At 10:24 on the morning of June 4, 1942, the Japanese seemed to have won the Battle of Midway—and with it the Pacific war. By 10:30 things were different

-

February 1963

Volume14Issue2

One of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s great services to history was the appointment, in 1942, of the eminent Harvard professor Samuel Eliot Morison to write the story of the United States Navy in World War II. This was to prove no ordinary task of scholarship, for Morison was given the opportunity to witness at sea much of the combat he would one day describe. The result of this firsthand experience, and the decade and a half of research and writing that followed, was the monumental fifteen-volume History of United States Naval Operations in World War II .

Now Admiral Morison has prepared a one-volume distillation of the longer work, entitled The Two-Ocean War , which will be published this spring by Little, Brown. From it we take here his account of an event that was, like Stalingrad, El Alamein, and D-Day, one of the turning points of the war.

In modern times, no record of conquest can quite equal the Japanese sweep across the Pacific in the early months of 1942. Then, with victory apparently in their grasp, they embarked on a plan full of menace for America. It would be a two-pronged effort. One offensive spearhead would push southward, gaining control over the Coral Sea and the islands that lay along Australia’s eastern flank, thus isolating her. Meanwhile the Japanese Combined Fleet, commanded by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, would cross the Pacific to “annihilate” the United States Pacific Fleet. The Japanese striking force would also capture and occupy the Western Aleutians and Midway Island, and then set up a so-called “ribbon defense” anchored at Attu, Midway, Wake, and the Marshall and Gilbert islands.

“The one really sound part of this grandiose plan,” Admiral Morison writes, ”…was Admiral Yamamoto’s challenge to the Pacific Fleet. He knew that the destruction of the Fleet must be completed before 1943, when American war production would make it too late. With the Pacific Fleet wiped out … Americans would tire of a futile war and negotiate a peace which would leave Japan master of the Pacific. Such was the plan and the confident expectation of the war lords in Tokyo.”

Early in May, the Japanese received their first real check when they were turned back in the Battle of Coral Sea. But undaunted by this momentary failure, they now turned their attention to the Midway operation. As Yamamoto’s armada steamed out of its home ports late in May, the chances of an overwhelming victory seemed bright indeed.

—The Editors

Even before the sea warriors of Japan began roaring into the Coral Sea, word had reached the Commander in Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, at Pearl Harbor, of a second offensive that threatened to be much more powerful and dangerous. Imperial General Headquarters issued the order that put the wheels in motion on 5 May 1942: “Commander in Chief Combined Fleet will, in co-operation with the Army, invade and occupy strategic points in the Western Aleutians and Midway Island.” The objectives were three-fold. The named islands were wanted as anchors in the new “ribbon defense,” and Midway also as a base for air raids on Pearl Harbor. But most of all, the Combined Fleet’s commander, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, intended this operation to draw out and “annihilate” the United States Pacific Fleet, in its hour of greatest weakness, before new construction could replace the losses of Pearl Harbor. The success of this battle was central to the entire Japanese strategic concept of the war. Had Japan won, Port Moresby, the Fijis, anything else she wanted, would have fallen into her lap. But the yet small Pacific Fleet declined to accept the sacrificial role.

Midway, situated 1,136 miles west-northwest of Pearl Harbor, is the outermost link of the Hawaiian chain. The entire atoll is but six miles in diameter. Only two islets, Sand and Eastern, the first less than two miles long and the other a little more than one, are dry land. It had been a Pan American Airways base since 1935, and a Naval Air Station since August, 1941.

A comparison of the Combined Fleet thrown into this operation with what Admiral Nimitz could collect to withstand it indicates that Yamamoto’s expectations of “annihilation” were justified. He commanded (1) an Advance Force of sixteen submarines; (2) Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s Pearl Harbor Striking Force, with four big carriers; (3) a Midway Occupation Force, some 5,000 men in twelve transports, protected by two battleships, six heavy cruisers, and numerous destroyers; (4) a Main Body under Yamamoto’s immediate command, comprising Japan’s three most modern battleships and four older ones, with a light carrier; and (5) the Northern Area Force, with three light carriers, two heavy cruisers, and four big transports, for the bombing of Dutch Harbor and occupation of Adak, Attu, and Kiska in the Aleutians. This added up to 162 warships and auxiliaries, not counting small patrol craft and the like—practically the entire fighting Japanese Navy. The total number that Admiral Nimitz could scrape together was seventy-six, of which one third belonged to the North Pacific Force and never got into the battle.

