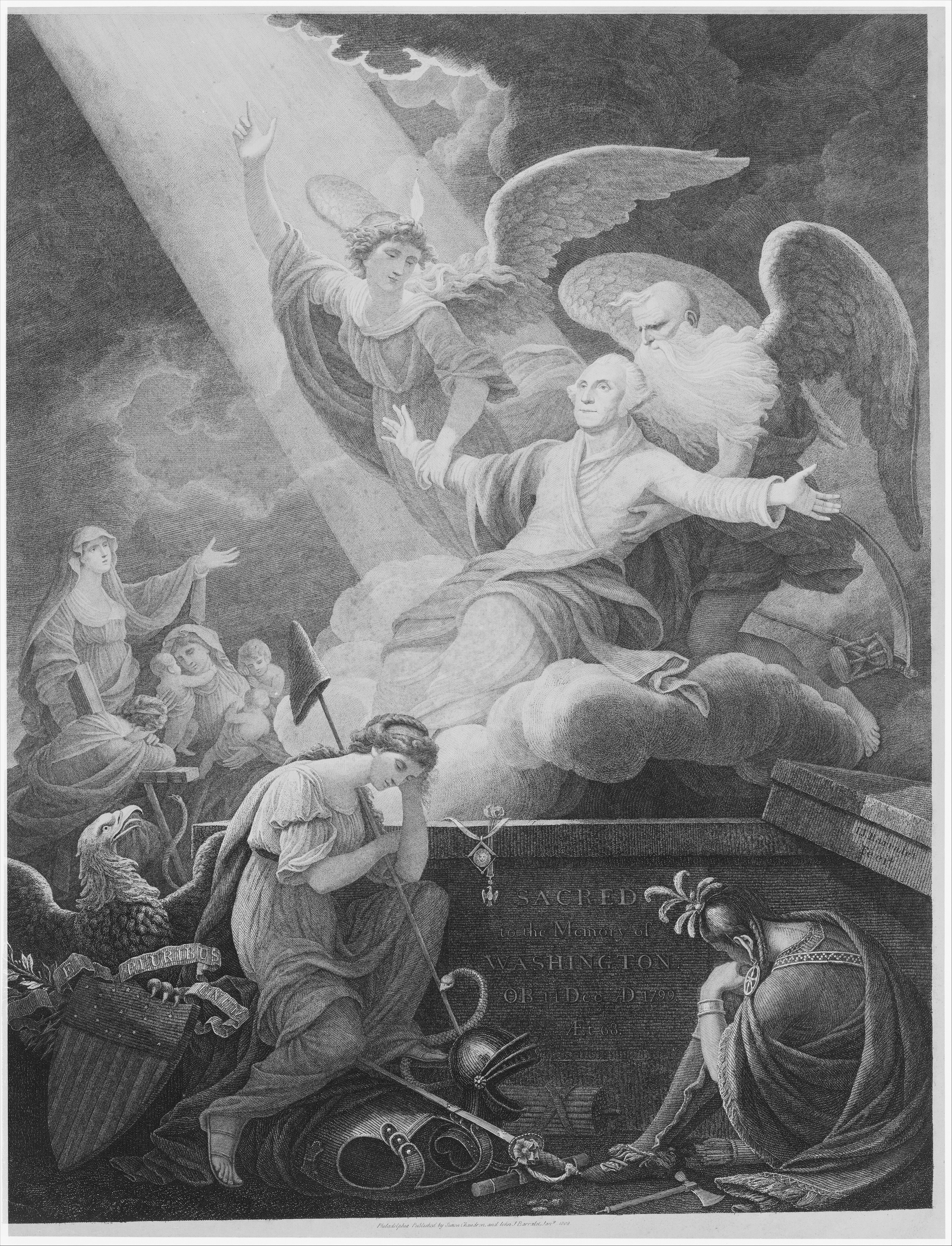

Following Washington's death in 1799, cultural and intellectual agents in early America began to transform the first president into a national symbol through books, poems, and artwork.

-

Fall 2020 George Washington Prize

Volume65Issue8

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist The Property of the Nation: George Washington’s Tomb, Mount Vernon, and the Memory of the First President, by Matthew R. Costello (University of Kansas).

Washington's death in December 1799 deeply affected the American populace. Politicians, civic leaders, and preachers participated in public commemorations and delivered countless orations and eulogies, reminding citizens of Washington's virtues and his role as the deliverer of American independence. They reminisced about the struggles that the young nation faced in its darkest moments and emphasized Washington's perseverance in war, politics, and diplomacy. His retirement from public life affirmed his reputation as a selfless leader who only wished to serve the greater good. Although his death signified a new age of uncertainty for the republic, many Americans believed that as long as Washington was remembered and emulated, he would continue to serve the country as its model citizen for future generations. In hindsight, Washington was many of these things, but he was also much more complex than his contemporaries acknowledged. Nonetheless, with the real Washington gone, intellectual and cultural agents seized the opportunity to further transform Washington into a national symbol.

