In history’s long parade of military heroes, few can rival Sergeant Alvin C. York

-

Fall 2018 - World War I Special Issue

Volume63Issue3

Early in October 1918, the Meuse-Argonne offensive smashed into Germany’s Hindenburg line. Allies outnumbered the enemy eight-to-one but the offensive stalled. Germans had laced the Argonne Forest with machine guns. A cold October drizzle turned roads into muck. Advances expected to make eight miles a day made only three, forcing U.S. General John “Blackjack” Pershing to call a halt. For three days, troops regrouped, and officers reconsidered. When the offensive resumed, a single soldier among the 820,000 would become the most celebrated hero in American military history.

Towards noon on October 8, soldiers in the 328th Infantry were alarmed to see a hundred or more Germans striding toward them. All but a few had their arms up. Three American riflemen marched on either side, and in the lead was a lone corporal carrying an Enfield rifle in one hand and a Colt .45 in the other. Once the prisoners were corralled, the story of their capture came out.

It seemed unbelievable, impossible. The jug eared, freckle-faced corporal leading the prisoners had captured them — all of them.

When word reached the brigade commander, he approached the soldier. “Well, York,” he said. “I hear you have captured the whole damned German army.”

Corporal York saluted. “No,” he said in his Tennessee drawl, “just 132.”

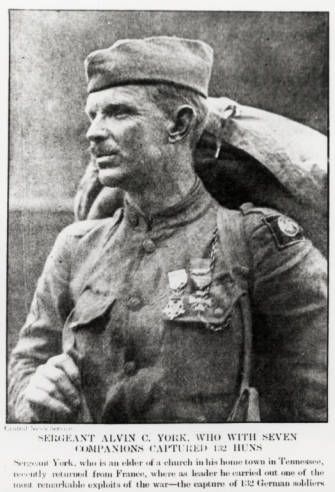

In history’s long parade of military heroes, few rival Sergeant Alvin C. York. For a half-century following World War I, the name Sergeant York was synonymous with courage and duty, God and country. He was decorated with every major American medal plus France’s Legion of Honor and Croix de Guerre. Sergeant York was the subject of biographies, legends, and a movie starring Gary Cooper. He met presidents. His name graced a highway, a movie theater, buildings, and streets. Novelist Robert Penn Warren based characters on York, and when F. Scott Fitzgerald detailed Jay Gatsby’s war exploits, he set them in the Argonne Forest where Gatsby earned medals from many countries, including, like Sergeant York, one from “little Montenegro down by the Adriatic Sea.”

Yet there was a hero within the hero. Like most veterans, Sergeant York was uncomfortable when thanked, again and again, for his service. Asked to recount his heroics, he often said, “I am trying to forget the war. I occupied one space in a fifty-mile front. I saw so little it hardly seems worthwhile discussing it.” He often claimed that his most important work was in the mountains where he grew up. And when all the parades were over, all the fanfare faded, Sergeant York’s efforts to improve the life of “my people” remain his lasting legacy.

Pall Mall, Tennessee was just a handful of cabins in a hollow when Alvin Cullum York was born there in 1887. The town, a local said, was “just as far up in the Cumberland mountains as you can get without starting back in the other direction.” Fentress County, just over the mountains from Kentucky coal country, provided a rugged living for 8,000 residents, hunters far outnumbering farmers. In a one-room schoolhouse, a single teacher taught 100 kids. With no high school for miles, few went beyond sixth grade.

Alvin York was the third of eleven children born to a blacksmith and his exhausted wife. At age six, York began hunting with his father. William York was “the best shot in the mountains,” Alvin remembered, but the old man “threatened to muss me up right smart if I failed to bring a squirrel down with the first shot or hit a turkey in the body instead of taking its head off.”

Leaving school after third grade, York grew up barefoot and bone poor. He might have stayed that way had William York not been kicked by a mule. Alvin, then 24, found his father’s death “an awakening.” As head of the family, he struggled to run his father’s blacksmith business. When fire destroyed the shop, he found odd jobs on farms and road crews. The hard work turned him to hard play. “Alvin was a wild boy,” his mother said. York later remembered “almost always spoiling for a fight.” Gambling and carousing, he took to drinking moonshine, often in contests to determine the last man standing.

