In the bitter debate over the War of 1812, the decorated veteran nearly died fighting a Baltimore mob in defense of an unpopular Federalist publisher.

-

Summer 2019

Volume64Issue3

In the winter of 1778, fewer than a dozen American soldiers, entrenched in a Pennsylvania farmhouse, repulsed a British force of over 100. The skirmish, known as Scott’s Farm, was tactically insignificant. But the daring do of the rebels and their leader provided a jolt of adrenaline to the army languishing at Valley Forge.

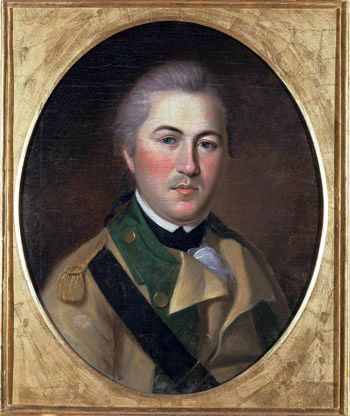

Their leader was Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee III, a young captain of Virginia dragoons who had defeated a Hessian regiment at the Battle of Edgar's Lane and who later won a gold medal from Congress for his actions during the Battle of Paulus Hook.

Three decades later, Harry Lee was called on to defend another home under siege and protect the rights of free expression that had been won in the Revolution. But this time the results would be quite different.

The summer of 1812 brought a cloud of bitter partisanship that would make today’s squabbles seem quaint by comparison. President James Madison’s decision to declare war with Great Britain in June, egged on by Congressional hawks, sharply divided the nation along geographical and partisan lines. The remnants of Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist party, predominately isolated in New England, deeply opposed the war up to the point of eventually considering secession. Meanwhile, Democratic-Republicans, the now ascendant political coalition formed around Thomas Jefferson, heartily supported a second fight with Britain.

The city of Baltimore was a hub of Democratic-Republicans, who controlled its government and police force. This, however, did not prevent Alexander Conte Hanson from exercising his constitutional rights.

Hanson was of patriotic stock. Originally from Montgomery County, the grandson of a president of the Continental Congress and the son of a former chancellor of Maryland, Hanson had established a broadsheet in Baltimore, the Federalist Republic. Exceptionally pugnacious, he filled it with virulent anti-Republican insults.

The publication had merged with another newspaper, the North American and Mercantile and Daily Advertiser in 1809, and set up shop in the wooden home of Hanson’s partner, Jacob Wagner, on the corner of Second and Gay Streets in Baltimore. From there it blasted venomous denunciations of Republican politics and politicians. As a consequence, Hanson was challenged to duels and subjected to lawsuits. Even the city’s few Federalists grew weary of his constant provocations.

On June 20, 1812, days after Congress’s declaration of war with Great Britain, Hanson uncorked a particularly wild manifesto assaulting “the patrons and contrivers of this highly impolitic and destructive war.” It boasted, “We are avowedly hostile to the presidency of James Madison” and promised to “hazard everything most dear, to frustrate anything leading to the prostration of civil rights, and the establishment of a system of terror” that was sure to flow from “the measure now proclaimed.”

Such statements did not sit well with the people of Baltimore. Two days later an angry crowd congregated under the moon before the offices of the Federal Republic armed with axes and hooks. They proceeded to smash their way into the house, tossed Hanson’s printing presses, types, and paper into the street and destroyed them, then tore down the house they had been taken from. The city’s mayor, Edward Johnson, did little to interfere with the horde, but Hanson and Wagner managed to scamper off to safety.

The Federal Republican was not the only target of such violence in Baltimore. Angry Democratic-Republicans had destroyed vessels alleged to have engaged in commerce with Britain and demolished the dwelling of a free black man named James Briscoe for reportedly declaring his affection for that loathed nation and its people. A church housing a black congregation was also in the crosshairs before the city assigned a horse patrol to protect the building.

Hanson temporarily retreated to the town of Georgetown, near the national capital, and resumed production of the paper, mailing editions to Baltimore. These, though, were captured at the post office and destroyed. “We shall cling to the rights of freemen, both in act and opinion, till we sink with the liberties of our country, or sink alone,” he had declared. And indeed in July, spoiling for a fight, Hanson ended his exile.

