Important new information on the central figure in the early American republic has surfaced with the publication of new volumes of Jefferson's journals and correspondence.

-

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2017

Volume62Issue4

In late autumn of 1793, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson was in Germantown, Pennsylvania, then the nation’s temporary capital. A devastating outbreak of yellow fever had driven the government, including President George Washington, out of the capital, Philadelphia, to escape the horrific epidemic, whose origin was a mystery to all. Jefferson had not, in fact, been a part of the exodus. He had decided to leave Philadelphia in the winter of 1792, well before the outbreak. Perhaps he had grown weary of city living or, more likely, wished to find respite from the scene of his metaphorical death match with Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, his chief rival in Washington’s cabinet. The two men had very different visions about the way the new country should progress, and Washington sided with Hamilton.

Jefferson had taken residence in a house along the Schuylkill River in April. After a brief sojourn at his home, Monticello, he moved to Germantown knowing that he was in his final days in the administration. When he lost the battle with Hamilton, he gave notice of his decision to resign his post. After some difficulties obtaining lodging in the town newly crowded with refugees, he was able to find a home. It was from this place, and against this backdrop of troubled and disorienting times, that Jefferson wrote to his friend Angelica Schuyler Church in the waning days of November.

Jefferson and Church had first met in Paris on the eve of revolution, while he was serving as minister to France. When he wrote to her from Germantown, she was still in London, but she had written to him of her impending return to America and with news of mutual friends they had known there. The marquis de Lafayette had been jailed (which Jefferson knew). Madame de Corny, who ran a salon that Jefferson often frequented, had lost her fortune. Maria Cosway, with whom Jefferson had had some sort of dalliance, had entered a convent. Jefferson reassured Church that efforts were being made on Lafayette’s behalf. He lamented Madame de Corny’s economic downfall and expressed surprise at the sharply religious turn in Cosway’s life. And then Jefferson’s love of language took flight:

And Madame Cosway in a convent! I knew that, to much goodness of heart, she joined enthusiasm and religion: but I thought that very enthusiasm would have prevented her from shutting up her adoration of the god of the Universe within the walls of a cloyster; that she would rather have sought the mountain-top. How happy should I be that it were mine that you, she and Mde. de Corny would seek.

Church knew Jefferson well enough to recognize what he was doing writing to her in this manner. Even as he flirted with Cosway, he had flirted with her over the years, fully aware that no connection to either woman (both married, Church with two children) could ever be serious or long-term. His suggestion that Cosway, Church, and Corny might repair to Monticello to live with him was on par with other fanciful things he had said to her before.

At this moment, however, matters were more complicated because in addressing Church, Jefferson was talking to the sister-in-law of the man responsible for his current discomfort: Hamilton was married to Church’s younger sister, Elizabeth. Open discussion of the implications of this fact in the letters they exchanged was not possible, given Jefferson’s sense of propriety and strong dislike of conflict. He could not let on that he even considered that Church knew of the titanic struggle that he and her brother-in-law had waged. Instead, he went back to basics, to a presentation of self that emphasized his attachment to his home, his values, and his faith that, with concerted effort, he could bend the future to his will.

In the mean time I am going to Virginia. I have at length been able to fix that to the beginning of the new year. I am then to be liberated from the hated occupations of politics, and to sink into the bosom of my family, my farm and my books. I have my house to build, my feilds to form, and to watch for the happiness of those who labor for mine. I have one daughter married to a man of science, sense, virtue, and competence; in whom indeed I have nothing more to wish. They live with me. If the other shall be as fortunate in due process of time, I shall imagine myself as blessed as the most blessed of the patriarchs.