But York also entered another type of contest — shooting. Even in a region of hunters, he stood above the rest, shooting with either hand, picking the heads off turkeys at forty yards. Others in Pall Mall called him “Big ‘Un” — he stood 6’2” — and kept their distance. When Alvin fell in love with 14-year-old Grace Williams, her parents were appalled. The couple had to “court on the sly for a while,” Grace remembered.

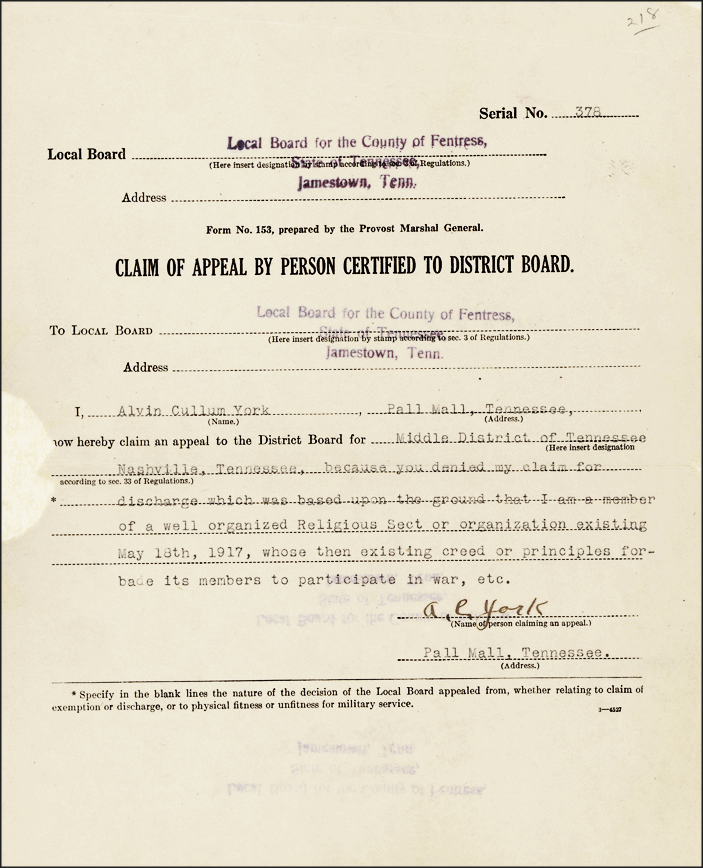

In the summer of 1914, when war erupted in Europe, news from the Western Front took its time reaching Pall Mall, Tennessee. By the time it did, Alvin York had prayed for salvation and found his sins forgiven. York joined the Church of Christ in Christian Union, a small sect that refused to support the Confederate cause and split from the Methodists during the Civil War. As a devout church goer, York took Biblical commandments as gospel. So when the United States entered the Great War, York was torn between God and country.

“I believed in my Bible,” he remembered. “And it distinctly said ‘THOU SHALT NOT KILL.’ And yet old Uncle Sam wanted me. And he said he wanted me most awful bad. And I jest didn’t know what to do. I worried and worried. I couldn’t think of anything else. My thoughts just wouldn’t stay hitched.”

York dutifully signed up for the draft but when the registration form asked, “Do you claim exemption from draft (specify grounds)?” he scribbled “Yes, do not want to fight.”

Some 20,000 Americans claimed conscientious objector status during the war. Those inducted as non-combatants were hounded by fellow soldiers, often until they agreed to shoulder arms. But Alvin York never got the chance to become a target. His church, unlike Quakers or Mennonites, had no pacifist standing with draft boards. Refused CO status, York was drafted in June 1917. For the first time in his life, he left the mountains to enter “the big outside world.”

During basic training in Georgia, York’s commanding officer recognized the “plowboy” as a sincere pacifist and sent York home to weigh faith against patriotism. He walked for hours in the mountains, knelt and prayed, walked some more. “I begun to understand that no matter what a man is forced to do, so long as he is right in his own soul, he remains a righteous man,” he remembered. “I knowed I would go to war.”