Sneaking back into Baltimore, he set up shop in a two-story brick dwelling at 45 Charles Street. From there the Federal Republic resumed its defiance On July 27, the day that the newspaper, as he put it, “ascend[ed] from the tomb,” Hanson took aim at Baltimore’s mayor and police for permitting the earlier attack, exposing the paper and its property to the “fangs of a remorseless rabble.” This edition of the paper had actually been printed in Georgetown, but it was distributed in Baltimore; zealously exercising his Constitutional rights, Hanson was begging for a return engagement with the rabble. And he got exactly that.

Many of Baltimore’s Federalists, who had armed themselves after the original round of riots, viewed Hanson’s risky behavior as madness. Accordingly, when Hanson settled into the house on Charles Street he had to find friends from elsewhere to man his new headquarters.

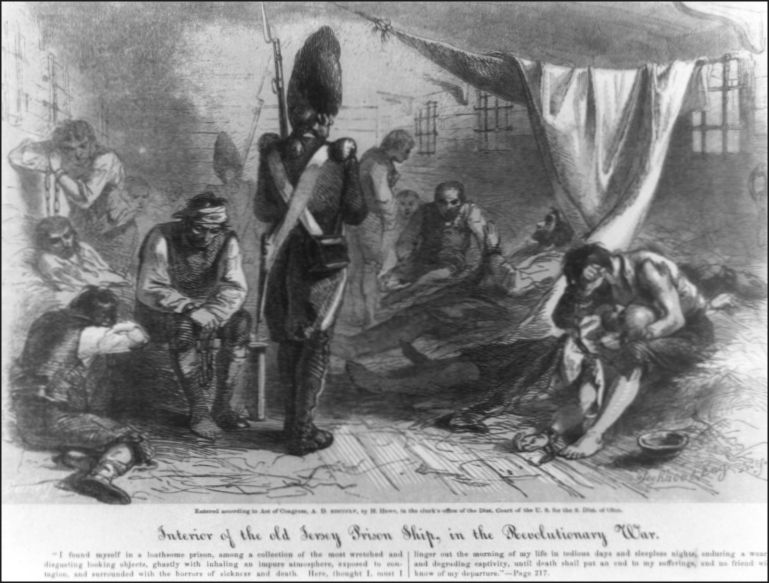

Chief among them was James M. Lingan, a grizzled veteran who had been bayonetted and imprisoned on the notorious British prison ship, HMS Jersey, during the Revolution. He was later appointed the collector of the port of Georgetown and commissioned a general. When Hanson had retreated to that town, Lingan gave him shelter. Lingan was a fierce Federalist and an equally staunch champion of a free press. The supporting cast were younger men: Captain Richard I. Crabb, John Howard Payne, Charles J. Kilgour, Otho Sprig, Ephraim Gaither, John Thompson, Dr. Peregrine Warfield. Major Musgrove, Henry C. Gaither, and William Gaither.

One more man joined the party on Charles Street, serving as its informal commander in chief.

Later he would explain that this was merely a business trip to Baltimore, that he had visited the city on matters relating to his memoirs and called at the house on Charles Street on the evening of the twenty-seventh to visit old friends and play a game of whist.

But as Hanson assembled a small army to defend his business, he recalled the mythology of the American Revolution. In the dire winter of 1778 a young rebel captain, aided by only a handful of soldiers, had repelled a larger British force from a house in the Pennsylvania countryside. Hanson wanted the hero of that episode to come to his defense. He had invited him for that purpose. Never mind that nearly forty years had passed since that fabled morning or that the young revolutionary was now aged and ailing, his youthful lust for battle dissipated.

Every indication suggests that Lee went to Baltimore on a military mission, and that he passed over Hanson’s threshold determined to defend the house and the freedoms he had fought to win another war ago.

On July 20, he sent an unsigned letter to Hanson, outlining how the house on Charles Street could be defended. He wanted two men posted at each window and the stairway just beyond the front door barricaded. A stockpile of stones and logs on the home’s upper level should be ready to be dropped on invaders.