With such a diverse population scattered across the former colonies, political and cultural elites labored to create a nation that could moderate these differences after the American Revolution. The intelligentsia sought to unify the populace by means of days of national celebration, imagery, poetry, music, pamphlets, and historical readers. Many nationalist movements of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries grounded their identities in a common culture, history, religion, ethnicity, or language. But Americans faced a much more difficult task in creating their own distinct nationhood.

With no ancient foundations or legends for Americans to build upon, cultural agents could only look back to the American Revolution and glorify its heroes for their rejection of monarchy and tyranny. Washington's contributions to independence made him a national hero and one of the most popular men in America; but after his death, Americans feared that without him the republic would collapse. By transforming him into a national symbol, elites hoped to inspire patriotism, solidify political control, and allay anxieties about America's ability to endure without Washington. With his physical presence gone, they attempted to employ his memory and image as a bulwark of nationhood to unite Americans and bestow lessons in civic virtue.

Studies of American nationalism have highlighted the nation-making process itself, exploring days of celebration, rituals, orations, symbols, and the myths that cultivated early nationalist sentiments. Intellectuals attempted to invent a national culture that could foster an American identity and unite the populace under the auspices of nationhood while simultaneously excluding Native Americans and African Americans because of their perceived racial inferiority. By identifying the "others" and differentiating American culture from European traditions, intellectuals sought to inspire a shared sense of belonging among white men and women. This vision for cultural harmony, however, failed to resonate with the greater American populace. Some Americans embraced nationalism, some clung to leftover colonial hierarchies and institutions and most directly challenged their designated place in the new nation.

Perhaps, as some scholars have suggested, the notion that there was ever a unified American identity was a pervasive myth rather than reality. Cultural and intellectual agents in the Early Republic believed that a nation could not exist unless a unified American identity was created and that it could not survive unless that unity was celebrated. Thus, the Revolutionary Generation promoted republicanism to enhance social, political, and national cohesion; but democratization gradually turned this form of nationhood and its icons away from republican traditions.

As the Founding receded into the past, efforts to bind Americans to republican nationhood produced mixed results. The memory of the American Revolution, considered the major cultural platform for encouraging republican nationalism, was soon contested and repeatedly redefined. While a shared historical experience, the complexity and variety of that experience had deeply different meanings for different Americans.

If there was one idea, however, one symbol that more Americans could agree on, it was Washington and his significance to the creation of the new country. His contemporaries acknowledged that he fostered a sense of patriotic cohesion among the people, so they encouraged his participation in the Constitutional Convention. After its successful ratification, they extended this reasoning, electing Washington unanimously to serve as the first president of the United States. Washington became the symbol of republicanism that elites hoped would foster national unity and allegiance to the federal government. But, much like the memory of the Revolution, he too would be recast, reimagined, and reinterpreted as Americans faced profound changes over the course of the nineteenth century.

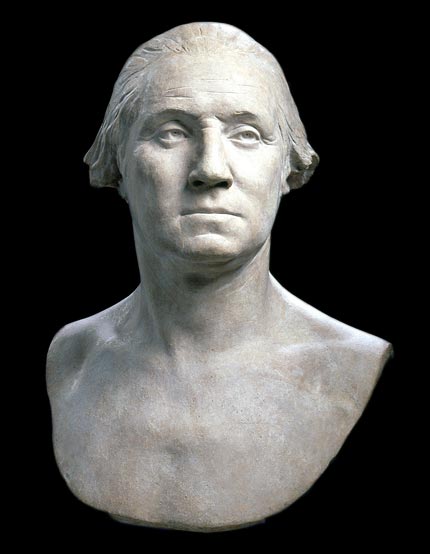

During his lifetime, George Washington obsessed about the influence he wielded and carefully considered how his speeches, correspondence, and public actions might be perceived. Once he passed away, however, Washington no longer had control over his image, and his legacy became a battleground tor political actors, religious and social pundits, and cultural mediators. Nationalist-minded elites made Washington the centerpiece of an evolving American identity, emphasizing his commitment to republican-ism and his perfection in all matters. This apotheosis imagery portrayed him as a god rather than a man, or as a statue of stoicism instead of an individual with interests, emotions, fears, or flaws. The glorification process stripped away the humanity of Washington and transformed him into a national symbol for the United States. But as the nineteenth century progressed, middling Americans craved a national hero more like themselves and less a flawless marble deity.

As time further distanced citizens from Washington's life, many amateur and professional writers produced different types of works that aimed to reconnect Americans with the Father of His Country. Motivations varied. Some wrote to inspire patriotism, some to win fame and fortune, some to bestow lessons in civility. But they all attempted to write the definitive work on George Washington and, thereby, shape the collective memory of the man. Elites and intellectuals tended to produce Washington hagiographies designed to enhance his legendary status and to serve as testaments to their shared belief in republican government. Popular writers, often with little formal education or training, labored to make Washington more relatable and interesting to the ordinary American, and the financial success and celebrity status they experienced reveal the growing popularity of a democratic Washington.

