The blind guitarist and singer from Deep Gap, North Carolina transformed American music by blending bluegrass, folk, country, blues, and gospel.

-

September 2022

Volume67Issue4

One afternoon in 1960, Ralph Rinzler, a mandolin player and folklorist from Passaic, New Jersey was visiting the Old Time Fiddler’s Convention in an isolated part of northwestern North Carolina called Union Grove. Ralph was looking for the real thing – unadulterated hillbilly music in a place so remote even today that it’s identified as a “non-functioning county subdivision.”

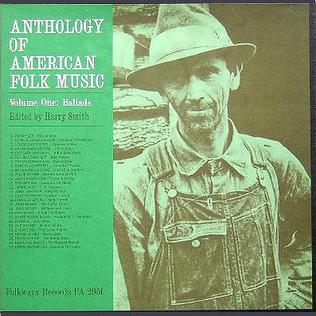

As Ralph was scoping out the scene, he heard a man playing clawhammer banjo and singing. It was the famous Tennessean, Clarence Ashley, who’d performed at Appalachian medicine shows as a teenager, made his first record in 1928 with the Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers, and then, in the early 50s, drawn the attention of musicologists in the Northeast like Rinzler when some of his tunes appeared on the classic three-album collection, Anthology of American Folk Music.

Ashley had perfect credentials, from the perspective of urban Yankee folk fanatics like Ralph Rinzler: He’d been a coal miner during the Depression.

Ralph decided to return to the region soon to record Ashley at his home in Shouns, Mountain City, Tennessee – a place with the middling distinction that Daniel Boone had passed through there for one reason or another in 1761.

At the session in Mountain City, Clarence Ashley was accompanied by a blind electric guitar player named Arthel Watson from Deep Gap in the Blue Ridge mountains of North Carolina. Being a purist, Rinzler was only interested in old-timey players on wooden instruments, with no amplification. He wouldn’t record Doc.

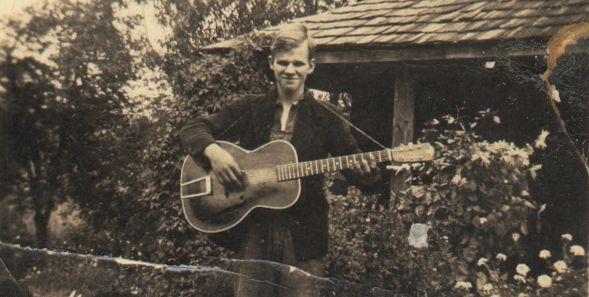

A single day can change everything. It did in this case. Ralph was sitting in the back of a pick-up truck with some guys in Ashley’s band, including Arthel. One of them was playing a banjo. At a stop along the road, Watson said “Let me see that banjo, son!” He started picking, and Ralph was stunned to see an electric guitarist playing “the hell out of” Appalachian mountain music.

Rinzler befriended Arthel and decided to promote him at Greenwich Village clubs like Gerde’s and the Gaslight and the Ash Grove in L.A. It was the same time that Bob Dylan had arrived in New York City from Minnesota, mimicking Woody Guthrie and never touching an electric guitar. What an ironic gem that Watson had begun professionally as an electric guitarist and was persuaded by a Jewish enthusiast from New Jersey to go acoustic, while Bob Dylan, within four years, would be excoriated as a Judas for going electric.

Folk fans in America’s big cities were thrilled by Doc’s blazingly clean flatpicking solos, and they loved his warm baritone voice. He became a star in 1963, with Rinzler as his manager, because of his performance at the Newport Folk Festival. The following year, he released his first album, Doc Watson. (His nickname had been created when a radio DJ during a live broadcast in 1941 said that Arthel might not be a great name for an artist, so a woman in the audience shouted “Call him Doc!”).

That debut record would become a classic, with pieces adapted from banjo and fiddle tunes and music ranging from blues to hillbilly music, spirituals, and ragtime, from the woebegone hymn “Talk About Suffering” to the ironic “Born About Six Thousand Years Ago,” in which he sings “I saw old king pharoah’s daughter find little Moses on the water, and I can whip the man who says it isn’t so.”

