The British are often cast as the tyrannical power in the Revolutionary War. But American patriots could also be ruthless in demanding fealty to their cause, as many Quaker families learned while attempting to remain neutral.

-

Fall 2020 George Washington Prize

Volume65Issue8

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist World of Trouble: A Philadelphia Quaker Family’s Journey through the American Revolution, by Richard Godbeer (Yale University Press).

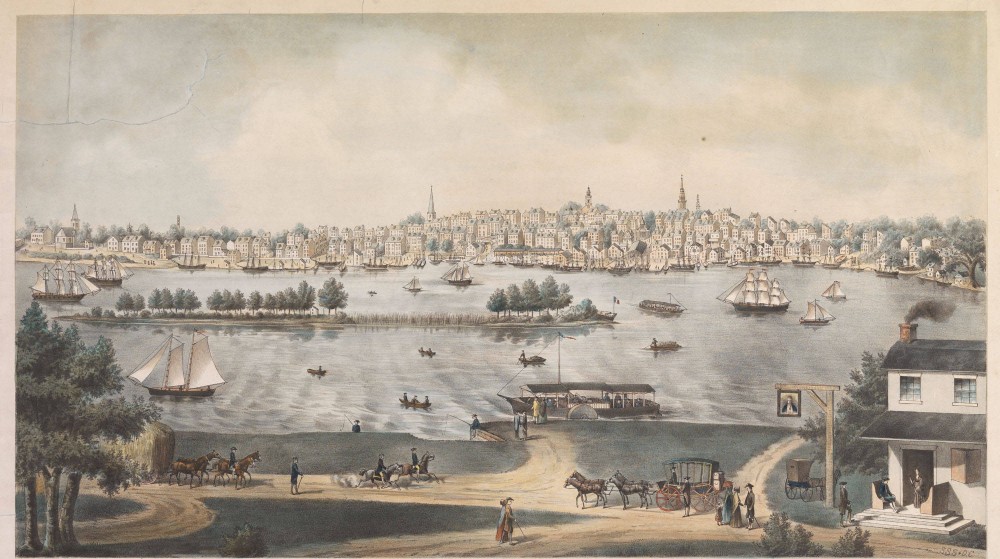

It was September 11, 1777, and the moment that forty-two-year-old Elizabeth Drinker had been dreading was finally arrived.

Elizabeth's husband, Henry, her senior by one year and a prosperous Quaker merchant, was among thirty men who had been arrested a week before on suspicion of treason. Pennsylvania's patriot government had brought no formal or specific charges against these individuals, but most were Quaker pacifists who refused to fight with or otherwise support either side in the War for Independence. The prisoners, locked up in a makeshift prison at the Masonic Lodge in Philadelphia, had written several letters of protest, denouncing their treatment and demanding a formal hearing. The Supreme Executive Council had informed them in turn that they must swear "allegiance to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, as a free and independent state," or suffer the consequences.

Only a third of the prisoners took the oath and secured their freedom; twenty remained in prison, nineteen of them Quakers. Their families and friends, outraged by what Elizabeth called "the tyrannical conduct of the present wicked rulers," visited them daily, waiting anxiously to see what would happen next. The revolutionary government had decided to send the prisoners to Virginia as exiles, with their ultimate fate uncertain. Most of the detainees were men of property, and the council had promised that they would be allowed to depart in their own carriages, as befitted gentlemen, but that promise was now broken, and they were to leave instead in wagons commandeered for the occasion.

The moment of departure turned out to be emotionally fraught and violent. Sarah Fisher, wife of prisoner Thomas Fisher, recorded in her diary that the prisoners were "dragged" outside into the wagons "by force" and then "drove off surrounded by guards and a mob." Yet not all of those who gathered to watch were hostile to the twenty men. When the time came for the prisoners' removal, wrote Thomas Gilpin, another of the exiles, the surrounding streets "were crowded by men, women, and children, who by their countenances sufficiently though silently expressed the grief they felt on the occasion.'"

As wagons carried the exiles away, torn from their loved ones, gunfire resounded in the distance. Elizabeth noted in her diary that the town was "in great confusion" that day. Patriot soldiers were fighting a few miles distant at the Battle of Brandywine to halt the British advance toward Philadelphia, and now her husband had disappeared into a war-ravaged landscape from which he might never reemerge. Elizabeth could not find the words to describe the prisoners' departure, but she wrote that night that afterward she had gone "in great distress" to a friend's house before returning to her own home and her five small children.

