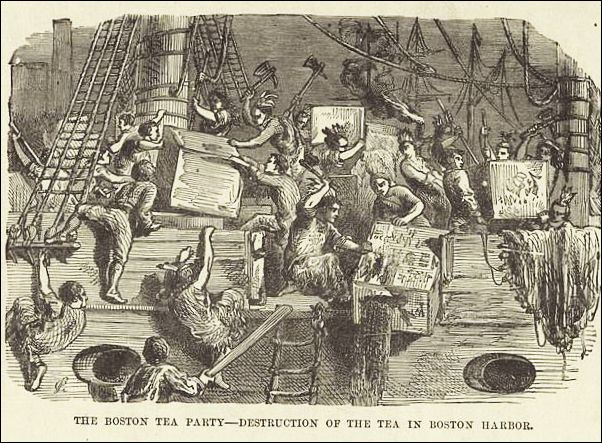

Badly disguised as Indians, a rowdy group of patriotic vandals kicked a revolution into motion

-

Winter 2010

Volume59Issue4

On the evening of December 16, 1773, in Boston, several score Americans, some badly disguised as Mohawk Indians, their faces smudged with blacksmith’s coal dust, ran down to Griffin’s Wharf, where they boarded three British vessels. Within three hours, the men—members of the Sons of Liberty, an intercolonial association bent on resisting British law—had cracked open more than 300 crates of English tea with hatchets and clubs, then poured the contents into Boston Harbor.

News of the “Boston Tea Party” quickly spread throughout the colonies, and other seaports soon staged their own tea parties. While tensions between the Americans and the British had simmered for the past several years, there had been few acts of outright rebellion. The tea party lit the smoldering coals of discontent and ignited events that would lead to rebellion, war, and, finally, independence.

The first bloodshed of the Revolution had occurred nearly three years earlier, on March 5, 1770. A continual source of tension was the taxes levied by the British government on the colonists. Although British Prime Minister Lord North tried to placate the colonists with a pledge of no new taxes from London, on March 5 a mob of radical Americans, unaware of the announcement, had attacked the customhouse in Boston, prompting a confrontation with British redcoats. The crowd had begun to throw hard-packed snowballs at the British sentries guarding the customhouse. Goaded beyond endurance, the soldiers began to fire, killing five people and wounding several others in what came to be known as the Boston Massacre.

But North’s concessions had dampened the rebellious attitude that had been spreading through the colonies, causing a backlash among moderates who believed that the Sons of Liberty presented a greater danger to America than did British taxes and troops. By October 1770 Boston’s merchants announced that they would no longer honor the patriots’ boycott of British imports, and it looked as though the flames of rebellion had been snuffed out. Although some of the more ardent revolutionaries kept in contact through committees of correspondence that issued statements of colonial rights and grievances—Samuel Adams pledging that “Where there is a Spark of patriotic fire, we will enkindle it”—no more significant incidents of violence would occur until late 1773.

During this reprieve North became more concerned with Britain’s economic policies than with colonial discontent. The behemoth of British international trade, the East India Company, teetered on the verge of insolvency. Because many leading British politicians were company shareholders, saving it was of particular concern to Parliament. One potential solution seemed at hand: the company’s London warehouse held more than 17 million pounds of tea. If these stores could be sold, the East India Company might survive. North concocted an ingenious plan to sell the tea in America at much lower prices than those offered by smugglers such as John Hancock, who brought in goods from Dutch possessions in the West Indies. Even with the British tax, the company’s tea would still be cheaper than any imported from the Dutch. If everything went according to plan, the Americans would concede England’s right to tax them in order to get inexpensive tea, and the East India Company would be saved in the bargain.

But things did not go according to North’s plan. The Sons of Liberty believed it reeked of subterfuge, an underhanded attempt to force the colonists to continue to pay taxes. Hancock, who hated the British as much as he loved his profits, finally saw a chance to strike at the former while preserving the latter. On December 16, 1773, he and Samuel Adams directed a group, most of whom were members of the Sons of Liberty, to board the British tea ships and destroy their cargoes.

London was shocked and angered. Parliament bristled with loose, vengeful talk of sending a large expeditionary force to America to hang the rebels, level the settlements, and erect a blockade in the Atlantic to starve the ungrateful colonists. A few voices of reason, such as Charles James Fox and Edmund Burke, rose in the House of Commons to endorse punishing those directly involved but warning against a blanket indictment of all Americans.

In March 1774 Parliament passed the Boston Port Act, mandating that the city’s harbor be closed until the colony paid Britain 9,570 pounds for the lost tea. (The bill was not paid.) A firestorm of protest exploded in the colonies, where radical leaders sneered at the new laws as “the Intolerable Acts” or “the Coercive Acts.” Sympathetic demonstrations took place in many cities. Samuel Adams demanded action from the committees of correspondence in the form of a complete embargo on British goods. In Virginia Thomas Jefferson burst upon the revolutionary scene when he published his Summary View of the Rights of British America , which took issue with Parliament’s right to legislate colonial matters on the grounds that “The God who gave us life, gave us liberty at the same time.”

On September 5 representatives from every colony except Georgia met in Philadelphia at what came to be known as the first Continental Congress. Radicals called for Samuel Adams’s trade embargo, while moderates led by John Jay of New York and Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania supported a strongly worded protest. All agreed that some form of action had to be taken. On behalf of the radicals, Joseph Warren of Massachusetts introduced the Suffolk Resolves, declaring the Intolerable Acts to be in violation of the colonists’ rights as English citizens and urging the creation of a revolutionary colonial government. Much to his surprise, the resolves passed, if just barely. George III was infuriated at the whole business. To him, the very calling of the Continental Congress was proof of perfidy. “The New England governments are in a state of rebellion,” he told North.

Gen. Thomas Gage, the British commander and now Massachusetts governor, received orders to strike a blow at the New England rebels. Gage learned of their whereabouts and sent troops to seize them and then destroy the supply facility at Concord. But that night Boston silversmith Paul Revere rode the 20 miles to Lexington to warn the radical leaders and everyone else along the way that the British were coming. When British troops reached the town on April 19, 1775, they encountered an armed force of 70, some of them “minutemen,” a local militia formed by an act of the provincial congress the previous year. Tensions were high and tempers short on both sides, but as the Lexington militia’s leader, Capt. John Parker, would state after the battle, he had not intended to “make or meddle” with the British troops. In fact it was the British who were advancing to form a battle line when a shot rang out—whether it was from a British or colonial musket, no one knows to this day. At the time neither side realized it was the first blast of the American Revolution.

The lone shot was followed by volleys of bullets that killed eight and wounded 10 minutemen before the British troops marched on to Concord and burned the few supplies the Americans had left there. But on their march back to Boston, the British faced the ire of local farmers organized into a well-trained embryo army, which outnumbered the British five to one and shot at them from every house, barn, and tree. By nightfall total casualties numbered 93 colonists and 273 British soldiers, putting a grim twist on Samuel Adams’s earlier exclamation to John Hancock, “What a glorious morning for America is this!”

A declaration of independence was no longer a pipe dream but a revolutionary plan in the making. From the Tea Party to the bloody fields of Concord, the thirteen colonies had proved that direct action was the surest way to free themselves from British tyranny.