A longtime expert on Blues music recounts what it was like to work with an artist who defies definition.

-

Spring 2021

Volume66Issue3

Editor's Note: William Ferris is the former Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities and founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

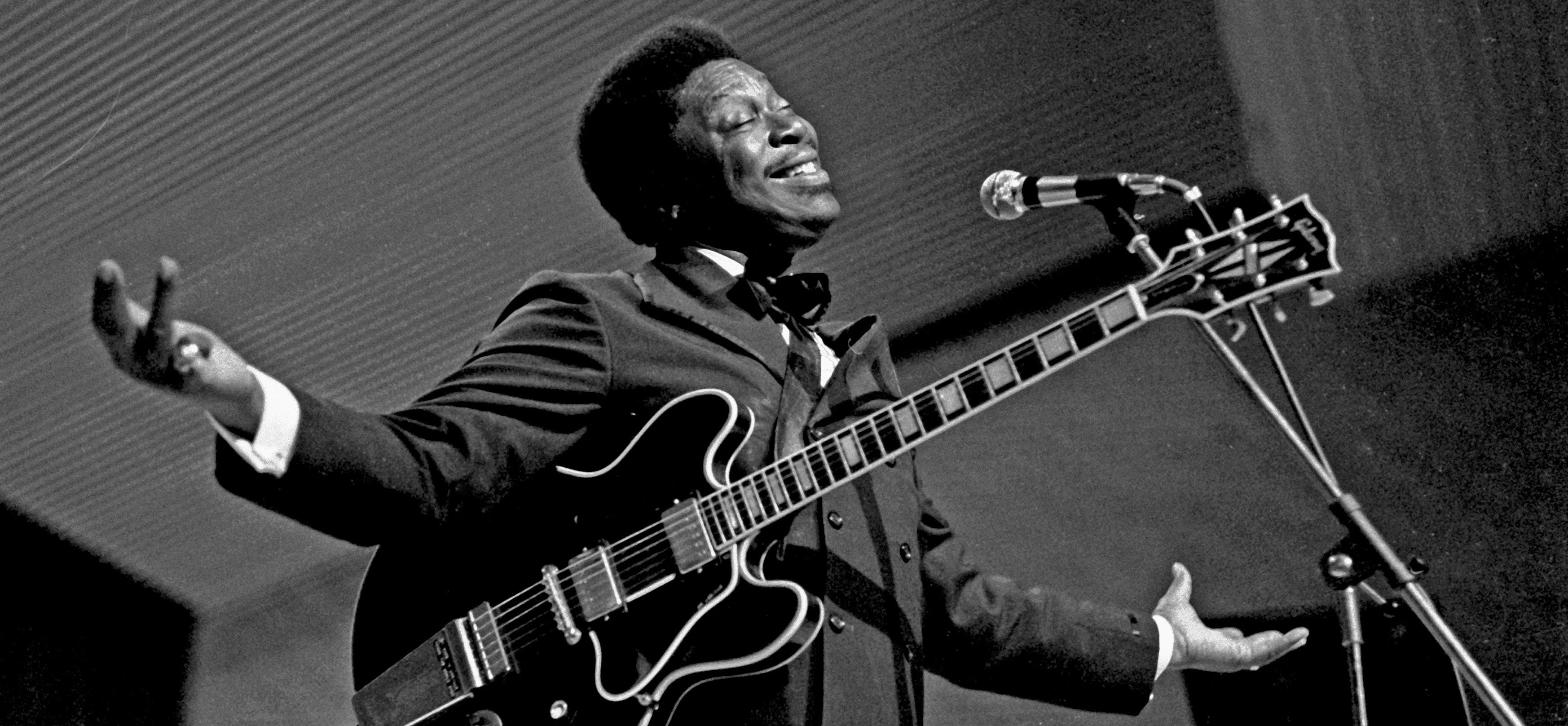

B. B. King’s performances and recordings defined the Blues for more than six decades. King reached out to members of each new generation with music they understood and embraced, and even into his eighties he followed a rigorous schedule of performances throughout the United States and overseas that would exhaust a much younger artist.

I once asked King about how the Blues began, and he told me their origin was a mystery, like the creation of life on the bottom of the ocean. He continued, “The earliest sound of the Blues that I can remember was in the fields, where people would be picking or chopping cotton. Usually one guy would be plowing by himself or take his hoe and chop way out in front of everybody else. You would hear this guy sing…just what he felt at the time. The song would be maybe something like this: ‘Oh, wake up in the morning, about the break of day.’"

As a musician, B. B. King defied definition. Born Riley B. King on September 16, 1925, on a plantation in the Mississippi Delta near the towns of Itta Bena and Indianola, he was influenced by gospel singers in the Black church, as well as by Blues artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson. In 1946 King hitched a ride to Memphis, where he lived with his cousin Bukka White, a noted Blues artist.

King recalled how, “This was the very first time I had been to Memphis, and Memphis was to me then like New York City would be to the average person. I’d never seen a city as large as Memphis. I was really like a kid in a candy store.”