Nevertheless, Nimitz had certain assets which helped tip the scale. The senior commander of the Carrier Striking Force which did most of the fighting was Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher in Yorktown, “the Waltzing Matilda of the Pacific Fleet,” as the sailors called her. Badly damaged in the Coral Sea action, she had been repaired at Pearl Harbor in two days, when by peacetime methods the job would have taken ninety. Fletcher had learned a thing or two at the Coral Sea. Junior to him, and in temporary command of Halsey’s Task Force 16, which had pulled off the Tokyo strike, was Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. (Admiral Halsey had been hospitalized after the Tokyo strike.) Spruance, though not a flyer, showed in the forthcoming battle the very highest quality of tactical wisdom, the power to seize opportunities. “Big E” ( Enterprise ) and Hornet , the carriers under him, had two superlative commanding officers, Captains George D. Murray and Marc A. Mitscher. In Midway itself, where thirty-two Navy Catalinas and six of the new torpedo-bombing Avengers, fifty-four Marine Corps planes, and twenty-three Army Air Force planes (nineteen of them B-17’s) were based, we had an “unsinkable aircraft carrier.” Finally, Nimitz had the inestimable advantage of knowing when and where the enemy intended to attack. But for early and abundant decrypted intelligence, and, what was more important, the prompt piecing together of these bits and scraps to make a pattern, “David”—the United States Navy—could never have coped with the Japanese “Goliath.”

Admiral Nimitz had ordered Fletcher and Spruance to “inflict maximum damage on enemy by employing strong attrition tactics,” which meant air strikes on enemy ships. He cannily ordered them to take initial positions to the northeastward of Midway, beyond search range of the approaching enemy, anticipating that the 700-mile searches by Midway-based planes would locate the Japanese carriers first. To this he added a special Letter of Instruction: “In carrying out the task assigned … you will be governed by the principle of calculated risk … the avoidance of exposure of your force to attack by superior enemy forces without good prospect of inflicting … greater damage on the enemy.” No commander in chief’s instructions were ever more faithfully and intelligently carried out.

Yamamoto really threw away his chance of a smashing victory by dividing his mammoth forces several ways, and by fitting his operation plan to what he assumed the Americans would do. Dividing forces was a fixed strategic idea with the Japanese. They loved diversionary tactics—fleets popping up at odd places to confuse the enemy and pull him oft base. Their pattern for decisive battle was the same at sea as on land—lure the enemy into an unfavorable tactical situation, cut oft his retreat, drive in his flanks, and then concentrate for the kill. Their manual for carrier force commanders even invoked the examples of Hannibal at Cannae and Ludendorff at Tannenberg to justify such naval strategy as Yamamoto tried at Midway. Thus, the preliminary air strike on Dutch Harbor, set for 3 June, was a gambit to pull the Pacific Fleet up north where it could not interfere with the occupation of Midway Island, due to take place at dawn 6 June. When the Pacific Fleet hastened south after a fruitless run up north, which could not be earlier than 7 June, Japanese carrier planes and Midway-based aircraft would intensively bomb the American ships. These, if they did not promptly sink, would be dispatched by gunfire from Yamamoto’s battleships and heavy cruisers.

So very, very neat! But IVimitz, instead of falling for this trap, had three carriers already covering Midway as Nagumo’s carriers approached it. It was the “Nips” who were nipped.