The most blessed of the patriarchs. The strong proponent of republican values, adherent of the Enlightenment, who wrote that “all men are created equal” and was excoriated as a “Jacobin” by enemies, likened himself to a figure from ancient times when republicanism was not even thought of, much less the Enlightenment or revolutionary action to upend the social order on behalf of the down trodden. Though the word “patriarch” can be used to describe any man who was the “father” of something—Jefferson did this on occasion, himself— his setting of the scene and description of what he would be doing at Monticello suggests that he meant something more particular than just being a father. Indeed, two years later in a letter to Edward Rutledge, Jefferson more explicitly linked himself to the primordial incarnation of such a figure when he said that at Monticello he was “living like an Antediluvian patriarch among [his] children and grand children, and tilling [his] soil.”' “Antediluvian patriarch[s]” of the highest status— and Jefferson was of high status—ruled over families that included a wife (sometimes multiple ones), concubines, children, and slaves. Depending upon his social position, his authority could extend to a clan or to a surrounding community. A salient feature of his rule was that it was autocratic, a form of leadership at odds with the type that Jefferson championed when he participated in the American Revolution, supported the French Revolution, and worked to build the government in the earliest days of the United States.

In fact, Jefferson had no wife when he wrote to Church in 1793, or when he wrote to Rutledge in 1795, but he did have a concubine, children, slaves, and over five thousand acres of land. And if the members of his surrounding community were not in a truly dependent relationship to him, as those who lived under the aegis of a high-status patriarch of old would have been, they did, in the main, respect him and rely on his capacity to provide things they needed in their lives. Monticello’s blacksmith shops, its nail factories, the mills Jefferson built, the jobs he offered for skilled white workers—his property and prestige—helped shape the way of life in the community around Monticello. Indeed, ninety miles away from the mountain, people who lived in the vicinity of his Bedford County retreat, Poplar Forest, took to calling him “Squire.” Though lacking the more exotic connotations of the word “patriarch,” the title nevertheless acknowledged Jefferson’s special status, reaffirming his sense of himself as one who occupied a privileged place—with attendant responsibilities—in his home and community.

That Jefferson called himself a patriarch provides a window into his thinking about his place in the world and his sense of self. But what kind of patriarch did Jefferson wish to be, or want others to think he was given the roles he played in his country and in the world at large? At the time he wrote to Church as he prepared to go home, he was closely associated in the public mind with a revolution that was in the process of ripping apart the fabric of society with the announced aim of creating something entirely new. Just eleven months earlier, in service of that revolution, and in the name of its newly constituted citizenry, France had executed the country’s patriarch, Louis XVI, an act that left Jefferson unfazed. Even in the face of the chaos in France, the republican revolutionary whose Declaration of Independence deposed America’s monarch was cautiously optimistic about the future of republicanism in France and throughout the “civilized” world.

To his extreme enemies Jefferson was a bloodthirsty Jacobin, someone who would disrupt and obliterate traditional lines of authority within society. This characterization went too far, but Jefferson did in fact see himself as part of a vanguard of a progressivism fueled by Enlightenment thinking that would inexorably strip away the old order to make things anew. What has fascinated (and annoyed) many observers of the man, from his time until well into our own, is that he would dare to launch himself into this role from such an improbable base of operations: a slave plantation. Jefferson was a lifetime participant in an ancient system that made him the master of hundreds of people over whom he had near-absolute power. He could buy and sell human beings. If hostility to tyranny was at the heart of his politics and plan for the United States of America, that sentiment had no real currency on his mountain. At the same time, he well understood the basic problem with his way of life and wrote damning and insightful criticisms of the institution that made it possible. An important part of the story we wish to tell is how this progressive patriarch came to rest easy within the confines of a way of life that he believed to be retrogressive.

As the principal author of what has come to be considered America’s “creed,” the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson is subjected to greater scrutiny than other of his contemporaries—including James Madison, James Monroe, and Patrick Henry—who spoke of liberty as a fundamental right while holding other human beings in bondage, even as they, like Jefferson, claimed to abhor slavery. The distance between Jefferson’s words and his deeds on this question, along with other apparently contradictory impulses—the masterful politician also claimed to hate politics—has led some critics to simply brand him a hypocrite and leave matters at that. This is an understandable, even predictable response. But it is ultimately shallow because it is far too easy on his times, on his fellow white Americans, and on all of us today. There is indeed a much richer, more complicated and important story to tell about the world Jefferson inhabited and the way he moved through that world. Even more fascinating is to consider the way he saw himself moving through a world he had helped bring into being, for which he felt great responsibility, and for which he had nearly boundless hopes. Jefferson’s hopes for the American republic and his firm belief that the United States would create an “empire for liberty” to stand in opposition to the empires of the Old World were products of the empire of his imagination—a place created out of the books he read, the music he played and the songs he sang, the people he loved and admired, his observations of the natural world, his experiences as a revolutionary, his foreign travels, his place at the head of society and government, his religion, and his role as one who enslaved other men and women. From all of this grew a republican patriarch of his own fashioning. It is this process—and its outcome—that we wish to explore.