In Memphis King launched his career as the “Pep-ti-kon Boy,” advertising Pep-ti-kon health tonic on radio station WDIA. He also performed with Bobby Bland, Johnny Ace, and Earl Forest in a group called the Beale Streeters. King adopted the nickname the Beale Street Blues Boy, which he shortened to Blues Boy, and then to “B.B.”

In 1950 King’s “Three O’Clock Blues” topped the Rhythm-and-Blues charts for four months and launched his career as a professional musician. He organized his own band and went on the road, barely two years after he made his last cotton crop in the Delta. Thus began a career that he continued uninterrupted into his eighties and underscored the power of his line, “Nightlife is a good life, the only life I know.”

Having grown up without parents, King told me, “That left me at a loss for love.” He found his family through the Blues. “Whenever I would sing and have these people gather round me like they did, they seemed to me as a family — that family that one looks for, one tries to find.”

For twenty years, King played over three hundred one-night stands a year in Black-owned clubs on the “Chitlin Circuit.” He also played weeklong engagements each year in large, urban Black theaters such as the Howard in Washington, the Regal in Chicago, and the Apollo in New York.

As the civil rights movement developed in the early sixties, King’s career fell into a slump. Young Black audiences found his music uncomfortably close to the world of Jim Crow, and white fans of the folk music revival felt he was too commercial. Only when the Rolling Stones, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and British and American rock groups acknowledged King as their idol did his career revive. After his first European tour in 1968, King was embraced by white audiences in the United States, and their support steadily grew over the years.

Unlike many other Blues artists, King blended diverse styles in his music. As a child, he learned to play the Blues on the one-strand-on-the-wall, a traditional instrument made by stretching a wire from a broom handle between two bricks across a metal bolt on each brick. King plucked the string and moved a bottle up and down to change notes.

“Instruments weren’t very plentiful in the area where I grew up,” he recalled to me later. “We felt a need for music, so we would put up a broom wire. Usually we would nail it up on the back porch. In case you’re not familiar, brooms had a kind of straight wire wrapped around the straw that would keep the broom together….We would…take that wire off of it. We would nail it on a board or on the back porch….We would stretch the wire, making it tighter…until it sounded like one string on a guitar.”

B.B.'s guitar style was strongly influenced by Blues guitarists Lonnie Johnson and T-Bone Walker and by jazz guitarists Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian. He blended their styles with delicately “bent” notes and powerful vocals drawn from his musical roots in the Mississippi Delta.

B. B. King’s recording and performing career was truly unique. He issued over seven hundred recordings, received fifteen Gammy Awards, and met presidents, heads of state, and the Pope. A familiar figure on television and in advertisements, he continued to tour and greets fans with warmth and humor.

I first heard King’s music in the 1950s on Nashville radio station WLAC’S late-night blues show sponsored by Randy’s Record Shop, which was hosted by John R. Richbourg, Gene Nobles, and Bill “Hoss” Allen. As a teenager in Vicksburg, I danced to King’s records, along with those of Elvis Presley. The Blues and Rock and Roll were intimate parts of my life during those years.

Our personal friendship began in the 1970s when I taught at Yale University. King generously agreed to visit my class and spoke with my students.

In 1977 the Yale senior class selected King as their commencement speaker, and President Kingman Brewster awarded him an honorary doctorate of humane letters, stating, “In your rendition of the Blues you have taken us beyond entertainment to the deeper message of suffering and endurance that gave rise to the form.”

I did a series of interviews with B. B. King during his visits at Yale University and at his home in New York City. Portions of these interviews are featured in my film Give My Poor Heart Ease.

Since those years at Yale, B. B. King’s friendship blessed my life in more ways than I can count. Our relationship grew in part because of King’s strong belief that the Blues should be an essential part of education at every level. At Yale he met with colleagues like historian John Blassingame and literary scholar Charles Davis, chair of the Afro-American studies program.

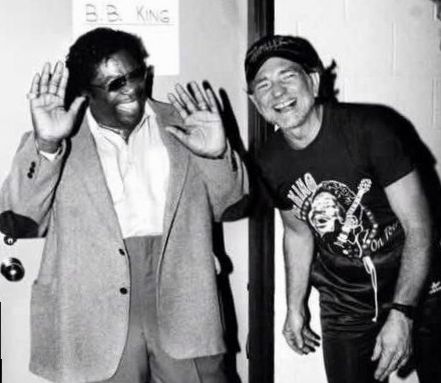

While at Yale, I joined King at concerts in Boston and in Germany. The excitement of his performances and his warmth toward fans who lionized him were memorable. In his pocket, he always carried an ample supply of red plastic guitar picks with “B. B. King” inscribed on them. For Blues pilgrims, these relics were proof of meeting “the King.”

During one of his visits at Yale, we walked around the campus and visited the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. As we approached the entrance, several young boys were playing in the courtyard outside, and I said to them, “Would you like to meet B.B. King?” They replied, “That ain’t no B.B. King.” King reached in his pocket, gave each child a red guitar pick with his name on it, and shook their hands. It was a special moment for all.