Over the coming days, she would assure Henry in a series of loving, anxious letters that he was "much talked of, and much felt for." In the meantime, Elizabeth faced an uncertain future as she assumed responsibility for protecting their home and young family against the horrors of war in a city held first by the patriots, then by the British, and then again by the patriots. By the time that Henry and the other prisoners returned eight months later amid growing controversy over their treatment, at no point formally charged with any crime, two of the exiles had died and Henry himself had endured serious illness. The "cruel separation" had proven a harrowing ordeal for him, Elizabeth, and their entire family.

The fate of the Quaker community remained in peril throughout the War for Independence. Most Quakers, including Henry Drinker, condemned the British policies that led to protest, rebellion, and ultimately revolution. Yet Friends, as Quakers called themselves, were reluctant to reject outright the crown's authority, in part because the monarchy had defended them for many decades against persecution, but also and crucially because of their commitment to pacifism and to reform over revolution. Eighteenth-century Quakers believed that subjects had the right and duty to resist unjust policies through peaceful protest but should not seek to overthrow any government that God had placed over them. Quakers envisaged that constitutional change would take place gradually over time as people developed a clearer sense of what was right and sought to create just governments through debate, negotiation, and, when necessary, protest. Their insistence that change should occur through an ongoing process of peaceable reform, not violence or revolution, made them anathema to patriots who now wanted a complete break from Britain and what they saw as its hopelessly corrupt, oppressive system of government.

The outbreak of war made Quaker pacifism even more aggravating for patriots facing the might of the British army: when most Friends adopted a position of principled neutrality, patriots doubted their sincerity and accused them of having secret loyalist sympathies, thus the wave of arrests.

Quakers had struck many people as dangerous ever since they first emerged as a radical dissenting movement during the English Revolution in the seventeenth century. Quakers rejected many beliefs central to mainstream Protestantism. Instead of seeing scripture as the sole and final source of divine truth, they believed each man and woman to have within them a spark of divinity that enabled them to discern and speak God's truth. That truth would emerge over time through revelation, which men and women of any social status might experience and then share. Their claim that apparently immutable truths were actually anything but stable appalled many contemporaries, as did the egalitarianism embedded within their theology. Quakers refused to bow, kneel, or remove their hats in the presence of social superiors, which outraged many contemporaries.

Early Quakers were vilified, jailed, and martyred, but the Toleration Act of 1689 granted freedom of worship to all Protestants and obliged British subjects on both sides of the Atlantic to become more tolerant of religious minorities. Pennsylvania's founder, William Penn, was himself a Quaker and insisted on freedom of conscience for all Christians who settled in his colony.

Whereas early Friends often adopted dramatic and confrontational tactics, in some instances even appearing naked in public as a form of prophetic expression, later Friends were much less disruptive and presented a calm, soberly dressed appearance to the world. Even so, the Society of Friends remained controversial and during the revolutionary era became once again vulnerable, even in Pennsylvania, targeted by patriots as a dangerous dissident voice. The arrests of September 1777 targeted Quakers in particular, but they aimed to intimidate into compliance anyone who questioned patriot principles or tactics as the Revolution pitted Americans against each other as well as against the British government. "All wars are dreadful," wrote Elizabeth, "but those called civil wars more particularly so."

The American Revolution was, to be sure, nowhere near as bloody as the revolutions that erupted in France and Saint-Domingue a few years later. The uprising by slaves against French rule in Saint-Domingue that began in 1791 led to wholesale slaughter on both sides, and the revolutionary government in France sentenced more than sixteen thousand alleged counter-revolutionaries to death by guillotine during the infamous Reign of Terror in 1793-94. America had no guillotine, and the number of those hanged as traitors to the Revolution was modest when compared with the state-sponsored carnage in France.

Yet many lost their lives in America's first civil war. Nearly five times as many Americans died in the War for Independence, relative to the size of population, as in World War II. Roughly one in five Americans remained loyal to the crown, and one in forty went into permanent exile as loyalists, the equivalent of almost eight million people today, their property confiscated by the patriots. Many who remained had their doubts about the Revolution. Those who spoke out often paid dearly for doing so: in Pennsylvania alone, the revolutionary government accused at least 638 individuals of high treason.

