold-cock Hitler’s Festung Europa with his First Division pals from Tunisia - and had a personal invitation from the First’s commanding general, Clarence Huebner, to hit the beachhead at Omaha. Many of the men in the “Big Red One,” as the First Division was known, were native New Yorkers, ethnic guys with “Toity-Toid Street” accents and attitudes to match - the streetwise cockiness that Liebling loved to celebrate in print.

After the Army press brass refused to honor Huebner’s proffer, Liebling accused them of perpetrating reverse snobbery. Nobody wanted to hand a plum invasion spot to some fat egghead from a snooty rag, he crabbed. But Liebling was lucky: two old friends, John Mason Brown, a once and future Broadway critic; and Barry Bingham, a prewar reporter with the Louisville Courier-Journal, were handling the Navy’s invasion-day press relations. Lieutenants Brown and Bingham arranged a berth for Liebling on LCIL-88, one of the first large landing crafts scheduled to hit Omaha.

When Francophile Liebling, who was almost as enamored of northern France as he was of New York City, learned four days before the invasion that Normandy was the objective, he remembered feeling “as if, on the eve of an expedition to free the North from a Confederate army of occupation, I had been told that we would land on the southern shore of Long Island and drive inland toward Belmont Park.”

Liebling had no idea until he arrived at Weymouth that the boat was skippered by an acquaintance. Before the war, Coast Guard captain Henry Kilburn “Bunny” Rigg had won prizes in yacht racing, and years later would be declared to be on “the all-star list of ocean racers” by Sports Illustrated. Occasionally, Rigg would write up his seafaring adventures for none other than the New Yorker. Liebling didn’t know Rigg well, but surely he viewed Bunny’s presence as a heartening omen.

Rigg’s gangplank greeting was so nonchalant it was “as if we were going for a cruise to Block Island,” Liebling wrote. But Rigg wasn’t leading a pleasure outing: the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had made it clear to journalists that once aboard a boat bound for the Channel, there was no getting off.

Liebling’s prewar critiques of New York’s dining scene had betrayed a weakness for the good life. He was both gourmet and gourmand: the thin gruel of service chow took some getting used to. On his first night on LCIL-88, before sitting down to a repast of frankfurters and beans, Liebling made mental notes as Rigg and the commanding officer of the beach battalion rolled out a remarkably detailed map of Omaha, buttressed by reconnaissance photographs of Easy Red that showed where the Germans had dug in pillboxes and artillery guns. Rigg pointed out a blockhouse on the bluff overlooking the beach, saying they could expect menacing fire from that area.

Eleven months earlier, the captain and his crew had weathered their share of action during the dicey landing at Licata in Sicily. Liebling was also comforted by the knowledge that the Coast Guard and Navy men had, together, been rehearsing their movements for weeks.

LCIL-88’s goal, Rigg said with a chuckle, was to give the Navy boys a “dry-ass landing.” Knowing that Liebling was worried about enemy guns as the craft maneuvered near the beach, the Navy commander, a Washington, D.C., attorney and Annapolis grad named Eugene Carusi, assured the writer that LCILs tended “to make a fairly small target bow on.” Carusi was Liebling’s kind of guy: he detested military chickenshit. His men loved him for it; they proudly called themselves “Carusi’s Thieves.”

Rigg knew that Carusi’s theory would be tested as, staring through Liebling’s binoculars at 0720, he sought the correct alleyway to Easy Red. If the team that stealthily surveyed Omaha’s attack routes before dawn had done its job, LCIL-88 would come across colored buoys to mark its path through the underwater mines, iron barriers, and concrete blocks. Not much went according to plan that morning at Omaha. But remarkably, the painted buoys were bobbing almost exactly where Rigg anticipated.

The Coast Guard captain turned to his staff and barked, “Mister Liebling will take his station on the upper deck during action.” It was Rigg’s felicitous way of telling his friend to stay the hell out of the way. Once topside, Joe watched Rigg send the craft surging toward the buoy-marked opening “like a halfback going into a hole in the line.” Rigg had spotted, dead ahead, two “spider” mines attached to a block of sunken concrete. He feathered LCIL-88 to ensure that it didn’t go anywhere near the tentacles sprouting out of the mines; the slightest brush would have been catastrophic.

D-Day’s beauty and pathos is distilled into what Liebling glimpsed that morning from his aerie on LCIL-88. After the boat sped back up, it soon encountered capsized vessels, a burning LCT (Landing Craft, Tank), and infantrymen floating in bloodied water, many with heads submerged. Other G.I.’s were struggling in water up to their necks. Fourteen years later Liebling was to write of the men in the water off Easy Red: “They seemed as permanently fixed in time and space as those Marines in the statue of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima.”

Tracer bullets, each with a descending arc, were zinging all around as Rigg swung LCIL-88 to the right. With machine gun bullets battering the boat, Liebling found himself shoulder-to-shoulder with a pharmacist’s mate. The two flattened their backs against the pilot house and sucked in their guts. Artillery explosions were ripping into the water; it felt like at any second the boat would founder. Noxious smoke was everywhere; the noise was deafening.

Moments later Liebling felt the craft run aground. He craned his neck toward the bow and saw that the landing ramp was somehow, miraculously, already down; his pal, the coxswain, clad only in bathing trunks and a helmet, had leapt into the surf. In spite of the pandemonium, the Navy men were rushing forward, rifles and demolition equipment in hand.