In May 1918, York was one of 230,000 American doughboys sent “over there.” After a summer of drill, York’s Eighty-Second division reached the Western Front.

During the battle of Saint-Mihiel, York patrolled the trenches with a bulky automatic weapon. He said he’d prefer a sawed-off shotgun, yet he held his ground and was promoted to corporal. Twelve days after liberating two towns on the Saint-Mihiel salient, York’s division joined the Meuse-Argonne offensive. As planned by General George C. Marshall, later to devise the Cold War’s Marshall Plan, the offensive would culminate more than a year of American mobilization and, it was hoped, break the stalemate and end the war. But Germany was ready.

Defending the Hindenburg line, German forces were layered ten miles deep. The last defense was the line itself, its walls named for witches in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. The defense, General Marshall said, was “the thickest and most elaborately rarified earthworks zone ever assaulted by U.S. troops.” Three days of fighting wreaked massive Allied casualties. In the confusion, an entire American battalion was isolated behind enemy lines.

On October 6, the 328th Infantry Regiment took on a new assignment — assault high ground behind the Argonne Forest and find the “Lost Battalion.” Fighting was fierce. The Lost Battalion had survived days of hunger, isolation, and an attack of flame throwers.

See "Tales of the Lost Battalion" by Edward Lengel in this issue.

When York’s regiment took Hill 223 near Chatel-Chéhéry. the desperate battalion was finally brought to safety. But the next day, rain, sniper fire, and artillery mired the regiment again. Then came the dawn of October 8, the day that would change Alvin York’s life.

An artillery barrage was supposed to cripple German defenses, but none came. At 6:10 a.m., York and his battalion raced down Hill 223 and across a valley toward German machine guns dug into the hills. When they reached flat ground, York recalled, they met “a regular sleet storm of bullets. I’m a-telling you that-there valley was a death trap.” York saw men stagger and drop “like the long grass before the mowing machine at home.”

Reduced to just seventeen men, York’s squad decided to flank the Germans. Skirting a wooded hill, they slipped past machine gun nests, moving behind enemy lines. Approaching from the rear, they surprised two German medics. The men bolted and ran.

Alerted, the enemy turned and “fired on us from every direction.” York managed to capture a few surprised soldiers and their commanding officer, but machine gunners on the heights signaled for the prisoners to drop to the ground. Then the guns opened up again. Sergeant Bernard Early and eight others fell, leaving just eight behind enemy lines. That was when Alvin C. York, mountain man, former pacifist, sharpshooter, became a legend.

Charging up a hill, York crossed a supply line and dropped to the ground. He was below the sight of machine guns on an elevated ridge. The angle forced German gunners to raise their heads to aim. Each time a head popped up, York fired. The Tennessee sharpshooter later reckoned he “teched off” 18 men with 19 shots. The enemy took cover but when York moved back towards his men, a dozen Germans with bayonets charged.

York began “shooting the way we shoot wild turkeys at home. You see, we don’t want the front ones to know that we’re getting the back ones. … I knowed, too, that if the front ones wavered, or if I stopped them, the rear ones would drop down and pump a volley into me.” So he targeted trailing soldiers while a private picked off others. Finally, the captured commander shouted at York.

“English?”

“No, not English.”

“What?”

“American.”

“Good Lord! If you don’t shoot any more, I’ll make them give up.”

York and his company marched the captives back to American lines, gathering more prisoners coming out of the hills. The story astonished everyone but did not spread beyond the company — yet. There was “a war to win.” Corporal York became Sergeant York and the Meuse-Argonne offensive continued. For weeks on end, 500 doughboys per day were killed, a thousand more wounded. It was the highest casualty rate in American military history, but the assault tipped the balance of the war. Germans surrendered in droves, the Kaiser’s government toppled, and on November 11, Sergeant York celebrated the armistice with the rest of the world.

For several months, York’s story went unreported, just as the army preferred. “Blackjack” Pershing believed the nation needed healing more than heroes. To single out one man was to lessen the sacrifice of others. “My feelings are the feelings of the Mothers and Fathers of this country when you pick out one man and proclaim him the greatest hero,” Pershing said. The nation, however, did not agree.