Yet the new regime minimized overt dissent through a campaign of intimidation and violence. However noble its official founding ideals, the United States was born in blood, its midwife a campaign of terror. During the decade before Independence, patriots had proven ruthless and brutal in suppressing dissent. So-called committees of safety published the names of those who refused to support boycotts of British goods, denouncing them as enemies of American liberty and declaring, "Join or die!" That phrase was menacingly ambiguous: at whose hands would people perish if they failed to join the resistance movement, a tyrannical Parliament in London or local patriots determined to squash any views but their own?

Printers who dared to criticize the patriots had their presses smashed and their publications burnt. Militant gangs known as the Sons of Liberty assaulted noncooperators, humiliated them, and tortured them. One of their favorite techniques was tarring and feathering. They stripped their victims in public and poured hot tar over their naked bodies, scalding and burning their flesh; they sometimes actually set them on fire. Next, they covered them in feathers and paraded them through the streets, beat them, whipped them, and often tied them to the local gallows.

These ritualized assaults were not random or exceptional but key components in a strategy of intimidation. The circulation of accounts describing these attacks, in graphic detail, ensured that the victims served as examples of what lay in store for others who disagreed with the patriots, for whatever reason, and would have terrified all but the staunchest of souls." Many years later, as the war neared its end, the patriots were still wielding terror against those who questioned their principles or tactics.

News of the British surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, which effectively guaranteed Independence, reached Philadelphia three days later, and patriots immediately set about planning a victory celebration. They announced that in the evening of October 24 every household should put candles in its windows and so create a citywide latticework of flickering light as crowds made merry in the streets. Yet not all Philadelphians were eager to take part in this celebration, and many Quakers, including the Drinkers, refused to illuminate their homes. They soon found out that patriots were in no mood to tolerate noncompliance. That night a crowd made its way through the streets, threatening those who refused to cooperate and vandalizing their homes. However great the temptation may have been to appease the mob by lighting candles, some households had the courage to stick to principled refusal, regardless of the consequences. When John Drinker, Henry Drinker's brother, declined to illuminate his house, patriots gave him a beating and stole much of the inventory from his shop. Henry and Elizabeth Drinker escaped personal injury, but their home did not: the mob broke about seventy panes of glass in their windows, cracked the front door as they broke it open, and then threw stones into the house, smashing two panels in the front parlor.

It was a terrifying night, Elizabeth wrote, and "scarcely one Friend's house escaped ... many women and children were frightened into fits, and 'tis a mercy no lives were lost." Elizabeth and Henry Drinker chose neutrality over patriotism or loyalism and paid dearly for that choice at the hands of those who had no patience for anything but unconditional support. That Elizabeth and Henry survived to tell their story was not a foregone conclusion, and their journey left deep scars that make them poignant characters with whom to travel through those turbulent revolutionary decades.

