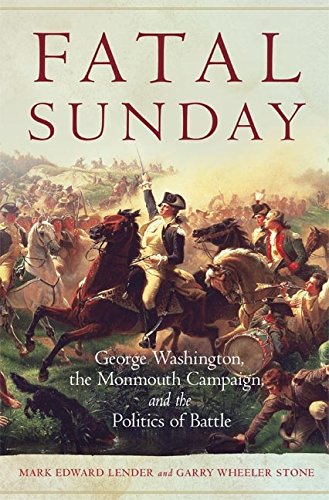

The battle of Monmouth was pivotal in the struggle for independence, enabling George Washington to change the narrative of the war and eventually solidify his own role in our nation's history.

-

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2017

Volume62Issue4

Unlike Saratoga or Yorktown, the battle of Monmouth was not a clear-cut American victory. After a long, difficult day of fighting, the British surprised the rebels by abandoning their positions before the following dawn, and later claimed victory because their orders had been to march from Philadelphia to New York with their army and supplies intact, which they did. The authors of Fatal Sunday make a persuasive argument, however, that Monmouth was critical to the success of the Revolution and a decisive turning point in the career of George Washington.

--the Editors

The Battle of Monmouth was fought on Sunday, 28 June 1778. The bulk of the action took place just outside the village of Monmouth Court House (modern Freehold), New Jersey, the seat of Monmouth County. It was one of the largest battles in the War for American Independence, was the longest single day of combat, and marked the effective end of British efforts to achieve a military victory in the northern colonies.

The battle was part of a three-week campaign in mid-June and early July—the time it took the British to evacuate Philadelphia, march across central New Jersey, and reach safety in New York City. It pitted the rival commanders in chief, the American George Washington and the Briton Sir Henry Clinton, directly against one another; it was the only time they met in the open field. Monmouth saw some

particularly dramatic and bitter fighting, and it was the root of subsequent military and political controversies that reverberated through the army, in the Continental Congress, and across the rebellious colonies. It was a battle that gripped the public imagination, with many Americans initially believing it heralded an early end to the conflict. But even after these hopes had faded, and long after the guns had fallen silent, aspects of the Battle of Monmouth remained matters of contention. Some stories would echo into American folklore.

For patriots, Monmouth had immediate significance. At day-break on Monday, 29 June, exhausted rebel soldiers, who had slept on their arms expecting a resumption of the fighting, discovered that the battle was over. The British were gone, having moved out during the night; the astonished Continentals and their militia compatriots held the field. It was the first time in over a year that troops under General Washington could make such a claim. Elated, they made the most of the result. “It is Glorious for America,” Colonel Israel Shreve, commanding the Second New Jersey Regiment, wrote his wife, Polly. “The Enemy was Drove off the Ground,” he exulted, “and many British Grenadiers and Light Infantry lay weltering in their gore.” Shreve’s excitement was typical, Colonel William Irvine was equally overjoyed. “The Americans never [held] the field” before, he wrote a friend, but they did this time and trounced “the pride of the British Tyrant” in the bargain.

Beyond such satisfaction, the rejoicing had an element of sweet revenge. One soldier wrote home that the enemy dead were the same men who had beaten the Continentals the year before at Brandywine and elsewhere, making the results now all the more glorious. Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, in the thick of the fighting at Monmouth, was especially satisfied. He relished a none-too-subtle jab at certain young women of Philadelphia—those who had courted the attentions of occupying redcoat officers. Wayne asked a friend in the city to “tell the Phila. Ladies” their former beaus had “humbled themselves on the Plains of Monmouth.”‘ Among rebel officers, desperate to even the score with the British after long months of frustration, the story was the same: The Continentals had met the flower of the King’s army in a fair fight and had brought it low.

Yet the British saw the Monmouth affair in strikingly different terms. Lieutenant General Clinton winked at American boasts. Washington could claim victory all he liked, but in reality, Clinton coolly observed, “Nothing, surely, can be more ridiculous.” He had orders to get his army back to New York, which he had successfully executed. During the march from Philadelphia, he not only had brought his army through the heart of enemy territory but also had done so in the face of superior numbers without the loss of even a single wagon. He believed he had done well enough; his only real disappointment lay in the fact that Washington never gave him a chance for a general action.

Sharing their commander’s assessment of events, some of Clinton’s subordinates used hyperbole as expertly as the Americans ever did. Hessian captain Johann Ewald, whose jaegers were in almost constant action during the march, considered the campaign a marvel. “The retreat of Xenophon and his Ten Thousand Greeks,” he wrote, “could not have had more hardships on their marches than we endured,” and yet the army reached safety. Officially at least, the British were well pleased with their performance.

In assessing the outcome at Monmouth, some able historians, early and modern, have split the difference between British and American accounts. In her 1805 history of the Revolution, Mercy Otis Warren, hardly likely to flatter the British, took exactly this perspective: “After the battle of Monmouth,” she wrote, “both parties boasted their advantages, as is usual after an indecisive action.”‘ There is a certain logic to this middle ground. On the American side, it is possible to discount inflated victory claims and still credit a gritty battlefield performance. The rebel army that fought on 28 June was a force to reckon with, and there is a great deal to be said for seeing the battle as the Continental Army’s “coming of age.” On the other hand, Clinton would have evacuated New Jersey regardless of anything Washington had done; if the British commander had refused to reengage after Monmouth, he had done so fairly certain that Washington was not about to offer a showdown fight. Under the circumstances, Clinton acted professionally and got his army to New York for redeployment.