“Should the iniquity of the mob render it proper for you to implement my advice,” Lee cautioned, “remember that you ought not to provoke their action, that you ought to require in time the aid of the civil authority, and that you having begun defense, must never ever think of concession—Die or conquer.”

Sixty men, at a minimum, were necessary to defend the home. And they were to approach their mission with military regimentation. Roll call was scheduled for 6:00 pm, after which no man was permitted to leave. Lee even wanted a spy ring, with men leaving the house during the day to gain intelligence on the plans and movements of the enemy.

As the sun receded and the sky darkened on the evening of the twenty-seventh, a crowd began to gather around the house on Charles Street. It consisted of young men, laborers, and sailors, many of them immigrants, all Democratic-Republicans. Shortly before 8:00 p.m. a carriage pulled to a halt before them. From it muskets were hurried into the house, only piquing the pique of those gathered outside.

Some of the crowd milling about scooped up stones and chucked them at the house. Soon windowpanes were shattered, sashes and shutters smashed, a member of Hanson’s party, Harry Nelson, injured. Now Hanson showed himself at an upstairs window and addressed the mob. If they would not leave, he explained, they would be repelled by gunfire; blank shots were fired overhead to prove the point. But this only further angered the already angry men below.

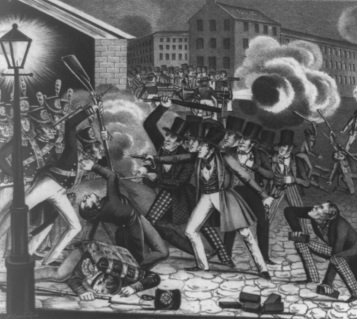

There was a rush to bash in the front door, accompanied by screams of “Death!”

Lee had stressed that every measure should be taken to avoid the spillage of blood; a plea for protection should be made to the city’s authorities.

But now he was thrown into a defensive crouch. He sent a sentry to the stairs facing the now smashed front door; in its place, chairs and tables formed a makeshift barricade. A stalemate lasted for two hours; then at 11:00 the mob, led by an electrician, Dr. Thaddeus Gale, worked up the will to finally push forward into the building. “I will lead you on, and we will kill every dammed rascal in the house!!” he shouted. But as they entered the home, a hail of fire greeted them. Gale was killed, others injured. The mob retreated, firing shots of their own, wounding one of Lee’s party, Ephraim Gaither. Men of the attacking mob tore open their shirts, beat their chests, and screamed, “Fire again!”

There had been no sign of any representative from the city or its police force until at 10:00 p.m. Judge John Scott, chief justice of Baltimore’s criminal court, arrived on the scene. A loyal Republican, he did little to subdue the crowd. The responsibility for preventing the violence rested with Brigadier-General John Stricker, commander of the Baltimore Brigade of Maryland’s militia. But he dithered in his home, just doors down on Charles Street. Stricker was also a loyal Republican, a merchant and banker. He had little interest in dispersing a crowd of politically like-minded citizens in order to save a pack of Federalists. Urged by concerned citizens, he did as little as possible, first ordering two justices of the peace to sign a statement enabling him to intervene and then—instead of sending in the entire Baltimore Brigade, the five-thousand-man militia at his disposal—sent Major William B. Barney and a selection of men from his small unit to settle the matter with a mob now numbering over three hundred.

This was barely a half-measure. Barney was a Republican candidate for the House of Delegates, and like Stricker had very little political motivation to forcibly remove the mob. When he arrived with thirty of the ninety troops in his unit, he had orders from Stricker not to fire on the crowd. At 3:00 a.m. Barney moved his men into a line in front of the house, forming a blockade between the attackers and their prey. Soldiers, their swords held aloft, were stationed by the windows. So riled were the throng that Barney was approached by a drunken Irishman who accused him of protecting the Tories and punched him in the chest.

Once he managed to enter the house, Barney conferred with Lee and Hanson. There was little he could do, the major explained. He had not been ordered to disperse the crowd. His men did not even have pistols. When he asked for a drink of water and Lee walked with him to a cupboard to fetch it, Barney pleaded with Lee not to stand near him, lest those outside think they were in league and kill him. “I know your situation, it is a delicate one. I am sure you are doing all you can,” Lee charitably responded.

