Stationed near Nagasaki at the close of the war, a young photographer ventured into the devastated city, and stayed for months

-

June/July 2005

Volume56Issue3

I had trained at Parris Island thinking, I was going to the Pacific to fight the Japanese or at the very least to photograph American troops fighting the Japanese. That whole time it had been drummed into us Marines how fiendish the Japanese were. We knew the story of the Bataan death march by then. We knew about the kamikaze pilots crashing into our ships. We knew the Japanese would never surrender.

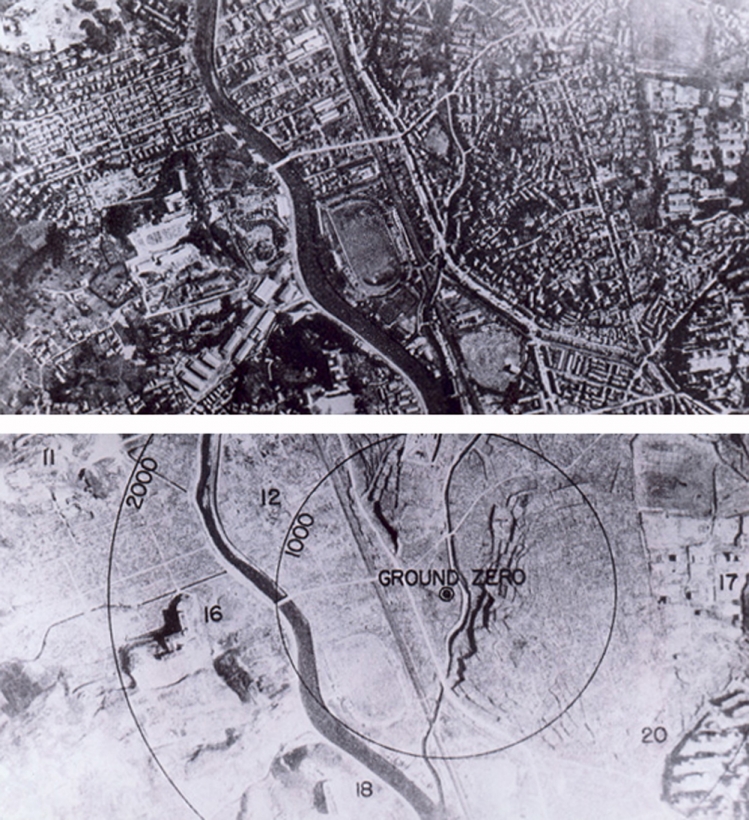

We knew all that until August 6, 1945, when Harry Truman went on the radio to announce that a new bomb had been dropped on a Japanese city named Hiroshima. Truman called it “a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.” A few days later a second bomb exploded over Nagasaki.

Then, in a literal flash, it was over. The Japanese hemmed and hawed for a few days and surrendered. On August 28 the first occupying troops entered the country. My unit was sent about 10 miles from the city of Nagasaki, on the island of Kyushu.

None of us knew what we would find there, General MacArthur and leaders in Washington had tried to limit press access to both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the day of the surrender Wilfred Burchett of the London Daily Express traveled 21 hours by train from Tokyo to Hiroshima and reported through a Japanese news agency about radiation sickness. But he was the only one.

Naturally we were curious about the effects of the bomb. My warrant officer told me to go take some pictures, so one day I just walked the whole 10 miles. Another photographer named Larry Johnson went with me. He was kin to Gen. Lewis Hershey, the man who had run the peacetime draft.

The road into Nagasaki was long, wide, and unpaved. It was hot that day, and humid, and we were surrounded by flies and mosquitoes. We really had no idea where we were going, so when we finally saw somebody, a Japanese farmer, we took out our language book and tried to ask him where the city was. He answered back, gesturing sadly. We never did know what he was saying. Maybe we didn’t need to.

I knew by the smell when we were getting close. If you’ve ever smelled a dead dog by the side of the road, you’ll have an idea of what it was like. Flies and maggots were everywhere. The smell started a couple of miles before we saw anything.

Nagasaki was hard to see because it was surrounded by a series of ridges. As we got closer, it was not just the smell that grew overpowering but the silence. There was nothing: no birds, no wind blowing, nothing to make you think there had once been a real city here. One of the first people I saw was a man who said, “I live over on that mountain, just at the top. You have to go to the school over there.” He pointed down the valley and up the ridge on the other side. I asked him why, and he said, “I want you to see something.” He spoke in Japanese, but I managed to understand some of it.