So there it is: a hard-fought battle with no clear decision in the field, one in which both sides took some satisfaction, and one that seemingly did not alter the fortunes of war. From a purely tactical perspective, it would be hard to argue with the conclusion of historian Willard Wallace: “if ever a battle was a drawn struggle, Monmouth was it.”

This tactical perspective, however, may be too limited, for it may have obscured an appreciation of the strategic intentions of the commanders, the significance of the engagement, and especially its aftermath. The Monmouth campaign occurred during a particularly interesting and fluid period during the Revolution. The context of the war was changing. In late 1777 the British had lost an entire army at Saratoga, and by early 1778 the French alliance and the rejuvenation of the Continental Army during the Valley Forge winter promised to alter the strategic balance. British military plans, including redeployments that had led directly to the evacuation of Philadelphia and the action at Monmouth, raised additional questions about future operations. Certainly patriot political and military prospects appeared to be brightening, but the future was anything but clear.

Thus, as the British planned their move across New Jersey and as General Washington and his subordinates pondered their response, they did so amid open questions about the future conduct of the war, including its new international dimensions. There also were questions about the capabilities of patriot arms and, perhaps most significantly, the abilities of Washington himself. Indeed, as the Monmouth campaign opened, the general was something of an unknown quantity. Despite his flashes of brilliance at Trenton and Princeton and the regard many patriots had for his character and dedication, his performance as commander in chief was questionable.

Some contemporaries could not forget the painful defeats around New York in 1776 or the bitter loss of Philadelphia in 1777. This was no record to support a reputation in arms, and as early as late 1776 there were doubts about Washington’s fitness to command. Among others, Adjutant General Joseph Reed and, most notably, Major General Charles Lee, the army’s second-ranking officer, groused indiscreetly (but reasonably) at Washington’s performance. Worse came the following year: The defeats around Philadelphia stood in bold relief against Major General Horatio Gates’s victory at Saratoga, triggering unflattering (for Washington) comparisons between the two patriot commanders.

That Washington’s generalship had drawn censure was no surprise. Historically, it was (and has been) no rare thing to sack losing generals: consider the generals Abraham Lincoln relieved before finding U. S. Grant, or the commanders tossed out of their jobs (and lucky to keep their heads) by the government of revolutionary France. After Major General Arthur St. Clair’s 1777 retreat from Fort Ticonderoga, even John Adams mused about shooting underachieving commanders.

Viewed in this light, the Revolution presented something of an exception since the patriot commander in chief actually kept his job. But the criticisms of 1777 were serious, and at least some disaffected leaders in the army and civil circles, including Congress, toyed with trading Washington for Gates. Their plans, such as they may have been, had jelled loosely in the so-called Conway Cabal. Fortunately for Washington, his critics were better at talk than action, and they fell into embarrassed silence when their slights became known. He had weathered the storm, but he and many of his military and civilian allies believed there had been a serious plot to replace him.” Nevertheless, however inchoate or even foolish the general’s critics may have been, the fact is that he had serious doubters in and out of the army, and there were legitimate questions about his record.

Beyond Washington’s performance on the battlefield, however, lay broader questions about the capabilities and future of the army itself. Throughout the months at Valley Forge, and especially in early 1778, the general had worked feverishly at improving supply and training and on the myriad tasks inherent in reinforcing, reequipping, and reorganizing the depleted Continental regiments. Success in these areas would factor heavily in the army’s future performance, and securing the necessary resources taxed Washington’s administrative and political skills to the utmost. Often frustrated, he dealt tactfully with civilian authorities, most of whom understood the necessity of military reform but often quibbled over details. Some even questioned why patriot forces delayed offensive action, their desire to avenge the loss of Philadelphia blinding them to the disabling realities still confronting the recovering patriot regulars. At Valley Forge, nothing came easily.

There was even a challenge to Washington’s vision for the army’s future. He was adamant in his belief that only a professionally trained, regular Continental Army could stand up to the British in the field; this, he insisted, was the key to ultimate victory. But not everyone agreed, including some members of Congress and others active in political circles. In particular, General Lee refused to believe American regulars could ever beat redcoats at their own game. Trained on a “European Plan,” Lee warned, American troops would “make an Aukward Figure, be laugh’d at as a bad Army by their enemy, and defeated in every Renecontre which depends on Manoevres.” But most officers agreed with the commander in chief and loyally supported his efforts to reorganize and retrain the army, although there is little doubt criticisms of their chief, from whatever quarter and for whatever reason, left many of them smarting.