Once again outside, Barney explained to the crowd that he was there only to secure the property and those in it. Many happily assumed this meant he was there to apprehend and jail Hanson and his comrades. But still they lingered, growing impatient, and eventually breaking into a nearby armory and dragging a cannon to the house. The men, though, didn’t know how to fire or even aim the weapon.

Finally, as the sun began to rise, Baltimore mayor Edward Johnson and General Stricker appeared on the scene. The former, yet another Republican, had been mayor for four years and was in pursuit of a second term in that office. He entered the house and delivered a rebuke to Hanson: his conduct was inviting civil war. But this was his house, and he had every right to defend it, Hanson countered. Ultimately Johnson and Stricker could not and would not protect the party; the only recourse was to surrender to the city’s authorities and be escorted off to jail. There, Stricker promised, they would be safe.

Hanson vehemently objected to this proposal. “To Jail? For what? Protecting my house and property against a mob who assailed both for three hours,” he cried. Lee inquired why the entire Baltimore Brigade had not been called out. That is the brigade, said Stricker, pointing to the crowd outside.

Lee, many years Hanson’s senior and no longer the quarrelsome young soldier who had beheaded deserters and challenged Congressmen to duels, recognized the odds. Supplies were dwindling; there was little food or water left in the house. Only twenty-three of the defenders remained; the rest had escaped during the night. Every single authority in the city, Jeffersonians all, was predisposed towards the mob. If another confrontation came, the men in the house would have little chance of survival.

Surrender was the only chance to end the stand-off without further violence. Lee parleyed in the home’s parlor with Johnson and Striker for terms of surrender. Could they be allowed to leave the home bearing their arms, on horseback, surrounded by the militia? This was not permissible, replied Johnson and Stricker.

Hanson protested bitterly. The promises of these Democratic-Republicans could not be trusted. If they could not dismiss the mob, they could offer no real protection. He repeated over and over that to surrender was to be sacrificed. But eventually Lee convinced Hanson and the others to submit. He believed that the assurances from Stricker, a fellow veteran of the Revolution, that the party would be protected, were trustworthy. At 9:00 a.m. the party exited the house, marching a mile to their destination in a protective square formed by militiamen. The home was ransacked shortly after its inhabitants departed.

Upon hearing of an unexecuted plot to stone the prisoners to death on their way, Johnson and Stricker ordered a brigade of militia to guard the Baltimore City Jail, a two-story stone structure with no perimeter wall. But these militia would be furnished only with blank cartridges. Rightly fearing they would be torn to shreds by a bloodthirsty mob, barely fifty soldiers appeared at the militia headquarters on Gay Street.

After their hour-long journey to the jail, during which they were pelted with rocks, Lee and the others were crammed into a barely finished room, off a long corridor sided by cells in a section of the building reserved for “negroes and rogues.” A stout door secured the prisoners, its thick iron bars forming a grate.

In the afternoon both Johnson and Stricker arrived at the jail, along with other city officials, to guarantee prisoners would be safe. But two leaders of the mob slipped in behind the mayor’s party and carefully studied the faces and clothing of the prisoners.

As the city leaders left the jail, they encountered a gathering crowd outside. When promises were proffered that no bail would be posted for the prisoners, the gathering seemed to disperse. Satisfied, Stricker rode home, intent on finally catching some sleep. On his way he dismissed the militia. Lee’s trust in a fellow warrior was badly misplaced; he later cursed the “base perfidy of General Stickler’s un-kept promise of protection.”

Word that the militia had been recalled filtered back towards the jail. The mob, construing this as tacit approval of a massacre, regrouped and stormed the building. When the entrance to the jail would not give, they moved around to an opening on the east side of the building. Now three doors separated them from their prey. The first, they labored to take down for fifteen minutes before finally passing through. The second door they bashed open quickly. The mob then entered the corridor in search of Lee and Hanson’s cell. Initially they hit on the wrong room, but a Frenchmen inside pointed them towards the right one.