His talking-style singing often made listeners feel like they were sitting on a porch with him as he performed one of the hundreds of tunes in his repertoire. “St. James Hospital” is Doc’s version of a British ballad called “The Unfortunate Rake” from the late 1700s about a soldier who wastes his salary and his health on hookers. By the 1920s, a version of this song called “St. James Infirmary Blues” (or “Gambler’s Blues”) was published in America, and variations of it were recorded by Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and Jimmy Rodgers.

Doc’s 1964 adaptation features some of his most beautiful, hypnotic, harp-like picking and melancholy vocals about a dissolute, dying cowboy: “… for my poor head is aching and my sad heart is breaking. I’m a poor cowboy and Hell is my doom.” Doc once told an interviewer: “When I play a song, be it on the guitar or banjo, I live that song, whether it is a happy song or a sad song ...” Doc was authentic, and his fans were likely to not only love his music, but the man.

Though he had started as a fingerstyle guitarist and banjo player, he switched in the early 60s to mainly flatpicking – using a single pick, and he developed an instrumental and vocal sound that young Americans in big cities found more affecting than what most other white Southern performers were doing. Chet Atkins, Merle Travis, and Lester Flatt may have been technically superior players, but none of them developed the dedicated fan base outside of the South that Doc achieved. This was due to a combination of factors: his ranging across genres, his especially warm, rich vocalizing and clean picking, his absolute lack of artifice on stage, and his blindness – a vulnerability which he never exploited, but which made all the blues and ballads he played especially moving.

Doc had lost his sight before he was two as the result of an untreated ear infection. Traveling alone was extremely difficult for such people back then. In 1964, his son Merle joined him as a fellow guitarist. They played for 20 years together, Doc gaining acclaim as a living encyclopedia of American music, including comical tunes like “Intoxicated Rat,” “Tennessee Stud,” and “Froggy Went A-Courtin,” a Scottish nursery rhyme dating back to 1549. Merle was a gifted player with an affinity for the blues and the slide. They had two great decades together, and then tragedy struck.

In 1985 on his farm in Lenoir, North Carolina, 36-year-old Merle was driving his tractor down a steep hill when his brakes locked and the harvester rolled over. He got crushed under it, killed right away. Doc and his wife were deep in misery. This is what the father said: “I didn’t just lose a good son. I lost the best friend I’ll ever have in this world.” He stopped playing for a while, but eventually was convinced to come back. He carried on. Kept traveling around America and the world playing his beautiful tunes, until, in his 70’s, he decided to slow down a bit, spend more time with his family in Deep Gap, and focus on performances mostly in the South.

My own connection with Doc began when I was a 16-year-old in North Haven, Connecticut. Jimmy Carter, who I'd campaigned for door-to-door in my town, had recently taken office, and I was getting into acoustic guitar music by way of Cat Stevens’ Teaser and the Firecat album, Greg Lake’s “The Sage” and his solo side on ELP’s Works, Volume 1, and Steve Howe’s “Clap,” “Mood for a Day,” and some beautiful passages on Close to the Edge and Tales from Topographic Oceans. I found my way to American roots music partly by being a progressive-rock pothead.

One Saturday, I rode my bike to the best local record store – the Music Box in Hamden. I asked a studious-looking longhair behind the counter to recommend two great acoustic players. He led me down an aisle and showed me two names I’d never heard of: John Fahey and Leo Kottke. I bought an album by each and have been totally hooked now through eight presidencies.

Reading liner notes and talking to older people who knew a lot more than I did, I also learned about Doc Watson, the blind bard from way out in the woods near Fire Scale Mountain in a corner of North Carolina near where it meets Virginia and Tennessee. Being a Yankee, I thought such a place was pure redneck, and I didn’t imagine anything swell coming out of there. I heard they didn’t celebrate Lincoln’s birthday down South.

When I moved to Washington, D.C. in 1979 to study at American University, one of the many delights was the school’s radio station, WAMU, which specialized in bluegrass music. Plenty of Doc Watson. Tunes like “Mississippi Heavy Water Blues,” about a deluge that wrecked the storyteller’s home: “I’m sittin’ here lookin’ at all of this mud, and my good gal washed away in that Mississippi flood.” Doc’s version is more plaintive and pretty than the Barbecue Bob 1928 original. When Doc sings “Mama … mama … your daddy misses you,” his voice breaks and drops as he calls out to her. It’s one of the most desolated passages of any song I’ve ever heard.