On April 26, 1919, the Saturday Evening Post published “The Second Elder Gives Battle.” Describing the exploits of one Alvin C. York of Tennessee, journalist George Pattullo was not shy about making an All-American hero. York, who had retraced his actions for Pattullo, had single-handedly taken 132 prisoners using “particularly American weapons.” He was, “unflustered. . . unhurried, half-indolent,” possessed with an “absolute sureness of self.” And best of all, the hero was not from Manhattan or Minneapolis but from good country stock of Appalachia.

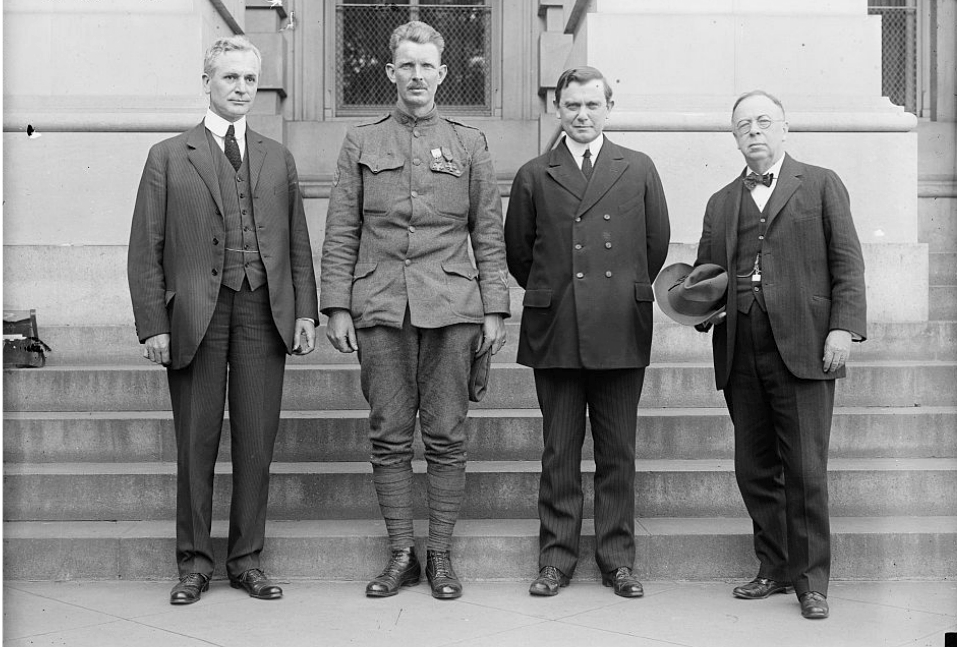

Still in France, York heard nothing of the Post article, but newspapers picked up the story. And in mid-May 1919, when Sergeant York disembarked in Hoboken, New Jersey, crowds met him at the dock. He was given a ticker-tape parade through Manhattan. The crowds, he said, “plumb scared me to death.” Learning that the entire nation was talking about him, York hunkered down. “I was sorter feeling like a red fox circling when the hounds are after it.” he wrote later. “They asked me that many questions that I kinder got tired inside of my head and wanted to get up and light out and do some hiking.”

York got a private tour of Manhattan. At the New York Stock Exchange, traders carried him on their shoulders. Then it was on to Washington, D.C. where he received a standing ovation in Congress, met the Secretary of War, and visited the White House. Finally, at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia, York was discharged. “I want to go home and see my mother first of all,” he told the press. Then he made “wide tracks” for the Cumberlands where he would try to forget the war.

But the American people would not let him forget. Death demanded a conqueror, a lone warrior on a pedestal. And here was a hero out of central casting. Like Daniel Boone, Sergeant York was a backwoods sharpshooter. Like George Washington, he won his war, then went back to the farm. Like Abraham Lincoln, he was humble and homespun. And like every fabled Western sheriff, he stood his ground alone.

“It is often said that the glory and the opportunity for individual exploit have all been taken out of war,” Secretary of War Newton Baker said in 1919, “but every now and then circumstances still make the opportunity, and certainly one such was made when Sergeant York, with his little band, found himself surrounded by machine gun nests in Chatel-Chéhéry on October 8, 1918.”