Liebling could hear an officer, probably Carusi, chanting, “Move along now! Move along!,” as if, Liebling wrote, “he were unloading an excursion boat at Coney Island. But the men needed no urging; they were moving without a sign of flinching.” Much of the enemy firing, Liebling surmised, seemed to be coming from the blockhouse on the right that Rigg had singled out.

Something scratched at the back of Liebling’s neck. Fearing the worst, he grabbed at it, and discovered that the ship’s cargo rigging, knocked loose by machine gun fire, had fallen around his shoulders “like a character in an old slapstick movie about a spaghetti factory.”

As Liebling rid himself of the rope, he glanced toward the stern. There he took in “a tableau that was like a recruiting poster.” Three enlisted men, one of them a black wardroom steward, were manning a 20-millimeter rapid-firing gun. Fluttering behind them was a crisp American flag that Rigg had broken out for the occasion.

Amid the din, Liebling heard the welcome rattling of the stern anchor being dislodged. Seconds later the boat was rocked by a blast. It was, Liebling later learned, a 75-millimeter enemy artillery shell that tore through the bulkhead and smashed through the ramp winch, disabling it.

“Pharmacist’s mates, go forward! Somebody’s hurt!” an officer yelled. Liebling’s pilot house pal and another medic scurried below. A Coastie came running by and screeched in Liebling’s ear: “Two casualties in bow!” By now, they had swung clear of the beach and were chugging toward deeper water. Captain Rigg almost forgot about the spider mines as he yanked his craft away from danger; the LCIL limped toward a designated area in mid-Channel where a hospital ship awaited.

To Liebling, whose ears ached and head throbbed, it had seemed like an eternity. But LCIL-88 had been anchored off Easy Red for just four excruciating minutes.

At roughly 0750 on D-Day, as LCIL-88 chugged out of range of shore guns, Liebling went down to the well deck, hoping its injured seamen weren’t seriously hurt. He stumbled onto a grisly scene. Permeating everything was a “shooting-gallery” stench. Since enemy shells had ripped into cases of rations, much of the deck was covered with food debris.

The news wasn’t good. Bloody body parts were splattered all over; the coxswain, the aspiring journalist, never made it back onto the boat. Two Coasties were gravely wounded; one of them was the D.C. youngster, Hazel’s would-be boyfriend. The other injured man “lay on a stretcher on deck breathing hard through his mouth,” Liebling wrote. “His face looked like a dirty drum-head: his skin was white and drawn tight over his high cheekbones. He wasn’t making much noise.”

Fifteen miles off-shore they linked up with the Dorothea Dix, a transport that had been converted into a hospital ship. LCIL-88’s wounded men had to be lifted to the floating sickbay in wire baskets.

At one point, a “Coast Guardsman reached up for the bottom of one basket so that he could steady it on its way up,” Liebling wrote. “At least a quart of blood ran down on him, covering his tin hat [and] his upturned face . . . He stood motionless for an instant, as if he didn’t know what had happened, seeing the world through a film of red, because he wore eyeglasses and blood had covered the lenses.”

A decade after the war ended, Liebling admitted that the unnamed Coastie had, in fact, been Liebling. “It seemed more reserved at the time to do it this way,” he wrote. “A news story in which the writer said he was bathed in blood would have made me distrust it.”

LCIL-88 clung to the transport area on D-Day morning, expecting at any instant to be ordered back to Omaha. But when no instructions came, Rigg and Liebling concluded, correctly, that the boys on Easy Red and all the rest were having too tough a time.

That afternoon, Liebling spotted an undamaged can of roast beef lying on the deck. “I opened it, but I could only pick at the jellied juice, which reminded me too much of the blood I had seen that morning, and I threw the tin over the rail.”

By early evening, the situation on Omaha had become less toxic; LCIL-88 soon began ferrying infantrymen from bigger boats to landing craft positioned closer to shore. Rigg and his men performed similar duties on D-Day plus-one and plus-two.

On June 9th, Liebling cadged a ride with a rocket-firing speedboat, which in turn transferred him to a Higgins craft that, fittingly enough, maneuvered onto Easy Red.

When Liebling neared the top of the cliffs he spotted bilingual signs. Above crudely drawn skulls-and-crossbones they snarled, “Achtung Minen!” and “Attention aux Mines!” It amused Liebling that the Germans had been caught so flat-footed they hadn’t had time to remove their own placards warning of minefields.

Liebling had visited Normandy several times in his youth; he had always pictured the Channel a brilliant shade of blue. Now in his mind’s eye it would forever remain a dull and depressing gray. But "I have D-Day now for all of my life," he wrote to Joe Mitchell at the New Yorker. "No one can ever take [it] away from me, but nobody can give me another D-Day, either."

Four years earlier, Liebling had fled his precious Paris just before the Nazis goose stepped down the Champs Élysées. Liebling had long dreamed of a triumphant return. But now machine gun nests and pillboxes and Panzer tanks and half of Hitler’s Wehrmacht stood in his way.

The article was excerpted from Timothy M. Gay’s 2012 book Assignment to Hell (New American Library), which was nominated for a Pulitzer, a Bancroft, and an American Book Award.