I started walking, looking back to see if he was following me, but he wasn’t. I kept going right through the heart of town, or what had been the heart of town. There were piles of brick everywhere and scorched wood. There were no trees or vegetation. When I reached the top of the ridge, I saw a tiny schoolhouse made of cement block, most of it still standing. I walked into the schoolroom, and there they were, all still sitting at their desks, 30 or so kids burned to cinders. When I got back outside, I noticed that the ground leading up to the school had somehow been sheared off. The hillside must have forced the blast upward, sparing the building but incinerating everybody inside.

Often what struck me was not what had been destroyed but what had been spared. One day I came across a beautiful paved street. Most of the streets were so filled with debris that I couldn’t walk down them, but this one was so clear that it was like walking a straight path through Hell. I remember taking a photograph of three girls holding a dead body. They didn’t want their picture taken; they thought it would steal their souls or something.

I ran into children playing baseball and women washing their clothes in a pool of water. When I brought out the camera, they waved me away. I didn’t get one picture. That night, back at headquarters, I racked the camera bellows all the way out, took the prongs off, and put in 10 chocolate bars and several sticks of Juicy Fruit gum. After that, whenever I went looking for pictures, I would call out “chocoletto” and the kids would come running.

The hardest thing at first was just finding somebody living. In the beginning the only people I saw were those who had fled town before the blast and had just come back. Eventually more people would show up and poke around what had been a house or a building. Hardly anybody said anything. With the exception of the men in my unit, I saw very few other American Army or Marine personnel. People wanted to stay away from what we had done.

Down near the center of town somebody had created an airstrip. The entire area was just flat. Somebody put up a sign that read ATOMIC-FIELD. Planes would land there. That’s where I would meet my plane, give the pilot my film packs to be developed, or pick up supplies like K rations. The K rations were handy to give the kids, along with the chocolate and cigarettes. Hell, I liked K rations.

One day I met a Japanese photographer who had shot three pictures of the bomb explosion. I asked him why he hadn’t shot more, and he answered, “It was too horrible.” I got to be friendly with him, and he told me, “Be careful with your negatives. The military will take them. They took my film, they took my cameras, they took every record I made.”

The Marines had issued me a camera back in the States. Then, in the best bureaucratic tradition, they issued me another one. I put them both in my trunk and kept them there. A Speed Graphic is heavy — it must weigh six or seven pounds — but its 4-by-5-inch negatives make really sharp enlargements, better than any 35-millimeter camera. Carrying one Speed Graphic by shoulder strap was bad enough. But since I had to send one set of negatives to Pearl Harbor to be developed and then to Washington, I hauled both cameras with me. When I got a shot I wanted, I usually took two pictures, one for the Marines and one for me.

I had a room in the barracks set up as a darkroom. I had my own trays, my own chemicals. Since I could not control the temperature of the water, which needs to be 68 degrees, I couldn’t develop by the clock. I had to do it by inspection. I got to where I could use the reflected light of the full moon to examine the negatives without fogging them. I’d put a negative in the chemicals for a while, take it over to the window, open the curtain and inspect it, take it back to the tray again, and so forth. After I was satisfied with the exposure, I would rinse the negative, put a hole in one corner, and hang it on the branch of a tree to dry. The guys in the barracks thought it was all official.

I took a picture of three little kids with a wagon. I don’t know where they got it. Things like that were generally destroyed or confiscated. They may have made it out of an old box and wheels. I had no candy to give them but I did have an apple. I gave it to the biggest, who almost tore my hand off grabbing for it. He took a couple of bites, then gave it to the next one, who took a bite and passed it on. I could hardly watch; as soon as the skin of the apple was taken off, black flies descended on it. The kids ate the skin, the core, the flies, everything.

One day I saw a line of people standing outside next to a desk from a destroyed building. Their clothes were burned; their faces were burned. A guy was sitting there writing, taking down lists of names. The people in line were pretty sad-looking; sometimes, if they had been facing sideways when the bomb exploded, only one side of the face would be burned.

I often get asked about the number of bodies. There were no bodies; there were bones. What was left of the flesh, if it survived, the crows got. The crows hated to be shoved away. I’d yell, “Get out of here, yah, yah!” The crows made it impossible for the planes to land sometimes.

