Hidden in the park’s southwest corner, the lightly visited Bechler district offers a two-hundred-square-mile wilderness of meadows, hot springs, fantastic rock formations, and an unparalleled abundance of waterfalls

-

April 1998

Volume49Issue2

When William Gregg, a manufacturer and national parks enthusiast from Hackensack, New Jersey, visited Yellowstone National Park in 1920, his initial impressions were much like those many visitors take away today. “The tourist automobiles are now so thick on the park road that the superintendent has to establish one-way-street traffic regulations,” he reported in an article for The Saturday Evening Post . “And the designated camping grounds are so inadequate that often the auto caravans find themselves huddled uncomfortably. They fail to get that sense of bigness and freedom for which they come.”

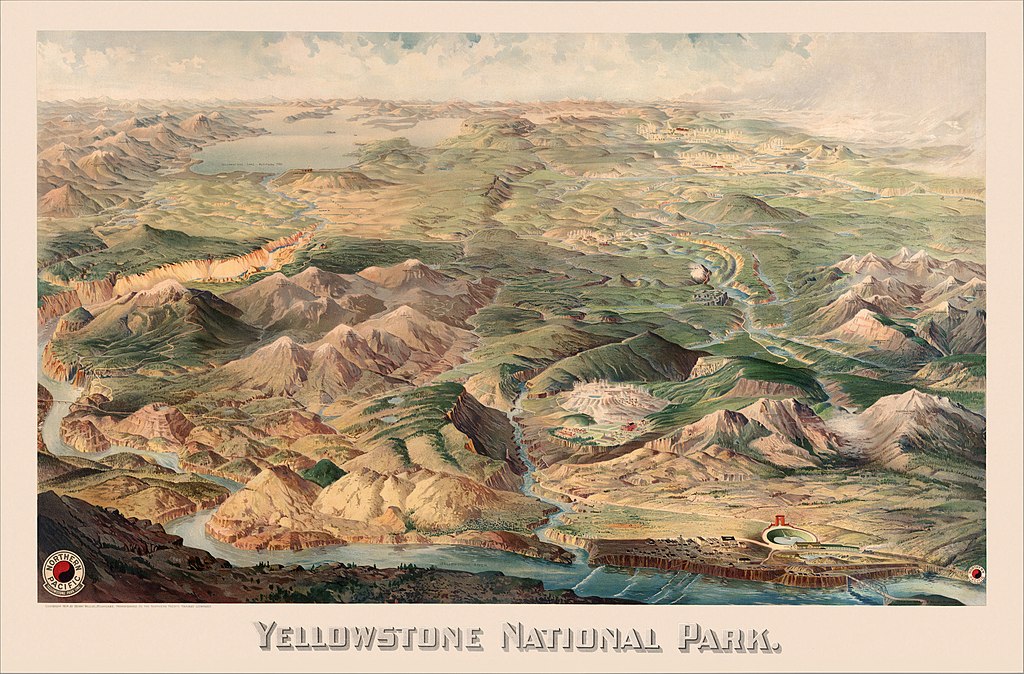

Unlike most of the huddled masses, Gregg had an escape route. His main reason for visiting Yellowstone was to investigate the park’s southwest corner, the little-known, seldom-seen Bechler district. Earlier that year Idaho’s congressional delegation had introduced legislation designed to help the drought-ravaged sugar beet farmers of its state, igniting the first skirmish in what would become a decade-long battle between conservationists and proponents of irrigation in the region. The legislators proposed placing a reservoir in the park’s Bechler area, reasoning that the land they sought to flood was pretty much useless; even surveyors’ maps had labeled it swamp. The legislation probably would have passed handily if Gregg hadn’t wanted to see for himself the eight thousand acres of meadow Congress seemed set to submerge.

So Gregg and his two daughters, intent on doing “some real exploration work” through the trackless country to the southwest, accompanied a packhorse outfitter from Old Faithful in August 1920. They crossed the Continental Divide and camped for three nights at the headwaters of the Bechler River, finding three waterfalls, several cascades, a hot spring, and fantastic rock formations—none mentioned on their government-issue topographical maps. From there they proceeded down the eight-mile Bechler River Canyon, past more unnamed waterfalls and cascades, before arriving in the broad basin that had been proposed for the reservoir. “We reached the mouth of the canyon in ample time to make camp for the night, finding solid meadow land, running water, and timber instead of the great swamp shown on the topographical map and so much talked about by the Idaho irrigationists,” Gregg later wrote. “What splendid meadows they are, and surrounded by what fine pine forests! Ten to twenty thousand acres of the best camping country in the world, and every stream is full of native trout!” Gregg added that the “Bechler River Valley is the widest, most level and most beautiful in Yellowstone National Park. Ten thousand individual automobile parties can camp in and around it with elbow room for all.”