Thus on 18 June 1778, when the first Continental units broke camp at Valley Forge to shadow Clinton into New Jersey, Washington fully understood that a great deal rested on his performance and that of his army. But while the general was still in command, he was not above criticism. And though it was clear that the army that marched out of Valley Forge was better than the one that had straggled into that encampment following the disappointments of 1777, it was not clear how much better. Perhaps the only thing that was clear was that the pursuit of the British would test both the rebel general and his remodeled battalions. An additional major defeat, or even a lackluster campaign, could well have triggered another and more concerted challenge to his leadership; he and officers loyal to him must have understood this. There is no question the general wanted at least some modest success in 1778 to compensate for his poor showing the previous year. For Washington, the stakes of the new campaign would be as much political as military.

Washington got rather more than a modest success. The patriot commander in chief emerged from the Monmouth campaign with his critics cowed into silence; his potential rivals in the officer corps routed or, in the case of General Lee, actually disgraced; and his military reputation praised in terms fit for an Alexander or a Caesar.

In fact, the aftermath of Monmouth saw Washington with his prestige so enhanced that, for the rest of the war, he was beyond any real censure, much less any challenge to his command. It is not too much to say that the campaign confirmed the patriot commander in his status as the proverbial “man on the white horse,” or in James Flexner’s parlance, the “indispensable man.”‘ This was a dramatic reversal of fortune in any event, but it was all the more remarkable in that it derived from what some careful studies have insisted was a drawn battle.

Was this really possible? Victories usually make military reputations and keep generals in their jobs, not tactical standoffs. This observation alone is enough to raise questions about what actually happened near Freehold on 28 June. Have we profoundly misunderstood some critical aspects of the battle? Were the results of the fighting more far reaching than previous scholarship would have us believe? A reassessment of events immediately after Monmouth suggests this was indeed the case, and these same developments held the key to Washington’s ability finally to consolidate his hold on the army. Indeed, the Monmouth campaign was the hinge upon which the fate of his command turned, the point at which the general was able to put to rest questions about his competence and silence his critics once and for all. Monmouth was the key to why Washington kept his job, and thus its significance looms considerably greater than a hard-fought draw.

How this turn of events came about involved more than the results of combat. Much depended on the steps Washington and his lieutenants took to burnish his reputation in the aftermath of the battle—in effect, to convince patriots that Monmouth had been a major triumph, no matter what the tactical realities may have been, and to use this perception to enhance Washington’s stature. None of this is to imply that the general and his army had not fought well at Monmouth—far from it. But the politics of battle—the skirmishes in Congress and the campaign for public opinion that both preceded and followed the engagement—were for General George Washington every bit as important as the battle itself.

Because the politics and the realities of that Fatal Sunday are so interwoven, an understanding of military operations, including the details of the fighting on 28 June, is central. Such an understanding, however, is more readily proposed than realized. Some fifty years ago, in an essay on Charles Lee, historian John Shy observed, “there is no satisfactory account of the Monmouth campaign.” His comment remains accurate. Any number of authors have tried to make sense of the fighting, and their efforts have suffered from no dearth of evidence. In fact, the problem has been quite the reverse. The Monmouth campaign involved thousands of patriot and British troops, and it took place in a relatively populated region. Thus plenty of eyewitnesses had more than enough time to see or experience at least some aspect of events, and they produced a plethora of contemporary accounts. But as is the case with most history, these accounts were refracted through the proverbial fog of war, personal and political biases, honest mistakes, and the eyes of those who simply did not understand what they saw.

Also contributing to the confusion were elements of Continental and international political developments, bitterly clashing personalities, evolving British and American tactical considerations, changing conditions within the patriot and royal armies, geography, and as events transpired, even the weather. Of course, much the same can be said of most military operations, but at Monmouth the impact of all these factors seemed especially pronounced. No wonder historians generally have considered Monmouth to be one of the most difficult of all engagements of the Revolution to understand. “It remains to this day the hardest battle of the war to chronicle,” wrote Robert Bray and Paul Bushnell, “let alone to analyze.”

Our effort to come to a better understanding of the battle and its consequences was helped by access to a remarkable trove of new research material, many unavailable to previous studies. These include American and British manuscripts and other original sources as well as a wide range of newer scholarship on specific aspects of the Monmouth campaign. We have drawn heavily on British and translated Hessian sources in an effort to clarify the royal army’s movements and the thinking of its commanders and soldiers. The results of battlefield archaeology, a wealth of pension applications, and new cartography have assisted greatly in deciphering the course of the fighting and in correcting many misconceptions about how the rival forces maneuvered as they did. More recent studies, including valuable unpublished research, provide often-graphic detail on individual units, while the use of pension records and private correspondence add an important dimension to our appreciation of the personal experience of combat in the eighteenth century. The publication of important documentary editions, notably Letters of Delegates to Congress and the Papers of George Washington (Revolutionary War Series), has offered rich insights into a range of patriot opinions on and reactions to the campaign and its implications.

What emerges is the clearest tactical and strategic view we have of what happened at Monmouth. While events there were complicated indeed, they nevertheless were explicable. Beyond the battlefield narrative, this study also explains how the Monmouth campaign became one of the pivotal events in George Washington’s career as commander in chief. Inasmuch as Washington’s fate was intertwined with that of the Revolution, the Battle of Monmouth must be recognized as a pivotal moment in the success of the struggle for independence itself.