Watching the scene unfold through the spaces between the iron bars of their door, the prisoners hurriedly debated a course of action. Armed with only a handful of pistols and daggers, they wouldn’t be able to fight off the mob. Lee suggested they use the pistols to kill themselves, sparing themselves from the coming torture and depriving the would-be murders of the pleasure.

John Thompson, one of the youngest and strongest of the prisoners, welcomed the fight. As the mob searched for the cell, he shouted, “You are at the wrong door, we are in here!” When they arrived at the right door, they opened it with its key, likely procured by the butcher Mummua, one of the men who had scoped out the prisoners when Johnson and Stricker visited the jail. At that point Thompson, along with Daniel Murray, burst out, pistols pointed forward, warning, “My lads you had better retire, we shall shoot some of you.” Members of the mob replied, “How will you do it, you can’t kill all of us!” Then in an instant Thompson and Murray sprang forward, extinguishing the torches of their unwanted visitors, sprinting towards the jail’s front door.

In the ensuing darkness and confusion, the prisoners proceeded out the door of their room, rushing for safety. Thompson was the first to pass the door, but as he exited he was bashed on the head, and tumbled twelve feet down the stairs leading out of the jail. Surrounded, he begged for his life, only to be tarred and feathered and then put in a cart and wheeled away, his face slashed with rusty swords. John Hall and George Winchester were also beaten on their way to freedom. In minutes the jail’s floor had turned red with blood.

As Hanson made his dash for the door, Mummua recognized the arch-Federalist, knocked him senseless, and tossed his limp body down the stairs. When the crowd beat the crusty old Lingan, he chided his attackers. He had fought for their freedoms, after all. In his last moments he ripped off his clothing, exposing the scars he still carried from the war. Where had his attackers been during the Revolution, “in France or among the bogs in Ireland”? As he was bludgeoned to death, a member of the mob declared that “the dammed old rascal is the hardest dying of them all!”

This was not technically true. As Lee made his way from the cell, he was apprehended, his head pummeled with clubs, his body hurled outside, bounding down the steps before finally coming to a rest atop the shoulders of a John Hall. The bodies of others were quickly piled on top of those two, forming a macabre monument to the throng's bloodlust.

Lying on the ground, unable to move, Lee quietly groaned. This only excited the crowd. As more men arrived, he was singled out as “the dammed old tory.” One of them snorted, “He died true game—huzzaing for King George to the last,” seemingly unaware that the mob’s victim had long ago helped pry that monarch’s grip off of America

An assailant approached Lee’s wounded body, drew back his blade and began to slice off his nose. Unable to severe the entire thing, he left Lee with a gaping gash in the middle of his face. Now another knife was thrust at his eye; just as it reached his face, Lee sat up, blocking the blow, which instead ripped through his cheek, covering his weathered face in blood. He collapsed, his head falling on the prostrate Hanson’s breast. He was promptly kicked off, leaving a crimson splotch on the younger man’s chest. “See Hanson’s brains on his breast!” enthused one of the monsters, mistaking Lee’s blood for Hanson’s. To measure if any life remained, Lee’s eyelids were peeled open and scalding candle wax dripped over his pupils.

Lingan was dead; Lee, seemingly so. Others, such as Hanson, feigned death. As he lay still, a member of the throng booted him square in the genitals. There were women present too; they chortled at the violence, crying “kill the Tories!” The scene only grew more ghoulish. Children clapped and skipped, and all present joined hands, dancing around the heap of writhing bodies, singing, “We’ll feather and tar every damn British Tory. And this is the way for American glory!” Tributes to Madison and Jefferson followed.

Then came the exciting matter of disposing of the bodies. One voice suggested dumping them in the jail sink. Another suggested tar and feathers. Another advocated for dissection. A mass hanging was proposed. While the debate went on, Richard Page, the prison’s primary physician, alerted to the chaos, arrived. Though a Democratic-Republican, he was appalled by the carnage. He appealed to the mob, worn out from their evening of gory mischief, to go home and leave the bodies under his care. After all, he reasoned, most were dead and the rest would soon be. Satisfied, they merrily moved on. As Page spirited the prisoners back to their jail cell, one spectator asked where they were being taken. To which another responded, “To Hell.”