The Japanese Aleutian prong struck first, on 3 June, with the triple object of deceiving Admiral Nimitz into the belief that this was the main show, destroying American installations at Dutch Harbor, and covering an occupation of the Western Aleutians. Besides separate occupation forces, Vice Admiral Hosogaya had light carriers Ryujo and Junyo , three heavy cruisers, and a suitable number of destroyers and oilers. On our side, we had the North Pacific Force commanded by Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald in light cruiser Nashville , with sister ships St. Louis and Honolulu , two heavy cruisers, a destroyer division, a nine-destroyer striking group, six S-class submarines, and a flock of Coast Guard cutters and other small craft. Nimitz’s Intelligence smoked out Japanese intentions in this quarter, and informed the Admiral of them on 28 May, but “Fuzzy” Theobald, as usual, thought he knew better—that the enemy was going to seize Dutch Harbor. Consequently he deployed the main body of his force about 400 miles south of Kodiak, instead of trying to break up the Western Aleutians invasion force. This bad guess lost him all opportunity to fight; for Hosogaya’s two light carriers, under the tactical command of Rear Admiral Kakuji Kakuta, slipped in between Theobald’s force and the land, began bombing Dutch Harbor at 0800 June 3, and returned through a fog mull for another whack at this Eastern Aleutians base next day, completely unmolested from the sea. The Japanese could have landed at Dutch Harbor, for all the protection it had from Theobald. Considerable damage was inflicted on this base, but it was far from being knocked out.

On 7 June undefended Attu and Kiska in the Western Aleutians were occupied by the Japanese according to plan, but Adak was not taken, because it seemed to be too near Unmak. Army P-40’s based on the new Army Air Force field at Unmak had given Kakuta’s carrier planes quite a run for their money.

Turning now to the main show, Old Man Weather seemed determined to help the Japanese. Admiral Nagumo’s Striking Force, built around carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu , and Soryu , veterans of Pearl Harbor, advanced toward Midway under heavy cloud cover; they could even hear the island-based search planes buzzing overhead, but themselves were not seen. The force allotted to occupy Midway was, however, sighted by a Catalina on 3 June. Captain Cyril T. Simard’s island-based air force reacted quickly, though ineffectively. It made but one hit, on an oiler, at 0143 June 4. That was the first blow in this battle south of the Aleutians.

All night 3–4 June the two opposing carrier forces were approaching each other on courses which, if maintained, would have crossed a few miles north of Midway Island. Day began to break around 0400. ft was still overcast over the Japanese, clear over the Americans. A light wind blew from the southeast, another break for the Japanese, since wind is almost as important for aircraft carriers as for the old frigates. Contrary to what was desirable in the sailing navy—to get the weather gauge of your enemy—the lee gauge was now wanted, because a carrier has to steam into the wind to launch or recover planes. Thus, Fletcher and Spruance, having the weather gauge, had to lose mileage during flight operations. Yorktown , having to recover a search mission, had to lag behind when the big news arrived, shortly after 0600 June 4.

This news was a Midway-based PBY’s contact report of two Japanese carriers, headed southeast. For four hours this was all the information that Fletcher and Spruance had of Nagumo’s location and course; but it was enough. Fletcher promptly ordered Spruance, with Enterprise and Hornet , to “proceed southwesterly and attack enemy carriers when definitely located,” promising to follow as soon as his search planes were recovered. Both admirals knew very well that Nagumo’s Striking Force was Yamamoto’s jugular vein, and that their only hope was to cut it.

Ten minutes after Fletcher issued that pregnant order, the next phase of the Battle of Midway opened, over the island itself. One hundred and eight Japanese planes, divided evenly between fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo-bombers, took off from the four carriers before sunrise. Midway search radar picked them up ninety-three miles away, and every fighter on the island was scrambled to intercept; but they were too few, and the Marine Corps “Buffaloes” too weak and slow, to stop the Japanese. The bombing of Midway began at 0630 and continued for twenty minutes. It did considerable ground damage, without breaking up the runways; and Midway antiaircraft fire was very good. Between that and the Marine fighters, fifteen of which were lost, about one third of the Japanese attack group was shot down or badly damaged. In the meantime, four waves of American Midway-based bombers had flown oil to counterattack Nagumo’s carriers. They, too, lost heavily; but, as we shall see, their sacrifice was not in vain.