Despite Gregg’s prediction, the Bechler Meadows never became a vast campground accommodating ten thousand cars. His writings did help keep the Irrigators at bay, but the Bechler area is as remote today as it was in Yellowstone’s earliest decades. A six-hour roundtrip drive from Old Faithful via eastern Idaho, or a thirty-plus-mile hike, this unknown Yellowstone is not for everyone; it has no geysers and no gift shops. But for visitors who have seen the park’s better-known sights, and especially for those who believe solitude is the best souvenir, the Bechler district is a destination worth pursuing.

I discovered the region on my fourth trip to Yellowstone. My first visit to the park had been A during the inferno of 1988, but instead of ruining a long-anticipated vacation, the fires made the visit especially memorable. I remember walking around Norris Geyser Basin, unearthly at any time. A tiny red midday sun piercing through the yellow-gray sky could have been any star, and the percolating cauldrons of thermal muck could have easily been the surface of some distant planet. Despite the fact that I was in the heart of the park, there was hardly anyone else around.

That wasn’t the case on my two subsequent visits, when I came to know the Yellowstone that visitors usually see, the place Gregg describes, with its traffic-choked main roads and packed campgrounds. Then I heard about the Bechler country, which, although long a favorite of hikers, was inaccessible by road from the rest of the park. When the park historian Lee Whittlesey told me about the 1920s proposal to flood the area, I knew, like Gregg, that I had to see it for myself.

Of the 3,000,000 people who visit the park each year (compared with the mere 79,777 who crowded in with Gregg in 1920), about 5,000 find their way to Bechler on a day trip and another 3,000 or so spend a night or more there. Most of them arrive in August and September because earlier than that the Bechler Meadows are indeed a swamp, made soggy from snowmelt and rainfall. As the waters recede around the Fourth of July, wildflowers carpet Bechler’s meadows and woodlands, but so do thick clouds of mosquitoes. Finally, by early to mid-August, chilly nights and gloriously warm days prevail, and Bechler is at its prime. Even then, however, subtle pleasures set the region apart: Take it from Ken Stepanik, an outfitter who leads trips into the region with his Montana-based company, Llamas of West Yellowstone. “Small things happen in the Bechler, but it’s the smaller things combined that make it a special trip, like being out under the stars and watching a moose in the moonlight, or sitting at Three River Junction with a cup of coffee, or coming on a mile and a half of huckleberries along the trail.” Gary Ferguson, who hiked five hundred miles through the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to research his 1993 book Walking Down the Wild , says he had one of the greatest wildlife experiences of his life in the Bechler Meadows, where a steady stream of creatures—first moose, then trout, then swallows and cranes and tanagers, then beavers, and finally muskrats—visited his riverside camp for what he later described in his book as “the Mardi Gras of animal parades.” “There are places in the backcountry where you just feel like you’ve stumbled into Eden,” Ferguson told me, “But I don’t know that I’ve ever felt that as strongly as I did in the Bechler.”

The Bechler District is actually Yellowstone’s second-busiest backcountry area (after Shoshone Lake), yet in a day you’re unlikely to meet more than two dozen people on its trails. That’s because like all of Yellowstone, it’s big country, encompassing about two hundred square miles—which is probably why the Idaho legislators figured no one would miss the twelve-square-mile parcel set aside for a reservoir. “There is absolutely nothing in the way of unusual scenery or other interesting features in this part of the park, but the entire area contains only the ordinary Western mountain landscape scenes, such as may be seen along the lines of travel for many miles by any tourist approaching the park from any direction,” Rep. Addison T. Smith of Idaho told Congress in pushing for the reservoir. To this assessment Gregg responded, “I am compelled to say this does not square with what I found and saw there.”

Gregg and other early enthusiasts saw the waterfalls that give this area—named for Gustavus Bechler, a topographer with the 1872 U.S. Geological Survey party—its much more poetic nickname, the Cascade Corner. Two factors combine to make waterfalls especially abundant in this part of Yellowstone. First, the Bechler area receives the park’s highest precipitation, about eighty inches annually. Second, the broad meadows are surrounded by dramatic plateaus and ridges that provide plenty of steep drops for cascading rivers and streams. While preparing a book on Yellowstone’s waterfalls, the modern-day Yellowstone explorers Lee Whittlesey, Mike Stevens, and Paul Rubinstein catalogued fifty-four falls and cascades. There are the 250-foot Union Falls and 260-foot Albright Falls, tied for second place in height behind only the park’s far better-known 308-foot Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River. (Silver Cord Cascade, a slender ribbon-like fall plunging more than 800 feet into the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, generally is put in a category by itself.) There are also Dunanda Falls, a veil-like 150-foot drop on Boundary Creek; the thundering Cave Falls, Yellowstone’s widest at nearly 300 feet across; and Ouzel Falls, 230 feet, visible from miles away across the Bechler Meadows. “In any other place on earth, whole parks would be built around any one of these,” says Whittlesey. “Here, many don’t even have names.”

On my own visit to the Bechler, I had time for only one long day hike, so I had to choose between seeing just Union Falls, by most accounts the most spectacular, but set off by itself, or going for quantity in the Bechler Canyon. I finally settled on Union Falls. Since this is grizzly country, I persuaded a Bechler subdistrict ranger, Ann Marie Chytra, to let me accompany one of her seasonal rangers, Micah Wood, on his patrol hike back to Union Falls, and I was happily astounded when Wood told me that during his summer he had not seen one bear prowling the backcountry.

Union Falls is a twenty-two-mile roundtrip hike from the Bechler Ranger Station. Wood and I agreed that was too long for a single day, so we drove out of the park and west, then south, then east to the Ashton-Flagg Ranch Road. We took a badly rutted Forest Service road to the alternate trailhead near Fish Lake; from there Union Falls was about eight miles away. It was all easy going except for three river crossings, swift and cold and up to my thighs even in late August. Along the way Wood and I traded stories of Bechler past and present.

The Bechler District, like all of Yellowstone, has a sketchy human history. There is no record of Native American settlement in the park’s southwest corner, although several tribes used the region as hunting grounds. John Colter, a veteran of the Lewis and Clark party, was the first white man to see the interior of Yellowstone, in 1807, but there’s no indication that he reached the Bechler region. Osborne Russell, who spent a decade from 1834 to 1843 trapping in the Rocky Mountains, made the first recorded visit to the Cascade Corner. On August 10, 1838, Russell and his party were traveling just southwest of the present Yellowstone boundary when, his journal recalls, “we fell on to the middle branch of the Henrys fork which is called by hunters the Falling fork for the numerous cascades it forms whilst meandering through the forest previous to its junction with the main river … we ascended this stream passing several beautiful cascades for about 12 miles when the trail led us into a prairie seven or eight miles in circumference in which we found the camp just as the sun was setting.” Even though they were but a few miles from even more impressive falls than the ones they had seen along the Fall River, the main Bechler waterfalls hidden in the park’s interior went undiscovered for another half-century.

In fact the Bechler area remained unexplored for many years after Russell’s brief visit. The first major park survey, undertaken in 1869, apparently skipped over the southwest corner, but it paved the way for the ambitious 1872 survey, led by F. V. Hayden, which did find and name the Bechler River. Hayden’s party persuaded Congress to name Yellowstone the first national park in 1872, setting it aside as a “pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” and guaranteeing its “preservation, from injury or spoliation, of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within.”

In 1885 surveyors led by the geologist Arnold Hague traveled widely in the Bechler region, discovering and naming Iris, Colonnade, Ouzel, and Union Falls. The last was the most remarkable find, considering its location high up Mountain Ash Creek, far from the region’s other landmarks. As we neared Union Falls, I wondered aloud to Micah Wood how Hague and his men ever came across it. “Just out of curiosity,” he said. “They probably just followed the creeks to see where they’d lead.” Wood added that he’d done it himself one day, shunning the easy Union Falls Trail to trudge along Mountain Ash Creek, following every meander and riffle to the base of the falls. But he wouldn’t be seeing Union Falls today. To his distress Wood spied a pot of stew simmering unattended in a backcountry campsite a mile from the falls, forcing him to wait for the campers’ return. If they didn’t have a damn good excuse for leaving food in bear country, he would issue them a ticket. “You might as well go on up,” he told me.

Until now the trail had been flat, but the final approach to Union Falls was a sturdy climb. When I arrived at the falls overlook, I was blessedly alone. There was a small ledge that reminded me of a balcony box at the opera; it was the perfect perch from which to watch a ceaseless performance. Union Falls got its name because it is actually the marriage of two creeks joining at the plunge, the torrents cascading into tendrils as the water spills over a broad cliff. The effect is mesmerizing, like tongues of flame in a campfire, and I sat staring at the spectacle a long time before the buzz of a fly snapped my reverie.

The Bechler country was just being settled by the time the Hague party did its work, and it soon became apparent that poaching was a problem. By the 1890s the U.S. Army, which managed Yellowstone until the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, was sending scouts to control unauthorized hunting. In an article in Harper’s Weekly in 1898, Elmer Lindsley, an Army scout, described the poachers: “Off the south part of the west boundary lives a gang of hardy mountain pirates who make a scanty living by hunting, trapping, and fishing. To these men the buffalo and moose of the Park are an irresistible attraction … such skilled robbers are they and so minute their knowledge of the country that [it] is almost impossible to catch them redhanded, and so zealous are they in one another’s defense that it is quite impossible to convict them unless so caught.” In 1900 the acting park superintendent, George Goode, proposed that a permanent military station be built at Bechler. It was finally erected in 1911, and it still stands, used to house Bechler-area staff.

As a threat to the Bechler country’s future, poaching paled alongside the land grabs of the 1920s. To fight a lingering drought in their state, the Idaho politicians John Nugent and Addison Smith began an effort in 1919 to obtain reservoir sites in the falls and Bechler river basins within the park, and early in 1920 they introduced bills to authorize the cost of construction of ditches, roads, buildings, and telephone lines. The U.S. Reclamation Service, noting that maps from the Hague survey had labeled the region “swampy,” backed the project, and even Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane favored the idea.

Yellowstone’s superintendent, Horace Albright, and the National Park Service director, Stephen Mather, pleaded with Lane to change his mind and encouraged conservationists to join the battle, but Lane stood firm and ordered the Park Service to prepare a favorable report on Smith’s bill. So Mather and Albright found ways to stall. One story has it that after a junior Interior Department bureaucrat alerted Albright to Lane’s decision to send a survey party to the Bechler country, Albright sent the horses the group would need out to pasture and the boats they’d requisitioned into winter storage. Mather meanwhile cited urgent personal business as a subterfuge for delaying his report. None of this worked, though, and when hearings began on Smith’s bill, Lane remained steadfast in his support of the measure.

Albright and Mather prepared to resign over the matter, but they never had to. Lane, citing ill health, left the cabinet, and his successor, John Barton Payne, helped the Park Service block the bill in the House. Meanwhile, Gregg’s Saturday Evening Post article fueled a public outcry, as did letters to many other publications. Writing yet another article about his Bechler explorations for The Outlook , a newsweekly, in 1921, William Gregg crowed, “Happily, the protest was so general and so emphatic that the bill died in the last Congress and has small chance of being resurrected again.”

For a time it seemed he was right. But 1926 saw legislation introduced to refine Yellowstone’s boundaries. Addison Smith, by then serving his seventh term in Congress seized on the bill as the perfect vehicle for removing the Bechler district from the park so a dam could finally be built. Once again, public dismay was swift and vocal. “To the Looters of Yellowstone Park: Hands Off! ” thundered The Outlook in the first of many editorials against Smith’s amendment.

I was thinking about the Bechler land grab when, the day after my Union Falls trek, I hiked toward the meadows the reservoir would have covered. After two miles of wooded trail, I reached tall grass, and I could almost imagine I was on the Nebraska prairie—until I looked and saw the Tetons rising far in the distance. Turning to the north, I spotted Ouzel Falls, named for the small birds that make nests in watery areas rife with insects and larvae. The falls drop 230 feet, but from here, several miles across the meadow, they looked tiny.

“Here is a meadow fit for giants to play in!” wrote Dr. Henry Van Dyke in a 1927 article for The Outlook . “I know not how many acres there are in the Bechler Meadows. But if it were only one acre, it would be too much to take away from the people of the United States, who own it as part of their pleasuring ground, and give to a few persons in Idaho or any other state.” Despite these protests, Washington again appeared ready to ignore the conservationists. In March 1927 a special Senate subcommittee appointed to investigate the boundaries bill reported in favor of Congressman Smith’s recommendation. But the Yellowstone Park Boundaries Commission’s report of 1930 retained Bechler Meadows within its borders. With that finding the second raid on Yellowstone’s Cascade Corner ended.

After the irrigation proposals were defeated, the Bechler region settled back into the anonymity it enjoys to this day. Poaching remained a problem for decades, and Bechler-area rangers still spend much of the off-season patrolling for illegal hunters. But the other controversies swirling in and around the park—from the devastating fires of 1988 to the re-introduction of wolves and the slaughter of bison wandering beyond the park’s boundaries—seem a world away. The Bechler area has made only minor headlines in the 1990s, once in September 1993, when crews finally went in to retrieve the wreckage of an Air Force bomber that had crashed near Trischman Knob thirty years earlier, and again in the spring of 1995, when Yellowstone officials announced the park would start charging its regular entrance fees to the Bechler district, despite the fact that the road dead-ends just two miles into the park.

During the 1920s, perhaps to make the Bechler country less remote for tourists, Horace Albright proposed a thirty-mile road from Lone Star Geyser near Old Faithful down the Bechler River Canyon. A preliminary survey was done, but no road was built. So the Bechler entrance remains Yellowstone’s most quiet by far, with no teeming visitor center, no cafeteria, nothing but a mimeographed brochure offering suggestions for hikes and tips for avoiding bears. The Bechler country is no longer undiscovered, exactly, but getting there takes a certain determination and a willingness not only to walk or ride horseback for many miles and ford thigh-deep rivers but also to let nature take the reins. And that, Bechler aficionados will tell you, is just the way wilderness ought to be.