I don’t think average Japanese citizens knew exactly what had happened. They had seen something in the sky, an airplane, and all of a sudden the bomb went off. With the language difference, they couldn’t say much to me except in sign language or broken English. They did not appear to be resentful, there was no “Yankee Go Home.” They just seemed stunned, numb.

I acquired a horse, which I named Boy. I had been riding in a jeep with Johnson outside the city and I saw a farmer who had horses. There was a big one with white hair, and I pointed to him. The farmer looked at us and said, “Boy, Boy, Boy. Big horse. You pay?” I ended up trading cigarettes for the horse. He wanted 100 packs; we compromised on about 20.

For the next seven months I rode that horse, strapping my heavy cameras to the saddle. Boy not only made it easier to get around the city, he offered a good vantage point for my photographs. Sometimes I wouldn’t even dismount to take the picture. And, riding Boy, I didn’t have to step on the bones when I walked around town.

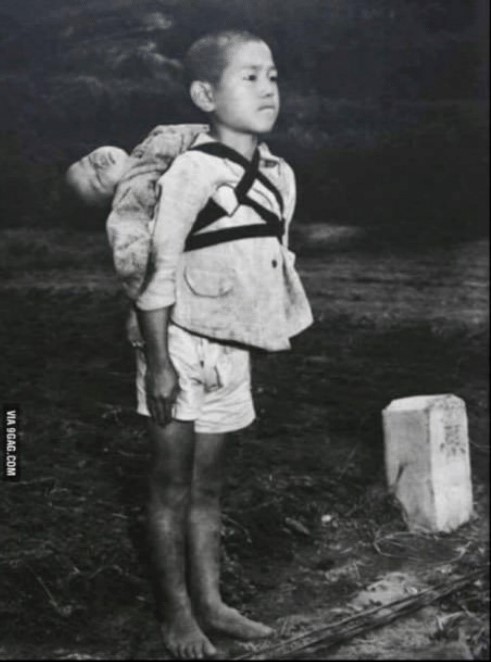

I met a boy about 12 years old who had lost a leg and walked with a crutch. I could see that the crutch was too big for him. I told him to come to me and sit down. When I took out my knife, he protested, “No, no, no.” “Wait a minute,” I said. “It’s O.K.” I took about six inches off the bottom and gave the crutch back to him.

He walked about 10 or 15 feet, turned around, and flashed a big grin. “O.K., O.K.,” he said. We became good friends.

For a while I lived in an abandoned house and kept Boy inside with me. The Japanese would eat horses, so I was careful; I asked my friend One Leg to feed Boy, walk him, and keep an eye on him. One day near the end of my time in Nagasaki, One Leg didn’t come, so I went to his grandmother’s house. She answered the door, and I asked for One Leg. She pointed to her leg, then put her head like she was sleeping and pointed up. I couldn’t believe it, but apparently he had died from infection. The grandmother ushered me inside the house, where the entire family was kneeling facing a candlelit wall. I knelt beside them at their memorial for One Leg. Finally the grandmother got up, went to the back of the room, and returned with what I thought was a sword. She presented it to me: One Leg’s crutch.

In March of 1946 we were called to attention outside the barracks.

“You guys are going home tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow,” I thought. “What am I going to do with all my negatives?”

There was supposed to be a final inspection the next day at 7:00 A.M., and I kept thinking about the Japanese photographer whose work had been confiscated. Then it came to me. I had several large boxes of photographic paper marked “Do not expose to light. Do not open.” I put all the negatives into the boxes and sealed them. I hoped they would skip me during inspection, but they came right up to me.

“You have quite a lot of equipment there, Sarge.”

“I need it.”

“Why do you need it?”

“I’m a photographer. I take pictures and print them. I need film, chemicals, and paper.”

“Where’s this stuff going?”

“Pearl Harbor.”

“Well, you sure have a lot.”

“I need a lot.”

I don’t know what would have happened if they had searched my belongings and found the negatives. They would have confiscated the pictures, and they might even have sent me to the brig. No one on our side quite knew how to react to the atomic bomb, whether to be open and proud about it or secretive and ashamed.

Now that it was time to leave Japan I found I didn’t want to go. Hell, I was a kid, and horrible as all this was, I was having the time of my life.

But I came home, went to work for the government, and forgot about it all, or at least I thought I did. Years later, many years later, the nightmares began: the voices of the children, the endless stretches of rubble and bone, the stench. Over and over again. The voices were always pitiful, always begging. Yet they were accusing too.