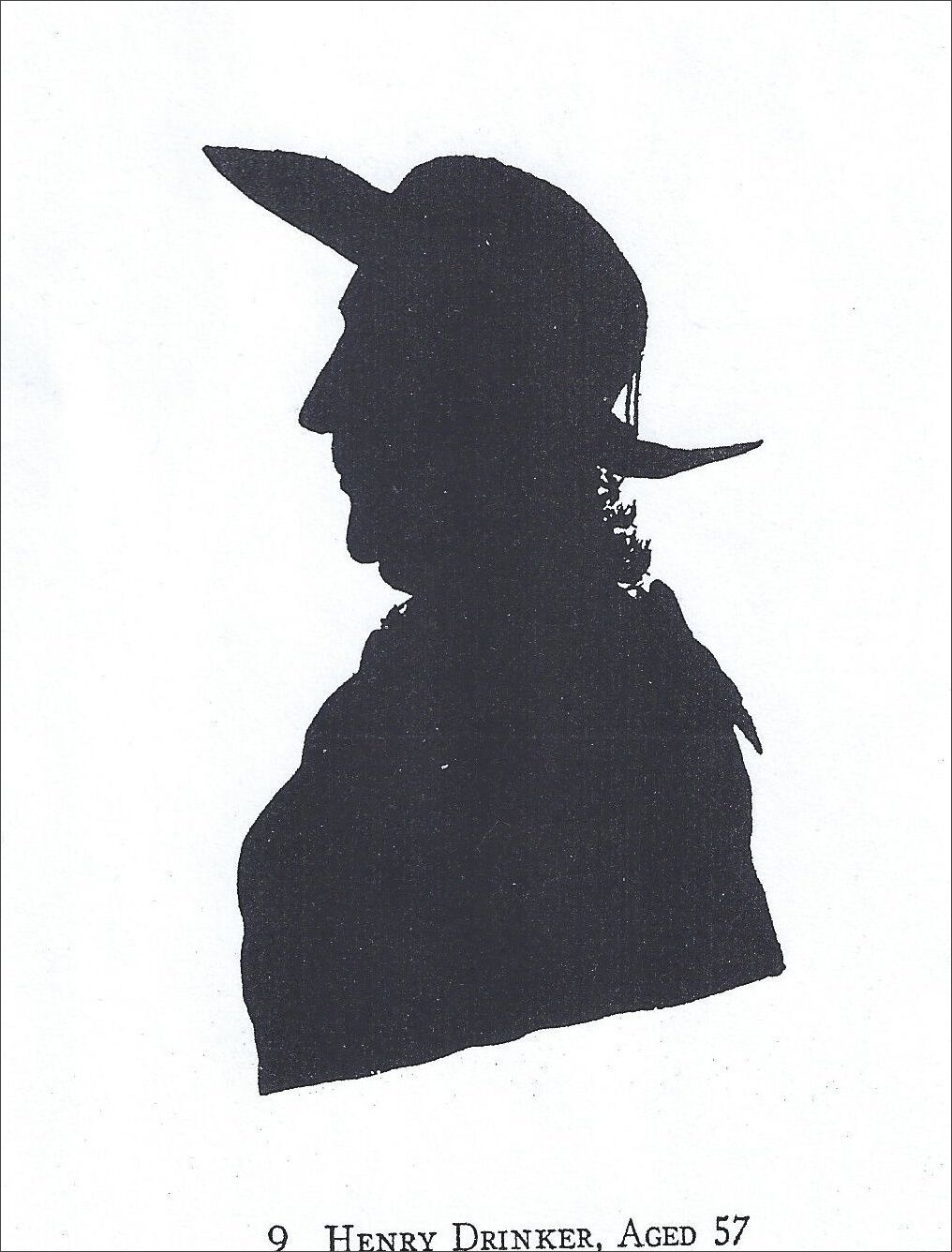

Henry Drinker (1734-1809) and Elizabeth Sandwith (1735-1807) married in 1761, just before the first wave of protests against imperial policy. Henry was an upwardly mobile merchant and would soon become an influential member of the Philadelphia business community as well as a leading Friend in the city. When Elizabeth and Henry settled in Philadelphia's commercial district as a respectable young Quaker couple, they had no way of owing that within a few years their world would come crashing down around them due to the rupture between Britain and its North American colonies. Economic boycotts followed by open rebellion had potentially ruinous consequences for merchants like Henry Drinker and placed them in a delicate situation as they tried to navigate between growing pressure to cooperate with economic boycotts, their own commercial interests, and their personal perspectives on the crisis.

Henry and his trading partner, Abel James, made their own situation much more perilous in 1773 when they agreed to become local agents for East India Company, which had secured from the British government a monopoly on tea imports to North America and soon became a reviled target for colonists who opposed imperial taxes on imported goods. That unfortunate decision, in combination with Henry's reputation as a leading Quaker, led to his arrest in 1777, on suspicion of treason against the new regime. During Henry's exile, the British forces occupied Philadelphia, and Elizabeth found that she had no choice but to take in one of the British officers and his retinue as billeted houseguests. The war quite literally invaded her home as the larger drama of revolution merged with the intimate drama playing out in the Drinker home. Even after Henry's return, neither he nor his family could take his survival for granted as patriots regained control of the city and resumed their persecution of anyone who refused them unconditional support.

Many Quakers, including Henry and Elizabeth Drinker, felt that the protest movement, though launched in support of liberty, had rapidly become another tyrannical regime with blood on its hands. As one of the exiles put it, "A people who had professedly risen up in opposition to what they called an arbitrary exercise of power, were in a little time so lost to every idea of liberty as to see, without dreading the consequences, the very foundation of freedom tom up." Elizabeth referred sarcastically to the "Guardians of Liberty," condemning them as "unfeeling men" and "cruel persecutors."

