To this day nobody will take responsibility for the orphan dead of the 741st Tank Battalion.

-

May/June 1987

Volume38Issue4

This June 6 many ceremonies will mark the anniversary of the most massive amphibious invasion in history. One of them will be held at the U.S. military cemetery just east of Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, a small French village on the Normandy coast. At the cemetery are buried 9,386 American soldiers. But there are other GIs who died that day who do not rest at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. Assigned to lead the very first wave, the men who lost their lives in the forefront of the D-day invasion not only have been denied a decent burial but they have been denied their rightful place in history.

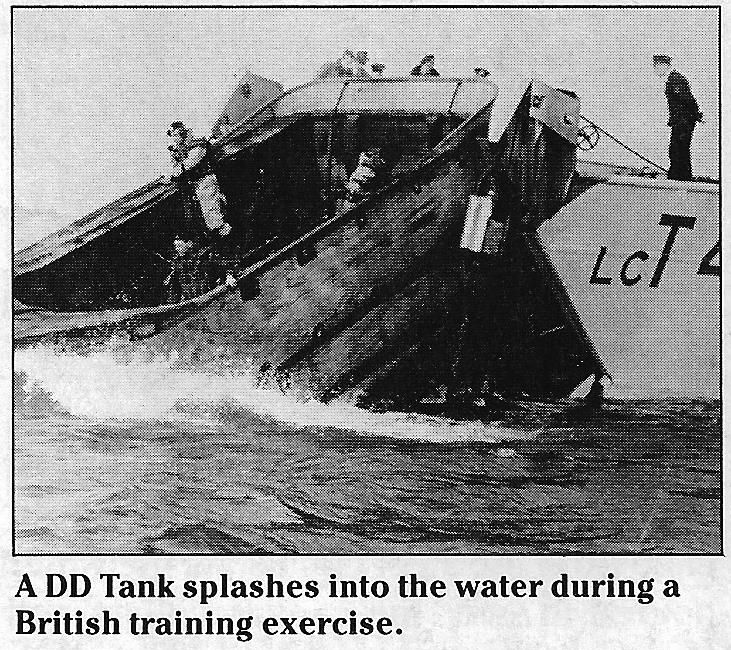

They were killed not by German gunfire but by their own weapon, an ultrasecret device that had been approved by the highest-ranking Allied generals. It was a weapon so exciting that the British general Frederick Morgan, who prepared the preliminary invasion plans, said, “At last was found that for which every army in the world had been searching for years....” Nicholas Straussler, a mechanical wizard from Hungary who had become a British citizen, had found a way to float the thirty-two-ton Sherman tank. A seven-foot-high “bloomer”—a canvas collar attached all around the sides of the tank—raised the turret above the waterline. The rest of the tank remained submerged; periscopes and tiller were added, and two propellers in the rear pushed it through the water. These twin screws also served as inspiration for the new miracle weapon’s name: Duplex Drive Tank, better known as the DD Tank. The name was meant to fool the Germans; no one was allowed to refer to it as a floating tank.

From shore the DD Tank looked like a small canvas boat and was unlikely to draw enemy fire. But once it hit the beach, it would lower its collar and burst out of the water already firing.

The supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, Gen. Dwight D. Elsenhower, was an old tank man himself, and his very first inspection trip after arriving in London was to see the new British device. Elsenhower, Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery, and the other admirals and generals assembled at a lake where the DD Tank was put into action. Eisenhower became so excited that he got on board one and steered it around the lake.

Gen. George C. Marshall had already approved the use of the DD Tank by the Americans, but because Eisenhower wanted to be sure this new weapon would be available in time, the day after the demonstration a special plane flew a British engineer with a complete set of blueprints to the United States. The tanks were manufactured in Ohio and shipped to England. This pleased Winston Churchill, who believed the floating tanks would be a vital part of the invasion and had pleaded for more of them. For the first time in history armor could precede infantry in an amphibious assault.

But not everyone liked the new weapon. The British Admiralty contended the DDs were unseaworthy. U.S. Maj. Gen. Charles (“Cowboy Pete”) Corlett, who had successfully commanded invasions in the Pacific, warned Eisenhower and the commander of the U.S. 1st Army, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, about the DDs’ instability. Corlett claimed he was “brushed off”; he “felt like an expert according to the Naval definition—a son-of-a-bitch from out of town.” Despite his experience, Corlett’s recommendations were ignored, nor was he given a D-day command. One of those who was, Gen. Joseph (“Lightning Joe”) Collins, had been assigned thirty-two of the swimming tanks, to be manned by the veteran 70th Tank Battalion. Collins, too, was concerned about the new wonder weapons. He was to lead the assault on Utah Beach, and when he saw the tanks launched from Navy landing craft during an exercise, he concluded there was “too small a margin for safety” in case of high seas. He asked that the DD Tanks be launched as close to shore as possible. The request was ignored.

Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow, an old friend of Eisenhower, was to command the forces invading Omaha Beach, the toughest section of the fortified coast. Gerow had little combat experience, and the sixty-four DD Tanks he had been allocated were to be manned by the untried 743d and 741st tank battalions. Unlike Collins, Gerow never protested the use of the new weapons, even though when he and the deputy chief of staff for plans, Col. Benjamin B. Talley, went to inspect them, the exercise was canceled with the explanation that even the moderate weather was too rough. Talley warned Gerow that such a fragile and sensitive weeapon would not be of much use in an invasion. But both Eisenhower and Bradley were enthusiasts as well as his superior officers; Gerow accepted the DD Tanks despite the most severe misgivings.

Two other officers raised serious doubts. Col. William Duncan, commandant of the DD Training School, and Lt. Dean Rockwell, the naval officer in charge of the DD Tank landing craft flotilla, issued official reports that the tanks could not withstand high seas and were very vulnerable to rough weather. Each member of the tank crew was issued a Mae West life vest, an air lung containing seven minutes of precious oxygen, a small rubber raft similar to those used by fliers, and a huge knife to cut through the seven-foot-high canvas collar. In theory, then, if a tank sank, the men inside had seven minutes to fight through the hundreds of pounds of pressure and out through the collapsed wet canvas into the freezing waters of the English Channel.

The GIs assigned to the project had little more than a month to be transformed into sailors, submariners, and navigators. D-day was scheduled for June 5,1944, but bad weather forced its postponement. Elsenhower felt he could not delay it again, and when the meteorologist predicted a short period of clearing, he decided to take the chance. The weather was still so poor that the Germans canceled their field exercises and a scheduled alert. The skies were clear enough for the planes to fly, but the seas had been whipped up into a frenzy by the previous day’s storm.

The GIs assigned to the project had little more than a month to be transformed into sailors, submariners, and navigators. D-day was scheduled for June 5,1944, but bad weather forced its postponement. Elsenhower felt he could not delay it again, and when the meteorologist predicted a short period of clearing, he decided to take the chance. The weather was still so poor that the Germans canceled their field exercises and a scheduled alert. The skies were clear enough for the planes to fly, but the seas had been whipped up into a frenzy by the previous day’s storm.

General Bradley was particularly worried about the DD Tanks assigned to Omaha Beach, but all he could do was hope that either the weather would improve or the commanders beneath him would manage to avoid a disaster. Both the Navy and his own staff had warned Bradley that the weather could doom the DD Tanks, but he failed to take action.

Bradley had insisted that the Army, rather than the Navy, decide when to launch the tanks from the landing craft. The fates of many men would be determined that day by very young Army captains. The commanding officers of the tank battalions had requested permission to accompany their men so they could make the crucial decision rather than leave it to junior, inexperienced men. The Navy turned them down.

Utah Beach was sheltered by the Cotentin Peninsula, and although the water was rough, it was not quite as bad as at Omaha Beach. The young lieutenant of B Company of the 70th Tank Battalion, Francis Songer, who had fought in Africa and Sicily, had so little faith in the DD Tanks that during training he ordered his men to reinforce all the seams in the tanks’ canvas collars with catgut and needles bought with his own money. On D-day the water was far rougher than any the men had encountered in training, and Songer’s battle experience made him wary of launching from so very far from shore. When the landing craft were still five thousand yards out, the Navy officer began to drop the ramp to start launching the DD Tanks. Songer protested that the water was too rough and they were still too far away. The Navy man screamed back that if they went any farther, they all would be blown up. Songer ordered him to keep moving. The closer in they came, the calmer the water, but the greater the danger of mines. One of the landing craft did hit a mine and sank, taking its four tanks to the bottom. But by this time they were just a mile offshore, and Songer gave the order to launch. All but one of the twenty-eight tanks was able to swim in.

The 743d Tank Battalion assigned to the western half of Omaha Beach was led by Capt. Ned Elder, an instructor at the DD Training School, who had never been in battle before. The Navy’s flotilla leader was Lieutenant Rockwell, who had issued the earlier report warning of possible hazards from the weather. The two saw the pounding seas were much rougher than the DD Tanks had been designed for. Despite all of the pressures, Elder and Rockwell decided not to launch—and thereby not only saved the lives of their own men but helped ensure that there would be tanks to fight on Omaha later that day. Ned Elder did not live long enough to appreciate fully the value of his decision; less than two weeks later he died in battle, leaving a new bride and a son he would never meet.

On the eastern half of Omaha Beach it was a very different story. The 741st Tank Battalion was led by a short, muscular Southerner, Capt. James Thornton, Jr., and a tall, aristocratic Yankee, Capt. Charles Young. As they approached Omaha, Thornton talked over the situation with the men on his landing craft. It was clear that the water was far rougher than anything they had previously encountered—the wind at the time was force three—but the men felt duty-bound to their mission. Thornton called Young on the radio, and the two men decided to go ahead and take the risk of launching. They did not consult the senior naval officer, whose landing craft had been separated from the others in the rough seas; he first learned of the decision when he saw Young’s landing craft suddenly drop anchor and start launching tanks while still almost six thousand yards from shore. The order was sent out to all the landing craft to launch, and despite its misgivings, the Navy went ahead. The senior naval officer launched the DD Tanks from his own craft, only to watch helplessly as, one after another, they sank almost instantaneously.

Twenty-nine tanks and about 145 men from the 741st Tank Battalion were thrown into the icy waters of the English Channel. Thanks to a fortunate accident, one landing craft was unable to launch its tanks and landed them safely onshore. But out of the twenty-nine tanks that were launched, just two were able to swim into the eastern sector of Omaha Beach.

Some of the tanks sank immediately, giving the men inside no chance to escape from the steel coffins. As the water poured in over the canvas collars and the seams burst, seconds made the difference. Those standing on the deck had to struggle with the seven-foot canvas wall that surrounded them in order to break loose. Even if a soldier did struggle free of the canvas, the thirty-two tons of sinking metal created a suction that could drag him to the bottom. One of the landing craft commanders added a personal postscript to his official report that read, “Needless to say, I am not proud of the fact nor will I ever cease regretting that I did not take the tanks all the way to the beach.”

The bombs of the Allied air attack had overshot Omaha, and the naval gunfire had undershot it. The German defenses were fully intact. With few tanks to support them, the troops were killed as they landed on the beach or were pinned down by gunfire. In some companies more than 80 percent of the soldiers on Omaha were never even able to fire their weapons. Col. George A. Taylor pushed his men forward that day with the words “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here!” For a while it was that close. Only the sacrifice of American lives pitted against German guns eventually overwhelmed the enemy. It was a costly victory.

In 1979 the mayor of Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer wrote a letter to inform the U.S. Army that some fishermen in his village had located sunken tanks off Omaha Beach. The mayor met with representatives of the Army and explained that he wanted “to return the remains of the soldier-heroes back to their families for final and decent burial.” A single Army diver with rented scuba tanks and no other equipment spent less than two days looking for the tanks. Because of the swift current and poor visibility, he did not find them. French fishermen assured the diver they had caught the tanks in their nets, and later French scuba divers actually saw them. But the chief mortuary officer for the Memorial Affairs Activity Program in Europe, John G. Rogers, called off the search. Later the program director in Washington told him not to make any further efforts because “disposition of remains funds are not available to finance the salvage of the tanks. The Army’s responsibility begins when the tanks are out of the water....” In true Catch-22 style, the Memorial Affairs Division’s position is that they will not initiate any further action to recover and bury the men of the 741st Tank Battalion until there is proof that there are bodies in the sunken tanks.

So the perhaps one dozen tanks and the men who went down with them remain where they sank, a few thousand yards from the U.S. military cemetery at Saint Laurent-sur-Mer. These were soldiers who had been asked to lead the first wave of the Allied landings on the European continent. They gave their lives attempting to reach the shores of France, but they seem destined to remain forever a few thousand yards away from their objective, their cemetery, and their countrymen.