Back home, York married his childhood sweetheart, Grace Williams, and settled in Pall Mall. Asked about his exploits, he only said, “We know there are miracles, don’t we? Well this was one. I was taken care of — it’s the only way I can figure it.”

For several years, York was besieged by offers. Two thousand bucks to endorse a rifle. Ten grand for a book. Fifty thousand for film rights. York turned them all down. “My life is not for sale and I don’t allow Uncle Sam’s uniform for sale,” he said. “I just want to be left alone to go back to my beginnings.” The only offer he accepted was a 400-acre farm purchased by the Rotary Club.

Alvin and Grace had eight children, including Betsy Ross York, Woodrow Wilson York, Thomas Jefferson York, Sam Houston York, and Andrew Jackson York. Three biographies kept the story alive, but York focused his efforts on “improving conditions here in the mountains.” He lobbied the state legislature for better roads into Tennessee back country and in the mid-1920s, the Alvin C. York Highway opened. Then he set up the Alvin C. York Foundation with a simple goal — build a high school, the region’s first. “If I could make the school a reality,” he said, “I will be prouder of that than anything else I ever did.”

Speaking at fund-raisers, with his “aw shucks” Tennessee drawl, York earned enough money to build his school. But the York Agricultural Institute, opened a month after the stock market crash in 1929, soon struggled. York, who insisted on being chairman of the board, quarreled with seasoned educators. Seeking additional funding, he got tangled in the barbed wire of politics. He spent much of his farm income caring for his mother and growing brood. In 1933, Congress considered a bill to support him but the war was long past and his star was fading. He was finally ousted from his own school, a state board saying, “We seriously doubt his ability to head an educational institution with any degree of success.”

York might have been left on the shelf of American heroes had it not been for Hollywood. In 1939, with another war looming, producer Jesse Lasky saw in York a story “of vital importance to the country in these troubled times.” York still wasn’t interested, but Lasky kept upping his offer. Finally, hoping to use the money to start a Bible school, and convinced his story might help America face mounting threats from Germany and Japan, York signed the movie deal. He got $50,000 plus two percent of the gross. Months later he was hobnobbing with Gary Cooper.

The ruggedly handsome “Coop” had refused the role at first, saying Sergeant York “was too big for me, he covered too much territory.” But as war raged in Europe, Cooper changed his mind. Directed by Howard Hawks, “Sergeant York” premiered in New York in July 1941. From opening credits to the tune of “America the Beautiful,” the film waved flag after flag. York and Grace seem cut from a Thomas Hart Benton painting. American doughboys charge the enemy to the score of Yankee Doodle. And York again captures “the whole damn German army” — by himself. After the movie, when York walked into the theater, he got a fifteen-minute standing ovation. “Sergeant York,” nominated for ten Oscars, became a minor classic, still available on DVD. York got his Bible school and a permanent place in among American war heroes.

World War II turned the former pacifist into a gung-ho patriot. He tried to enlist but was too overweight, so he headed his county draft board, inducting his own sons.

Breveted a major, he lent his name to a ghost-written syndicated column, “Sergeant York Says.” And when atomic bombs ended the conflict, York wholeheartedly backed the Cold War. Throughout the 1950s, he found the press eager to print his hardline comments. “We are going to have to go to Moscow to win the war,” he said. “Let’s take an A-bomb and go up to the head of the spring and muddy the waters.” If no one else was willing to “push the button,” he said, “I will.”

York spent his final years battling arthritis, high blood pressure, and the IRS. Disputing his reported royalties from “Sergeant York,” the IRS assessed back taxes of $172,000. Citizens lobbied President Dwight Eisenhower to “go easy” on York, by then confined to a wheelchair. Finally in 1961, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, born in the Cumberlands, established a Help Sergeant York Committee. Within weeks, 10,000 Americans contributed, paying York’s debts.

When York died in August 1964, President Lyndon Johnson proclaimed: “Sergeant Alvin Cullum York has stood as a symbol of American courage and sacrifice for almost half a century.” The New York Times obit hailed York as “the latter-day descendant of the American frontier, a plain-talking, no-nonsense sharpshooter. . . For an America fighting its first war on foreign soil, he was the perfect hero.”