Now came the most decisive moment in a battle filled with drama. Admiral Nagumo, when sending oft that 108-plane strike on Midway, reserved ninety-three aircraft armed with bombs and torpedoes to deal with enemy ships, it” he could find any. Usually the Japanese were smarter than we in air search, but this time they failed, largely because, according to the Japanese plan, no American carriers should have been around for a couple of days. So Nagumo sent only a few cruiser float planes on routine search, and by 0700 they had found nothing. At that moment Lieutenant Tomonaga, commander of what was left of the 108-plane strike then returning to their carriers, signaled to Nagumo that Midway needed another pounding. Immediately after, there came in on the Japanese carriers the first Midway-based bombing attack, which seemed to second Tomonaga’s motion—obviously Midway had plenty of bite left. So the Admiral “broke the spot,” ∗Prior to take-off, carrier planes would normally be parked or “spotted” on the flight jerk aft. The spot would have to be broken—that is, the planes moved out of the way—when other planes came in over the stern to land.— Ed. and ordered the ninety-three planes struck below to be rearmed with incendiary and fragmentation bombs for use against the island. Fifteen minutes elapsed, and the Admiral was dumfounded to receive a search plane’s report of “ten enemy ships” to the northeast, where no American ships were supposed to be. What to do? Nagumo mulled it over for another quarter-hour, cancelled the former change-bomb plan, and ordered the ninety-three planes again rearmed and readied to attack ships. That took time, and it was already too late to fly those planes off to attack enemy ships, because flight decks had to be kept clear to receive the rest of the Japanese aircraft which had been bombing Midway.

At 0835, when the returning bombers began landing on the Japanese carriers, American birds carrying death and destruction were already winging their way from Enterprise and Hornet . Spruance had taken over from Halsey, as chief of staff, Captain Miles Browning, one of the most irascible and unstable officers ever to earn a fourth stripe, but a man with a slide-rule brain. Browning figured out that Nagumo would order a second strike on Midway, that he would continue steaming toward the island, and that the golden opportunity to hit his carriers would arrive when they were refueling planes for this second strike. Spruance accepted these estimates and made the tough decision to launch at 0700, when about 175 miles from the enemy’s calculated position, instead of continuing for another two hours in order to diminish the distance. Spruance also decided to make this an all-out attack—a full deckload of twenty Wildcat fighters, sixty-seven Dauntless dive-bombers, and twenty-nine Devastator torpedo-bombers—and it took an hour to get all these airborne. Fletcher properly decided to delay launching from Yorktown , in case more targets were discovered; but by 0906 his six fighters, seventeen SBD’s, and twelve TBD’s were also in the air.

Imagine, if you will, the tense, crisp briefing in the ready-room; the warming-up of planes which the devoted ground crews have been checking, arming, fueling, and servicing; the ritual of the take-off, as precise and ordered as a ballet; planes swooping in graceful curves over the ships while the group assembles. This Fourth of June was a cool, beautiful day; pilots at 19,000 feet could see all around a circle of fifty miles’ radius. Only a few fluffy cumulus clouds were between them and an ocean that looked like a dish of wrinkled blue Persian porcelain. It was a long flight (and, alas, for so many brave young men, a last flight) over the superb ocean. Try to imagine how they felt at first sight of enemy flattops and their wriggling screen, with wakes like the tails of white horses; the sudden catch at their hearts when the black puffs of antiaircraft bursts came nearer and nearer, then the dreaded Zekes of Japanese combat air patrol swooping down out of the central blue; and finally, the tight, incredibly swift attack, when a pilot forgets everything but the target so rapidly enlarging, and the desperate necessity of choosing the exact tenth of a second to release and pull out.

While these bright ministers of death were on their way, Nagumo’s Striking Force continued to steam toward Midway for over an hour, as Miles Browning had calculated. The four carriers were grouped in a box-like formation in the center of a screen of two battleships, three cruisers, and eleven destroyers. Every few minutes messages arrived from reconnaissance planes that the enemy was approaching. At 0905, just before the last of the planes returning from Midway were recovered, Nagumo ordered Striking Force to turn ninety degrees left, to course east-northeast, “to contact and destroy the enemy Task Force.” His carriers were in exactly the condition that Spruance and Browning hoped to find them—planes being refueled and rearmed in feverish haste.