Jefferson believed that mankind’s condition would get better and better as the years unfolded, with the United States taking the lead role in bringing this process to fruition. The path of science—the product of the human capacity to reason—was his template for the future course of human events. As education became more widely diffused, technology and science would advance, retrograde superstitions would fall by the wayside, and republican forms of government resting on the consent of “the people” would eventually cover the earth. The end result of progress would be a state of peace and comity between nations. It is safe to say that modern sensibilities more often than not reject the notion of a future of inevitably rising fortunes for Homo sapiens. Indeed, the most pessimistic among us wonder how long—or whether—the species will last at all. Current-day observers are likely, then, to see Jefferson as naïve or, at best, disingenuous—he cannot really have believed those things he said about progress and inevitable improvement. Again, the chasm between words and deeds fuels skepticism. But despite mounting evidence in his own lifetime that there would be no straight line to the bright future he envisioned, Jefferson sustained his Enlightenment faith in human progress until his dying days.

Ironically, the historian who helped craft the persistent image of Jeffersonian slipperiness-shading-into-inscrutability also gave evidence to the contrary. In 1889 Henry Adams very famously set the tone for writing about Jefferson in his magisterial History of the United States of America with the following often quoted passage:

The contradictions in Jefferson’s character have always rendered it a fascinating study. Excepting his rival Alexander Hamilton, no American has been the object of estimates so widely differing and so difficult to reconcile. Almost every other American statesman might be described in a parenthesis. A few broad strokes of the brush would paint the portraits of all the early Presidents with this exception, and a few more strokes would answer for any member of many cabinets; but Jefferson could be painted only touch by touch, with a fine pencil, and the perfection of the likeness depended upon the shifting and uncertain flicker of its semi-transparent shadows.

A seductive and poetic image to be sure, but “shifting” also suggests shiftiness—a subtle indictment of Jefferson’s character from a man whose ancestors John and John Quincy Adams had at best ambivalent relations with America’s third president. Henry Adams was a masterful stylist, and there is no wonder that this brief sketch of the supposedly elusive Jefferson has had such staying power in American historiography. Literary and evocative as it may be, however, it is not entirely correct; or one should say it leaves much out of the picture of Jefferson’s life—and of the lives and characters of the other early presidents, who were as complicated as most human beings tend to be, a reality that Adams’s formulation breezes right past. We invoke other literary figures—actual poets—to comment on the reality of Jefferson’s (and humankind’s) constitutively multifaced nature. The Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, himself a figure of enigmatic repute, put it this way: “Each of us is several, is many, is a profusion of selves. So that the self who disdains his surroundings is not the same as the self who suffers or takes joy in them. In the vast colony of our being there are many species of people who think and feel in different ways.” Pessoa, who wrote poetry in dozens of different voices and personalities, was speaking of the human condition in the early twentieth century, but Jefferson was ahead of his time in many ways and had a personality that would neatly fit within Pessoa’s description. And then there is Walt Whitman, whose more famous lines are especially appropriate for Jefferson because they so well capture the restless, ever transforming spirit of American democracy—“Do I contradict myself? Very well, then. . . . I contradict myself; I am large. . . . I contain multitudes.”

Pronouncing Jefferson a particularly contradictory figure whose shifts and “uncertain flickers” make him harder to capture than other presidents, or other people, also fails to take into account the numerous and varied roles that he played during his very long life, and what playing those many roles demanded of his personality, in ways good and bad. He served at nearly every level of government that existed in pre- and post-revolutionary America, and retired to found a university. While he was accomplishing these feats, he also maintained a set of personal interests and occupations that were extremely varied as well, enough to sustain a veritable industry of “Jefferson and” books and articles—“Jefferson and slavery,” “Jefferson and architecture,” music, wine, cooking, horticulture, religion, linguistics, paleontology. What can we make of a man who was so many things over such a long period of time?