No author cultivated this creation more than Mason Locke Weems. Born in 1759 to a moderately wealthy Maryland family, Weems studied medicine and theology in London during the war and was ordained as an Episcopal clergyman. After his return to the United States in 1784, Weems served as a minister for several years, but financial hardships forced him to seek income outside the church. He traveled throughout the country as a bookseller and preacher, eventually joining literary forces with Philadelphia printer Mathew Carey in the mid-1790s. Weems began writing stories and pamphlets for publication, and when Washington died in 1799, he seized the opportunity to make his mark on the national tragedy.

Writing to Carey in January 1800, Weems exclaimed, "Washington you know is gone! Millions are gaping to read something about him.... My plan! I give his history, sufficiently minute.... I then go on to show that his unparalleled rise and elevation were due to his Great Virtues."

Weems hastily wrote a short biography of the man, and the first edition was issued on Washington's birthday, February 22, 1800. As publishers churned out new editions, Weems continually added anecdotes to the narrative, expanding the work into a more comprehensive story of Washington's life. The first editions contained very little about Washington's childhood. In the third edition, Weems devoted only three paragraphs to Washington's upbringing, mentioning that "his education was of the private and proper sort," and that in school "he was remarkable for good nature and candour; qualities which acquired him so entirely the hearts of his young companions." But, over time, Weems integrated more material into the account of Washington's formative years, hoping to inspire younger citizens to emulate Washington's moral example.

Weems's biography was an instant literary sensation, spurring new editions well into the 1820s; by the time of his death in 1825, the book was in its fortieth edition. Weems's simplistic but engaging prose made his writing accessible to literate and semiliterate Americans, and the book was relatively inexpensive. Early editions of A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington sold for 25 to 37 1/2 cents a copy, quite affordable for any American who wished to learn more about the hero. Extracts of the work were also published in newspapers and periodicals, with the aim of enticing readers to purchase the entire volume. As the biography grew in popularity and Weems expanded the text, publishers raised prices; the seventh edition in 1809 cost 87 1/2 cents. Weems sought to burnish his reputation as the preeminent Washington biographer by referring to himself as the former "Minister of Mount Vernon Parish," a congregation that never actually existed.

Many literary commentators applauded Weems's efforts to make Washington come alive for future generations, notably his portrayal of the man's everyday habits and lifestyle. One columnist noted, "It has been a subject of just complaint that in the lives of Washington, which have appeared, there has been so little of biography and so much of history; that we are not permitted to see him in the private walks of lite. Mr. Weems comes forward to supply this deficiency." By adding details about Washington's early years, Weems humanized the republican symbol, presenting him as a man who learned virtue from a young age. The most famous Weems myth, the chopping of the cherry tree, first appeared in the 1806 edition. When questioned by his father, Augustine, young George stammered, "I can't tell a lie, Pa, you know I can't tell a lie, I did cut it with my hatchet." Augustine embraced his son and praised his honesty, telling him that "such an act of heroism in my son is worth more than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of purest gold." The cherry tree myth quickly found its way into American popular culture, appearing persistently in William Holmes McGuffey's readers for schoolchildren as well as twenty-five other early American schoolbooks.

Unbeknownst to readers, Weems fabricated this touching moment between father and son. In this portrayal of Washington as a lover of truth from birth, he intended to inspire young readers to live morally and to connect Washington's childhood experiences with his religious convictions. Weems hoped that "when the children of years to come, hearing his great name re-echoed from every lip, shall say to their fathers, what was it that raised Washington to such a height of Glory?" their fathers would respond, "It was his great talents, constantly guided and guarded by religion." Historians continue to debate the depth of Washington's religious beliefs; he himself wrote very little about them, infrequently attended church, and abstained from taking Communion in public.

While some found faults with Weems's interpretation, most were complimentary of his efforts to offer more Americans the chance to learn about George Washington. One commentator highlighted Weems's storytelling ability, saying that as his work was "written in a style very fascinating to the young, it will have an extensive circulation." The multiple editions were "honorable proof, that the public curiosity is yet awake, in respect to the life and character of the beloved hero of the revolution."

As Weems's biography of the democratic Washington grew in popularity, bookstores across the country stocked up for customers. Newspaper advertisements for The Life of Washington appeared in major cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, and New York, but book agents in smaller towns, such as Newburyport, Massachusetts; Brattleboro, Vermont; Hallow- ell, Maine; Charles Town, Virginia; Cooperstown, New York; Alexandria, Virginia; Norwich, Connecticut; and Washington, Kentucky, also marketed Weems's work to local citizens. The Life of Washington was even translated into German for recently arrived immigrants in Pennsylvania. In the town of Reading, about sixty miles northwest of Philadelphia, the local German newspaper Der Readinger Adler advertised "General Washington's Leben, in Deutsch und English. For Sale at this Office, The Life of Washington, by Weems." Mathew Carey, now Weems's exclusive printer in Philadelphia, advertised "The Life of Washington, by M. L. Weems, in German. Price 1 dollar. With six engravings." As Weems's biography of Washington became part of American popular culture, Washington was transformed into the exceptional American, a man from modest origins who, by the grace of God, became America's greatest hero and political father. Later editions presented Washington as more common in his education, occupations, and even mannerisms. As a result, Washington became more akin to the American populace, no longer conceived as a deity but as an ordinary man who achieved greatness through perseverance.

Weems's fixation on Washington's private deeds and the way his humble childhood had molded his moral convictions became the most enduring means for democratizing George Washington. He panned other biographies, arguing that they never discussed "Washington the dutiful son-the affectionate brother-the cheerful school-boy-the diligent surveyor-the neat draftsman-the laborious farmer-the widow's husband-the orphan's father-the poor man's friend," only Washington "the HERO, and the Demigod." While Weems's work had many deficiencies, his criticism of fellow Washington biographers did correctly point out their neglect of his formative years in favor of lionizing him for political gain or national unity. As Weems produced more editions, he integrated more material on Washington's early life to elucidate the importance of his Christian education and upbringing in fostering his sense of right and wrong. By casting Washington not as a model of perfection but as a man who learned the attributes of virtue, piety, and humility from his father, he portrayed him as an ordinary man with strong religious principles who accomplished extraordinary things. As more and more American readers explored the mythical beginnings of George Washington, they found a man far more relatable than they ever imagined.

Weems's most powerful explanation for how George Washington rose from simple origins to national prominence came at the very end of his monograph:

And what is it that raises a young man from poverty to wealth, from obscurity to never-dying fame: What but Industry! See Washington, born of humble parents, and in humble circumstances-born in a narrow nook and obscure corner of the British plantations! Yet, lo! What great things wonder-working Industry can bring out of this unpromising Nazareth! While but a youth, he manifested such a noble contempt of sloth, such a manly spirit to be always learning or doing something useful or clever, that he was the praise of all who knew him.

Although Weems's portrayal of a democratic Washington resonated with common Americans, it sparked a backlash from intellectuals. Jared Sparks, a minister turned historian and later president of Harvard University, sought to reestablish the memory of Washington as a republican symbol and to reaffirm Washington as a model of perfection. In the 1830s, Sparks lobbied the relatives of Washington for permission to write a new biography and to publish a collection of Washington's writings. Sparks maintained that telling Washington's story required exploration and examination of the man's written words instead of reliance on inventive stories or fables. While historians today rely on the same sensible commitment to primary source materials, few would agree with Sparks's decision to judiciously edit Washington's letters. In instances where Sparks ran across "an awkward use of words, faults of grammar, or inaccuracies of style," he felt "bound to correct them." He modified misspellings, punctuation, tenses, and even entire phrases in Washington's writings and public statements, both for his biography and for the twelve volumes of Washington's writings published between 1833 and 1837. While the publications made Washington's words and thoughts more accessible, Sparks's extensive editorial work presented a highly educated Washington with excellent grammar, composition, and articulation.

Sparks explained that his scholarly endeavor sought to bring "these papers before the public" and that these edited documents were primed to reflect the "imperishable name of their author." Sparks followed two criteria in his editorial process; first, he chose documents that "have a permanent value on account of the historical facts which they contain," and second, those that "contain the views, opinions, counsels, and reflections of the writer on all topics, showing thereby the structure of his mind, its powers and resources, and the strong and varied points of his character." Not only did Sparks deliberately correct Washington's syntax but he also selected only the documents that he considered significant for publication. Sparks complained that there were just too many documents to publish, and those deemed inconsequential were left out of the volumes. While Sparks intended to make Washington's insights available to Americans, his revisions made Washington appear highly educated in thought and expression, touching upon perfection once again as the republican symbol.

This process of selective publishing also encouraged Sparks to hoard "lesser" letters for himself as mementos. He even cut up documents and gave away portions to friends, family, and acquaintances, scattering Washington's writings across the country. Sparks "was disappointed" when his associate Robert Lewis sent him a note without any Washington autographs, as it was his "intention to distribute them in Europe among eminent persons." In a letter to friend Robert Gilmore, Sparks apologized for having recently run out of "treasures" and promised to bring a "parcel of autographs" to Baltimore when he visited Gilmore next. While Sparks adamantly believed his endeavors would make Washington more accessible for citizens to study and appreciate, his processes of document handling and editing attempted to salvage Washington as the symbol of perfection. His editions became the academic standard for future studies, influencing countless historians and biographers well into the twentieth century.

With the passing of the Revolutionary Generation in the 1820s, it is possible that Sparks labored to revive the godlike Washington to ease social anxieties, but ordinary Americans continued to gravitate more toward popular works about George Washington. Weems's monograph had set the standard for writers who were willing to take more liberties to humanize, and sometimes even sensationalize, George Washington's past. George Lippard, a Philadelphia minister turned popular novelist, published two works of historical fiction that featured George Washington. Lippard rose to national literary prominence in 1844 with his horror story The Quaker Story, or The Monks of Monk Han, which featured a secret society of Philadelphia elites that practiced the dark arts by torturing victims, assaulting women, and tossing corpses into a pit beneath their mansion. Lippard's skillful prose and terrifying plots enthralled readers, and his work quickly became a sensation among the general public. One commentator noted, "It is a pity, for his fame's sake, that Mr. Lippard does not employ his pen upon some nobler subjects than those he yet has chosen .... Seek nobler themes, and loftier notes will be your reward, Mr. L" While critics often disparaged his works as vile and repulsive, Americans hungrily devoured his sensationalist novels. The Quaker City sold some forty-eight thousand copies in 1845 and another sixty thousand the following year, success that exasperated literary reviewers and intellectual writers.

As Lippard's reputation as a master of literary horror grew, he took this particular columnist's advice and produced two historical romances about George Washington. In Washington and His Generals; or, Legends of the Revolution (1847) and Washington and His Men: A New Series of Legends of the Revolution (1849), Lippard portrayed Washington as a brave and daring military commander who often rode into enemy fire, barked orders at subordinates, and rallied the frightened American soldiers with his courageous acts. Lippard did not wholly abandon his penchant for gore, as his battlefields were often littered with blood, limbs, and disemboweled corpses. Tapping into the American fascination with spiritualism, he included a mystical preacher figure that appeared after battles to offer last rites for the deceased and to laud General George Washington's actions. This religious phantom mysteriously vanishes before the next battle, but declares, "Man, chosen among men, as the leader of freemen, I speak to thee ... whose mission was joy to the captive, freedom to the slave, I bless thee, -Washington." Lippard produced gruesome yet entertaining novels, sensationalizing Washington and his actions in the fight for independence, and his literary success in historical fiction speaks to the wider effort to democratize Washington for popular cultural consumption.

Not all scholarship on Washington took such liberties with his life story or purposely distorted his writings. Washington Irving, famous as the creator of the beloved literary characters Rip Van Winkle and Ichabod Crane, published a five-volume biography of George Washington between 1855 and 1859. Already celebrated as one of America's most gifted writers, Irving was less inclined to fabricate stories or exaggerate legends. While he did invent the inner thoughts of historical figures and dialogue between them, this was common practice among historians of the time. But Irving's Life of Washington was well researched and written in accessible prose, making it one of the best nineteenth-century biographies of the man. One critic commended Irving's portrayal as more "agreeable" to the common reader, a "charming variation from the stiff, stuck-up likenesses of him, with which the public eye is familiarised." Another commentator found that "Washington in his noble simplicity and his lofty purity of soul comes before us," and he hoped that Irving would write "at least two more volumes" on the man. Irving's diligence, however, did not resonate as well with the general public, who much preferred the entertaining myths of Mason Locke Weems and the gory sensationalism of George Lippard. The creative liberties they took made their histories financially successful and also more attractive to the masses, and these stories became landmarks of American popular culture.

As national politics became more divisive in the 1850s, many Americans looked nostalgically to the past as a way to inspire unity. George Washington Parke Custis, Washington's step-grandson and the last living relative who had had a close relationship with George Washington, offered his own biographical perspective to enlighten and bond Americans. Born on April 30, 1781, to John "Jacky" Parke Custis and Eleanor Calvert, George was named after his famous step-grandfather. Later that year his father, who was serving as aide-de-camp to General Washington at Yorktown, contracted an illness and died. Eleanor Calvert decided to leave the two younger children, Eleanor and George, with George and Martha at Mount Vernon, taking her elder daughters Elizabeth and Martha with her into widowhood. George adored Eleanor, or "Nelly" as he affectionately called her, but George Parke Custis, also known as "Wash," was a constant source of vexation.

Wash and Nelly were the children that George and Martha never had, and they were inseparable from their adoptive parents. While Martha taught Nelly the social customs of the Virginia gentry and household management, George attempted to motivate his lethargic teenage step-grandson. Hoping to give Wash the formal education he himself never had, Washington sent him to Germantown Academy, St. John's College in Annapolis, and Princeton University. But Wash never acclimated to the intellectual rigors of college and spent most of his time writing short stories and poetry. While letters between the two were always amiable, Washington soon lost patience with Wash. "With respect to your Epistolary amusements, I had nothing further in view in the caution I gave you, than not to let them interfere with your studies, which were of more interesting concern," wrote an irritated George in July 1797.

When George Washington Parke Custis turned twenty-one in 1802, he inherited extensive landholdings and slaves from the estates of his father John and his grandparents George and Martha. As Wash settled into his new life as an affluent Virginia aristocrat, he began constructing Arlington House, a grandiose mansion in the Greek Revival style, filled with George Washington memorabilia. As a pastime, Custis became an orator, delivering his first public speech at the Washington Society's Fourth of July celebration in 1804. And in closing remarks to the "Arlington Sheepshearing Institution" in 1808, he congratulated those in attendance on a fine year of livestock production, but devoted more attention to the "memory of General Washington." Thus began a long and successful career as George Washington's personal publicist, a role that George Washington Parke Custis felt he was born to play. As Jared Sparks worked to compile Washington's writings in the 1830s, Wash frequently corresponded with him, even inviting him to Arlington House several times to discuss the editorial process, the selection of documents, and their future publication.

Eager to offer the American populace his own semi-democratic version of Washington, George Washington Parke Custis began composing Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington in the 1850s. He had excerpts printed in newspapers and periodicals, but his daughter Mary Custis Lee did not publish the final version until after his death in 1857. In Recollections, Custis offered readers a much more nuanced portrait of Washington; and, as the last living family member who knew Washington personally, his text became a sensation on the eve of the Civil War. Custis gave the American populace a Weems-like presentation of Washington, detailing his habits, manners, and daily regimens based on his personal memories. He strove to present a Washington who was more modest and simple, less one of the Virginia elite and more a middling but proficient farmer. Washington rose early, dressed, visited his stables, and worked in his study until breakfast. An enslaved valet prepared his clothes, which "were made after the old-fashioned cut, of the best, though plainest materials." A simple meal of "Indian cakes, honey and tea" was his favorite morning meal. He carried an umbrella during his rides about the estate, but this was not "an article of luxury, for luxuries were to him known only by name." At exactly quarter to three, "the industrious farmer returned," and Washington ate heartily at three o'clock. He was "not particular in his diet," and he often "drank a homemade beverage." He often spent the afternoon in his study, and later joined family members for tea and conversation before retiring to bed around nine 0’ clock.

Washington in retirement certainly appeared more ordinary than most expected, but Custis was not immune to the legends and stories regarding Washington's stature or physical strength. In one anecdote, a young Washington was reading under a tree while some companions were tussling in a wrestling match. When the champion called forward any challengers, Washington hurled him to the ground and "leisurely retired to his shade." According to Custis, Washington once threw a stone across the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg and another "over the Palisades into the Hudson." On another occasion he joined a "pitching the bar" competition between younger men, and proceeded to hurl the missile "beyond any of its former limits." In Custis's estimation, Washington's "personal prowess, that elicited the admiration of a people who have nearly all passed from the stage of life, still serves as a model for the manhood of modem times." It seemed that Custis was trying to strike a balance between the popular Weems version of Washington and the republican symbol, but this made his recollections a peculiar mix of personal observations and legendary tales.

In addition to stories about his grandfather's life, military battles, and experiences as president, George Washington Parke Custis also used the Recollections to declare that Washington and his remains belonged to all Americans. Custis had supported the federal government's previous attempt to remove the body in 1832, and he took this opportunity to articulate his opinions to readers. "[Washington] no doubt believed that his ashes would be claimed as national property, and be entombed with national honors," he wrote, adding that failure to do so had "agitated the American public for more than half a century." After Washington's death, Custis said, Congress had been right to request his remains, and he praised his grandmother Martha for consenting on the condition that they be buried together. Martha "had the right, the only right" to allow such memorialization, and she granted it "to the prayer of the nation as expressed by its highest authority." By using the phrase "national property," Custis reaffirmed the popular belief that Washington belonged to the nation in body, mind, and spirit.

While many writers produced factual and fictional versions of Washington's life, cultural agents embraced Weems's Washington and used poetry, music, and imagery of his tomb to reinforce the idea that the humble Washington was the property of the nation and, thus, belonged to all Americans. In a performance of one poetic address, "students of the Georgetown College" rhythmically revered the man "who snatched from slavery's hand her iron rod / Who trampled down the Britons' tyrant laws / And nobly fought and bled in Freedom's cause." They were heading to Mount Vernon, declaring that "we also come to shed a tender tear / Upon his grave, whom ev'ry heart holds dear," hoping that Washington would show these free men "how to live, and how to die." Ebenezer Bailey, a Massachusetts native and Yale University graduate, won a poetry competition to commemorate Washington's birth in 1825 for his ode "Triumphs of Liberty." Bailey wrote, "Though no imperial Mausoleum rise / To point the stranger where the hero lies / He sleeps in glory. To his humble tomb / The shrine of Freedom, pious pilgrims come / To pay the heart-felt homage, and to share / The sacred influence that reposes there ... The land he sav’d, the empire of the Free / Thy broad and steadfast throne, Triumphant Liberty!" Bailey eloquently and metrically portrayed Washington's legacy as a man of the people and as the deliverer of an empire destined for greatness.

Visitors to Mount Vernon often shared their experiences in published accounts, but for aspiring poets and writers, the tomb served as a source of inspiration for artistic pursuits and commemorations of Washington's modesty. "FMB," in his ode "At the Grave of Washington, at Mount Vernon," exclaimed "and thou art here!-this is thy tomb / This lone and nameless grave / Unmarked, save by the wild Hower's bloom / Or trailing cedar's wave ... The simple turf heaped on that spot / As well might 0' er a peasant rot," The author encouraged Americans to visit Washington's tomb "for a father lies below / A parent to thy parents, he / Shall not his cor[p]se George then claim from thee / Thy tear-drops' deepest flow?" Lydia Sigourney, a popular nineteenth-century poet and advocate of women's education, published a poem entitled "Washington's Tomb" in 1837. She promoted similar attributes of Washington, asking readers to "meet here, as brothers meet / Round a loved hearth-stone / Meet in a communion sweet / Here, at your father's feet, WASHINGTON!" Sigourney also wove in motifs of republican motherhood: "but when the mother at her knee / Teacheth her cradled son / Lessons of Liberty / Shall he not lisp of thee / Washington!" For Sigourney, Washington was the means to end "discord" or "mad disunion," a reflection of the changing partisan atmosphere, and her words were intended to unite "brothers" around their shared political father. These works suggested that Washington had not only given America its freedom but also served its citizens as their political father. By visiting the humble tomb, Americans could thank Washington for bestowing both freedom and democracy on the people.

Harvey Rice, a lawyer and Democratic state senator of Ohio, produced an entire volume of poetry entitled Mount Vernon and Other Poems that linked Washington with the advent of political democracy. In a thirteen-page poem, Rice offered readers a romanticized journey across the estate, through the mansion and gardens, down to Washington's final resting place. Rice wrote, "Though but a lowly shrine / There grateful hearts delight to pay / Homage to Freedom's son divine / The mightiest in the fray / The mightiest in his country's darkest day!" Washington had fought "for Human Rights, though traitors sneered," and he was "sworn to defend the rights of man," even casting aside the offer of a crown "to bide the people's sway." In Rice's estimation, "his name the oppressed shall breathe, and dare / With well-directed blade / Reclaim their holiest rights, too long delayed." Washington represented the freedom that democracy bestowed on all men, regardless of their class, status, or place in American society. This, according to Rice, was his greatest contribution to America and was central to his legacy.

Popular culture also celebrated the memory of Washington and his simple tomb through nineteenth-century musical compositions. "Washington's Tomb Ballad" was frequently performed at tomb visits and commemoration ceremonies. The song, "written by T. P. Coulston, composed by Carrol Clifford, arranged by C. Everest," as noted on the sheet music, began, "hopes of freemen e'er will cluster, Where Potomac's water glide; Where beneath the shades of Vernon, Sleeps our noble country's pride," followed by the chorus, "Let no desecrating footsteps E'er that soil of freedom tread." The second verse followed: "Hearts of freeman, ever beating / Funeral dirges round that grave / Stand as sentinels forever / And those hearts are strong and brave ... For they stand as one united, Death or freedom sworn to share." Washington's name was incessantly connected to free men, those who owed their political rights to a man who, in fact, had actually dreaded the growth and spread of democracy.

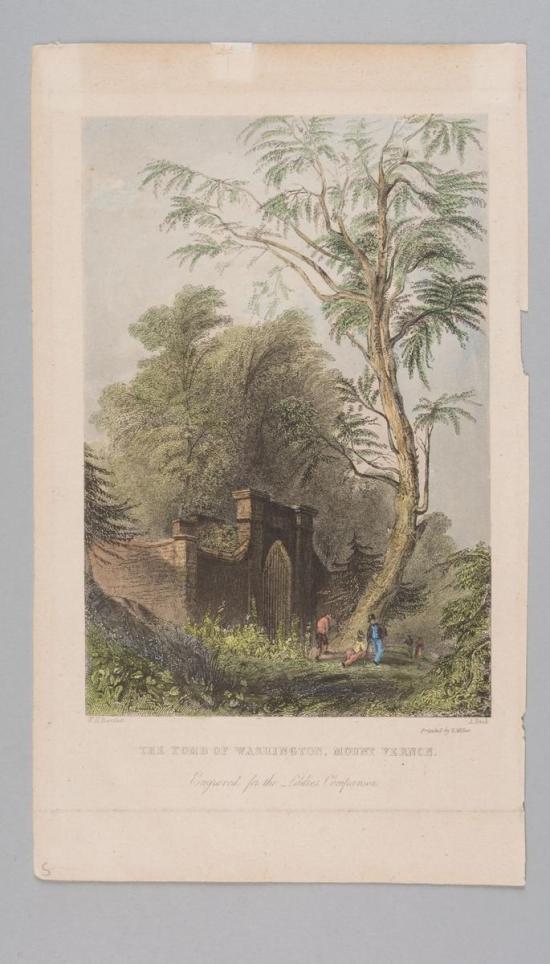

Beyond biographies, poetry, and musical compositions, the imagery of Washington's tomb-drawings, engravings, lithographs, and paintings-visually affirmed the modesty and humility of Weems's democratic Washington. While formal portraits of Washington never deviated very far from the likes of Gilbert Stuart, Rembrandt Peale, and John Trumbull, Washington's tomb attracted many amateur landscape artists. For ordinary Americans, such imagery was their primary means to visualize and experience Washington's grave; and the accounts of those fortunate enough to visit the tomb in person reaffirmed the humble traits that Weems's Washington embodied.

While some visitors balked at the modesty of Washington's final resting place, others appreciated it as further proof that Washington was forever uninterested in hero worship. One gentleman described the grave as "very humble; and it seems scarcely possible that so mean a place can contain so great a man." Another visitor in 1827 was surprised that there was "no monumental marble ... no sculptured urn or consecrated bust," but "all was simple and natural, but not less affecting than mausoleums and sarcophagi." This writer believed that, although "the gratitude of the nation should indeed raise a monument," to the average traveler "this plain grave ... was a more delightful spot for contemplation, than the shade of a pyramid or the summit of a column." The depiction of the tomb by self-taught English immigrant artist Joshua Shaw, printed by Mason Locke Weems's publisher Mathew Carey in Picturesque Views of American Scenery, embodied these observations, as he portrayed the site as a peaceful coexistence between the grave of Washington and the Virginia landscape. The austerity of such a tomb was not lost on visitors, and its appearance made Washington seem less aristocratic and more like a common man.

As Americans' love of nature and landscape imagery grew, Washington's tomb became one of the most frequently drawn scenes in American popular culture. One visitor remarked in 1841, "I stood in front of the tomb, surrounded with the solemn stillness of the forest, undisturbed but by the murmurings of the waters of the Potomac .... I felt a more deep and mournful melancholy than I ever experience[d] before." Everything seemed to "inspire the mind with the deep solemnity of the place, and the utter vanity of all human ambition," he wrote in the Hudson River Chronicle. The similarly, named Hudson River School, a leading nineteenth-century art movement with nature as its focal point, mirrored such imagery. Hudson River artists illustrated a harmony between humans and nature in grand landscape paintings, weaving together themes of exploration, settlement, and discovery as Americans pushed westward. Their depictions of the country's natural beauty and sublimity were both aesthetically pleasing and representative of a growing cultural appreciation of nature that was seen in literature, religion, and spiritualism. Whether artists intentionally played up these themes in their portrayals of Washington's tomb is unknown, as they may simply have been capturing the scene in question. But their paintings and sketches illustrated the beauty of nature surrounding Washington's grave and the modesty of his tomb, which paralleled the themes of the Hudson River School and contributed to this new form of American popular culture. As important as natural sites were to fostering national identity, so too were historically significant places of remembrance.

Tomb imagery was not limited to print or lithographic forms. Painters, armed with these mass-produced images, began to re-create Washington's tomb in their own artistic medium. William Matthew Prior, an American artist with over fifteen hundred paintings attributed to him and his proteges, painted multiple versions of Washington's tomb. Prior was known for his folk portraits and landscapes; because he had no formal training, his work was not considered to be up to the standards of a classically trained artist. Prior became one of America's most famous folk painters by painting portraits of men, families, and children. His work, along with the portraiture of his brothers-in-law Nathaniel, Joseph, and Sturtevant Hamblin, gave rise to what was called the Prior-Hamblin School, which includes paintings that traditional art critics consider naive in interpretation and execution. His use of longer brush strokes allowed him to avoid painting intricate details, a technique that detractors labeled primitive as compared to European styles. Regardless, Prior and his peers fashioned a plethora of portraits and landscapes, offering a distinctly American folk style that ignored the stylistic traditions of the Old World. Prior drew a series of images of Washington's tomb dating back to 1840, and whether his medium was ink, chalk, charcoal, or oil-based paint, Prior stayed relatively consistent in his portrayal of Washington's modest tomb.

After the American Revolution, the elite elevated George Washington as an icon and a symbol of republicanism in an effort to inspire national unity. But instead of national unity, there was competition among political parties, fraternal organizations, and the many Americans who were left on the margins of the nation-making process. As political democracy incorporated more middling Americans into the folds of the nation, the memory of Washington was transformed to greet them. While the image of Washington as demigod never disappeared, a democratic Washington-described as a frontiersman, surveyor, proficient farmer, and humbly entombed citizen-emerged to shape the collective memory of Americans. This Washington resonated with the populace because these occupations and attributes reflected the origins, lifestyles, and struggles of most Americans. His modest education and common roots spoke volumes about his rise to prominence, and his example gave support to the idea that ordinary Americans could aspire to and achieve greatness as well. This imagined connection between Washington and free men was fostered by writers, poets, artists, and musical composers, all of whom recast Washington to fit the rapidly changing political landscape of the nineteenth century.

Despite the political disagreements over the proper memorialization of Washington's body, the memory of Washington had already entered popular American culture, forging a link between Washington and the people, a link that cultural agents exploited, some to promote national unity, some for pecuniary gain. The tomb had already become a place of veneration, and, as poetry, music, and imagery highlighted the link between Washington and the nation, more Americans embraced the Mason Locke Weems version of George Washington. Weems's creative narrative made Washington more relatable to the average American, and poets, composers, and artists played up these humanizing traits, reinforcing the populist Washington as a man of unassuming origins, simple tastes, and learned virtue. The effect of these artistic endeavors, along with the countless visits made to Washington's tomb, was to foster a Washington of the people and by the people. It was this version of Washington that captivated Americans and fostered the idea that Washington and his memory belonged to the nation. Further proof of this cultural transformation and its ongoing impact could be found on a small homestead on the Indiana frontier. A young farm boy with no formal education but with a fascination for books opened Weems's Life of Washington, reading it diligently from cover to cover. For the remainder of his life, he maintained that this story shaped his views on self-improvement, honesty, leadership, and civic duty to his fellow man and country. That boy was Abraham Lincoln.