Then there’s his version of “Stormy Weather” – real slow, loping along, hopeless as can be, except that the tune is just so pretty, with the fiddle and Merle’s slide playing on a Resonator and Doc’s sonorous voice. Other beauties like “Deep River Blues,” “Summertime,” and “Windy and Warm.” Some perfection came out of the Deep white South, and much of that came from black people and from the churches, from Scots-Irish music, all blended, diffused.

In his 1960 autobiography, Treat It Gentle, the great early-jazz clarinet and sax player, Sidney Bechet, had this to say about white people playing the blues: “I don’t care what you say. It’s awful hard for a man who isn’t black to play a melody that’s come deep out of black people. It’s a question of feeling. Take a number like ‘Livery Stable Blues.’ We’d played that before they could remember; it was something we knew about a long way back. But theirs: It was a burlesque of the blues. There wasn’t nothing serious in it anymore.”

It may be that Bechet had never listened to the 1958 classic LP, Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely. But once Doc Watson’s first album was released in 1964, no one could credibly claim that white people just didn’t have what it takes to perform stirring blues. Seven years later, with tunes such as “Stormy Monday” and “Whipping Post,” the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East album would forever put the lie to Bechet’s claim.

I first got to see Doc play in Los Angeles in 1988 at the Wadsworth Theater next to a. V.A. facility where I often saw woebegone veterans wandering around in a daze. He played a song that night; it had a woman’s name in it, and I never wrote it down, but it was so beautiful that I was tearing up and thinking there could hardly be a better calling than to do what Doc did.

I have been an autograph collector since I was ten, and I had a big desire after the show to meet Doc, talk to him, thank him, and see if getting a signature was possible. But I was just too nervous because I’d never even stood next to a blind person and had no clue how I’d interact with him. I chickened out and regretted that for 15 years.

Then, on January 11, 2003, I drove eight hours, from Torrance in the South Bay area of L.A. to Tucson to see Doc perform at the Berger Performing Arts Center. It was a long haul, but, when I got to the venue, it seemed that there was nowhere else better for me to be. He played with his grandson, Richard (Merle’s boy), then took a break, and played a second set with his longtime stage partner, Jack Lawrence.

It was interesting to see how much of the Doc-Merle genius had passed down to the grandson; Richard was okay, but the special thing was to see Doc up there with his blood, carrying the torch. Truth be told, I didn’t want to see anyone but him, and I easily could’ve sat there for four hours listening to only him.

After the concert ended, I knew I was going to head right for his dressing room. I decided to be brave. So it was to Doc I went, with no idea how shielded he might be by his fellow musicians and auditorium staff. I walked into an offstage area, down a slightly inclined hallway that led to the artists’ room. No one outside it. I glided in, wearing my “I belong here” mask, while half expecting I’d get booted out for trespassing. And there was Doc all by himself, looking, to me, a bit lost, maybe abandoned, but he may just as well have been enjoying some quiet time to himself. Not knowing a damn thing about blind folks, I just assumed things, most of which were probably wrong.

I felt sad for him, sitting there with no way to see, no way to protect himself, no one to talk with, no bearings except for what he can hear and smell and touch. Shouldn’t someone be watching over our American gems? I came with the best of intentions, but what if someone wanted to hurt him? Mark David Chapman got John Lennon’s autograph, and Lennon was nice to him, asking him if there was anything else that forlorn young man wanted. Chapman said no and then shot his former hero in the back. Murdered him as he was walking into his apartment building.

If anyone tries to hurt Doc, I’ll take a bullet for him. This was somewhere in my head as I suddenly came into his presence.

I didn’t know quite what to do, since I was an intruder with an agenda. I wanted to meet him, chat with him, get a guitar pick he had used, and, if I was really lucky, an autograph, assuming he was one of those blind stars who could sign. That’s another thing I had no idea about. Would it be offensive to ask a person without sight to give a signature? Does Stevie Wonder sign? Did Ray Charles? Or might it be offensive not to -- to assume that they can’t or don’t want to do what all other celebrities are expected to do?

Mainly, I was there for me. Just another fan getting into the space of a famous person. Then again, I know that there are a lot of great artists, especially in the jazz world, who like it when sincere fans come up to them to express their appreciation and respect. What to say to Doc Watson, now that I am finally right next to him, all these years after I couldn’t get the courage up to meet him in my own town?

I just walked over to him, sat down in a chair next to him, and gently said: ”Hi, Doc Watson. Sorry to bother you. I’m Keith Fitzgerald and I have loved your music for many years. Thank you so much. I drove all the way from L.A. to see you tonight. You sounded great.” I decided to be honest, speak from the heart, and be sure not to condescend. In other words, to forget about the blindness, to look into his dull-gray eyes, as if he could see me, to communicate face-to-face.

“Well, hello there! Tell me your name again. You’re Keith? Well, it’s nice to meet you, Keith, and thanks for coming. How are you doing?” All the gentleness of the grandfathers I never knew because they had died when I was a real little boy, but I’d often heard about how good they were. And now I am here backstage in Tucson with one of my idols, and he is like my grandpa, full of cheer and he welcomes me, puts me at ease.

I’m in my bliss just being there with him, just Doc and Keith, and he’s teaching me. He is a living history, a bunch of worlds and years and stories and songs and songs and songs and loss and life and death and healing. Endless cities and fans he can’t see, but he can feel us. I want to hug him, but I don’t.

After a while, I ask if I can get a pick that he used. He says: “Well, I have to specially file down my picks to get them the thickness I like. I have to custom-make them for myself and I don’t like to give them away, so I can give you a new one, but you’ll have to wait a wee bit. Richard brought my guitars out to the van already, and I have one in my case. I can get one out of there for you when we leave.”

Oh, yes, I can wait. From the beginning, my desire is to make him feel comfortable. For me, that means avoiding any shallow conversation and not treating him like a handicapped person. It means being natural, even though this situation, for me, is extraordinary, and I will take it with me to my grave.

We talk about where he’s going next, if he plans to go to L.A., stuff like that. However much I love bluegrass and all the other music he plays, I feel that I am not qualified to talk too intelligently about music with such a master.

At a certain point, three other fans find their way into his dressing room, so I go out quickly to retrieve my best friend, who had gone to the bathroom right after the show ended and who I’d briefly forgotten about while I was with Doc. I find her and quickly bring her to where he is. I introduce them; my companion is now nearly in my heaven. Grandson Richard finally returns from wherever he was -- maybe out front in the lobby with Jack Lawrence signing CDs. Two of the other fans -- a couple -- actually ask him for an autograph.

I couldn’t do that. But, since they did, I also ask. I never hesitate to ask for the signature of someone I admire. Doc smiles and says: “Sure, if Richard will help me here.” And then I see one of the cutest, most heartwarming things: Doc holds onto the Sharpie as Richard signs his grandpa’s name. Who cares about the authenticity of it? Who signed my program? Doc did, with his heart. And Richard did it with his hand. This autograph is one of the most special in my collection.

Just after that, he tells Richard that he is going to get a pick for me out of his case when we get to the van. Another fan suddenly says: “Oh, Doc, can I get one, too?” Doc replies: “Now, c’mon. Don’t be greedy. This fellow here asked me for one at the beginning, so I’m gunna give him one.” He isn’t mean at all, but he does draw a line, since the pick request by the other guy was obviously an afterthought. There is a justice in that, though I’m sure glad I’m not the one who’s turned down.

When we get to the van, Doc asks Richard to take his guitar case out for him. Once it is handed to him, he takes care in laying it down carefully and opening it. He consciously turns his back to me so that I can’t quite see what he’s doing as he fishes in his case. He seems to be having trouble locating the pick. Then he stands up, and says: “Well, I can’t seem to find it ... Lemme see ...” And he turns his right side away from me as he reaches in his pants pocket. Then he turns toward me and says: “Here you go; this is all I have.”

What he gives me is the pick he played with that night, custom-shaved to fit him just right. The going into his case and telling me that he didn’t want to give up one of those filed picks was just an act. He had put this kind of deviously sweet, boyish effort into tricking me and then giving me this surprise. It was a ruse performed by a blind saint. He knows I’ll be thrilled with this gift, and he doesn’t want to make it too easy.

We say goodbye to Doc Watson and begin our long journey back to the City of Angels. I hope to see him again, but if I never do, it will be O.K. I have seen him play twice and sat down with him for 20 minutes. There is not a trace of arrogance in him. Just this tenderness that emanates from the stage, the records, The Meeting. I consider that I have lived fully; I am ready.