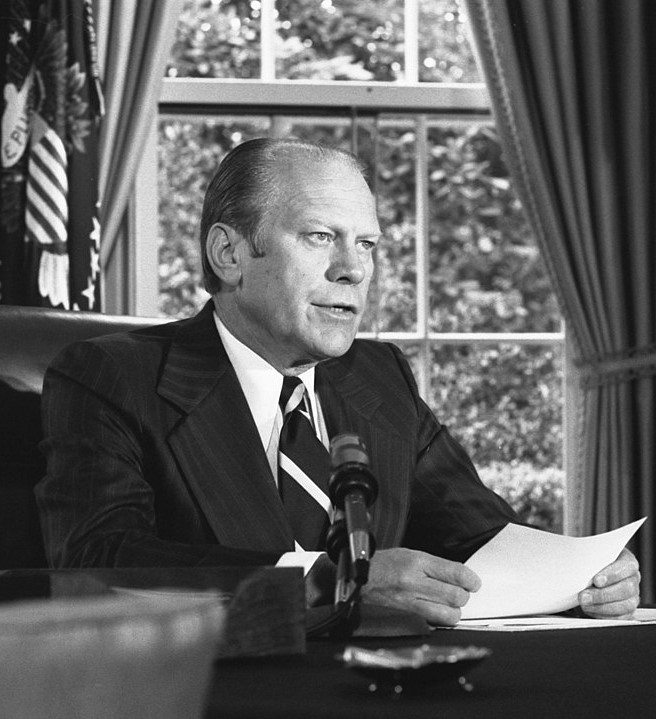

Though he defended his decision as being in the nation's best interest, Ford's pardon of his predecessor may have contributed to his short-lived presidency.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

Gerald R. Ford, Jr., Republican Congressman from Michigan and House Minority Leader, became Vice President to Richard M. Nixon under the provisions of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment when, in 1973, Spiro T. Agnew resigned the vice presidency after pleading guilty to tax evasion. Upon Nixon's own resignation from the presidency, Ford became President. He thus served as both Vice President (selected by Nixon and confirmed in that office by Congress) and President without having been elected to either office — an unprecedented distinction.

Besides having to assume a presidents normal responsibilities upon Nixon's resignation, Ford faced the additional challenge of overcoming the consequences of the Nixon administration's corruption, clearing the political atmosphere of the bitter controversies of Watergate, and restoring Americans' confidence in their government. No significant misconduct marred his presidency, which proved to be — because of Ford's failure to be elected in 1976 to a full term — a short one.

After Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, Ford sought to decide whether to pardon the disgraced former President, a decision forced upon him by powerful Republicans and Nixon supporters and his own desire to return the nation's governance to normality. Ford's situation was complicated by the fact that his constitutional authority lacked the backing of the nation's voters. Accordingly, he had to act judiciously. He also realized that, without a pardon, his administration might be consumed in responding to a prosecution and trial of his predecessor, which would have contributed to more national divisiveness and prevented him from concentrating on other domestic and foreign policy problems, including his chances of election to the presidency in his own right in 1976.

Consequently, after thirty-one days as President, on September 8, 1974, Ford unconditionally granted Nixon “a full, free, and absolute pardon ... for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in” while in office. Because Nixon had been named only as a co-conspirator in charges brought against others in the Watergate scandal without having been indicted for any of them, he was thus freed from the threat of all criminal charges growing from his presidency.

Ford maintained that his pardon of the former President was in the nation's best interests. Although the pardon raised suspicions that a “deal” had been struck between the two men in the last days before Nixon's resignation — or even, it was rumored, as early as eight months before, when Ford succeeded Agnew as Vice President — no evidence has ever emerged to confirm this suspicion, and historians now absolve Ford of the charge.

The only known political agreement between Nixon and Ford was the latter's 1973 concession not to seek the presidency in 1976 because Nixon hoped that John B. Connally, Jr., former Democratic Texas Governor and Secretary of the Treasury under Nixon, and by 1973 a Republican, would succeed him.

Yet Ford's action could not escape controversy as unwise and part of a “corrupt bargain,” and his press secretary, Jerald F. terHorst, resigned in protest over it. The consensus among historians is that while his pardon of Nixon weighed on Ford's chances of winning the 1976 election, it was among many factors contributing to his loss.

Copyright © 2019 by The New Press. Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.