As it turns out, another of Adams’s observations about Jefferson is more on the mark than his intimations of his subject’s inherent shadiness. He emphasized Jefferson’s capacity for steadfastness of purpose (or outright stubbornness) about cherished principles, even in the face of the disastrous practical consequences that adherence to those principles wrought: “Through difficulties, trials, and temptations of every kind he held fast to this idea, which was the clew to whatever seemed inconsistent, feeble, or deceptive in his administration.” Adams was speaking of Jefferson’s attitude about peace, noting that in his desire to avoid war, at what looked to be all costs, Jefferson was willing to appear “inconsistent” to the point of seeming “untruthful.” “He was pliant and yielding in manner, but steady as the magnet itself in aim.”

With this, Adams deftly distinguishes strategy from tactics, and tells a truth about Jefferson that should be applied to other areas of his life. Whether he was acting as a politician, a father, a master of a slave plantation, or in any other important role, Jefferson almost always had an overall goal (or strategy) in view that can be obscured by the tactics he employed. This was certainly true with respect to roles that were even more central to his life than the pursuit of peace. The revolutionary patriot was willing to do whatever he thought necessary to ensure the bright future he saw for the country he helped found.

Throughout the arc of his long career, Jefferson saw himself and like-minded patriots as being in a never-ending battle to sustain the “Spirit of ’76” against the British and “aristocratic” and “monocratic” Americans who sought to make the United States like Great Britain and, thus, roll back the gains of the revolution. Rejecting the Old Testament pronouncement “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again, there is nothing new under the sun,” the just inaugurated President Jefferson emphatically declared in March of 1801 when speaking of the nascent American republic, “We can no longer say there is nothing new under the sun.” He wrote this in a letter to the eminent scientist Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen, describing what he thought had been at stake in the bitter struggle that had led to his election.

The barbarians really flattered themselves they should be able to bring back the times of Vandalism, when ignorance put everything into the hands of power & priestcraft. All advances in science were proscribed as innovations. They pretended to praise and encourage education, but it was to be the education of our ancestors. We were to look backwards, not forwards, for improvement; the President himself declaring, in one of his answers to addresses, that we were never to expect to go beyond them in real science.

The forces of good had triumphed over the forces of evil. Jefferson, in full patriarchic mode, was absolutely sure he was right about this.

And much as he admired George Washington, it seems clear that, deep down, Thomas Jefferson viewed himself as the real father of this country. He wrote as if the United States had become its true self only in the 1790s when the Democratic-Republicans, a group that favored the inclusion of the common man in the governance of American society, challenged the prevailing order that the Federalist Party had put in place. These artisans, small farmers, and working people looked to Jefferson for leadership. They went on to become members of what would be called the Democratic-Republican Party, and propel him to the presidency in 1800. With that powerful role came the responsibility to act when necessary. Jefferson’s sincere, heartfelt dedication to the fundamental principles that he believed defined the new republican regime justified tactics that skeptical critics—equally convinced of their own patriotism and probity—might rightfully have found questionable.

Jefferson, the republican patriarch: How did he come to think of himself in this role, and how did he conduct himself in it? In what ways did this particular self-construction—this Whitmanesque “large” sense of himself—influence the way he moved through the world as a plantation master, father, grandfather, revolutionary, public official, and, finally, elder statesman? How did he deploy the tremendous resources at his disposal—his talent, ambition, wealth, personal will, and social position—to fulfill the roles he set for himself early on in life? What did Thomas Jefferson think he was doing in the world?