In 1979 I moved from Yale University to the University of Mississippi as the first director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture. That fall the center hosted a historic concert by King that he later released as a two-record LP entitled Now Appearing at Ole Miss. King donated the proceeds from the sale of the album to the Red Cross to assist survivors of a flood that had devastated the Mississippi Delta earlier that year.

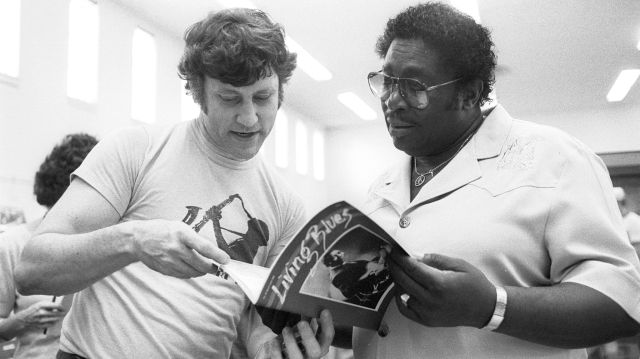

Shortly after his concert, King gave his massive record collection and other memorabilia to the University of Mississippi to help establish its Blues Archive. The B. B. King Blues Collection, the Living Blues Archive — amassed by Jim O’Neal and Amy van Singel — and the Kenneth Goldstein Folklife Collection in the Blues Archive are unique resources for the study of the Blues and southern music. My own library of folklore records and books is also part of the Blues Archive, which continues to grow and to support scholars and students interested in the Blues.

The University of Mississippi Center for the Study of Southern Culture also publishes Living Blues magazine and hosts an annual Blues symposium, both of which were inspired by King and his gift to the Blues Archive.

In 1990 the center organized a “College on the Mississippi” on the Delta Queen that featured B. B. King, Alex Haley, Shelby Foote, Mose Allison, and Eli Evans. During the trip I sat with King in his cabin as he spoke with Shelby Foote about recently released Robert Johnson recordings. Foote grew up in Greenville, Mississippi, and he and King reminisced about their childhoods in the Delta and the importance of the Blues for each of them.

While on the trip King used his laptop computer which was equipped with software that transcribed music that he played on his guitar “Lucille” to help him compose new songs. He proudly reminded me that, “I happen to be a Blues musician that writes music. That’s one of the big differences between King and older Bluesmen. I carry a ten-piece orchestra, and they read music.”

One memorable evening at the W. C. Handy Blues Music Awards in Memphis, I sat backstage with King and Willie Nelson as they recalled their musical careers. At one point, Nelson turned to King and said, “B., I have to admit that I stole a few guitar licks from you over the years,” to which King replied, “And I am proud to know you could use them.”

Through my friendship with B. B. King, I met Sid Seidenberg, his manager for many years. Seidenberg was often present at concerts and events with King, and he played a key role in developing King’s career. In 1969, Seidenberg introduced a polished production that used strings on King’s recording of “The Thrill is Gone,” which reached number three on Billboard and became his signature song. I first heard the song when I was being processed out of the army as a conscientious objector in 1970, the Vietnam War was raging, and the song captured my spirit in the deepest way.

In 1999, while I served as Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the NEH gave King a humanities award. The award was presented in the Old Post Office, where King spoke to the staff and sang several of his best-known Blues songs. My interview with King during the ceremony was published with a cover photo of King in the May-June 2000 issue of Humanities Magazine. It was a special honor that King allowed the NEH to feature his interview and photograph in the magazine, and the response to the issue was overwhelming. I also joined King when he spoke and performed in the White House while President Bill Clinton was in office.

In 2000 King and I appeared together at the Smithsonian Institution’s tribute to King’s life and music as part of its millennium celebration. When King learned that John Hope Franklin was in the hall celebrating his birthday, he and his guitar Lucille led the audience as they sang a memorable “Happy Birthday” to Franklin.

Throughout his impressive career, King has honored his home state of Mississippi and his hometown of Indianola. Each year in June, he visited the state for two weeks, and he gave benefit concerts at Parchman Penitentiary, the Medgar Evers Homecoming Festival, and the B. B. King Blues Festival. The B. B. King Blues Museum opened in 2008 in Indianola and its moving displays honor King’s home in the Mississippi Delta and his historic role in shaping the Blues. He was buried beside the museum in 2015.

When I asked King to define the Blues, he replied, “The Blues are the three Ls, and that would be living, loving, and, hopefully, laughing—in other words, the regular old E formation on the guitar with the regular three changes. The Blues are really life to me because all my friends, everything around me, the music that I hear, everything leads me back to the feeling of the Blues, or the feeling that I get from playing or singing. In fact, everything that I’m connected with—life itself—is the Blues. If I had to try and play the way I feel about it, it would be something like this [plays guitar]. That tells my feeling. That’s the Blues.”

While a large library of books, recordings, and films celebrate the amazing career of B. B. King, it is his music that speaks most eloquently to us. In “Why I Sing the Blues,” he explains why the Blues are so powerful, so enduring:

Man was standing over me, and a lot more with a whip.

Now everybody want to know why I sing the Blues.

Well I’ve been around a long time, I’ve really paid my dues.