With the assistance of the jail’s other resident physicians, Page cared for the survivors, dressed their wounds, and provided brandy. An attempt was even made to sew the detached flesh of Lee’s nose back into alignment. The doctor then plotted to remove the wounded from the jail. Carriages were called for; Hanson snuck off and away from the city; others were conveyed into the country in carts covered in hay.

Lee’s mutilated body was slipped off to the city hospital, where the doctors did what little they could to ease his agony. The following morning he was taken to the home of a Federalist safely away from Baltimore, in York, Pennsylvania. There he lay motionless and speechless, attended by a duo of doctors. His head, crushed with clubs, had swollen and turned black. His face was sliced like a roast. A bloodstained flannel shirt covered his body. The rest of his clothes were ripped to shreds and similarly stained, from “tip to toe.” There appeared to be a hole where once of his eyes had once been. When James C. Boyd came to see what was left of Lee, he observed that “when he attempts to stir, he tottered like an infant just commencing to walk.”

National newspapers reported his demise. “Two Great men and heroes have fallen in Maryland! Generals Lingan and Lee are no more! Their spirits have ascended on high!” exclaimed the Maryland Gazette.

In Washington, D.C., the National Intelligencer reported that the mob had “dangerously wounded several, of whom one (Gen. Henry Lee, of Virginia) has since died of his wounds.”

In the partisan press, the past three decades of trouble were sheered away—the notorious business dealings, the humiliating stint in debtor’s prison all forgotten. In death, Lee and Lingan were Federalist martyrs, convenient symbols of Republican savagery. The Baltimore riots were described as “a scene that has never been paralleled since the days or Robespierre.” Lee was remembered in glorious terms, as “the celebrated orator, who, selected by the united voice of his country, delivered the funeral oration over the body of the great, the illustrious Washington.”

His final moments, according to Evening Post from New York, were nobly spent “invoking the spirit of Washington, his friend and companion in arms.”

Federalists gleefully pointed to the grotesque sacrifice of two old war heroes, Lee and Lingan. Indeed, in coming to Hanson’s side, Lee had defended the very rights for which he had fought during the Revolution. And had paid dearly for it. He was no wild partisan; he had come to defend Hanson’s right to exercise his views, not to endorse them. He opposed this new war, but he would have fought in it had he been called to. It was another cruel twist in a luckless life.

Only Lee was not dead. The papers were wrong. Confusion spread. From Stratford Hall, Henry Lee IV wrote to William Williams, the son of one of his father’s old brothers in arms, Otho Holland Williams. He did not know whether his father still lived, he said, he had only heard rumors; what was true? He begged Williams, a Baltimore resident, to all in his power to save Lee’s life.

This was not necessary. A week after the attack, Lee began to speak again, though with difficulty. His family received word that Lee had survived.

“My father was much hurt,” Lucy Lee Carter wept to her aunt, Alice Lee Shippen, informing her of the tragedy in August. “Yes I have heard of the sad catastrophe of Baltimore,” Alice responded a month later from Philadelphia. “How melancholy to think or to write of. It is pleasant to report that the worst is over and he is out of danger.”

Following weeks of recuperation, Lee was well enough to return to Alexandria in early October. But though he had survived the Baltimore mob, he would never recover from their beating.

Lee is recalled by history for his valor during the Revolution, and for eulogizing George Washington as “first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Between and after those summits were valleys of considerable depth – the loss of his first wife, Matilda Lee, bankruptcy and a spell in debtors prison. His health wrecked by the beating in Baltimore, Lee’s last years were spent hobbling around Alexandria, Virginia, his disfigured face covered in bandages. The one-time hero was transformed into a frightening apparition. His final years spent wandering the West Indies, he died in destitution off the coast of Georgia in 1818.

The Baltimore riot, grizzly as it was, is a significant part of Lee’s legacy. He sacrificed his health, and ultimately life, for Hanson’s newspaper, for the right of Americans to criticize their leaders, for the freedom of the press.

Lee shot to fame fighting to guarantee those rights during the Revolution. Fittingly his last great public act, the one that sped his demise, was defending them in Baltimore.