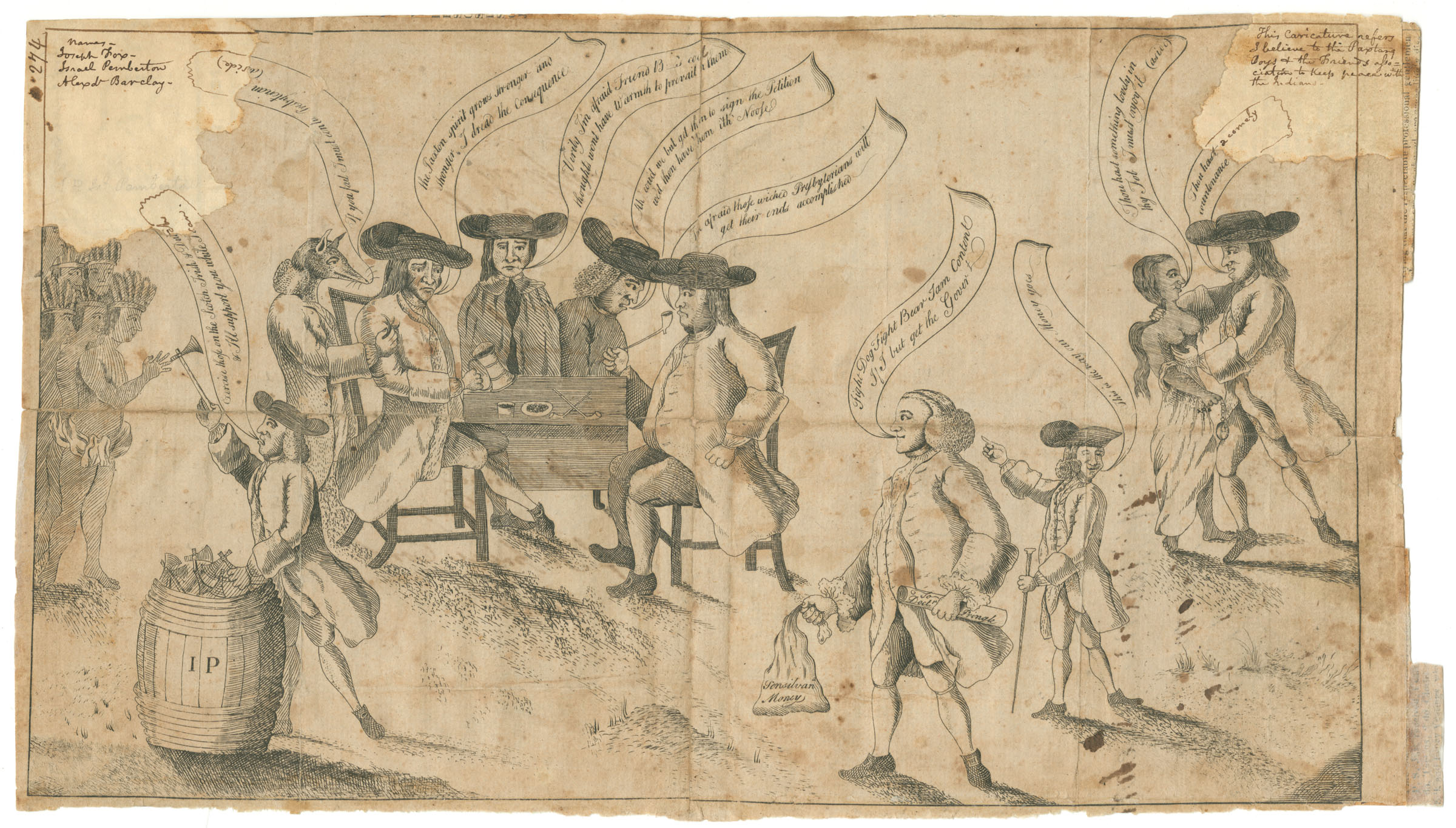

Yet some contemporaries were equally harsh when commenting on Quakers and their claims to the moral high ground. Pennsylvania Friends were, in truth, partly to blame for a resurgence of hostility toward them. Over the preceding decades, they had played a prominent role in creating an increasingly toxic political environment. Eighteenth-century Friends turned out to be resourceful and ruthless in working to maintain a decisive influence over public affairs in Pennsylvania even as they became a minority within the colony, much to the irritation of non-Quakers who felt their views should have more sway. Their enemies also accused them of reinterpreting their religious principles from one occasion to the next as it served their own interests, so that an ethos of evolving truth became, or so it seemed to their adversaries, a convenient tool of cynical powerbrokers. Quaker commitment to pacifism seemed, moreover, both dangerous and callous as Native Americans threatened the lives of frontier settlers, so that their enemies depicted them as Indian lovers and traitors to fellow Pennsylvanians.