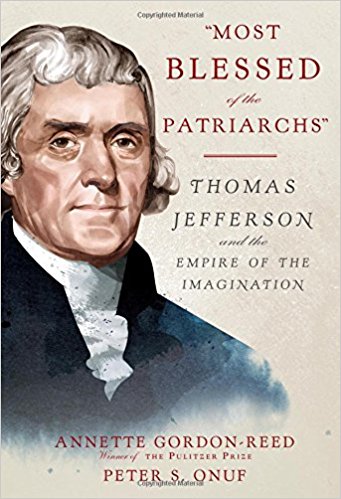

These are the questions we will explore and hope to answer in “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs.” Our goal is not to critically assess how Jefferson made his way through the world and determine what his life might or should mean for us, for better or for worse—what we think he ought to have been doing. We instead seek to understand what Thomas Jefferson thought he was doing in the world. Toward this end we do something that we think is absolutely essential: whenever it is at all reasonable to do so, we take Jefferson at his word about his beliefs, goals, and motivations. Readers should be clear: this does not mean that we always endorse Jefferson’s formulations of why he did things or what he thought about matters, or that we are not mindful of the very problematic nature of some of his actions and thoughts, and their consequences. With this in mind, we look at the many and varied aspects of his life to try to present a picture of the total man. Jefferson’s attitude about slavery, race, and the role of women are as much a part of this story as his actions as a politician, his ideas about government, and his vision of the new nation’s future.

It must be said that designating some of Jefferson’s positions as “problematic” is not merely a function of failing to recognize that he lived in another time. On some issues of great moment to present-day observers—particularly race and gender—he was at odds with at least a few of his more enlightened contemporaries. It was certainly possible for him to have risen above conventional attitudes on such questions. Yet if one is determined to keep score, it should be said that Jefferson was far ahead of his time on other extremely important matters. He was willing to question religious dogma, argue for the separation of church and state, and welcome scientific insights and advances with an open mind. And, as Henry Adams noted, he saw peace as the ultimate goal of statecraft. The quest for dominion and glory through war had wreaked needless destruction and caused “rivers of blood” to flow throughout human history. In Jefferson’s view, “Nature’s God” clearly had a loftier design for his “Creation,” one that was beginning to become intelligible to enlightened people.

WE TURN To Adams again, writing in another context, to comment further on Jefferson’s progress through life. An observation that Adams made about those born at the turn of the twentieth century could fit very well with Jefferson’s experiences, though he was a man of the eighteenth century. Pessoa wrote about the fracturing of the modern personality brought on by modern times. Adams wrote of the fractured times themselves. “The child born in 1900 would, then, be born into a new world which would not be a unity but a multiple,” a circumstance he lamented in his masterpiece, The Education of Henry Adams. This new world grew out of some of the ideals that Jefferson championed, and those that were attributed to him. The worth of the common man, the professed belief in equality as a value in society, skepticism toward old orders, especially organized religion, and faith in science and technology all fired Jefferson’s imagination. He had been born in one world, and helped to make a new, more expansive one. His questing and idealistic nature made him determined to use his own life as a model for doing the many and varied things that were now possible in the world that had been born in 1776—and people knew that about him; some loved it, others hated it. The likely apocryphal story that he ate a tomato in front of a courthouse in order to prove that tomatoes were not poisonous, as many Americans believed in the eighteenth century, is just one example of how deeply Jefferson’s image as a harbinger of the new took hold in the public consciousness over the course of his career. It has remained there to this day, as Jefferson is cited as having brought to America everything from ice cream to scientific racism.

SO MUCH HAS been written about this republican patriarch, a near-countless number of articles, essays, and books—both nonfiction and fiction. Many stated “truths” about Jefferson are too often merely endlessly repeated opinions—and more or less explicit judgments— about the meaning of his words and deeds. This is not to suggest that many of these opinions have not been useful or correct. It is to say that we are in a particularly critical and, potentially, transformative time in Jefferson scholarship. We now have so much more available information about him that a reassessment of him based on what we now “know” is very much in order. Since the 1990s there has been an explosion of new information about slavery at Monticello, revolutionizing our understanding of his role as master of that plantation and of his home away from home, Poplar Forest. The task of editing The Papers of Thomas Jefferson has sped up enormously— the project having been split in two with Barbara Oberg at Princeton University editing the years before his retirement in 1809, and J. Jefferson Looney at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (Monticello) editing The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series. Thanks to their herculean efforts, volumes have been appearing yearly, complete with the most reliable transcriptions of his letters and writings, supplemented by deft editorial notes that provide illuminating details about the people and matters contained in the correspondence. A side project of the Retirement Series, The Family Letters, presents correspondence of members of Jefferson’s family—Jeffersons, Randolphs, Hemingses, Carrs—up until the Civil War years. In it family members provide us with heretofore unknown information about things that happened in Jefferson’s life as far back as the 1780s, and clarify the facts surrounding familiar events.