Now came a break for Nagumo. His change of course caused the dive-bombers and fighters from Hornet to miss him altogether. Hornet ’s torpedo-bombers, under Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron, sighted his smoke and attacked without fighter cover. The result was a massacre of all fifteen TBD’s. Every single one was shot down by Zekes or antiaircraft fire; only one pilot survived. The torpedo squadron from Enterprise came in next and lost ten out of fourteen; then Yorktown ’s, which lost all but four; and not a single hit for all this sacrifice. No wonder that these torpedo-bombers, misnamed Devastators, were struck off the Navy’s list of combat planes.

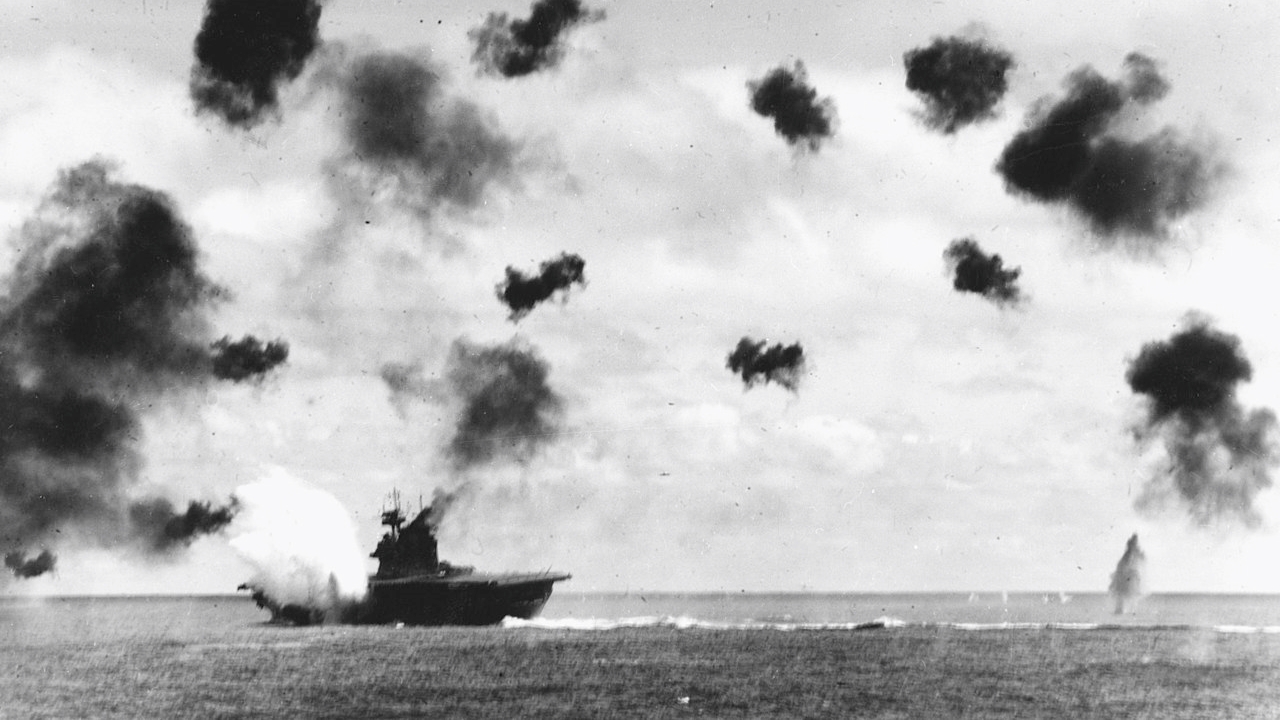

The third torpedo attack was over by 1024, and for about too seconds the Japanese were certain they had won the Battle of Midway, and the war. This was their high tide of victory. Then, a few seconds before 1026, with dramatic suddenness, there came a complete reversal of fortune, wrought by the Dauntless dive-bombers, the SBD’s, the most successful and beloved by aviators of all our carrier types during the war. Lieutenant Commander Clarence W. McClusky, air group commander of Enterprise , had two squadrons of SBD’s under him: thirty-seven units. He ordered one to follow him in attacking carrier Kaga , while the other, under Lieutenant W. E. Gallaher, pounced on Akagi , Nagumo’s flagship. Their coming in so soon after the last torpedo-bombing attack meant that the Zekes were still close to the water after shooting down TBD’s, and had no time to climb. At 14,000 feet the American dive-bombers tipped over and swooped screaming down for the kill. Akagi took a bomb which exploded in the hangar, detonating torpedo storage, then another which exploded amid planes changing their armament on the flight deck—just as Browning had calculated. Fires swept the flagship, Admiral Nagumo and staff transferred to cruiser Nagara , and the carrier was abandoned and sunk by a destroyer’s torpedo. Four bomb hits on Kaga killed everyone on the bridge and set her burning from stem to stern. Abandoned by all but a small damage-control crew, she was racked by an internal explosion that evening, and sank hissing into a 2,600-fathom deep.

The third carrier was the victim of Yorktown ’s dive-bombers, under Lieutenant Commander Maxwell F. Leslie, who by cutting corners managed to make up for a late start. His seventeen SBD’s jumped Soryu just as she was turning into the wind to launch planes, and planted three half-ton bombs in the midst of the spot. Within twenty minutes she had to be abandoned. U.S. submarine Nautilus , prowling about looking for targets, pumped three torpedoes into her, the gasoline storage exploded, whipsawing the carrier, and down she went in two sections.

At 1024 Japan had been on top; six minutes later on that bright June morning, three of her big carriers were on their flaming way to death. But Nagumo did not give up. He ordered Hiryu , the one undamaged carrier, to strike Yorktown. Hiryu ’s two attack groups comprised eighteen dive-bombers, ten torpedo-bombers, and twelve fighters. Most of them were shot down by air patrols and antiaircraft fire, but three Vals of the first strike made as many bomb hits, and four Kates, breaking low through a heavy curtain of fire, got two torpedoes into Yorktown at 1445. These severed all power connections and caused her to list twenty-six degrees. Fifteen minutes later Captain Elliott Buckmaster, thinking that his big carrier was about to capsize, ordered Abandon Ship. Yorktown ’s watertight integrity had been impaired in the Coral Sea battle, and her repairs were so hasty that he feared she would turn turtle.

Admiral Fletcher, who shifted his flag to cruiser Astoria after the first attack, had already sent out a search mission to find the fourth Japanese carrier. Almost at the same moment that Yorktown was torpedoed, these planes found Hiryu . As a result of their contact, “Waltzing Matilda” was revenged just as her dancing career ended. Enterprise , at Spruance’s command, turned into the wind at 1530 and launched an attack group of twenty-four SBD’s, including ten refugees from Yorktown , and veterans of the morning’s battle. Led by the redoubtable Gallaher, they jumped Hiryu and her screen at 1700. The carrier received four hits which did her in, and she took down with her Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, an outstanding flag officer who, it is said, would have been Yamamoto’s successor had he lived.

Yamamoto, who according to plan was keeping well to the rear in his Main Body, built around the mastodonic battleship Yamato , reacted to these events aggressively. He pulled Kakuta’s three light carriers down from the Aleutians, and ordered Vice Admiral Kondo’s heavy cruiser Covering Group to join Main Body next day, intending to renew the battle. He still had overwhelming gunfire and torpedo superiority over anything that Spruance and Fletcher could offer. But, after news arrived that his four splendid carriers were either sunk or burning derelicts, he bowed to the logic of events and at 0255 June 5 ordered a general retirement. He had lost his entire fast carrier group, with their complement of some 250 planes, most of their pilots, and about 2,200 officers and men. In all its long history, the Japanese Navy had never known defeat; no wonder that Yamamoto fell ill and kept close to his cabin during the homeward passage. Never has there been a sharper turn in the fortunes of war than on that June day when McClusky’s and Leslie’s dive-bombers snatched the palm of victory from Nagumo’s masthead, where he had nailed it on 7 December.