Or was he?

Ever since the 1920s, doubt had dogged York’s legend. Members of his own company protested his medals, saying Sergeant Bernard Early deserved as much credit as York. Germans also cast aspersions, the captured officer calling his story “typically American megalomania.” The officer admitted he had surrendered, having “no choice,” but he had not given up all his men. An investigation by the German Reichsarchiv called York a “braggart” and a “liar.” Yet U.S. Army reports, in 1919 and 1935, concluded that “credit was given where credit was due.” Still, doubts remained. When the movie “Sergeant York” was released, soldiers from York’s company called the movie more fiction than fact. Ultimately, it took a colonel to cement the reputation of the sergeant.

One Saturday afternoon in 1973, nine-year-old Doug Mastriano was headed out to play when his father called him aside. “Sergeant York” was on TV. Mastriano had seen many war movies but none like this. “My idea of a hero back then was rooted in the rough and tough John Wayne type,” he remembered. “But the movie left a lasting impression on me. I wanted to know about Alvin York and why he was neither interested in being a hero or even serving in the army.” The story stayed with Mastriano as he started his own military career, and continued to nag him through his service in Operation Desert Storm, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Yet the more he learned, the more he was troubled by “the lack of precision in the record.” Mastriano spent 15 years reading every scrap of information about York. In 2002, he began visiting the Argonne Forest. Joined by scholars, forensic specialists, and fellow veterans, Mastriano formed the Sergeant York Discovery Expedition.

Mastriano’s expedition consulted maps, memoirs, and battle reports from both German and American sources. Then the team began combing the Argonne for pinpoint locations. A French historian in Chatel-Chéhéry guided Colonel Mastriano near the spot where York’s decisive firefight took place. In 2006, Mastriano, often wearing a black cowboy hat, was joined by his son, Josiah. A thousand hours of archaeological digging unearthed spent cartridges from German machine gun nests. German dogtags, buttons, and scraps of uniforms. Next the team found 46 Remington .30-06 cartridges along the road where York said he had “teched off” 18 men. And scattered in a five-foot radius, Mastriano found 24 shells from a Colt automatic. Forensic analysis confirmed the findings. The Remington cartridges came from a single 1917 Enfield rifle, while the .45 shells came from two guns, 15 from one, nine from another. This backed the story by York and Private Percy Beardsley that they had fought off the final German bayonet charge together.

In Alvin York: A New Biography of the Hero of the Argonne, Mastriano writes: “Starting in the meadow, the artifacts recovered illustrate that the Germans surrendered without resistance. . . Taken together, the events of the 8 October 1918 battle seem to come to life. Everything was exactly where it should have been based on the numerous threads of information discernible from the German and American battle accounts.”

On October 8, 2008, the French government opened the Sergeant York Historic Trail in the Argonne Forest. On hand for the ceremony were York’s surviving children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Visitors can now walk the trail the reluctant hero took into battle and stand on the site where he stood his ground. But there are other markers along Alvin York’s winding trail to heroism.

In Pall Mall, the Sergeant Alvin C. York State Historic Park welcomes visitors to York’s home. A dozen miles down the road stands the York Institute. Now in its 90th year, the institute hosts 600 students studying a full range of high school subjects. The school has high expectations, says principal Jason Tompkins, himself an alumnus. “When you come to our school,” Tompkins said, “we expect you to be exceptional, because we’re Sergeant York’s own.”

A century ago, this reluctant soldier emerged from the fog of war to embody every element Americans crave in a hero. The parades are now long past and American ideals of heroism are more complex. Yet the story remains, now proven with spent cartridges and forensics.

“Alvin York became a popular hero because within himself he caught the contradictory nature of the American character,” wrote biographer David D. Lee. “Americans consider themselves peace loving but respect men of action; York was a conscientious objector who became a war hero. Americans are materialistic but consider themselves idealists; York rejected wealth because the terms for accepting it violated his conscience. The celebration of Alvin York was really meant, in a larger sense, as a celebration of American life.”