More than anything else, these letters show the value of using others’ observations of Jefferson to ferret out how they perceived him and, more importantly for our purposes, how he wished to be perceived. Finally, it is impossible to overstate the value of the publication in 1998 of Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, edited and annotated by James A. Bear and Lucia (Cinder) Stanton. Jefferson’s record of his daily life, with notes that explain his references and flesh out context, is perhaps the single greatest contribution to Jefferson scholarship since the publication of his letters began. There is much new material to work with here.

The most familiar narrative of Jefferson’s life and the generally accepted understanding of his character were put in place many years ago. Henry Randall’s nineteenth-century biography created the arc of the story, though Dumas Malone, writing from the 1940s to the 1980s, certainly improved upon Randall in many ways and refined the presentation. But even without new information, every generation of historians asks different questions about the material that is available to them. They, and their readers, have a set of cultural expectations that form the basis of their engagement with historical persons and events. For example, Randall and Malone came of age in and wrote during a time when the racial views of the dominant culture precluded seeing enslaved blacks, and Jefferson’s attitudes about them, as having any great relevance to shaping Jefferson’s life or determining how we should view him. Because they were neither inclined nor equipped to ask questions about the role of gender in Jefferson’s life and times, they did not delve deeply into his relations with his wife and daughters and their families. Impressed and inspired by Jefferson’s central role in the nation’s founding, both writers tended toward a hagiographic approach to their subject, although Malone became less so over the course of completing his six-volume work on Jefferson.

There has been a reaction to these earlier portraits of Jefferson, and the pendulum appears to have swung all the way in the opposite direction. “Jefferson the God” has given way to “Jefferson the Devil.” We hope to steer clear of both of these presentations, making use of the plethora of new information that broadens our understanding of Jefferson, even as we reassess the material that has been known in light of contemporary understandings of politics, race, and gender. With that said, “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs” is hardly meant to be a conventional biography of Jefferson that runs chronologically from his birth to his death. Instead, the chapters in each of the book’s three parts tell his story through our discussion of the most salient aspects of Jefferson’s philosophy of life—how it was developed, how it evolved, and how his thoughts and feelings shaped his actions and the course of American history. In Part One (“Patriarch”), “Home,” “Plantation,” and “Virginia” present the influences that went into shaping Jefferson’s life and continued to give meaning to his existence throughout the eighty-three years that he lived. The chapters in Part Two (“ ‘Traveller’ ”)—“France,” “Looking Homeward,” and “Politics”—present Jefferson at work in the world on the business of the newly formed United States as a diplomat and public official, and show how these experiences further molded him into the figure most recognizable to the public during his lifetime and to readers of history, while Part Three (“Enthusiast”) contains the final three chapters: “Music,” “Visitors,” and “Privacy and Prayers.” These chapters explore some of the things beyond politics and work that were at the core of Jefferson’s identity, helping to shape his relationships with others, and sparking his reflections on the meaning of his life as it was about to come to a close.

Rather than write a conventional biography, we looked at the most salient aspects of Jefferson’s philosophy of life—how it was developed, how it evolved, and how his thoughts and feelings shaped his actions and the course of American history

We are often asked, “What is left to be known and said about Thomas Jefferson?” The answer, we think, is “Everything.” There is little doubt that he was the central figure in the early American republic. No one’s contribution to and participation in the formation of the American Union was of longer duration and more sustained influence. This book is designed to be neither a running critique of Jefferson’s failures nor a triumphant catalog of his successes. It attempts, instead, to explicate the life of an endlessly fascinating figure of American history who had his hand in so many disparate parts of the nation’s beginnings that it is impossible to understand eighteenth-and nineteenth-century America—and the country the United States has become—without grappling with him and his legacy.

Copyright © 2016 by Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf