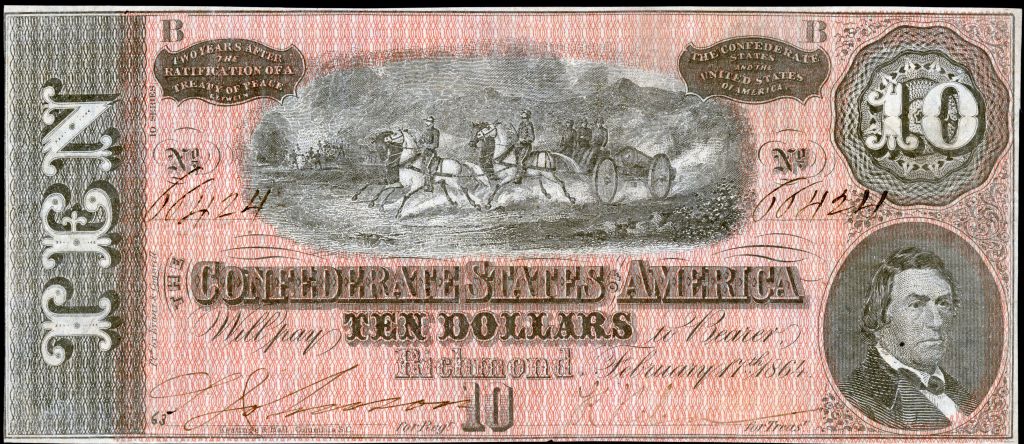

Our research reveals that 19 artworks in the U.S. Capitol honor men who were Confederate officers or officials. What many of them said, and did, is truly despicable.

-

June 2020

Volume65Issue3

The Civil War ended 165 years ago, but still casts a long shadow. In recent protests during which statues of Confederate heroes were torn down or defaced, many people have made it clear they will no longer tolerate public memorials to men who fought to keep Americans of African descent enslaved, and who caused the deaths some 365,000 members of the U.S. military. The Civil War caused pain beyond measure.

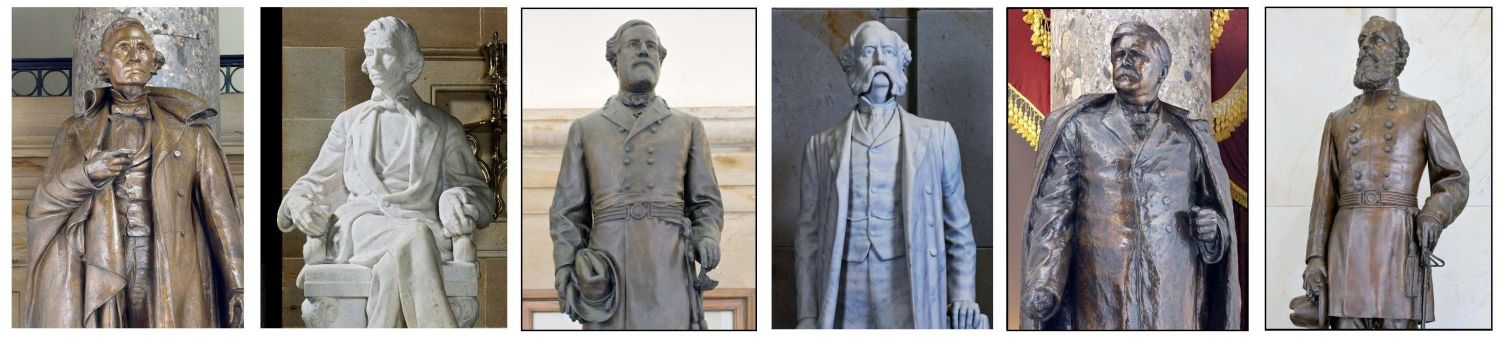

American Heritage has poured through lists of artworks in the U.S. Capitol and discovered that there are 19 statues, busts, and paintings of Confederates, not 11 as has frequently been mentioned. Below in this article is a list of these artworks and short bios of the men they depict.

“The halls of Congress are the very heart of our democracy,” Speaker Pelosi said in a letter requesting the removal of the statues. “The statues in the Capitol should embody our highest ideals as Americans, expressing who we are and who we aspire to be as a nation. Monuments to men who advocated cruelty and barbarism to achieve such a plainly racist end are a grotesque affront to these ideals. Their statues pay homage to hate, not heritage. They must be removed.”

Each state is allowed to be represented by two statues. At this point in our history, any state has many admirable figures to select from to represent them. Last year, for example, Arkansas voted to replace two figures from the Civil War with statues of music legend Johnny Cash and civil rights icon Daisy Lee Gatson Bates, although it hasn't happened yet.

Research into Confederate statues in the Capital can be a little difficult because for some reason they may not be included on the Architect of the Capitol's list of artworks representing their states (for example, Robert E. Lee is not on the list of artworks of people from Virginia, but he is on the AOC website, and Zebulon Vance is not on the North Carolina list.)

Democrats in the House have introduced a bill to remove the statues, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has insisted that a decision on statues in the Capitol should be left up to states.

"Every state is allowed two statues, they can trade them out at any time ... a number of states are trading them out now. But I think that's the appropriate way to deal with the statue issue. The states make that decision," McConnell told reporters.

It is good to remember that in the decades after the Civil War, men in Congress who only a few years before had fought desperately to kill each other, often in very brutal and personal ways, were able to work together to pass legislation that helped to build the great nation that emerged on the world stage in the 20th Century.

At least there is an important lesson in that history.

Here are short profiles of the Confederates honored in the Capitol.

| Alabama | |

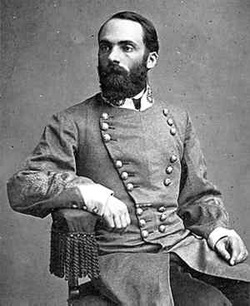

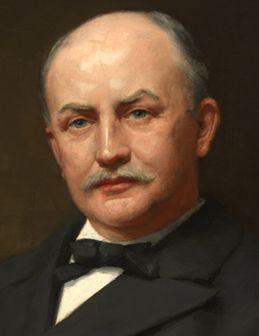

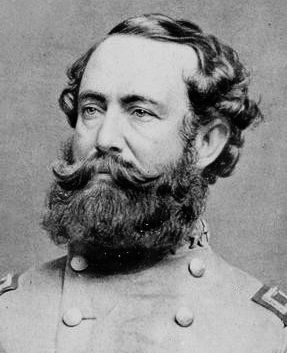

| 1. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, Statue, National Statuary Hall | |

"Fighting Joe" Wheeler was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy who joined the Confederate Army in 1861 as a cavalry officer. He rose to lieutenant general and fought in numerous battles including Shiloh, Corinth, Stones River, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Knoxville, Atlanta, and numerous other campaigns and engagements. After the war, he became a planter and lawyer, and served briefly in the House of Representatives, where he was said to have worked to heal the differences between Northern and Southern interests. Wheeler volunteered at the start of the Spanish-American War and was given command of a cavalry division that included Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders. He was senior officer present at the Battle of San Juan Hill. |

|

| Arkansas | |

| 2. Uriah Milton Rose, Marble Statue, Statuary Hall | |

One of the two statues representing Arkansas in the Statuary Hall is of Uriah Rose, a prominent judge and lawyer who helped formed the American Bar Association and served as its president. “Judge Rose was one of the great lawyers not only of Arkansas but of the United States,” wrote a fellow judge. Rose was initially opposed to secession because he felt the South couldn’t win a war against the North. But Rose actively backed the Confederacy throughout the War, serving as a state judge. When captured by Union forces, he refused to swear allegiance to the Federal government. After the War, Rose fought hard against the ratification of the Reconstruction Constitution. During the drafting of the state’s 1874 constitution ending Reconstruction, Rose stated that the document should “preserve ‘WHITE MAN’S government in a WHITE MAN’S COUNTRY’” |

|

| Florida | |

| 3. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, Statue, Capitol Visitor Center | |

Smith graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1845, and served in the Mexican War under General Zachary Taylor and General Winfield Scott. After the war he taught math at the Military Academy and fought in the cavalry on the frontier. Smith joined the Confederate forces and served as chief of staff to General Joseph E. Johnston at Harper's Ferry and helped organize the Army of the Shenandoah. While commanding a brigade in the army, he was severely wounded at Manassas. From 1863 until the end of the war Smith commanded the Trans-Mississippi department. He surrendered the last military force of the Confederacy and considered, but abandoned, a plan to settle in Mexico to form a slavery-based republic. Smith later served as president of the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company, chancellor of the University of Nashville from 1870 to 1875, and professor of mathematics at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. Smith died on March 28, 1893, at Sewanee, the last surviving full general of either army. |

|

| 4. Dr. Crawford W. Long, Statue, Crypt | |

Best known for discovering ether as an anesthetic, Crawford Long never fought in the Confederacy, but he did join a Confederate militia unit in Athens as a doctor. He was born in Georgia and attended the University of Georgia in Athens, where he was the roommate of future Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens. After obtaining his M.D. in Pennsylvania and studying in New York, Long returned to Georgia to practice medicine. In 1842, he used sulfuric ether as an anesthetic for the first time while surgically removing a tumor from a young boy. Long was a Whig, following family friend and statesman Henry Clay, and opposed Georgia’s secession from the Union. Still, after the state joined the Confederacy, Long accepted a post as physician to the University Campus Hospital in Athens, where he provided medical care to Confederate soldiers. Following the war, Long applied for and received a presidential pardon for his service on behalf of the Confederate government. He has since had many statues, museums, and hospitals named in his honor. |

|

| Georgia | |

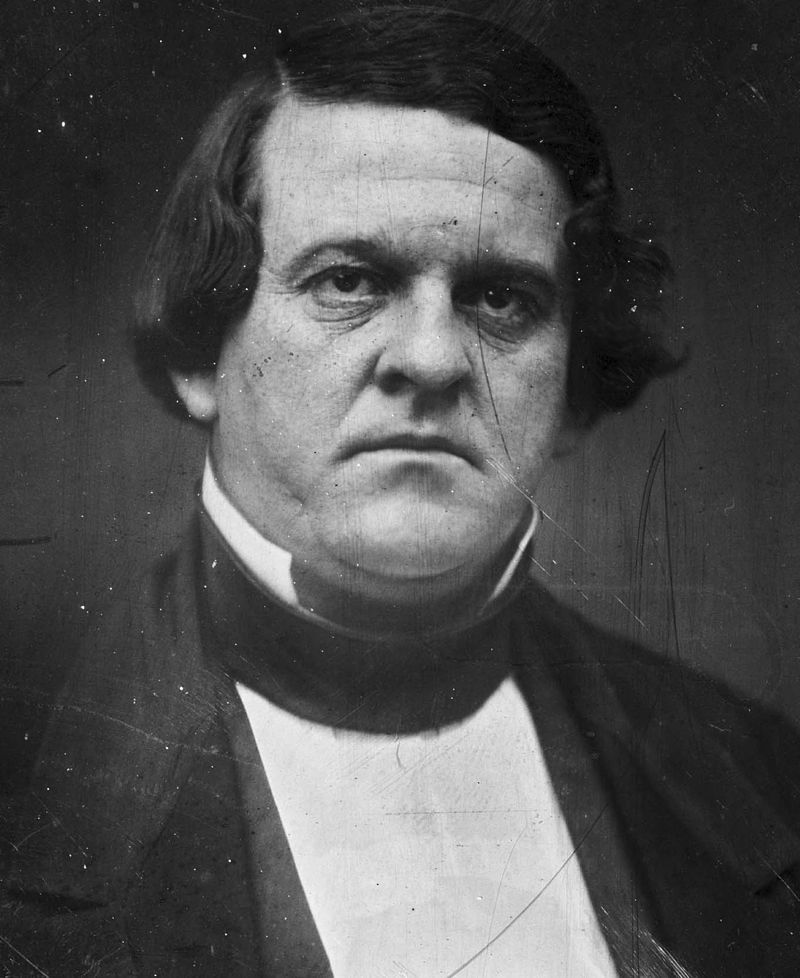

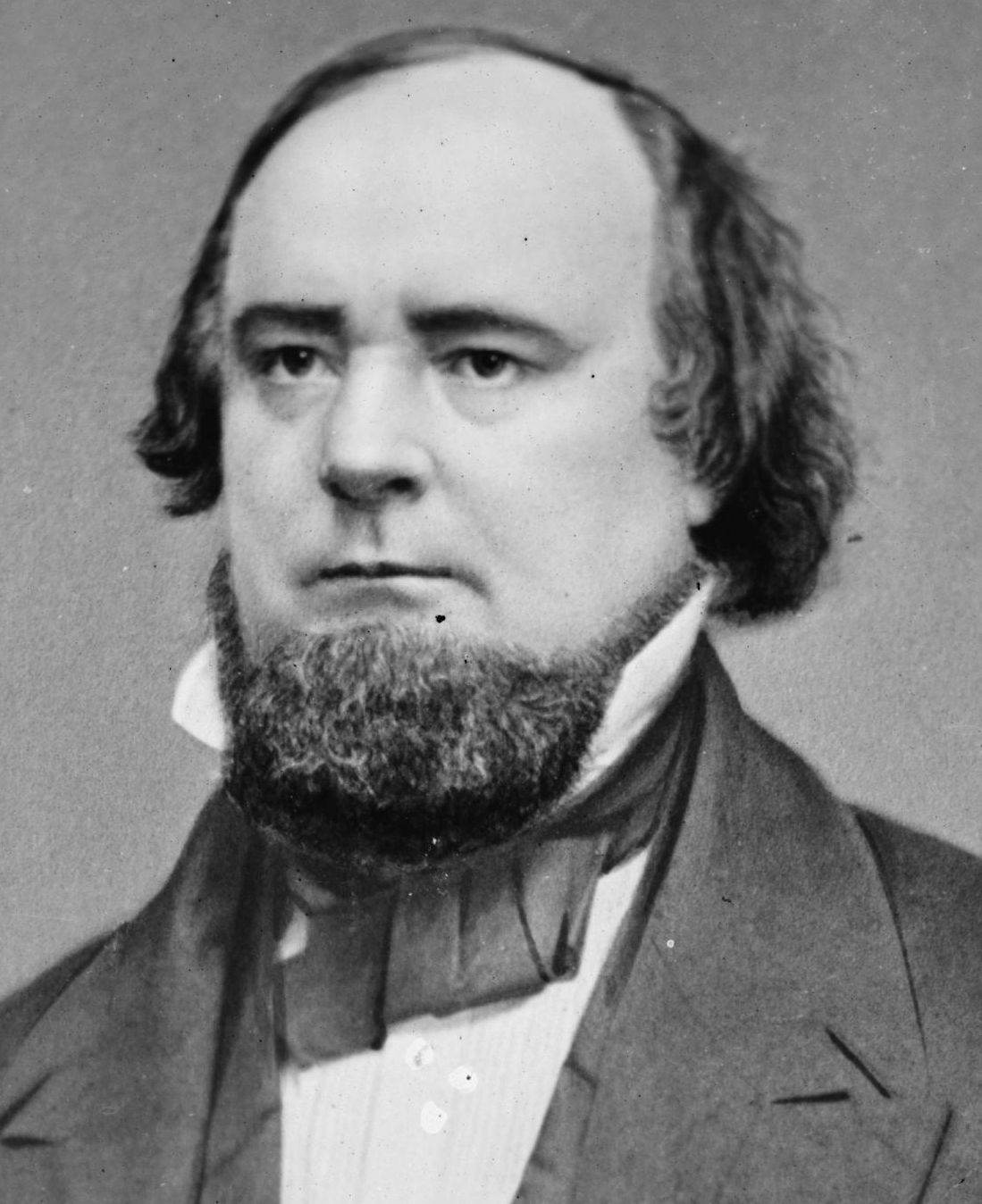

| 5. Howell Cobb, Painting, Speaker’s Lobby (Removed) | |

Cobb was a five-term member of the House of Representatives and elected Speaker in 1849 at the age of 34. After serving as Speaker for one term, he resigned to become governor of Georgia. He also served as Secretary of the Treasury in the Buchanan Cabinet. Cobb was one of the founders of the Confederacy. He served as the President of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, as the delegates of the Southern slave states voted to declare that they had seceded from the United States and created the Confederate States of America. “If slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

As an infantry general in the Confederate Army, Cobb served the entire war and fought in numerous campaigns. He suggested the creation of Andersonville Prison, where 13,000 Union POWs died. Cobb also argued against the idea of enlisting slaves into the army. “You cannot make soldiers of slaves, or slaves of soldiers,” said Cobb. “If slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” |

|

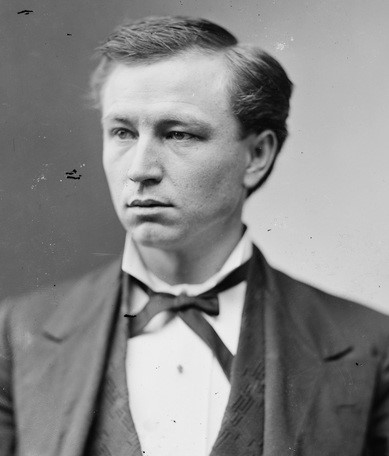

| 6. Charles Crisp, Painting, Speaker’s Lobby (Removed) | |

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Crisp enlisted in the 10th Virginia Infantry and was commissioned a lieutenant. He served with that regiment until May 12, 1864, when he was taken prisoner at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. After the war Crisp studied law and passed the bar. He was elected to Congress from Georgia in 1882, and served until his death in 1896. From 1890 until his death, he was leader of the Democratic Party in the House, as either the House Minority Leader or the Speaker of the House. |

|

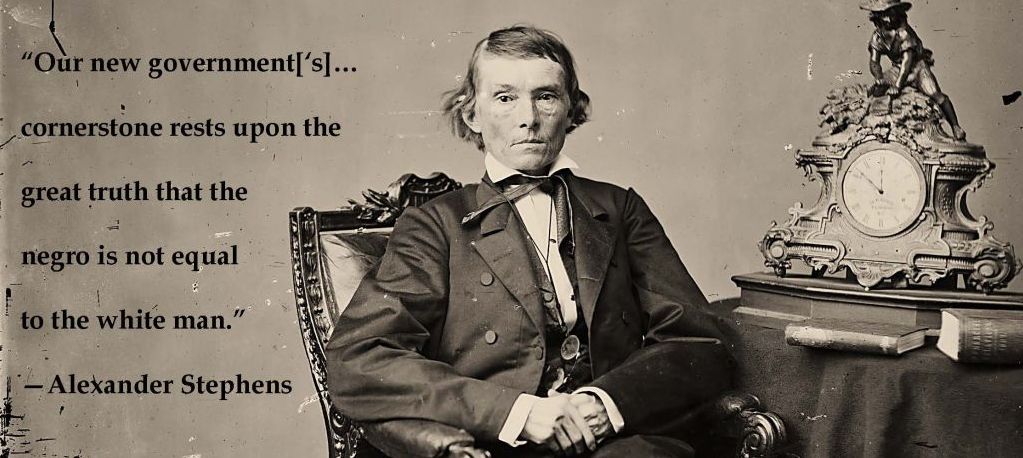

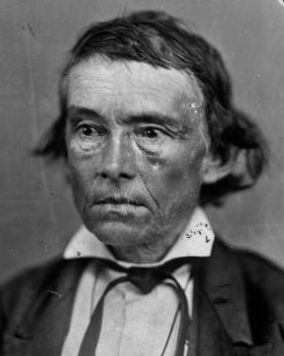

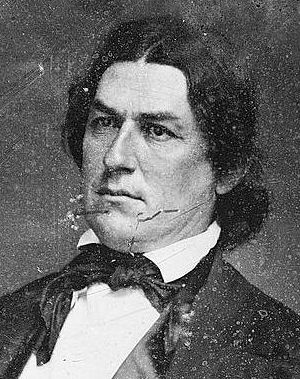

| 7. Alexander H. Stephens, Marble Statue, Statuary Hall | |

As a Congressman from Georgia from 1843 to 1859, Stephens actively participated in the most important slavery debates of the period including the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska and Fugitive Slave Acts. He was on the wrong side of history on all those important debates. Alexander Stephens is often considered one of the great villains in American history for his “Cornerstone Speech.”

Stephens is often cast as one of the great villains in American history. After leaving Congress in 1859, he delivered one of the most famous speeches in our nation’s history in March 1861 – an eloquent rallying cry calling for Southerners to secede. It's now known as the “Cornerstone Speech” because Stephens insisted that white supremacy and slavery were the “cornerstone” upon which secession was based. There were other reasons, too: states rights, tariffs, funding of public works, etc. But slavery was the foundation. Stephens' words helped to inflame the South and bring on the bombardment of Fort Sumter a few weeks later.

|

|

| Kentucky | |

| 8. John C. Breckinridge, Bust, Senate Chamber | |

Breckinridge served as Vice President of the United States from 1857 to 1861. Still in the U.S. Senate at the outbreak of the Civil War, he was expelled after joining the Confederate Army. Jefferson Davis made Breckinridge a major general and corps commander, and he fought in such important battles as Shiloh, Vicksburg, Murfreesboro, Stone's River, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, New Market, Cold Harbor, Monocacy, Winchester, and Bull's Gap. At the battle of Saltville, his troops massacred African-American troops although Breckinridge had not ordered the action. Breckinridge was widely respected by his fellow generals, although he often disagreed with this superior, Gen. Braxton Bragg. Breckinridge resigned from the CSA in 1865 and was appointed Secretary of War by President Davis on January 19, 1865. After the war, he fled to Canada until Pres. Andrew Johnson declared an amnesty on December 25, 1868. |

|

| Louisiana | |

| 9. Edward D. White, Statue, Capitol Visitor Center | |

A native of Louisiana, White left Georgetown University in 1861 to enlist in the Confederate Army. He served for most of the war. After the war, White practiced law in Louisiana and served in the state's Senate and Supreme Court. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1890 and served until 1894, when he was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Cleveland. White was named Chief Justice by President Taft in 1910 and served until his death in 1921. |

|

| Maryland | |

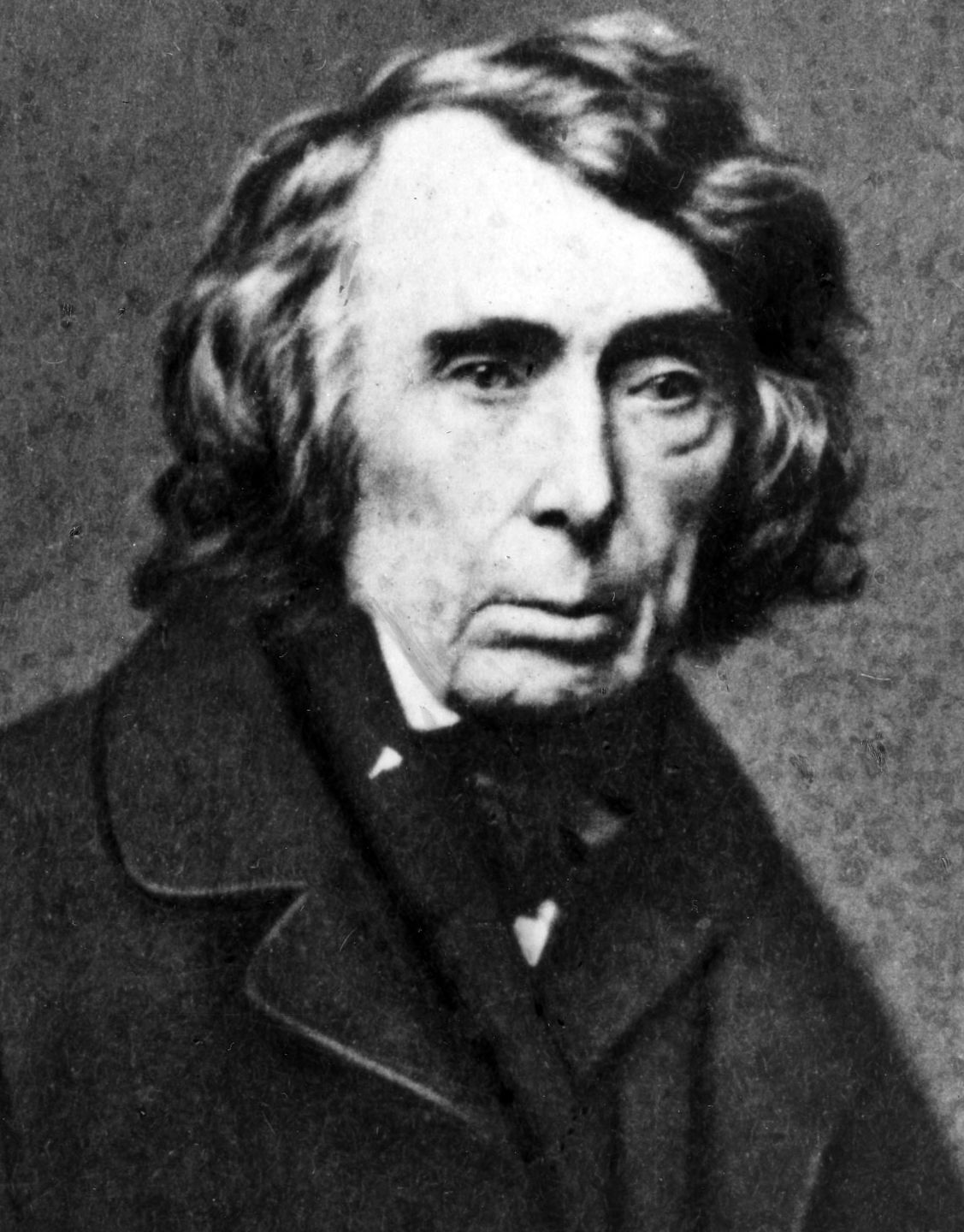

| Roger B. Taney, Bust, Old Supreme Court Chamber | |

Taney is not counted as one of the Confederates on this list, but is included because of the pivotal role he played before and during the Civil War as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court with unabashed pro-slavery leanings who opposed many of Lincoln's policies. Taney owned a large plantation in Maryland, a slave state until the end of the Civil War. Although he did free his slaves, Taney wrote in his opinion for the controversial 1857 Dred Scott case that black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.” Taney claimed that a “perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery.” As the Civil War unfolded, Taney sympathized with the seceding states, but he did not resign from the Supreme Court. He actively opposed many of Lincoln's actions. |

|

| Mississippi | |

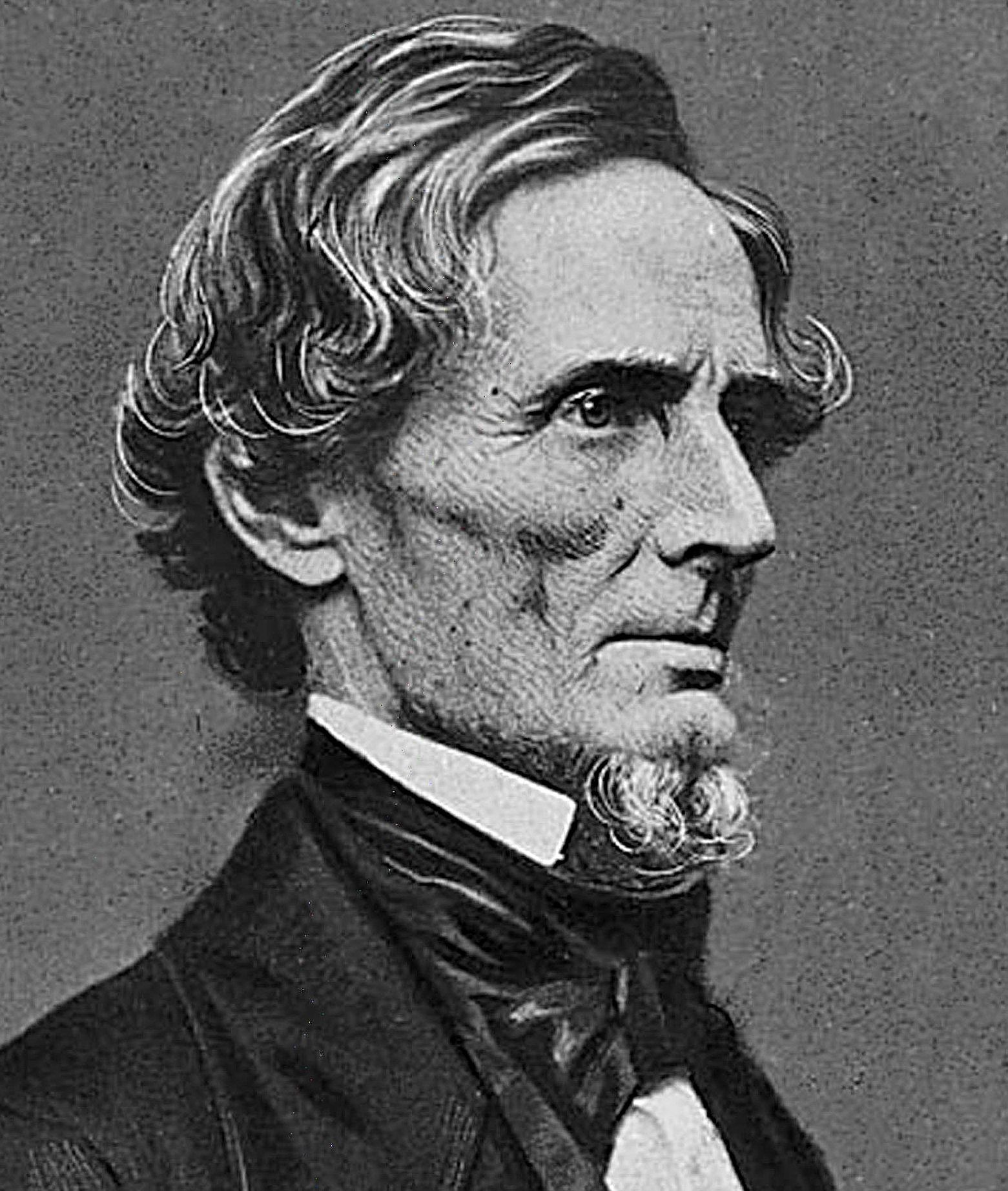

| 10. Jefferson Davis, Bronze statue, Statuary Hall | |

Jefferson Davis was the Confederacy's first and only president, serving from 1861 to 1865. Born in Kentucky but raised in Mississippi, he attended West Point and fought briefly in the Black Hawk War of 1832 before returning to Mississippi to run a cotton plantation. Davis was active in politics well before the Civil War. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1845, but resigned a year later to fight in the Mexican-American war. He entered the U.S. Senate the following year, and in 1853 was appointed U.S. Secretary of War by President Franklin Pierce, serving with distinction. Throughout, Davis was an ardent supporter of state’s rights and the institution of slavery, though he did caution against secession in the lead up to the war. In 1861, despite his own misgivings – he had wanted a military command – the Confederate Congress elected Davis president. As president, Davis presided over a number of significant battles and events. It was Davis who ordered the first attack on Fort Sumter, triggering all-out war with the North. He appointed Robert E. Lee to command the Army of Virginia in 1862, approving several offensives – many of them failed – throughout the conflict. At one point, he also appealed to Europe for assistance in the South’s effort. In 1865, Davis was captured by Union forces in Georgia and imprisoned in Virginia for two years. He was never tried for treason. See "Was Jefferson Davis Captured In A Dress?" |

|

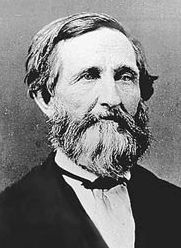

| 11. Col. James Zachariah George, Bronze Statue, Statuary Hall | |

As a member of the Mississippi Secession Convention, George signed the Ordinance of Secession. He joined the Confederate Army during the Civil War and served as a colonel. He was captured twice and spent two years in prison. After the war, he returned to the practice of law. George represented Mississippi in the Senate from 1881 until his death in 1897. He also served as a member of the Constitutional Convention of 1890 that created a new constitution to prevent the state's African-American citizens from voting, and successfully defended it before the Senate and Supreme Court. |

|

| North Carolina | |

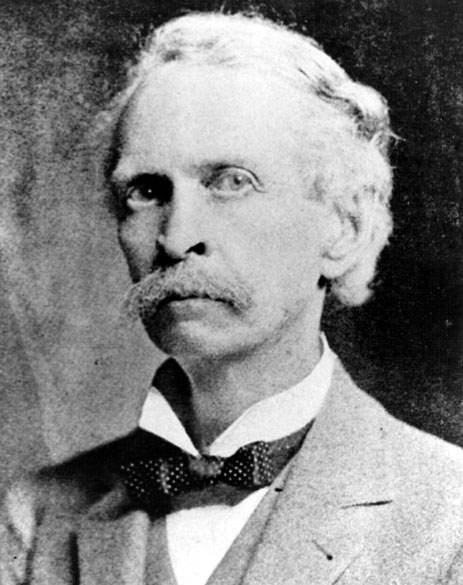

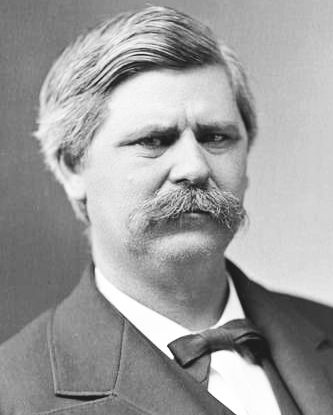

| 12. Zebulon Baird Vance, Bronze Statue, Statuary Hall | |

Zebulon Baird Vance was a lawyer who signed up in the Fourteenth North Carolina Regiment before the War even started and was promoted to colonel. He fought at a couple of engagements, but resigned after he was elected governor of North Carolina in September 1862. In 1879 he was elected to the U.S. Senate where he served until his death in 1894. A prolific writer, Vance became an influential leader in the postbellum era. As a leader of the “New South”, Vance favored the rapid modernization of the Southern economy, railroad expansion, school construction, and reconciliation with the North. |

|

| South Carolina | |

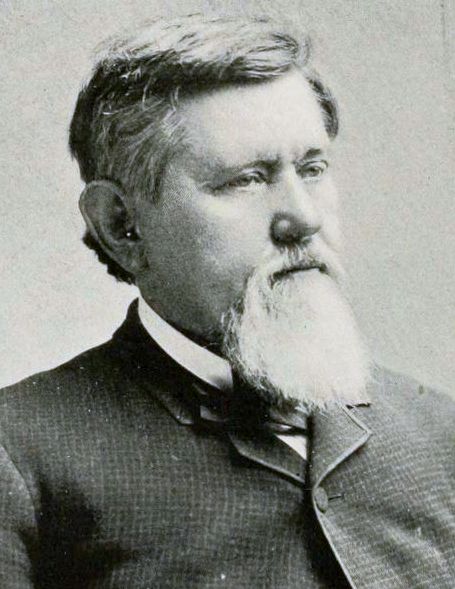

| 13. James Lawrence Orr, Painting, Speaker's Gallery (Removed) | |

James Orr served five terms in Congress, including one term as Speaker of the House. At the beginning of the Civil war, Orr organized and commanded Orr's Regiment of South Carolina Rifles. He resigned from the CSA in 1862 and entered the Confederate Senate, where he served as chairman of the influential Foreign Affairs and Rules committees. After the war, he served as governor of South Carolina. In 1872 President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him to be Minister to Russia in a gesture of post-Civil War reconciliation. |

|

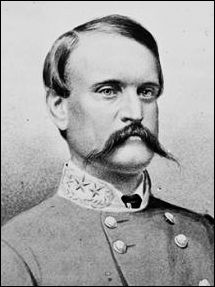

| 14. Gen. Wade Hampton, Marble Statue, Statuary Hall | |

Born in South Carolina, Wade Hampton III was descended from a long line of prominent Southern politicians and plantation owners. His family was one of the wealthiest in the Southeast, and also owned one of the largest populations of slaves. Hampton III was elected to the South Carolina General Assembly in 1852 and served as a state Senator from 1858 to 1861, at which point he resigned to join the Confederate Army. During the war, Hampton distinguished himself as a capable military leader. He led a force known as “Hampton’s Legion,” which he personally financed and raised using his cotton fortune, and was present at many major battles, including Gettysburg. Following the war, Hampton returned to South Carolina politics, becoming a leader of the “Lost Cause” movement as well as of the “Redeemers,” a political coalition formed to restore white rule following Reconstruction. The faction helped get him elected governor in 1876, a position he held until entering the U.S. Senate in 1879. |

|

| Tennessee | |

| 15. John Bell, Portrait, Speaker's Lobby | |

John Bell was one of the most prominent American politicians before the Civil War. He represented Tennessee in the House from 1827 to 1841, and was elected Speaker for the 23rd Congress. Bell served in the Senate from 1847 to 1859, and briefly as Secretary of War during the administration of William Henry Harrison (1841). Although a slaveholder, Bell opposed the expansion of slavery in the 1850s and campaigned vigorously against secession before the Civil War. In the race for President in 1860, often called “America's oddest election,” Bell played a critical role as the candidate for the Constitutional Union Party, a third party which took a neutral stance on slavery. The four major candidates split votes allowing Lincoln to win with only 39.8% of the votes cast. But after Fort Sumter in April 1861, Bell abandoned the Union cause, returned to Tennessee. and called for the state to join the Confederacy. The move angered many of Bell's former friends. Horace Greeley said that he had brought an “ignominious close” to his public career and the editor of the Louisville Journal wrote that the decision to support the Confederacy brought “unspeakable mortification, and disgust, and indignation” to Bell's former supporters. When the Union Army occupied Tennessee in 1862, Bell fled to Alabama, and later to Georgia. He died in 1869. |

|

| Virginia | |

| 16. Robert M.T. Hunter, Painting, Speaker's Gallery (Removed) | |

Robert M.T. Hunter was a Virginia lawyer and plantation owner who served eight years in the House of Representives including as Speaker (1839-41). He was also a U.S. Senator from 1847 to 1861. He owned an estimated 120 slaves on his plantation northeast of Richmond. Hunter was expelled from the U.S. Senate in 1861 and became Secretary of State of the Confederacy, and later a Confederate Senator (1862–1865). Like numerous other high-ranking Confederates, he was a frequent critic of President Jefferson Davis.

|

|

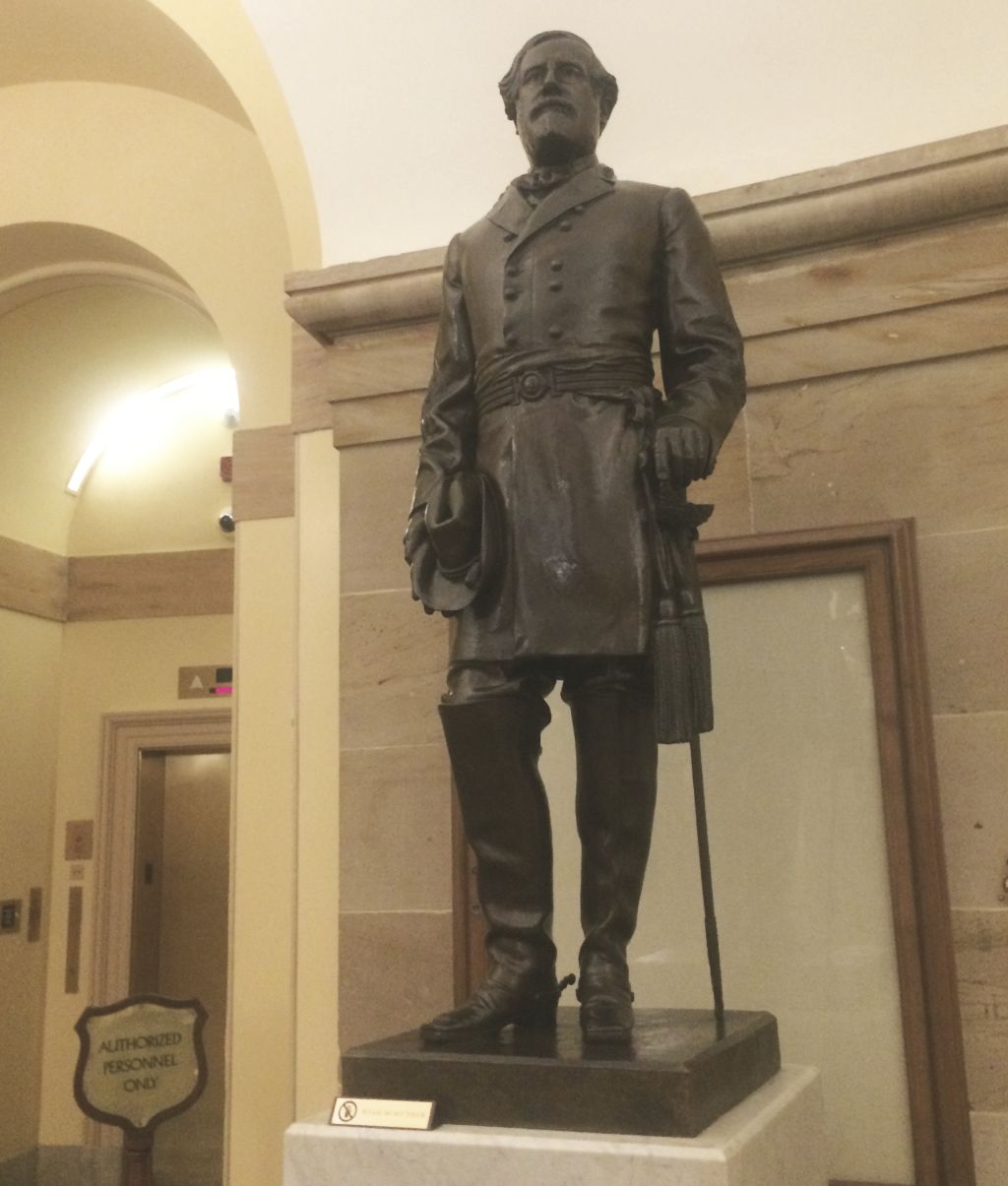

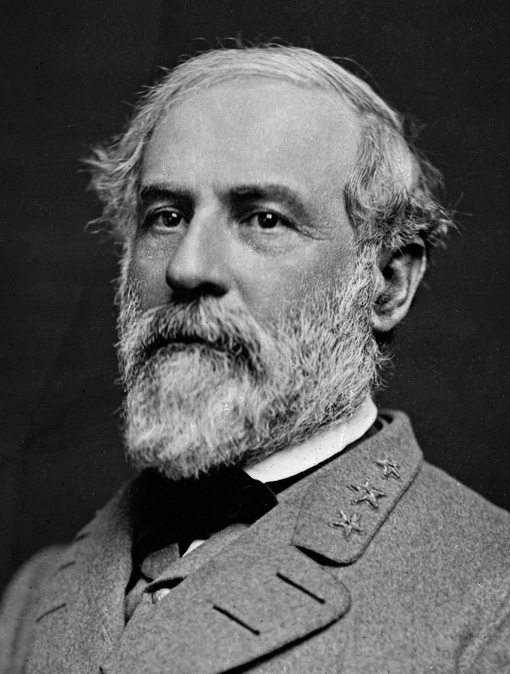

| 17. Gen. Robert E. Lee, Bronze Statue, Crypt (removed) | |

Although it is not listed on the Architect of the Capitol’s website, a statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee stands in the building’s crypt. It honors a man who led Confederate troops in 14 battles, causing an estimated 126,000 U.S. Army casualties. Lee’s role as Rebel Commander in the Civil War has made him one of the most–if not the most–divisive of Confederate figures. Born to Revolutionary War hero Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee in Virginia, Lee attended West Point before serving as an officer in the Corps of Engineers. He fought in the Mexican-American War in 1846, then served as superintendent of West Point, establishing himself as one of the highest-profile officers in the U.S. Army. His standing was such that Abraham Lincoln, upon the Civil War’s outbreak in 1861, offered him command of federal forces–an opportunity Lee turned down to join the Confederacy when his home state seceded that same year (Lee, whose positions on slavery have been hotly debated, argued that he could not fight against “his own people”). After serving as military adviser to President Jefferson Davis, Lee was tapped to relieve Joseph E. Johnston of his command of the Army of Virginia in 1862. His fighting force became one of the Confederacy’s most successful, leading bloody battles at places like Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. A victory in the latter battle convinced him to invade the North a second time, but he soon suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg. He was forced to surrender to the Union Army at Appomattox Court House in 1865, just two months after being named General-in-Chief of all Confederate forces. Following the war, Lee returned home to Virginia and took a position as president of Washington College. He died five years later. |

|

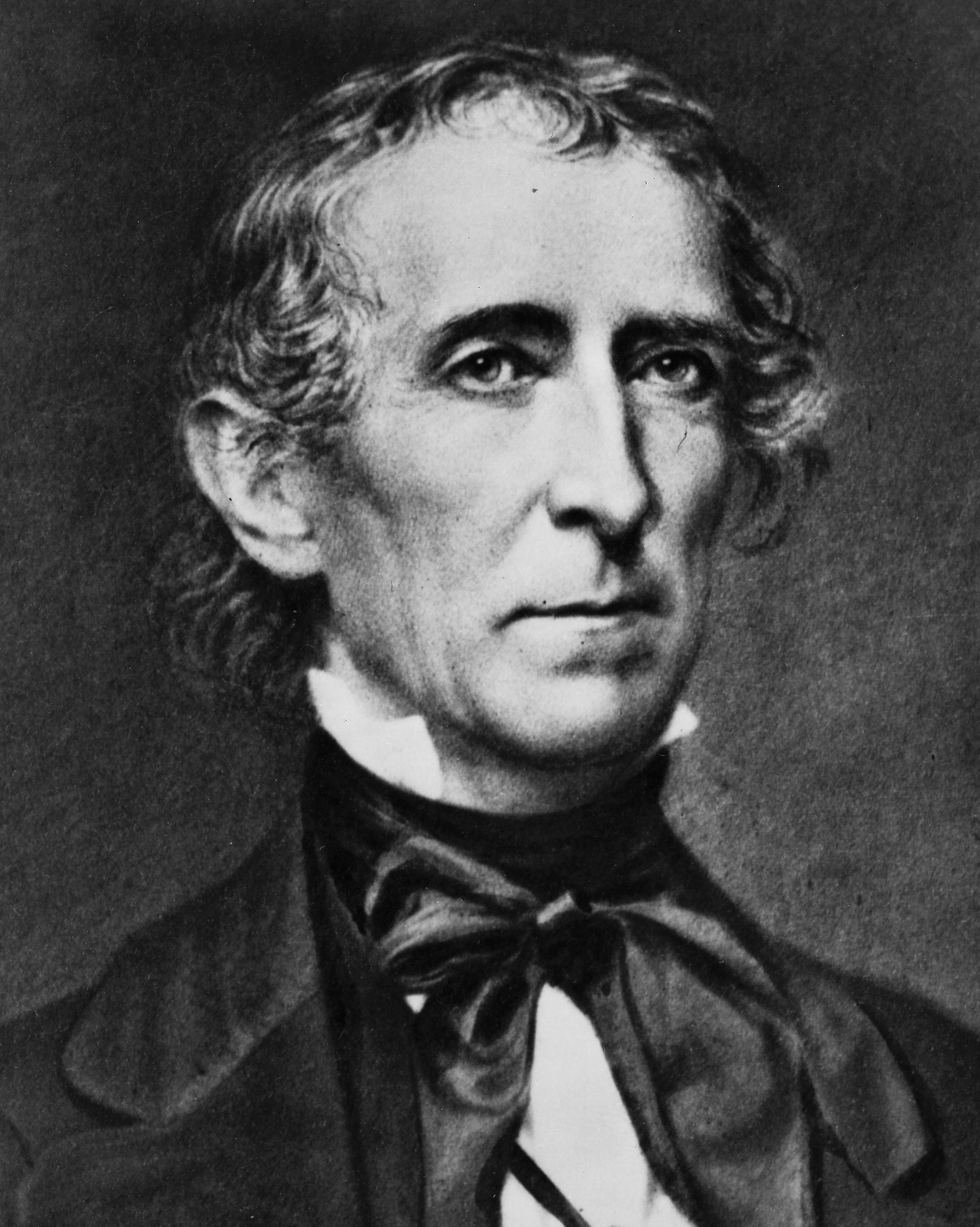

| 18. President John Tyler, Marble Bust, Senate Chamber | |

Although he had served as President of the United States, John Tyler headed the committee that negotiated the terms for Virginia's entry into the Confederate States of America and helped set the pay rate for CSA military officers. On June 14, 1861 Tyler signed the Ordinance of Secession. One week later the convention unanimously elected him to the Provisional Confederate Congress. Tyler was seated in the Confederate Congress on August 1, 1861, and served until just before his death in 1862. |

|

| West Virginia | |

| 19. John Kenna, Marble Statue, Hall of Columns | |

Lesser known for his participation in the Confederacy than other figures on this list, John Kenna was born in Virginia to a lockmaster and sawmill owner. At 16, he joined the Confederate Army under General Joseph O. Shelby and served in the Iron Brigade, a cavalry force that participated in several major raids into Missouri (Shelby later fled with the brigade to Mexico rather than surrender at the war’s end). Wounded in battle, Kenna returned home to practice law and was admitted to the bar in 1870. He rose from prosecuting attorney of Kanawha County in 1872 to Justice pro tempore of the county circuit in 1875, and to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1876. He was a major proponent of the railroad, and in 1883 was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he became Democratic minority leader. His marble statue was donated to the National Statuary Collection by West Virginia in 1901. |