The fourth of June—a day that should live forever glorious in our history—decided the Battle of Midway. By destroying the four Japanese carriers and their air groups, the American aviators had extracted the sting from Combined Fleet. Everything that followed now appears to be anticlimax; but the situation during the night of 4–5 June was far from clear to the people at Midway, to Fletcher and Spruance, or, for that matter, to Nimitz and Yamamoto. Spruance knew that the Japanese supporting naval forces, which nobody had yet located, included carriers. With Yorktown disabled, the air groups of his own carriers decimated, and no support in sight, he had to balance the possible damage he could inflict by pressing westward that night, against the risks involved. Consequently he retired Enterprise and Hornet to the eastward, and did not reverse course until midnight. It was fortunate that he refused to tempt fate further; for, had he steered westward that evening, he would have run smack into a heavy concentration of Yamamoto’s battleships and cruisers around midnight and have been forced to fight a night gunfire battle—just what the Japanese wanted.

Prior to ordering a general retirement at 0255 June 5, Yamamoto cancelled a scheduled bombardment of Midway by Admiral Kurita’s four heavy cruisers. Two of these, Mikuma and Mogami , which had sunk Houston and Perth in the Java Sea, were attacked by the bombers Captain Simard had left on Midway—six SBD’s and six old Marine Corps Vindicators. Both cruisers were damaged and Mikuma next day was sunk by dive-bombers from Hornet .

By 1000 June 5 Spruance’s carriers were about fifty miles north of Midway. Five hours later they launched fifty-eight SBD’s to search for targets, but found only one destroyer. After continuing to a point some 400 miles west of Midway, and increasing his score only by the sinking of Mikuma , Spruance turned east on the evening of the sixth to keep a fueling rendezvous.

After the battle was over Yamamoto blamed his defeat on the failure of his advance screen of sixteen submarines to accomplish anything. The fault, however, was the Admiral’s. He had deployed them to catch the Pacific Fleet where he counted on its being, instead of where it was. Nevertheless, a Parthian shot by one of these boats scored for Japan in the last play of this big game. Her victim was Yorktown , abandoned after her hits on 4 June unnecessarily, as proved by the fact that she floated for twenty-four hours with no human hand to help. She was taken in tow on the fifth by minesweeper Vireo , too small to cope with the carrier’s 19,800-ton bulk. As Yorktown inched along toward home on 6 June, submarine I-168 penetrated her destroyer screen and got her torpedoes home. A third torpedo sank destroyer Hammann , which was secured to the carrier to furnish power and pumps for the salvage crew; she went down in four minutes, taking eighty-one officers and men with her. The two other torpedo hits finished old “Waltzing Matilda.” During the night her list suddenly increased, and at dawn it was evident she was doomed. The escorting destroyers half-masted their colors, all hands came to attention, and at 0600, with her loose gear making a horrible death rattle, Yorktown rolled over and sank in a two-thousand-fathom deep.

Midway was a victory not only of courage, determination, and excellent bombing technique, but of intelligence, bravely and wisely applied. “Had we lacked early information of the Japanese movements, and had we been caught with carrier forces dispersed, … the Battle of Midway would have ended differently,” commented Admiral Nimitz. So, too, it might have ended differently but for the chance which gave Spruance command over two of the three flattops. Fletcher did well, but Spruance’s performance was superb. Calm, collected, decisive, yet receptive to advice; keeping in his mind the picture of widely disparate forces, yet boldly seizing every opening, Raymond A. Spruance emerged from this battle one of the greatest admirals in American naval history.

The Japanese knew very well that they were beaten. Midway thrust the war lords back on their heels, caused their ambitious plans for the conquest of Port Moresby, Fiji, New Caledonia, and Samoa to be cancelled, and forced on them an unexpected and unwelcome defensive role. The word went out from Imperial Headquarters that the name Midway was not to be mentioned.

Admirals Nimitz, Fletcher, and Spruance are, as I write, very much alive; Captain Mitscher of Hornet , Captain Murray of Enterprise , and Captain Miles Browning of the slide-rule mind have joined the three-score young aviators who met flaming death that day, reversing the verdict of battle. Think of them, reader, every fourth of June. They and their comrades who survived changed the whole course of the Pacific war.