Meanwhile, just as Elizabeth and Henry Drinker reached adulthood, the Society of Friends embarked on a program of internal reforms known as the Quaker Reformation. That movement aimed to close what reformers saw as a widening gap between values that Friends claimed to hold dear and their actual behavior. Reformers called for the stricter enforcement of codes regulating personal conduct and sought to instill a renewed sense of corporate identity. As colonial society became increasingly diverse and cosmopolitan, Friends should turn inward and become as far as possible a closed community, placing their trust in one another and avoiding the influences of a corrupt outside world. Yet when a group of prominent Friends resigned from political office in 1756, declaring that they now believed they could not reconcile their values with active involvement in public life, their neighbors noted that other Quakers continued in office, while yet others worked behind the scenes to shape public policy. Wealthy Quaker merchants in particular ensured that the assembly still protected their interests, sometimes at the direct expense of poorer Pennsylvanians. As the Society of Friends became increasingly introverted and tribal, so it became ever more vulnerable to accusations of separatism, self-interest, and hypocrisy.

The climate of resentment and suspicion that Friends had helped to create over the preceding decades now came back to haunt them. When Quakers began to distance themselves from violent protests against British legislation and when they refused to fight in the Continental Army, not everyone was willing to assume that their motives were honorable. After all, merchants such as Henry Drinker stood to surrender significant profits because of the nonimportation agreements, to say nothing of open warfare, and poorer workers whose interests the merchant class had done little to protect over the years now figured prominently among the more radical protesters. Based on prior experience, some Philadelphians might well suspect, however unfairly, that the positions taken by affluent Friends were nothing but a flimsy camouflage for self-interest.

As the colonies declared themselves states and fought in defense of their freedom, roughly one-fifth of Quakers broke with their brethren to side with the patriots, while a smaller number became loyalists, but the overwhelming majority of Friends adopted a position of neutrality. Their overriding loyalty lay neither with Britain nor with the new nation that patriots had determined to found but instead with their own Society of Friends, which they characterized as a holy nation in its own right, held together by moral principles to which they must remain loyal. Given the political and economic influence of Quakers in Philadelphia, their neutrality presented supporters of Independence with a significant problem. Instead of treating Quakers and loyalists as two distinct groups posing two distinct challenges, patriot pamhleteers such as Thomas Paine now exploited a cumulative reservoir of skepticism about Quaker sincerity and deliberately conflated them with the Loyalists: anyone refusing to support their cause wholeheartedly was an enemy of the Revolution and should be treated as such.

Living through the violence and intolerance of dissenting voices that marked the revolutionary era was a frightening ordeal for Americans in general and Quakers in particular, yet the Drinkers lived through not one but several interconnected revolutions that make this period and their story even more gripping. Social, economic, and cultural transformation combined with political drama to create an era of unnerving upheaval and uncertainty. Changing attitudes toward sex, courtship, and marriage, across American society and specifically within the Quaker community, had profound implications for young people and older adults who wanted to protect or control them. Henry and Elizabeth were part of a pioneering generation that placed a much greater stress on romantic courtship than earlier couples had done. This romantic revolution had profound consequences, not least in creating expectations that sometimes went unfulfilled once couples settled into married life. As parents, Elizabeth and Henry worked hard to raise their children according to Quaker precepts and to ensure that their offspring entered adult relationships in accordance with strict requirements laid down by the Society of Friends. This proved no easy task as broader trends in American society gave young adults greater freedom in choosing sexual and marital partners.

The Drinkers were among those who resisted this increasingly permissive environment, retreating into their heavily regulated community of faith, but that retrenchment created serious tensions within families and especially across generations. These cultural shifts and conflicts had just as seismic an impact on individual lives as political revolution.