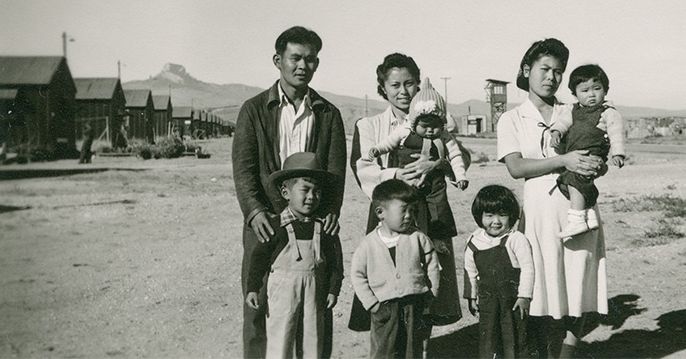

The thousands of Japanese-Americans interned in Wyoming during World War II maintained their dignity and community spirit.

-

October 2020

Volume65Issue6

Editor's Note: Tom Brokaw was the anchor and managing editor of NBC Nightly News for 22 years. Parts of the following essay appear as the foreword in a new book out this month, Setsuko's Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration, written by Shirley Ann Higuchi, chair of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. Her mother Setsuko was interned at the camp.

On the barren windswept corner of northwestern Wyoming there is a rocky outcropping called Heart Mountain, a bleak formation made up of limestone and ancient dolomite. It has little scenic or geologic appeal, but it is a sentinel for a profoundly shameful time in American history.

Heart Mountain overlooks the site of what can only be described as an American concentration camp. On the barren prairie leading up to it, the US government in 1942 hastily constructed a prison for Japanese Americans who were forcibly re-moved from their homes on the West Coast because they were thought to be potential agents for Tokyo’s warlords during World War II.

More than ten thousand American citizens of Japanese lineage arrived here in 1942 with only what they could fit on the train that transported them. Families of merchants, business owners, teachers, fishermen — the woof and warp of American life — were assigned living quarters in rudimentary barracks barely heated by smoky coal-burning stoves.

Each resident was given an army cot and two blankets. A hospital was established with outside medical personnel. One of the prisoners — euphemistically called “detainees” — had been a journalist, so he organized a weekly newspaper.

In a culture known for its enterprise, the Japanese prisoners on their own established schooling for the children and recreational opportunities. They organized schools, sports, Boy Scout troops, hobby clubs, and gardens. Reflecting its warped sense of values, the US government decided that draft-age young men should report for military duty.

When sixty-three resisters refused to serve until their constitutional rights had been restored, they were put on trial and sentenced to three years in prison. One young man jailed as a resister served his time and, when he was released, he joined the Army.

Who was the more authentic American? His jailers or this Nisei volunteer?

But in these deplorable conditions the Nisei maintained their dignity and their historic sense of family and community. They found entertaining ways to beat the draconian rules and manage the primitive conditions. When the war was over, they were released to go home, where many found their businesses taken over or so depleted it took years to restore their economic health. The US Navy seized the entire tuna fleet of an enterprising Long Beach fisherman, and he was never compensated.

Now, in a new century, the descendants of those confined to Heart Mountain have brought the story to contemporary Americans and the world by establishing a study center and restoring some of the old buildings.

Most important, they are determined that the stories, the legal and physical abuse suffered, the heritage of American citizens subjected to such an outrage, shall always be a part of our history, however painful the acknowledgment.

Since my first trip to Heart Mountain it has been deeply imbedded in my consciousness.